Media | Articles

Volvo’s Heartbeat-Sensing Anti-Carjacking Technology Was Y2K Safety At Its Weirdest

Every once in a while, an automaker debuts a feature that is truly unique, standing apart from everything else on the market. In some cases, these novel technologies serve as the thin end of a wedge that opens up a whole new world of vehicle development, with rivals quickly co-opting and branding their own version of the innovation.

In others, you end up standing in a parking lot in the year 2006, watching “Ray the Burglar” be apprehended by a security system that’s been specifically designed to detect his heartbeat as he hides in the backseat, like some digital combination of Sherlock Holmes and Robocop.

Such was the media introduction given to the most intriguing capability of Volvo’s Personal Car Communicator, a thin slab of plastic that initially served as a super-fob for the flagship S80 sedan. Billed as a bulwark against the threat of kidnappers, carjackers, and bloodthirsty murderers who were apparently lurking around every corner of a Volvo owner’s action-packed existence, the heartbeat sensor was an entirely singular high-tech achievement that no other car company ever came close to implementing in any of their vehicles.

What prompted Volvo, a brand known for sensibility and safety above all else, to infer that its customers were living a lifestyle that required this level of electronic overwatch to keep them from becoming just another statistic on a police blotter? And why didn’t the heartbeat sensor catch on long-term in the industry—or even with Volvo’s modern-day lineup? It turns out that the answers to those questions are tied directly to the times that produced this utterly unusual, and unforgettable, feature.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

From Nuclear Power Plants To Your Sensible Swedish Sedan

A quick primer on how Volvo’s Personal Car Communicator (PCC) managed to see inside a living human being and keep tabs on the heart beating in their chest.

At its core, the setup relied on a vibration sensor originally developed in partnership with Ford (during their brief ownership of the automaker), which was in turn derived from a surveillance system intended for installation at nuclear power plants. The device was so sensitive that it could “listen” for the pounding of the body’s most faithful organ by filtering it through the vehicle’s metallic structure, making it usable even in a noisy outdoor environment or when subject to the booming reverberations found in a parking garage.

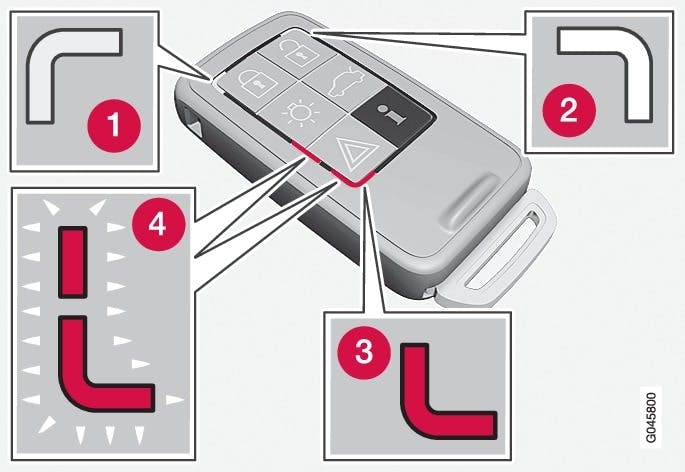

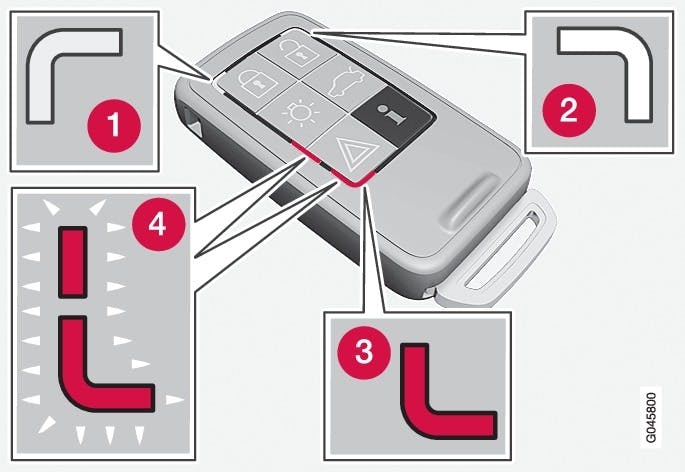

The sensor, which was active whenever the Volvo’s alarm was set, had to be queried by the owner—and that had to be done within a relatively close range of the car itself. From a distance of 100 meters, pushing the PCC’s “information” button put it in communication with the security system. If anyone had broken in, a single red light would appear on the remote. If they were still lurking inside the automobile, a pair of red lights would flash, warning you that maybe it was time to put considerably more distance between you and your would-be assailant.

Everyone Was Getting Jacked In 2004

If all of the above sounds more than a little over the top, you’re not alone. I’ve long been fascinated with why Volvo specifically took a walk down this particularly hardcore personal security path. To find the answer, I got in touch with Thomas Broberg, Engineering Manager at the Volvo Cars Safety Center, who has been with the company for more than 30 years. Not only was Broberg involved with the development of the Personal Car Communicator at the Safety Center way back when, but he also played a personal role in introducing the heartbeat sensor to journalists at a long list of press events.

“I had the privilege from time to time to do demos,” he said, explaining that the feature was eventually expanded to the V70 wagon and the XC70 crossover. He would regularly arm the system and direct “Ray the Burglar,” a Volvo employee unafraid of playing the villain, to trigger the sensor from within the vehicle. “Actually, I ended up doing it a lot. It was something you could show in the parking lot when people were just waiting to get going [behind the wheel]. Poor Ray.”

As it turns out, however, burglary was low on the list of reasons why Volvo developed the feature. To truly understand why the heartbeat sensor was implemented, you have to cast your mind back to the social climate of the early 2000s and, more specifically, what the company’s customer research was telling them about the wants and needs of drivers.

“At that point in time, there was actually quite a lot of emphasis on carjacking as a phenomena,” said Broberg. “Specifically, markets like Brazil and the U.K., where someone trying to steal your car from you while you were at the car itself was a major concern. [Our customers] were feeling unsafe, and unsecure, and that was one of the backgrounds to developing this key. We had a market need and a technical capability that happened to coincide. Why not join them together?”

Broberg certainly isn’t exaggerating about carjacking concerns in the period surrounding 2004, which was when Volvo performed the research that directly informed the PCC’s development. At that time, in the United States alone, roughly 15 murders a year were tied directly to carjacking, and in countries where the threat was even higher—like South Africa—a cottage industry had already sprung up around installing defenses against these violent thefts. Some of these, like “The Blaster” were terrifying, involving flamethrowers that made it hard to say whether they’d do more damage to the vehicle or the would-be ‘jacker.

“It’s like a James Bond type of solution,” said Broberg, referring to these unusual and considerably more violent defenses as compared to the protections offered by the heartbeat sensor.

Technologies Change—But So Do People

If the PCC’s anti-carjacking solution was something customers were asking for, why has it disappeared from the company’s list of available equipment today? And given that there are presumably customers of other, more luxurious brands such as Mercedes-Benz or Bentley who would present high-value targets to cousins of “Ray the Burglar,” how come Volvo was the only automaker to make the heartbeat sensor a reality?

It turns out that the answer to that question has both technological and sociological components, making it more nuanced than one might expect.

“Technology shifts, but I think the need is always there in terms of wanting to feel safe and secure. It’s the means that become different over time,” said Broberg. He went on to explain that while it was sophisticated in the mid-2000s and outperformed other sensors looking for motion or heat detection inside a car’s cabin, looking back now, the heartbeat listening device is crude compared to things like the cameras and LiDAR sensors that form the backbone of modern automotive sensing.

It also had some key limitations.

“As I recall, we discovered that the sensor couldn’t accurately detect a child’s heartbeat, which is more rapid than that of an adult,” said Broberg. “Hypothermia was an issue already on the safety side of things, when children were being accidentally left behind in the back seat. Heat stroke as well.” Since it could only be used as a security tool, this pushed Volvo away from heartbeat detection and towards different solutions that play multiple roles.

There was also the issue of filtering out noise, or ‘scatter’ from the signal in particularly busy environments, not to mention how it performed in various temperature ranges and altitudes. “If you look at the XC90 [SUV] now, we use a totally different technology [to prevent children being left behind],” Broberg said.

Then there’s the fact that how people interact with automobiles—and the world around them—has undergone a dramatic shift, tied primarily to the advantages offered by mobile devices.

“Now, most people have smart phones, which is a totally different means of communication [compared to the PCC],” said Broberg. “You don’t even look at your key anymore. It’s in your bag. Maybe you are even using your phone as a key. And if you are feeling insecure, and you’re alone in a parking garage or somewhere like that and your alarm goes off, we have different behaviors today than we did back then. You probably don’t even approach the car. Instead, you use your phone to call a friend or the police.”

The Thing That Gets You to the Next Thing

Today, there’s no need to ring up the closest nuclear security expert for input on how to keep tabs on a vehicle’s occupants. Technologies like millimeter-wave radar and intelligent video processing algorithms keep cabins covered when it comes to pets and kids, not to mention sentry modes available from dashcams that can commit creeps to video recordings and alert you of their presence long before they nest in your back seat.

Culturally, we’re also much more comfortable, for better or worse, with the prospect of constant surveillance, even inviting technology into our homes that keeps track of our purchasing habits, movements, and the words we say. All of this gets synced up with the device that’s always in our pocket to better advertise to us the products we don’t even know we need yet.

Seen against this backdrop, Volvo’s heartbeat sensor feels invasive only in the sense that it’s actually peering inside our bodies rather than bouncing light or radio signals off of our skin. And by “our,” I mean “Ray the Burglar’s buddies” because the only people exposed to this technology were those bearing ill intent.

Remember: Just because the Personal Car Communicator was pushed aside by the next best thing doesn’t mean that it didn’t make an appreciable impact on the market at large by encouraging both Volvo and its rivals to move on to more effective solutions.

“When we pioneer a technology [at Volvo], if others follow, that’s great, and we will continue to take our next step,” said Broberg. “If others are catching up well, good, I say, because that helps everyone.”

Makes me miss the old Volvo especially for features and ads like this

Sure they were pointless then again just shows how innovative Volvo is and they still innovate to this day

I wish I knew about this in post-pandemic Chicago. I would have rode around fearless …. to some degree.

Interesting read. It’s fascinating to look back on how problems were solved with the technology available at the time. I wonder what current “feature” will be written about 20 years from today under the same theme.

If Volvo was checking for a hearbeat on their current products it would think I flatlined. I use to like Volvo, now I don’t care.