Media | Articles

Was Bill Lear’s steam-powered Vapordyne more than Indy-racer vaporware?

The STP Turbine race cars on display at the inaugural American Speed Festival got me thinking about other alternative powerplants that have been used to go racing. Today we have battery-powered Formula E, and Formula 1 uses hybrid combustion/electric drivetrains. In 1952, the Cummins Diesel Special started the Indy 500 from the pole position, having set a record qualifying speed. There was even an ill-fated attempt by successful inventor and entrepreneur William Lear to power an Indy racer with a steam engine. The car was branded the Vapordyne, and today it’s tempting to call Lear’s idea vaporware. In truth, the Vapordyne project was somewhere between the fraud-filled Dale and Andy Granatelli STP Turbines, which came tantalizingly close to winning at Indy.

Bill Lear was one of America’s most prolific inventors, earning over 120 patents. While he is best known for creating the Lear Jet, the first successful business and private jet airplane, Lear, who was mostly self-taught, was a genuine pioneer in the electronics and aviation industries. Just as the Lear Jet overshadows most of his inventions in general, his development of the 8-track audio tape player tends to obscure his earlier electronic successes. He first invented a “B-battery eliminator”, what today we would call an AC adapter, to substitute for the high-voltage battery cells used in portable vacuum tube based radios, and then sold to Zenith 50,000 miniaturized tuning coils he invented. Working with his friend Elmer Wavering and Howard Gates, an engineer at Zenith, Lear developed what is considered to be the first practical car radio—the basis of the Motorola company. After buying his first private plane in 1931, Lear turned his attention to avionics. He invented a radio direction finder, autopilot systems, and the first fully automatic aircraft landing system. For his early contributions to aviation, he was awarded the Collier Trophy 1949 and after the success of the Lear Jet he was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, the International Air & Space Hall of Fame, and the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Successful as he was, Lear would end up spending a large chunk of his fortune on a quixotic quest to run steam power at the Indianapolis 500.

Today, when we discuss automobiles and the environment, the topic usually centers around carbon emissions and climate change. But when concerns about air pollution first arose in the 1960s, the emphasis was on smog, usually concerning on the haze that hung over the Los Angeles basin. By the late 1960s, the California Air Resources Board and the federal Environmental Protection Agency were encouraging research in alternative forms of propulsion. The Post Office had American Motors make it some battery-powered postal Jeeps and the EPA funded, and then bureaucratically killed, a hybrid Oldsmobile developed by EV pioneer Victor Wouk. Perhaps encouraged by CARB investigating alternate power for transportation, Bill Lear started pursuing the development of a modern steam engine. Why would an air pollution regulator be interested in steam power? Like gas turbines, steam engines can run on a variety of fuels, some of which burn cleaner than gasoline.

Lear had sold his interest in Lear Jet and had at his disposal millions of dollars to pursue whatever interest he chose. Some sources say he was depressed after selling the jet company, possibly suicidal, and that the steam engine project was a way of breaking out of that depression. Whatever the reason for his interest in steam power, having manufactured radios, avionics, and airplanes, Lear knew a bit about mass production and it appears that he had no interest in going into the car making business, notwithstanding incorporating as Lear Motors Corp. Instead Lear wanted to establish the intellectual property, develop the engine into a practical powerplant, and sell the rights to one of the major automakers in Detroit.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Then, in 1968, Bill Lear, a tireless self-promoter if there ever was one, met someone who apparently sold him the proverbial bill of goods: Ken Wallis.

While a historian of steam power calls Wallis a “complete charlatan,” Wallis is widely credited as having designed Granatelli’s groundbreaking 1967 STP Turbine car that Parnelli Jones drove almost to an Indy 500 victory. The following year he worked on Carroll Shelby’s own turbine Indy effort, but Shelby’s chief engineer Phil Remington caught him cheating on the new air inlet regulations implemented after the ’67 STP car so dominated most of that year’s race. Shelby pulled the cars just before the race to avoid the scandal of being disqualified.

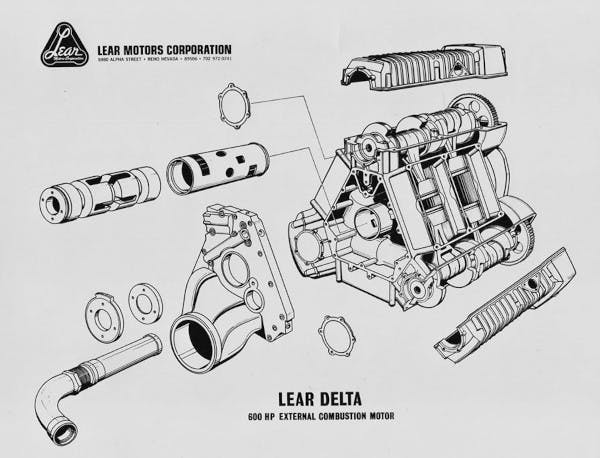

Wallis apparently sold Lear on the idea of making a steam version of the diesel-fueled Napier Deltic engine, a Rube Goldberg (Heath Robinson for our readers in the U.K.) looking opposed piston design with cylinders arranged in a triangle driving three separate crankshafts. Wallis also convinced Lear to promote their new steam engine by entering it in the 1969 Indy 500, just 13 months later. Lear started construction on a replica of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway near the Reno HQ of Lear Motors for testing. You can still see the bulldozed oval when flying overhead.

Here’s the layout of the Napier Deltic engine:

Lear already had an existing R&D team working on steam power and he actually was granted a couple of patents on vapor generation, but he put Wallis, who had no real experience with steam power, in charge of the project. Wallis may not have been the only person in the project stretching the truth. Lear himself claimed to have invented a new fluid he called Learium, that supposedly had ideal thermal conversion properties, better than water, something thought to be only theoretically possible. Later, Lear abandoned Learium, he said, because it wasn’t as chemically inert as he had thought. Learium has caused some critics to conclude that Lear was trying to defy the laws of thermodynamics and physics.

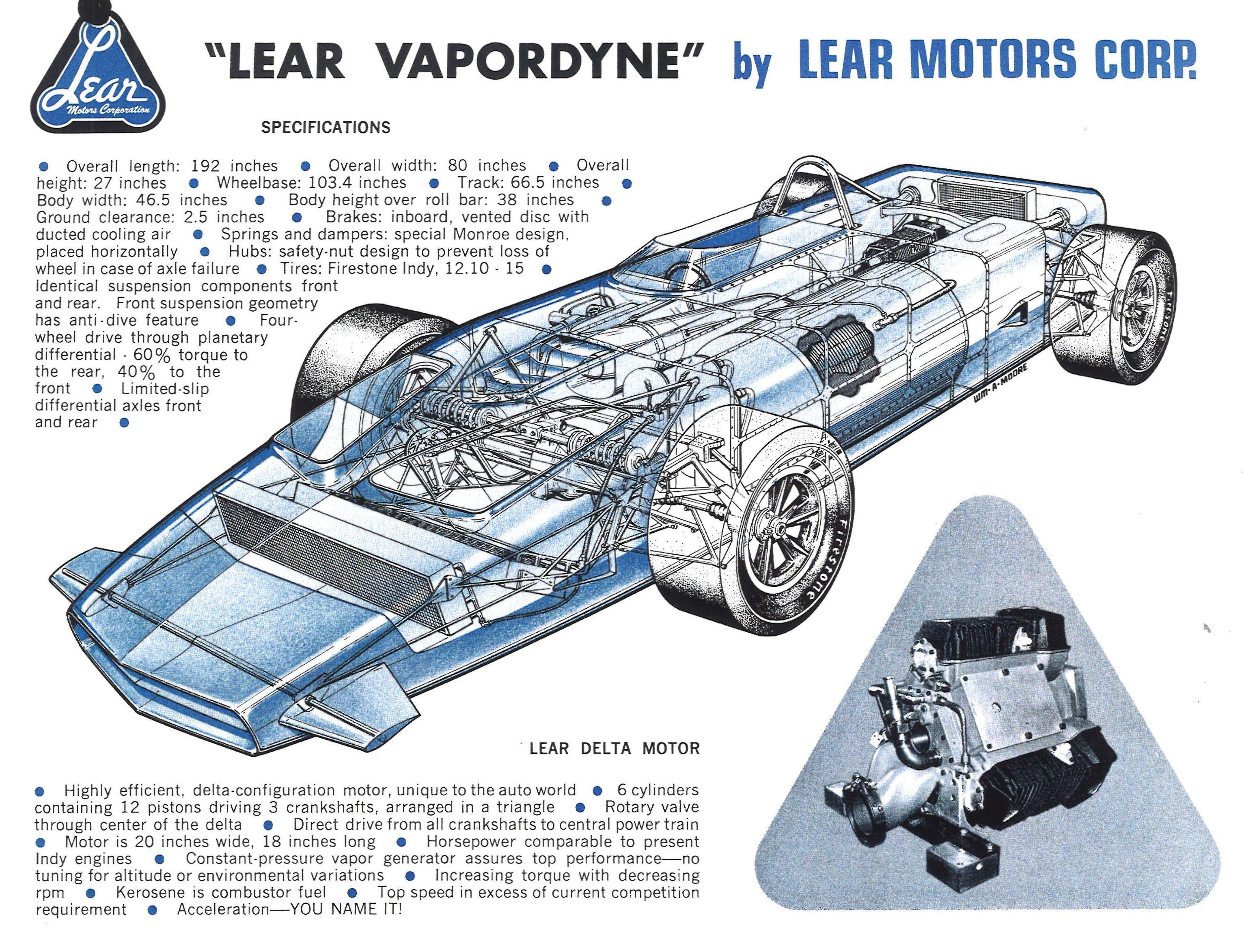

They advertised the new engine as a 20-inch by 18-inch, “Highly efficient, delta-configuration motor, unique to the auto world – 6 cylinders containing 12 pistons driving 3 crankshafts, arranged in a triangle – Rotary valve through the center of the delta.”

The effort was widely publicized in the general press, in automotive publications, and in magazines like Popular Mechanics.

Wallis ended up spending four million dollars of Lear’s money making a four-wheel-drive rolling chassis that looks a lot like the ’67 STP and ’68 Shelby turbine cars, only instead of the turbine sitting next to the driver, the boiler for the steam was located there. The compact engine was supposed to be located behind the driver. According to the April 1969 issue of Road & Track, though, a month before it was supposed to race at Indianapolis no engine had run; the boiler hadn’t even been built. In June of that year Lear fired Wallis.

After spending a reported $13 million or so developing the Vapordyne engine, Lear’s steam team continued to noodle on vapor power, turning from pistons to turbines. They would go on to build at least one demonstration steam-turbine-powered city bus in the early 1970s that apparently worked well enough when tested by municipal authorities in California. It was not very fuel efficient, however, and after the 1973 oil crisis made fuel economy a critical political issue, the project died for good. Sources indicate that the Lear team also built a steam-powered Chevrolet Monte Carlo whose details (and fate) is unknown at this time.

In contrast, the Lear Vapordyne Indy racer does exist—still a rolling chassis—and it belongs to Rick Parsons’ Vintage Indy Racing Group located near Chicago. Parsons raced in Can-Am in the ’80s and has restored the Vapordyne roller. There is no trace as to what happened to Lear’s take on the Deltic engine, if anything other than a mock-up ever actually existed. Clearly Lear was not some get-rich-quick scammer peddling pipe dreams, and serious engineering work was dedicated to developing the Vapordyne. Whether it was doomed from the start or merely a victim of bad timing, this is one ambitious concept that evaporated into history.

we can bring back the steam powerd..

Good story. Good writing.

People should be referring to this Bill Lear, in terms of genius. Similar to an Elon Musk type from today.

I’d like to see an affordable, tractable, rugged steam engine of modern manufacture, somehow. Sized appropriately for powering a sawmill, lawn tractor, go cart or generator. The Stanely Steamer 6 hp engine was a little overbuilt but still; a refined, simple design.

https://cactusbush.wordpress.com/2024/01/15/book-is-here/

Need to contact Lear’s successors to get info on his halogen mixture “Learium”. I have an application. Any ideas on reaching ‘Cava’ (son)?

Turns out Cava is dead but sister Shanda is alive and active. Trying to contact her. Lear archives are at Seattle’s Museum of Flight. A LOT of information there.

Lear had i read sold the patent rights to Learium and the engine concept that he said could operate indipendently of any gas or oil to the gas companies around 1968 for 1 million. Thats why no one has ever gone on to try and develope it. Elon Im sure could if he wanted to though. When you have college students building electric cars that go 650 miles between charges using solar cells to help charge the batteries why hasn,t generators been used to help with this also so charging is no longer a necessity similar to gas cars?