Media | Articles

16 million scooters later, the Vespa’s designer would rather be known for propellors

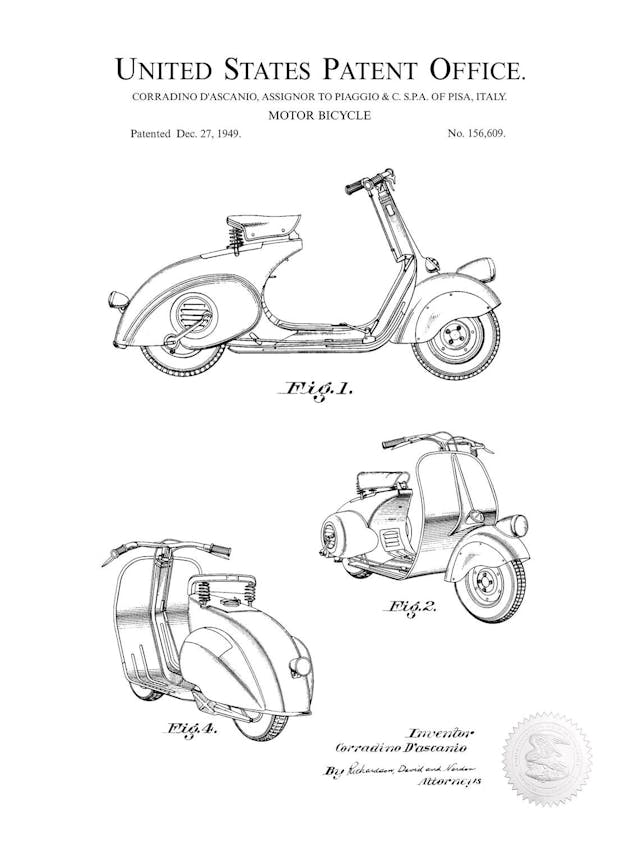

If an engineer or designer created a vehicle that stayed in production for three-quarters of a century, selling millions of units in the process, you could safely assume they’d want such a model to headline their list of accomplishments. We aren’t pulling that example out of thin air, either, because this year marks the 75th birthday of the Vespa, which has sold over 16 million units. In designing this iconic Italian scooter, engineer Corradino D’Ascanio helped create an entire sector of the transportation industry. He had a hand in designing not only the original Vespa but also the first Lambretta motor scooter. Come to think of it, D’Ascanio helped create two transportation sectors; he also designed the three-wheeled Piaggio Ape commercial vehicle, the inspiration for millions of auto-rickshaws on Asian roads.

Surprisingly, though, the Vespa was not D’Ascanio’s proudest achievement. In fact, the little scooter’s success embarrassed him a bit.

D’Ascanio would rather be remembered for his work in aviation, such as designing one of the earliest successful helicopters or developing variable-pitch propellers. However, in many ways his use of aircraft technology was the very thing that made the Vespa such a success.

Inventors generally take pride in their inventions, but the Vespa wasn’t even D’Ascanio’s idea. In fact, he particularly disliked motorcycles, with their grease-flinging, exposed drive-chains and hard-to-change tires. The concept of the Vespa is attributed to industrialist Enrico Piaggio, who commissioned D’Ascanio to work on the little “wasp” and filed a patent for the Vespa on April 25, 1946.

Piaggio’s family’s firm was founded in 1884 to make wooden fittings for the marine industry. In time the company moved into the production of marine vessels and then into aircraft, which is how D’Ascanio ended up at Piaggio in the early 1930s. The Piaggio company eventually supplied Mussolini’s fascist government with military equipment, and D’Ascanio’s contributions to Italian aviation were great enough that he was given the rank of general in the Italian air force.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Following the end of World War II Piaggio was banned from military work and had to find new markets to ensure his company’s survival. Following the example set by Messerschmidt and BMW after the war, firms upon which the Allies placed a similar ban, Piaggio decided to focus on basic motorized transportation.

Ironically, Piaggio’s competitor Ferdinando Innocenti first hired d’Ascanio to design a motor scooter. Italy was devastated after World War II, with little surplus cash and a desperate need for transportation. Though Innocenti and Piaggio are said to have been inspired by the little Cushman scooters air-dropped for American paratroopers during the invasion and occupation of Italy, a number of domestic Italian scooter designs were probably more direct inspirations.

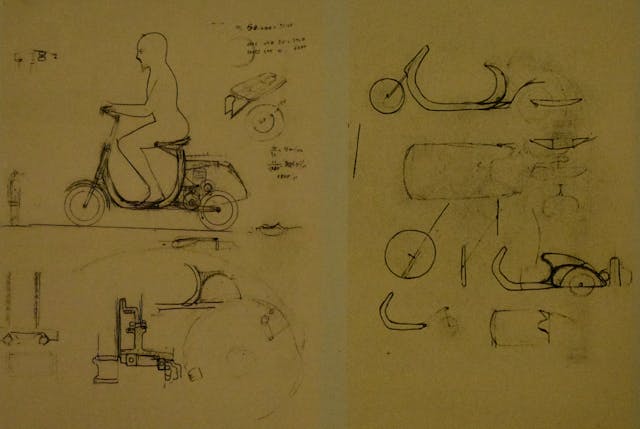

Innocenti’s design brief for D’Ascanio detailed a two-passenger vehicle that had to be reliable and economical. It had to be simple to operate by both men and women. In addition, the cabin-less scooter had to shield its driver (and their clothes) from dust, gravel, and sludge.

Leveraging his background in aircraft design, D’Ascanio drafted a stamped spar-frame that incorporated stressed external steel body panels. Most of the controls, including the gear shifter, were mounted on the handlebars. (For context, consider that contemporary Harley Davidsons had foot-operated “suicide” clutches and hand shifters that required the driver to take their hand off the handlebars.) The scooter’s engine and transmission were mounted directly to the rear wheel, and the whole assembly was suspended on a swing arm, an arrangement that eliminated the dirt-slinging drive-chain and associated maintenance. The front suspension was an aircraft-style trailing-arm, not a telescoping fork. Both front and rear suspensions were “mono-arm,” giving free access to the wheels in case of a puncture. D’Ascanio even included a spare wheel-mounted tire.

D’Ascanio’s revolutionary design was apparently too revolutionary for Innocenti, whose company also produced rolled tubing. Ferdinando wanted to use a tube-based spaceframe, not a unibody. When Enrico Piaggio solicited D’Ascanio to design a scooter, the engineer already had a fully fledged proposal in his back pocket.

D’Ascanio was likely influenced by the 1944 scooter prototype built by Piaggio engineers Renzo Spolti and Vittorio Casini. While its official designation was MP5, for Moto Piaggio #5, it was nicknamed “Paperino,” or Duckling. It had fully enclosed bodywork that was straddled by the rider, handlebar-mounted controls, small-diameter wheels, and a tall splash guard that flowed down from the handlebars and under the rider’s feet. Enrico Piaggio, though, was unhappy with riders having to straddle the scooter. He argued that the arrangement would be troublesome for women wearing skirts or dresses and engaged D’Ascanio to redesign the vehicle. The use of a unibody spar-frame allowed D’Ascanio to outline a stiff structure that allowed a step-through design.

By 1949, the Vespa was popular enough that Piaggio started publishing a magazine. In its premiere issue, Corradino D’Ascanio penned his own account of the Vespa’s creation. Interestingly, he avoids any mention of his work for Innocenti or the Paperino and other early Italian scooter concepts.

“Not knowing motorcycles, I was in an ideal position to create a vehicle without precedents. [Enrico] Piaggio was counting on this. “Only you can tackle the problem with a wholly new outlook,” he told me.

I followed intuitive criteria. I felt that machine should serve those who, like me, had never ridden a motorcycle and hated the machine’s lack of maneuverability. I thought it over for a while and one Sunday the basic idea came to me. The most important factor was being able to mount the vehicle comfortably, something that had already been resolved with the ladies’ bicycle. So I started out with the concept that is fundamental in the ladies’ bicycle. I felt that a seated position was more comfortable and more rational that having to straddle the frame. Then we had to make it as maneuverable as possible. We had to take into consideration its urban use. It had to be ridden without taking one’s hands from the handlebars. How could this be done? Simple, I put the gearshift on the handlebar.

Another thing: it should not dirty hands and trousers, one of the most conspicuous inconveniences with motorcycles. My motorcycle therefore had to have a covered engine isolated from the rider: a single assembly with the rear wheel. As a consequence I created a transmission with no chain, the inline gearbox being incorporated in the engine-wheel assembly.

Another feature was dictated by my aeronautical experience: the mono-strut support for the front wheel rather than the bicycle-derived fork. Moreover, I introduced an innovatory monocoque body, eliminating the tubular system.

In aeronautics there is a dogma among designers: Lightness does not prejudice strength, as long as you do not go too far.

Another requirement, the spare wheel. Remembering that on many occasions, traveling by car, I had seen motorcyclists at the side of the road struggling with a punctured inner tube removed from a wheel, I decided that all-in-all, a mere puncture should not be a problem requiring a mechanic. I wanted my motorcyclist to have something in common with car drivers. In short, I was trying to build the machine as simply as possible.

As the legend goes, when Enrico Piaggio first saw D’Ascanio’s MP6 prototype, with its bulbous rear bodywork connected to the front end via a narrow “waist,” he exclaimed, “Sembra una vespa!” (“It looks like a wasp!”).The name stuck.

The first Vespa was powered by a single-cylinder, two-stroke engine displacing a grand 98cc and producing 3.2 hp at 4500 rpm. It went on sale in 1946 and was an immediate success. Over its lifetime, displacement was increased to 125cc, the headlight was moved from the front fender to the handlebars, and eventually the two-stroke engine was replaced with a more eco-friendly four-stroke. 75 years later, however, the basic design of the Vespa hews closely to D’Ascanio’s original concept.

It’s rare that a product stays on the market for the better part of a century without major redesigns. Sometimes, as with the Zippo lighter and Fender Telecaster, the original design was so well-conceived that it simply doesn’t need any major changes. Corradino D’Ascanio’s Vespa deserves to join that select group.