Media | Articles

Tucker: The man, the machine, the dream

Seventy-five years ago, former car salesman Preston T. Tucker was on the verge of changing the automotive world with a “Car of Tomorrow” that challenged not only Detroit but the U.S. government. We chronicle his rise and rapid downfall, examine his legacy, and celebrate the Tucker motorcars that survive. This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

The summer of 1948 should have been a victory lap for Preston Tucker. The Tucker 48 sedan was finally starting to come off the assembly line at a gigantic former airplane engine factory on the South Side of Chicago. He had been riding a wave of tremendous publicity from an adoring public, who were dazzled by the vision of this singular man to put them behind the wheel of something new and different, a better car than the warmed-over versions of prewar designs that Detroit was peddling. His stock offering had been a tremendous success, 44,000 Americans buying into his dream and helping the Tucker Corporation raise some $15 million in development funds.

Tucker was just getting the taste of that success when, on June 6, 1948, Drew Pearson, a well-connected muckraker in Washington, D.C., told listeners of his widely distributed radio show that the Securities and Exchange Commission had launched an investigation into Preston Tucker and his stock plan that would “blow Tucker higher than a kite.” Four days later, Pearson followed up in his national newspaper column, The Washington Merry-Go-Round, declaring that “the ax is falling on Preston Tucker, the revolutionary automobile man, and falling hard.” The War Assets Administration, Pearson gleefully wrote, had denied Tucker’s bid to purchase a steel factory in Cleveland, which the automaker desperately needed to provide sheetmetal for its cars, and that Tucker the man and Tucker the company were also being investigated by the FBI, the SEC, and a U.S. Senate committee.

This was the beginning of the end of the Tucker Corporation, which had been formed only two years earlier, but Preston Tucker, ever the optimist, went on the offensive, continuing to advertise the impending mass production of “the Car of Tomorrow—Today!”

It was not to be. Only 51 cars were produced. Tucker, rather than overthrowing the automotive establishment, became the cautionary tale—worse, a footnote—of what happens to those who try.

But he was clearly onto something. Seventy-five years later, 47 of his 51 cars remain, including car No. 50, photographed here. Looking back, we can now see that the Tucker legend is as much about Preston Tucker the man as it is about Tucker the car.

***

Born in rural Michigan in 1903, Preston Thomas Tucker was fascinated with the emerging world of cars and spent much of his childhood hanging around service stations and garages. He was, for a brief stint, an office boy at Cadillac. After graduating from Detroit’s Cass Technical High School (which would later produce another automotive upstart, John DeLorean), he spent his 20s bouncing from job to job, including as a police officer for the Detroit suburb of Lincoln Park. Like so many young men in Detroit at the time, he served on an assembly line, at Ford. But at the age of 22, he landed on his innate skill: selling. First in Detroit and then in Memphis, he hawked Studebakers and Chryslers using on-the-street methods such as setting up a fleet of cars and collaring passersby with sales pitches. By his late 20s, he was a zone manager for Pierce-Arrow in Buffalo, New York.

Later he moved his family to Indianapolis for a job with Packard. Tucker began hanging out at Indianapolis Motor Speedway with Harry Miller, whom he’d known for years. Miller had transformed the Speedway with a series of brilliant, all-conquering engines, but he was not much of a businessman. Tucker’s natural salesmanship and promotional acumen complemented Miller’s engineering skills, and by 1931, when the two floated the idea of a four-wheel-drive race car for Indy, news reports referred to Preston Tucker as Miller’s manager.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The relationship continued to flourish, and the pair even flirted with the notion of taking over Marmon, an Indianapolis-based carmaker that was on the verge of bankruptcy. (A Marmon Wasp won the first Indianapolis 500 race in 1911.) In 1935, Miller and Tucker formed their own company, Miller-Tucker, and Tucker persuaded Henry Ford himself to fund the development of 10 race cars for the 1935 season. The project was a disaster, with Tucker’s initial budget of $25,000 ballooning to $117,000. Only four cars qualified and all DNF’d in the race. The failure was serious enough to cause Henry to forswear racing sponsorship for the rest of his life. For Preston Tucker, it was merely a bump in the road, but the long-standing relationship with the highly regarded Henry Miller was a crucial pedigree for his future endeavors.

By the late 1930s, Tucker and his wife, Vera, had settled in Ypsilanti, Michigan, not far from Detroit, where he established Ypsilanti Machine and Tool. These were comfortable and productive years, the family living in a splendid house on Park Street, with a two-story garage behind that was “bustling with draftsmen,” mechanics, and engineers, according to one report. From this successful but modest base, Preston T. Tucker launched multiple entrepreneurial efforts to help with the war effort, including a rear-engine aircraft, a gun turret for B-17 bombers, and a high-speed combat vehicle. None made it beyond the prototype stage, but his ideas received fair hearings from various branches of the government.

As the war was ending, Tucker hoped to become a carmaker, capitalizing on his visceral understanding of car buyers plus the technical knowledge he had gained in the racing world. A less ambitious man might have been deterred by his lack of money, education, or experience in the auto industry. That industry, by 1948, had firmly evolved into an all-powerful Big Three of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, and a few secondary players like Packard and Studebaker, with little room for newcomers. But Preston Tucker would not be thwarted by such conventional concerns.

***

It is worth pausing here to reflect on the scale of Tucker’s ambition. Since Tucker, the only significant new attempts at creating an American automotive brand have been by John Z. DeLorean in the 1970s and, more recently, Elon Musk with Tesla.

Then, as now, it was nearly impossible to start a new automaker from scratch. It simply takes too much start-up capital, not to mention the right combination of brand, marketing, engineering prowess, manufacturing might, and, quite frankly, an undefinable coherence with the zeitgeist.

Musk managed to succeed where Tucker did not. But even Elon recognizes how unlikely that success is and what it can take. When I interviewed him in 2012, as the Model S was just hitting the market, he emphasized the dough he had already burned through. “It’s an extremely capital-intensive industry,” he said. “So, unless [you] have some compelling non-monetary reason to create a car company, as I did, then this is not a good use of capital.”

Tucker ultimately lacked for cash. But non-monetary motivation? He had that in droves.

***

Preston Tucker, like Elon Musk, had no desire to build just a car. He would conceive and construct one that, in his words, “opens a new era in motoring”—a comfortable, efficient, safe, and affordable sedan with technological leaps in suspension, body engineering, and powertrain efficiency.

Tucker brought on George Lawson, an experienced Buick designer, to draw up a sleek sedan. One of the signature elements was to be fenders that turned with the front wheels of the car to illuminate the way through corners. Lawson made a quarter-scale clay model, which was photographed against a background to look realistic enough to be full-size. With photos and drawings in hand, Tucker began his publicity campaign, cozying up to a sympathetic automotive journalist named Charles T. Pearson, who sold an article about Tucker and his proposed car, known as the Tucker Torpedo, to multiple magazines.

Tucker had correctly assessed the mood of the American public—they were starved for new cars after the wartime production shutdown. Throughout 1946, word spread across America of the impending “Car of Tomorrow—Today!” It would feature disc brakes, independent suspension, streamlined styling, and, most notably, a center headlight. And the engine would be in the rear, mated with a new “hydraulic fluid drive” transmission with a torque converter at each rear wheel.

That was the easy part. Raising the capital to manufacture at scale would be a much bigger task. Floyd D. Cerf, a Chicago financier, was enlisted to handle the stock prospectus. “Preston, you are selling yourself,” Cerf advised Tucker. “But we also need a car and a plant.”

Tucker Corporation was officially founded on July 8, 1946. The federal government was sitting on a plant it had built in Chicago for Dodge to build B-29 bomber engines. Now idled, the plant, with its tool shop, foundries, and forging facilities, was ideally located, with ready access to a workforce and close enough to Detroit to tap industry suppliers. The War Assets Administration agreed to lease the plant to the smooth-talking Tucker at favorable terms, with only $25,000 down.

Cerf would seek $20 million in investment as soon as Tucker had a prototype in hand, so speed was of the essence. Alex Tremulis, former styling chief of Auburn Cord Duesenberg, refined the Lawson drawings into a more production-ready design. He also convinced Tucker that the steerable front fenders were unsafe. Tucker gave him 60 days to come up with a prototype, a near impossibility, but Tremulis and his team built one in metal straight from his drawings in 100 days, using the chassis of a junkyard Oldsmobile (there was no time to sculpt a full-size clay model).

An air-cooled, six-cylinder horizontally opposed engine displacing 589 cubic inches, based on each cylinder having a bore and stroke of 5 inches by 5 inches, was cobbled together and installed, with great difficulty, at the rear of the prototype. Tucker claimed the 589’s massive dimensions were recommended to him by Harry Miller when the engine designer was on his deathbed. Whether that truly reflected Miller’s final wishes or Tucker’s love of a great pitch is hard to parse.

The prototype, which became known as the Tin Goose, was unveiled to the public at the Chicago factory on June 19, 1947. The car was rough, with body panels that required hundreds of pounds of lead solder. The front bumper was made of wood, painted black, with metal inlays to give the appearance of chrome. The engine could not easily be started, and the presentation was delayed to the point that the crowd grew restless. Finally, four gowned models sounded a trumpet fanfare, and the curtains were drawn to reveal the Tin Goose.

The crowd went wild. Sure, the car wasn’t ready for the road, but it was real, and it was stunning and looked like no other car of the period. Tucker’s break-neck pace in developing the car was essential to getting distributors and dealers to sign up and investors to write checks.

Not that the SEC, which had issued strong cautions about the unknown company, wanted to make it easy for Tucker or investors. But at no time was Tucker trying to understate the challenges that his fledgling company still faced before mass production could be achieved. “Though the SEC seemed to think its negativity was a necessary counterbalance, the Tucker Corporation’s own assessment was hardly starry-eyed,” wrote Steve Lehto in his superb 2016 book, Preston Tucker and His Battle to Build the Car of Tomorrow. As Lehto relates in detail, Tucker’s prospectus makes clear the “risks and difficulties” in the company’s plans to make a “radically different” car.

The stock prospectus also laid out the technical details of the car: It was to be a four-door, six-passenger vehicle weighing about 3000 pounds, with a 128-inch wheelbase and a selling price of between $1800 and $2000. It would have a 24-volt electrical system rather than the standard 6-volt. Further, the rear-mounted engine would be easily replaced in service, rather than repaired. The prospectus concluded, realistically, with the warning that “Some of the major features representing departures from the conventional automobile have not been tested sufficiently to demonstrate their performance characteristics.”

At the time of the stock offering, Tucker already had 49 distributors and 363 dealerships in the United States, with plans for 100 distributors and 2000 dealerships within two years. By June 1947, the company already had 725 employees.

Preston Tucker decided to take the Tin Goose on a promotional tour to drum up interest in stock sales. This was a delicate balancing act: trotting out a rough prototype (which had to be flown or trucked everywhere) in hotel ballrooms, fairs, and other venues, in a sort of traveling circus—all while engineers, designers, fabricators, and draftsmen frantically developed an actual car back in Chicago. But the roadshow was crucial for implanting the seeds of desire in American consumers. In August 1947, New York’s Museum of Science and Industry displayed the Tin Goose, and as many as 15,000 people per day paid 48 cents to view the Car of Tomorrow. Among the visitors was a man named Carmine Coppola, whose son Francis was with him.

Back in Chicago, a young designer named Philip Egan went to work on interior drawings and concepts. Tucker wanted to emphasize safety. Some of his ideas were, to modern eyes, quite zany: He demanded a “safety compartment” under the dash so a passenger could dive into it in the event of a crash. Yet other features, such as a pop-out windshield, a padded dash, and simple controls within arm’s reach of the driver, were groundbreaking and innovative. There was no time to design and develop a custom steering wheel, but a batch of Lincoln Zephyr steering wheels were sourced from a friend at Ford Motor Company. Seat belts were considered but rejected because it was decided that their mere presence could telegraph to buyers that the car was not safe.

Meanwhile, the 589 engine, despite its enormous displacement, made only 83 horsepower, and its hydraulically actuated valves were not ready for prime time. Preston Tucker set up a skunkworks engineering team back at Ypsilanti Machine and Tool. Among the crew was Preston Tucker Jr., then an engineering student at the nearby University of Michigan. Tucker gave them 90 days to come up with a powertrain, then as now a ridiculously short time frame but a common theme at the Tucker Corporation.

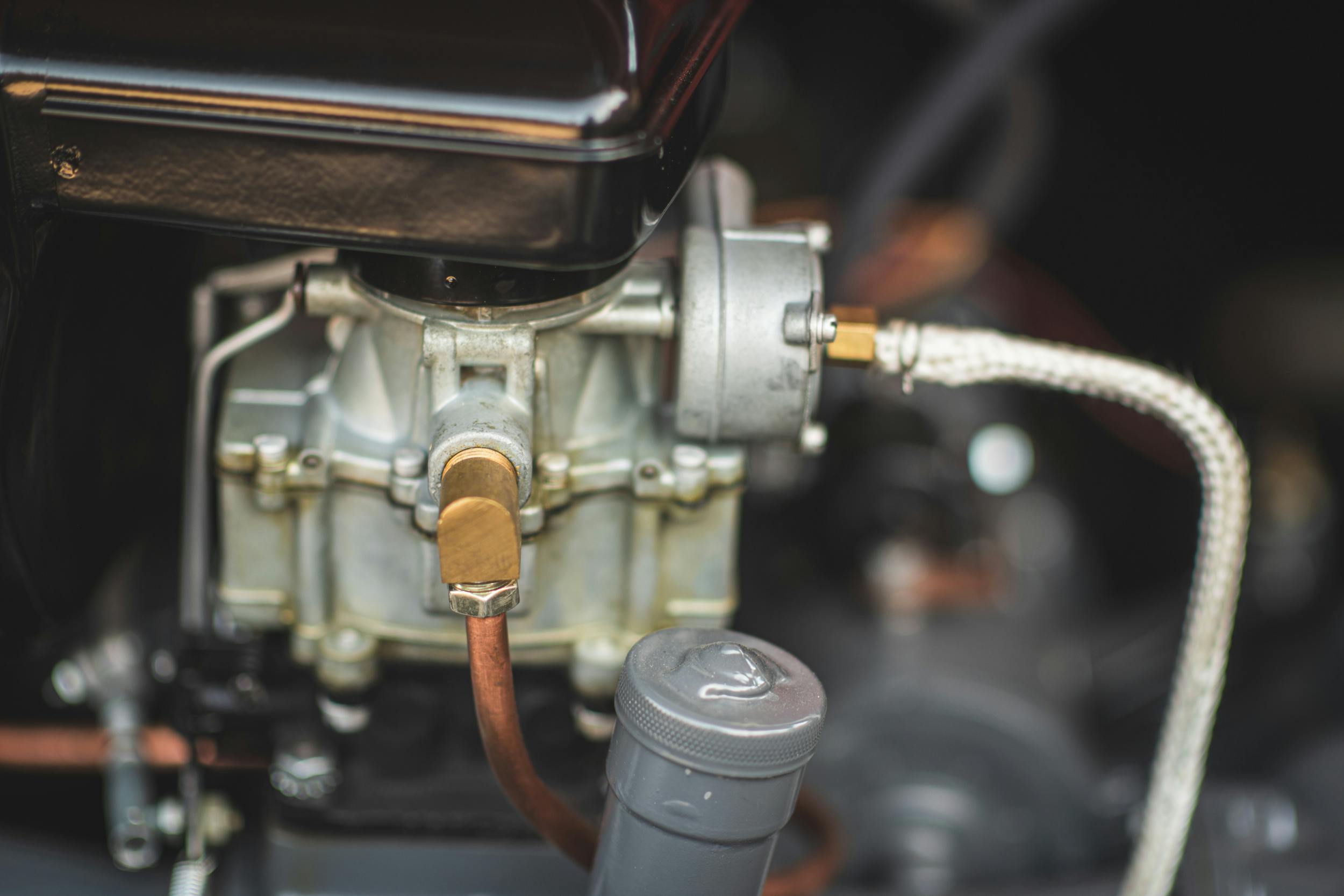

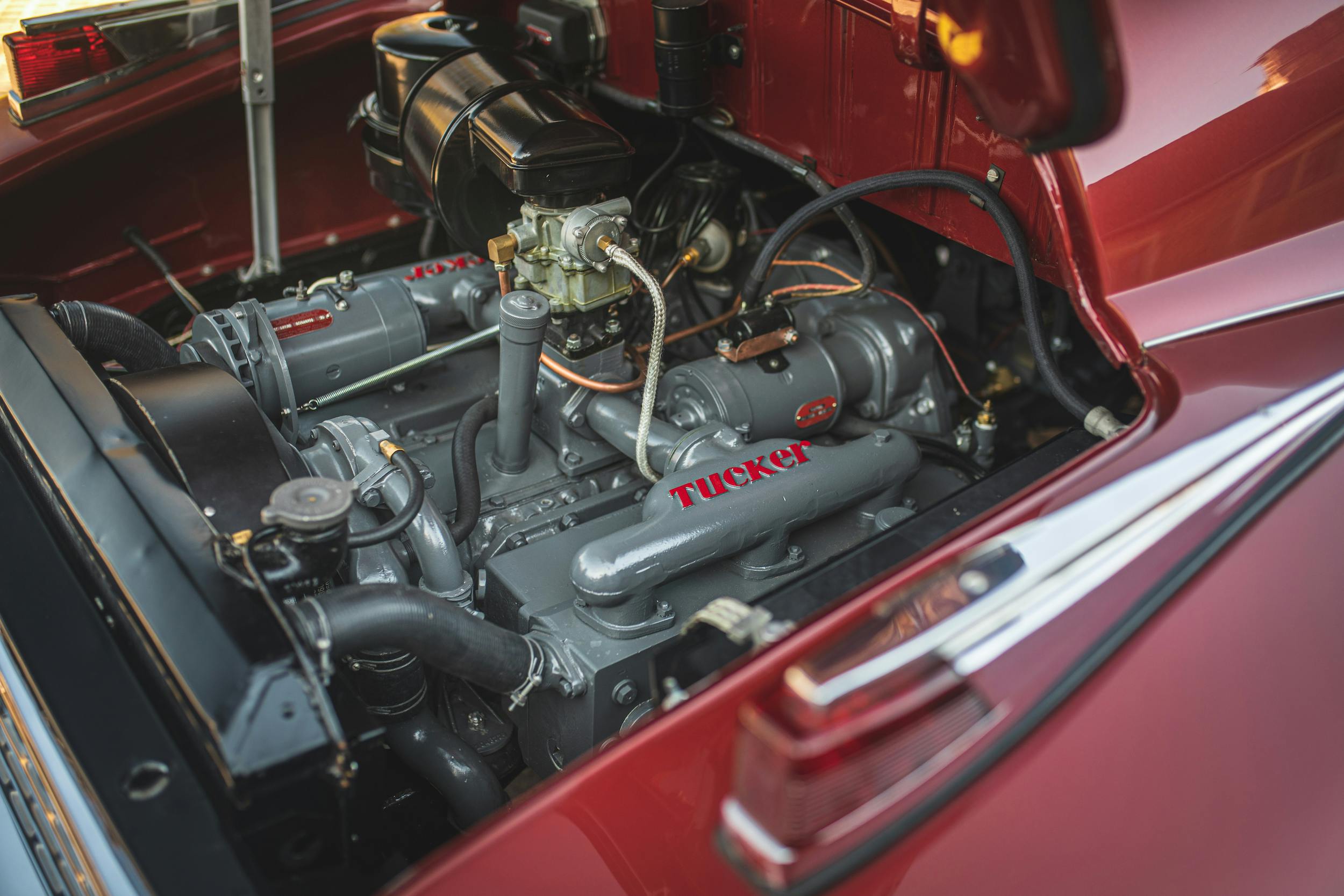

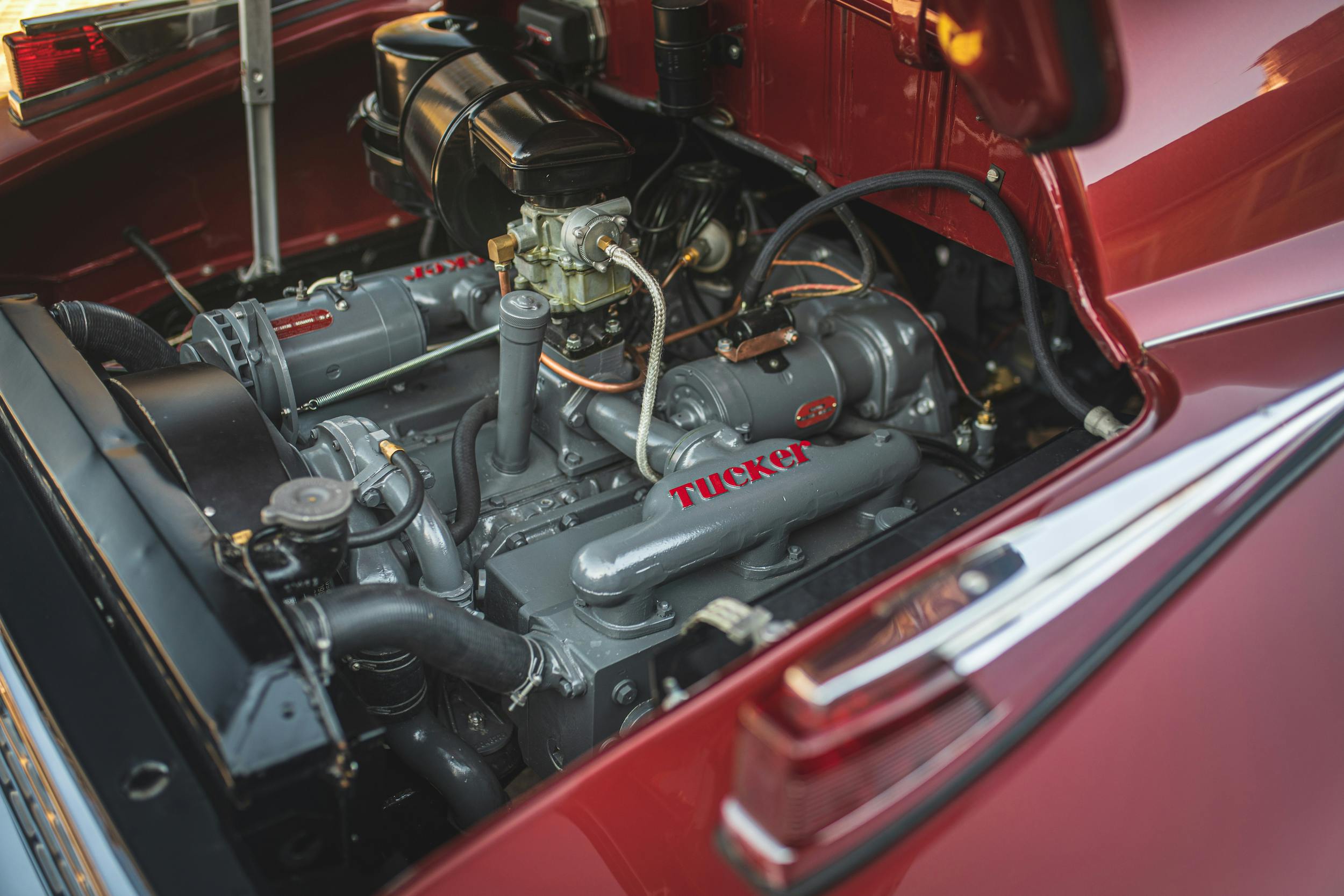

The team evaluated various engine manufacturers, seeking a boxer six-cylinder, and eventually chose a helicopter engine made by Aircooled Motors, formerly Bell Aircraft, of New York. It was known as the Franklin engine, after H.H. Franklin, who had developed a car with an air-cooled engine back in 1902. The crew purchased and tore down four Franklin engines, then rebuilt and re-engineered them for use in the sedan, reconfiguring from air cooling to liquid cooling. Miraculously, the Franklin engine worked so well that the Tucker Corporation purchased Aircooled Motors outright.

There was still the not-insignificant challenge of getting the Franklin’s power to the wheels. The rear location of the engine presented packaging problems for a transmission, and the fluid drive transmission remained more fantasy than reality. The short-term fix was a Cord transmission that had been developed to sit in front of the engine in a front-wheel-drive, front-engine configuration. The team scavenged 22 such Cord gearboxes from junkyards, tore them down, and built 18 transmissions from the parts pile. This was a “pre-selector” gearbox, wherein the driver would operate a delicate lever on the right side of the steering wheel, then depress the clutch, then wait for an orchestra of electromagnets and a vacuum system to shift the gears.

So, with steering wheels from Lincoln, engines from Aircooled Motors, and transmissions from 1930s Cords, the Tucker factory was ready to build its first real car, No. 1001, in time for the first shareholders meeting on March 9, 1948. As with the Tin Goose, the final fittings for No. 1001 came down to the wire, but the mad scramble to develop a powertrain paid off. The Franklin engine produced 166 horsepower and 372 lb-ft of torque.

During this period, dealers and distributors who had signed up with Tucker Corporation were kept abreast of the company’s progress in a series of monthly newsletters called Tucker Topics. These lavishly produced brochures trumpeted Preston Tucker’s executive leadership and the company’s media coverage and made fervent, but often vague, promises about production plans. As noted in the April 1948 issue of Tucker Topics, an assembly line was starting to take shape inside the vast halls of the Chicago factory, and the 52 pieces of stamped sheetmetal required to assemble each car were being positioned. The same issue reprinted an article from the industry trade magazine Automotive News in which the reporter practically genuflected at the altar of Preston Tucker:

“No. 1, of course, is Preston Tucker himself—ebullient, tall, good-looking—he gives the impression of a long knight taking on the giants of the industry. At times he sounds crazy as a loon. After looking over the layout [of the factory], you wonder if maybe he isn’t crazy like a fox.”

Against this backdrop of optimism loomed yet another hurdle: Tucker needed a steady inventory of steel. Fearing that the Detroit makers could easily shut him out of the supply chain, he decided to buy his own steel plant and made a competitive bid for one owned by the War Assets Administration in Granite City, Illinois. Denied that plant, Tucker set his sights on another in Cleveland, which was also being offered by the WAA. Although he was the high bidder, beating out Republic Steel, his bid came to the attention of Senator Homer Ferguson of Michigan, who had previously created obstacles to Tucker getting the Chicago plant and was no friend of the Tucker Corporation. This time, Ferguson went after the WAA itself, accusing it of “gross mismanagement” of government properties. It was clear even then that Ferguson was simply acting to protect the interests of the Detroit Big Three.

On May 28, 1948, the WAA advised Preston Tucker that his bid for the Cleveland facility was “inadequate.” Later, the Cleveland plant would be awarded to Kaiser-Frazer, another fledgling automaker whose co-founder, Henry J. Kaiser, had built Liberty ships for the U.S. Navy. On the same day, Preston Tucker learned that the SEC was launching an investigation into his company.

With time and money running out and a key source of production materiel denied him, Preston T. Tucker was feeling the noose tightening around his neck. Less than two weeks later, the Drew Pearson smear campaign pulled the thread that caused the entire Tucker Corporation tapestry to unravel. Author Lehto succinctly summarized the effect of the negative publicity: “June 6, 1948, marked the end of America’s love affair with Preston Tucker.”

The unraveling was swift. Tucker Corporation stock fell by half, with investors immediately losing some $10 million in value. Banks froze credit, and on June 14, the SEC subpoenaed the Tucker Corporation’s records.

Despite those setbacks, on the factory floor, work continued apace on the first 50 Tucker 48s, and development was underway for an automatic transmission. A prototype called the R-1 was demonstrated to media in Detroit.

With SEC investigators swarming his factory and Ypsilanti Machine and Tool, Tucker went on the offensive, writing an open letter to the automobile industry and publishing it in several national newspapers in mid-June. Without naming Homer Ferguson, Tucker clearly lay the blame at the Michigan senator’s feet:

“Most of the political pressure and investigations we have had to face these last two years can be traced back to one influential individual, who is out to ‘get Tucker.’ If he acts from honest conviction in his efforts to prolong the motorcar shortage and block the introduction of a new and better motorcar, then I hope he will have the courage to tell the public.”

One could view the thinly veiled attack on a powerful senator as foolhardy, or one could view it as the action of a man who was backed into a corner through no malfeasance of his own and who knew that the collective forces of both the American auto industry and its friends in Washington were now fully in league against him. Making his case in the court of public opinion was his last hope to stave off these unwarranted attacks and return to the business of getting the Tucker 48 into production.

There were glimmers of positive media coverage amid that summer’s sea of crushing blows, including an enthusiastic review by the then-dean of auto writers, Tom McCahill. “Tucker is building an automobile! And brother, it’s a real automobile!” McCahill, never one to hold back on the purple prose, effused in the August issue of Mechanix Illustrated. “I want to go on record right here and now as saying that it is the most amazing American car I have seen to date; its performance is out of this world.”

Few would ever experience it. By Thanksgiving 1948, Preston Tucker had idled his plant completely while he looked for a financial savior. Rumors that Howard Hughes was interested in bailing out Tucker were false, but Francis Ford Coppola could not resist a minor Hughes storyline for his 1988 movie, Tucker: The Man and His Dream. Meanwhile, the legal forces being marshaled against Tucker culminated in the announcement on February 14, 1949, that a federal grand jury would begin investigating Tucker.

On June 10, 1949, the grand jury indicted Preston Tucker and seven of his associates on charges of mail fraud, conspiracy, and SEC regulation violations, alleging that the Tucker Corporation had raised $28,000,000 but had spent it all on promotion and building a car while making “false and fraudulent statements.” Tucker, according to the Associated Press, responded, “I have a clear conscience, a marvellous car and the will to fight to success.” He continued, “When this case comes into an open court, I will reveal startling information which will call for an explanation from Detroit and many of our public servants.”

Yet the media piled on, with the influential Collier’s magazine publishing a Tucker takedown on June 25 containing information clearly gleaned from the SEC report, which was supposed to be a sealed document and which Tucker and his attorneys had never seen. Anti-Tucker fever was pitched by the time the federal trial in downtown Chicago began on October 5, 1949. The previous day, a judge had voided the Tucker Corporation’s lease on the Dodge plant. When it rained bad news on Preston Tucker, it poured.

The prosecution called 73 witnesses in a case that dragged on into the new year, but on January 22, 1950, Preston Tucker and the other defendants were found not guilty of all 31 counts. The trial was reenacted in the highest dramatic fashion in the Coppola film, which was highly sympathetic to Preston Tucker, painting him as an automotive David against the Goliaths of Detroit and Washington.

There’s no glossing over the fact that Goliath won. Although Preston Tucker was acquitted of all charges, he was a vanquished man. A bankruptcy court began picking over the remains of the Tucker Corporation, and the physical assets, including the fleet of fully and partially assembled Tucker 48 sedans, were sold at auction in October 1950.

Preston Tucker spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name and floating other automotive production capers, including one in Brazil, but failing health and his lingering reputation scuttled such plans. A heavy smoker, he died of lung cancer in December 1956.

The Tucker factory, which was so huge its kitchen could feed 27,000 people a day, went back to building aircraft engines, under Ford Motor Company, during the Korean War. By 1965, part of the site on Cicero Avenue had been turned into the huge Ford City Mall. Today, the north end of the complex is a Tootsie Roll factory, while the mall, like so many in America, is in decline, with a weedy parking lot encircling a long-closed Sears store.

As for the Tucker cars, Florida hotelier Nick Jenin began collecting them and by 1960 owned a fleet of 10. He took them on tour, charging admission to see “the Fabulous Tuckers.” In the 1970s, a Virginia collector, David Cammack, bought and restored three Tuckers and became a veritable Tucker guru. When he died in 2013, he left his collection of Tucker cars, powertrains, factory blueprints, and other archives to the AACA Museum in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

After the Coppola movie was released in 1988, interest in Tucker cars increased, as did values. (It’s also worth remembering that by this time, upstart Japanese automakers had largely achieved what Tucker had aimed to do four decades earlier—building more innovative cars than the complacent American giants.) Today, Tuckers routinely change hands for more than a million dollars. If you are buying, selling, or restoring a Tucker 48 in modern times, chances are good you’ve crossed paths with Mark Lieberman, a Michigan-based Tucker savant and owner of Nostalgic Motoring Ltd., which specializes in the restoration of Tuckers, Chrysler Turbines, and other low-production treasures. Lieberman has owned six different Tuckers over the years, buying his first, No. 1006, in 1991, which he owned for 15 years. The car photographed here, No. 1050, is his latest and is also the last to be built and the one with the lowest mileage, with only 29 miles on the odometer at the time of our photo shoot in Rochester Hills, Michigan, last November.

“No one had done the research to restore one of these correctly,” Lieberman recalls of his first car. “And although the Tucker movie accelerated interest and value, the Tucker 48 still hadn’t proven to be concours-worthy. I was the first person to restore a Tucker so the concours world and the collector car community would embrace it.” Indeed, a Tucker class appeared at the Pebble Beach Concours in 2018.

Lieberman collaborates with restorer Rob Ida, who was profiled in the November/December 2020 issue of HDC magazine, and Mike and Sean Tucker, twin great-grandsons of Preston, to help interested parties buy, restore, and maintain Tucker 48s. The Tucker twins recall visiting collector David Cammack when they were kids and have drawn heavily on his archival materials to become remanufacturers of Tucker 48 parts such as interior knobs, upholstery, fasteners, weather stripping, hoses, wiring harnesses, and various and sundry other secondary components.

“Our hands-on involvement really started with Tucker No. 44, Howard Kroplick’s car,” Sean Tucker, an industrial engineer, told us. “He loved the fact that the family was involved.” Kroplick bought his Tucker from none other than Lieberman. Stunning in Andante Green paint, it’s known as one of the best Tucker restorations to date and further established that the quartet of the Tucker twins, Lieberman, and Ida is indeed, as Lieberman likes to say, “the Tucker dream team.”

It’s cool when you can engage the knowledgeable great-grandchildren of a carmaker’s founder who, primarily as a passion project to honor their forebear, will ensure your car is as historically accurate as possible. “We’re not millionaires,” Mike and Sean hastened to tell me. “Because [the laborious restoration research] is certainly no way to make a living. Every single one of the cars was different from the others, and we’re very intent on making sure our work is authentic and correct.”

Sean and Mike, whose paternal grandfather, John Tucker, was the youngest of Preston’s five children, are now 42 years old. (Their father, John Jr., was the longtime president of the Tucker Automobile Club of America.) Mike’s three sons, 12, 15, and 18 years of age, “are all very much into what we do,” their father said, and the eldest is being trained in automotive collision at a technical college. If their great-great-grandfather did not live to see his vision vindicated, his heirs are determined to keep the Tucker flame burning. “If you aren’t old enough to have seen the [1988] movie,” Sean said, “the story was kind of dying. We want to get our generation more interested in Tuckers. We want this thing to stay relevant.”

The Tucker Automobile Club of America, in association with the AACA Museum, will celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Tucker 48 the weekend of June 16–18, 2023. The event will draw Tucker family members, Tucker cars and owners, family members of Preston Tucker colleagues, and other marque specialists and enthusiasts to Hershey, Pennsylvania (an easy drive from the NYC, Philly, and Washington metro areas). Of course, there will be a special screening of the Coppola film. See aacamuseum.org for details.

***

Further Reading

Preston Tucker and His Battle to Build the Car of Tomorrow — Steve Lehto

Steve Lehto’s 2016 book is a well-written and comprehensive history of Preston T. Tucker and the short-lived Tucker Corporation. An attorney by trade, Lehto does an especially good job of explaining the months-long legal proceedings that Tucker and his associates endured at the hands of the feds.

Design and Destiny: The Making of the Tucker Automobile — Philip S. Egan

“Preston Tucker was a dreamer; he had courage, conviction and an idea,” Philip Egan penned more than 40 years after he designed the Tucker 48’s interior. Egan was a member of a consulting design firm called Lippincott & Margulies and later was hired directly by Tucker design chief Alex Tremulis. Egan’s account of the frenetic formation and rapid demise of the Tucker Corporation was published in 1989, shortly after the release of the Coppola film.

The Indomitable Tin Goose — Charles T. Pearson

Pearson, the magazine writer whose friendly early articles helped build public awareness of the Tucker motorcar, later served as Tucker’s PR man, and his 1960 book is another fascinating insider’s account. (He is not to be confused with Drew Pearson, the nationally syndicated columnist whose takedown of Preston Tucker was key to the automaker’s demise.)

The website of the Tucker Automobile Club of America has information and photos of each of the Tucker 48 cars, three of which are on permanent display at the AACA Museum.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Speaking of new car start ups: what about Arcimoto?

“Ford Tough”, “Ram Strong”, “Chevy…Like a Rock”, “GMC Professional Grade”! They’re all full of crap!

It’s all about marketing and image. That’s the only way the big 3 sells vehicles.

The picture of Preston holding with Tucker Convertible model with Vera is not legit and has been photoshopped. The real photograph shows him holding the same model, but it is the standard hard top. There never was a convertible, much less a model of one

I am 83 years old, love automobiles. I saw the Tucker movie in 1988 when it came to the theaters, and was impressed with the courage and energy of Mr. Tucker taking on the Big Three automaker monopoly. I am pleased that these interesting cars have been given good care. It is a tribute to him and all of his family. Thank you. JB