Media | Articles

“We never thought you’d make it!” Remembering Norman Dewis’ overnight race against the clock

The sun’s still a distant dream, there’s low mist, and you’re just off the boat. Ostend, Belgium, seems many miles away from home in Britain, but your final destination in Switzerland is further still. You’re in the most exciting car to have been launched in a generation and the press and public can’t get enough. You can’t stop. You need to be in Geneva as soon as is physically possible, and though you haven’t slept there’s no way out of this impossible journey. Time to put your foot down.

On March 15, 1961, Norman Dewis took a phone call that, in its abruptness, was nothing out of the ordinary in his line of work. As Jaguar’s test and development engineer, it wasn’t unusual for him to be summoned to impromptu management meetings, provide updates on the progress of projects, or drop everything and take to a test track to diagnose an issue his colleagues needed help solving. This phone call was different: Report back to the factory immediately; explanation to be provided on arrival.

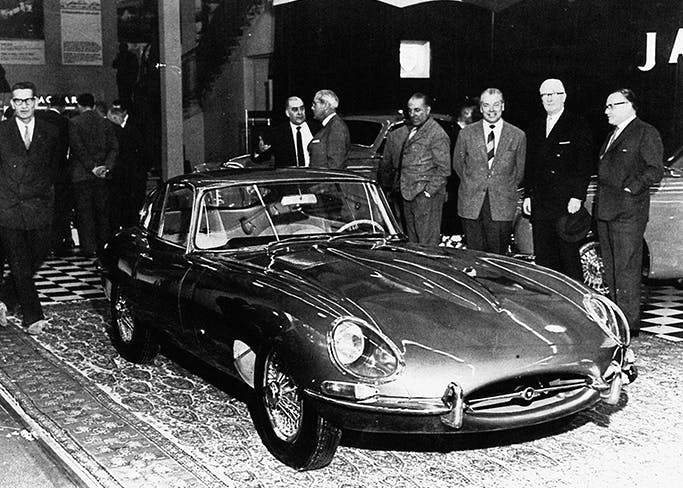

Ahead of the E-Type’s public unveiling at the 1961 Geneva motor show, Bob Berry, Jaguar’s PR manager, had been demonstrating the brand-new model to motoring press. As word spread about the sensational sports car from Britain, Berry was struggling to cope with demand from the world’s media. Sir William Lyons knew that the present rate was unsustainable. He issued an instruction—Dewis had to be there the following morning, with the third car to be built.

Norman Dewis remembered that occasion well. He had been at MIRA testing E-Type chassis number 3, registration 77 RW, and the first roadster to be built, when the phone call came. “I was at the MIRA test track with 77 RW, working on the brakes. The track manager came out, and said they wanted me at Coventry—urgently. I got back about 2:00 p.m. and my boss William Heynes was there with Bob Knight, who had designed the E-Type’s suspension. I asked what was going on, and they said I had to get the car to Geneva as soon as possible.

“I suggested I should go home for a rest while they take out the testing equipment, then pick the car up in the morning, but they said: ‘You go when it’s ready. Here’s a ticket for a 10:00 p.m. ferry at Dover.’ I said I needed to at least grab an overnight bag, but Heynes said: ‘No need. It’s in your office.’ They’d gone and got one from my wife.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

By 7:45 p.m. the car was ready to leave Coventry. The drive to the port, according to Google and thanks to the proliferation of today’s motorway network, is presumed to be 3.5 hours. Dewis had just two and a quarter hours, and A-roads at best for most of the near 200-mile journey.

He made it in two, arriving dockside at 9:45 p.m. having sustained an average speed just below 100 mph. But the gate to the boat had closed 10 minutes earlier, though the boat wasn’t scheduled to depart until 10:00.

“A guy came up with a torch, and I asked: ‘Is that the Ostend boat? Because I have to be on it.’ He said I was too late. Then his torch shone on the green E-Type, and he asked: ‘What’s this?’

“‘It’s the new Jaguar E-Type.’

“‘The one that launched yesterday? It’s all over the newspapers. Hang on.’

“He got his walkie-talkie out and said: ‘You’ve got to get this guy on, he’s got the new Jag.’ While I grabbed a quick coffee and a sandwich, everyone on the boat was looking at it.”

But Dewis couldn’t afford to loaf around once he hit the shores of Belgium’s Ostend. There were still another 500 miles to go, and he was expected in Geneva by 10 a.m. There was little time to waste.

As the mist lifted around Brussels, he was able to push on a little harder, averaging 80 mph through the Black Forest. He looked at the map every half hour or so to get his bearings and made a single stop for fuel. In just 11 hours, with an average speed of 68 mph, he had arrived at Geneva.

“Lyons said I needed to be in Geneva for 10:00 a.m., and when I pulled in, he was waiting,” Dewis recounted. “He walked over, looked at his watch, and just said: ‘Thought you’d do it, Dewis.’ That was about as much of a compliment as you got. He was forthright like that—never one to waste words.

“Then Lofty England, Jaguar’s service manager and race manager, came over and he gave me a big hug. ‘Well done, Norman. Fantastic driving. We worked your speed out, and we never thought you’d make it.’”

Expectant of a good night’s sleep in his hotel, Dewis would be disappointed. England and Lyons informed him that the 77 RW had to be used for demonstration runs immediately, and that Dewis wouldn’t be seeing his hotel until much later in the day.

The thought of experiencing one of those early demonstration drives, given by a sleep-starved racing driver whose history would become so closely intertwined with the Jaguar marque, is enough to send a shiver of excitement down the spine of any car enthusiast. Did any of the press in attendance realize that their driver had been in England with the car barely 12 hours earlier?

Dewis saw it as all part of the job. “None of us ever dreamed of the impact the E-Type would have. And everywhere I go, talking about Jaguar, people ask me about that run. But it’s one of those things—it’s your job, and you get on with it. I really enjoyed that drive, because everything worked out. I had a perfect run from Coventry to Dover, there were no hold-ups in London, I just managed to catch the ferry, and there were no problems in France or Switzerland. I didn’t have one hairy moment—everything went perfectly.”

Jaguar had planned to make 250 examples of the E-Type but, by the end of the Geneva Motor Show, pre-orders topped 500. Over the next 14 years, the company would sell 72,000 units.

Sixty years later, the E-Type’s star still shines brightly. With early cars worth six figures—and 77 RW itself worth whatever anyone cares to name—the story of the £2000 Jag that showed up £4000 Astons and £5000 Ferraris is still one of the most captivating tales told, and the E-Type remains among the most revered cars in the world. Norman Dewis isn’t with us to celebrate 60 years of his incredible feat, having died in June of 2019 at the age of 98, but the account of his drive that night has gone down in history.

Such things simply don’t happen in 2021. Today, such an attempt would cost Dewis his license and his livelihood, not that Jaguar would contemplate even asking such a thing. But the story, the legend of that dash to Geneva against the clock, lives on.