Media | Articles

Tri-Motor: When Ford gave the world wings

Every car enthusiast knows that the Tin Lizzie put the world on wheels. Ford sold over 15 million Model Ts between 1908 and 1927, a volume topped only by VW’s Beetle. The 1932 Model 18 successor to the T is equally revered for delivering speed to showrooms. Ford’s new flathead V-8 armed working stiffs with 65 horsepower, enough to middle-finger Chevies and Plymouths of the day.

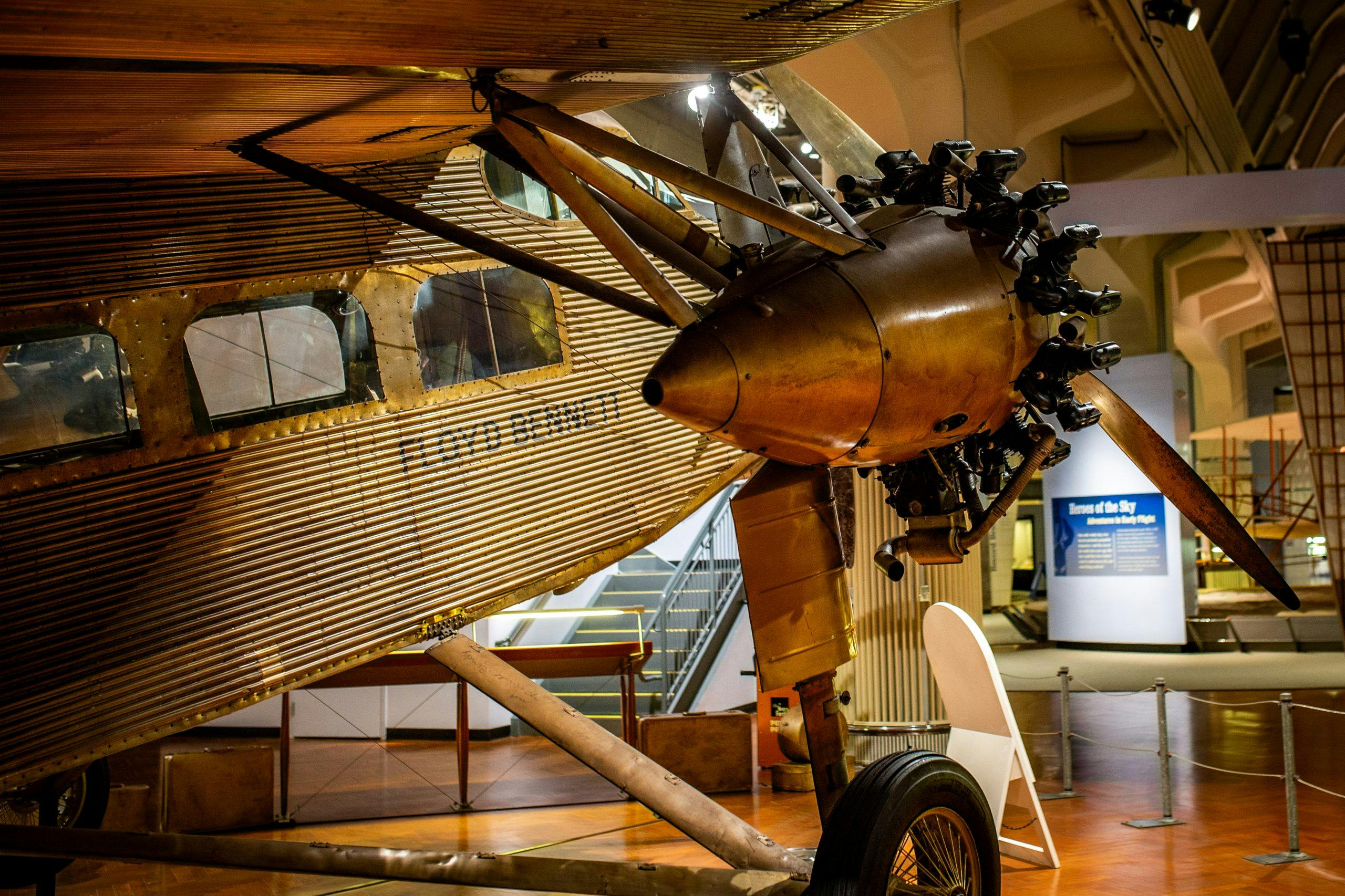

But what’s almost a CIA-grade secret is the great leap Ford accomplished between its Model T and Model 18. Momentarily bored by building cars, Henry and Edsel Ford launched commercial aviation with their aptly nicknamed Tin Goose. Though only 199 Tri-Motor aircraft were produced, Ford’s big bird was instrumental in lofting passengers, mail, and freight heavenward in the Roaring Twenties and Tough Thirties.

A Stout foundation

Ford ally Bill Stout was the jack of too many trades. He studied engineering at the University of Minnesota though illness caused him to miss the final exam needed to earn a degree. Undaunted, he served as the chief engineer for Packard’s aircraft division and later created the Stout Scarab precursor to Volkswagen’s passenger van.

During his lifetime, Stout was second only to Thomas Edison in the number of patents earned. He designed scores of model toys and covered automotive and aviation advancements for the Chicago Tribune and his own Aerial Age magazine. For years he employed the clever pen name Jack Knieff to shroud his identity. Stout’s credo—”simplicate and add lightness”—was cribbed by Colin Chapman in the 1950s.

During World War I, the global aircraft fleet consisted largely of open-cockpit biplanes with wood framing covered by fabric and reinforced with guy wires. Inspired by Fokker and Junkers’ advancements with metal construction and multiple engines shortly after the war, Stout designed and built what he called his Air Sedan in 1922.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Ford and Stout join forces

Thanks in part to Stout, the Fords became intrigued by the aviation business. When the company’s corporate charter was rewritten in 1919, a provision for aircraft manufacturing was added. At that time, dirigibles were considered the most practical form of air travel, so the Fords founded their Aircraft Development Corporation to pursue the manufacture of a lighter-than-air transporter made of metal.

Coincidentally, Ford’s material of choice was a new aluminum alloy called duralumin already in use by Stout. Formulated by the Aluminum Company of America (now Alcoa), this mix of aluminum, copper, manganese, and magnesium doubled ordinary aluminum’s tensile strength without increasing its weight.

Stout established the Metal Airplane Company in 1922 when a hundred Detroit industrialists were solicited to invest in his startup. Auto magnates Chrysler, Olds, Fisher, and Dodge and a dozen or so other investors took the bait.

In 1923, the Ford Motor Company’s chief engineer William Mayo paid Stout a visit to arrange a meeting with the Fords who were then producing two million Model Ts per year.

Hoping to retain control of his enterprise, Stout imposed a $1000 limit per investor. The wily Henry Ford was intrigued by the opportunity but sought a greater slice of Detroit’s newest enterprise. After a moment’s hesitation, he proposed a $2000 investment—$1000 from father and son. The shrewd Stout quickly agreed. When the news media caught wind, the senior Ford was quoted philosophizing that mass-produced aircraft would not only shorten distances between the globe’s citizens but also erase their misunderstandings.

Air sedan and air transport

Stout’s first all-metal plane was fitted with four seats. Initial tests were disappointing due to the Air Sedan’s modest 90 horsepower. Undaunted, Stout shared his thoughts with the Fords about the Air Sedan’s successor, dubbed Air Transport. This new high-wing, corrugated-duralumin aircraft, which was coded 2-AT, was powered by a single, 420-hp Liberty V-12. Its mission was transporting eight passengers or a ton of freight.

The Fords were sufficiently impressed to join other investors kicking in additional funds to keep Stout solvent. The 2-AT was christened Maiden Detroit, a play on the Made in Detroit label.

Despite two failed test flights, Stout’s 2-AT proved so airworthy that more than a thousand passengers reveled in joy rides in the summer of 1924. This rising enthusiasm for aviation underlined the need for a viable airport near Detroit. In pursuit of such a facility, Stout and a local dirigible manufacturer were invited to tour a 12,000-acre site the Fords owned in Dearborn.

The Blue Oval’s airport

Henry Ford offered to build Stout the world’s best landing field on property previously reserved for an employee subdivision. In addition to a pair of intersecting half-mile-long runways, Ford suggested construction of an adjoining factory for aircraft and dirigible construction. Following Stout’s eager acceptance of that proposal, Edsel Ford penned a Nation’s Business feature story declaring 1924 as the dawn of the aviation age.

The day following the Stout-Ford property inspection, hundreds of workers began reshaping the landscape with trucks and tractors. The senior Ford hired architects to design a sprawling factory and visited the construction site on a daily basis. Stout concluded his first sale—the Maiden Detroit to the U.S. Post Office for airmail transport—and the Ford Airport was officially dedicated in January 1925.

After constructing two grass runways, the Fords invested another $4 million in further improvements. Adding a dirigible mast, a passenger terminal, a restaurant, hotel accommodations, and concrete runway paving soon made this the world’s finest airport. With safe air travel as the goal, a weather bureau, traffic-control center, and radio communication office were also added. 70-foot-tall letters spelling FORD in white paint helped incoming flyers spot the airfield.

Ford’s 200-foot-long plant offered ample manufacturing space and offices for Stout engineers and executives. Stout christened the first 2-AT to roll of the line the Maiden Dearborn. Half a ton lighter than the typical car of the day, it had a 60-foot wingspan, a 46-foot length, and $20,000 price tag.

Ford takes over

More interested in operating an airline than manufacturing planes, Stout was immediately responsive to Ford’s take-over overtures. Cashing out other investors tried everyone’s patience but on July 31, 1925, Stout’s company became the Ford’s Metal Airplane division.

Three months earlier, Ford’s Air Transport Service had made its inaugural flight to Chicago carrying half a ton of freight. The round trip took five hours. Following the ship’s return, Edsel Ford reported to the press that the goal was not only carrying mail and freight between Ford plants but testing the company’s aviation advancements before carrying passengers. Round-trip service between Detroit and Cleveland commenced at the end of June.

Enter the Tri-Motor

Discussions with the U.S. Air Mail Service in Washington DC revealed that the 2-AT was deemed too large and cumbersome to efficiently carry mail. What was needed was a faster, multi-engine plane with the ability to fly through the night in adverse weather.

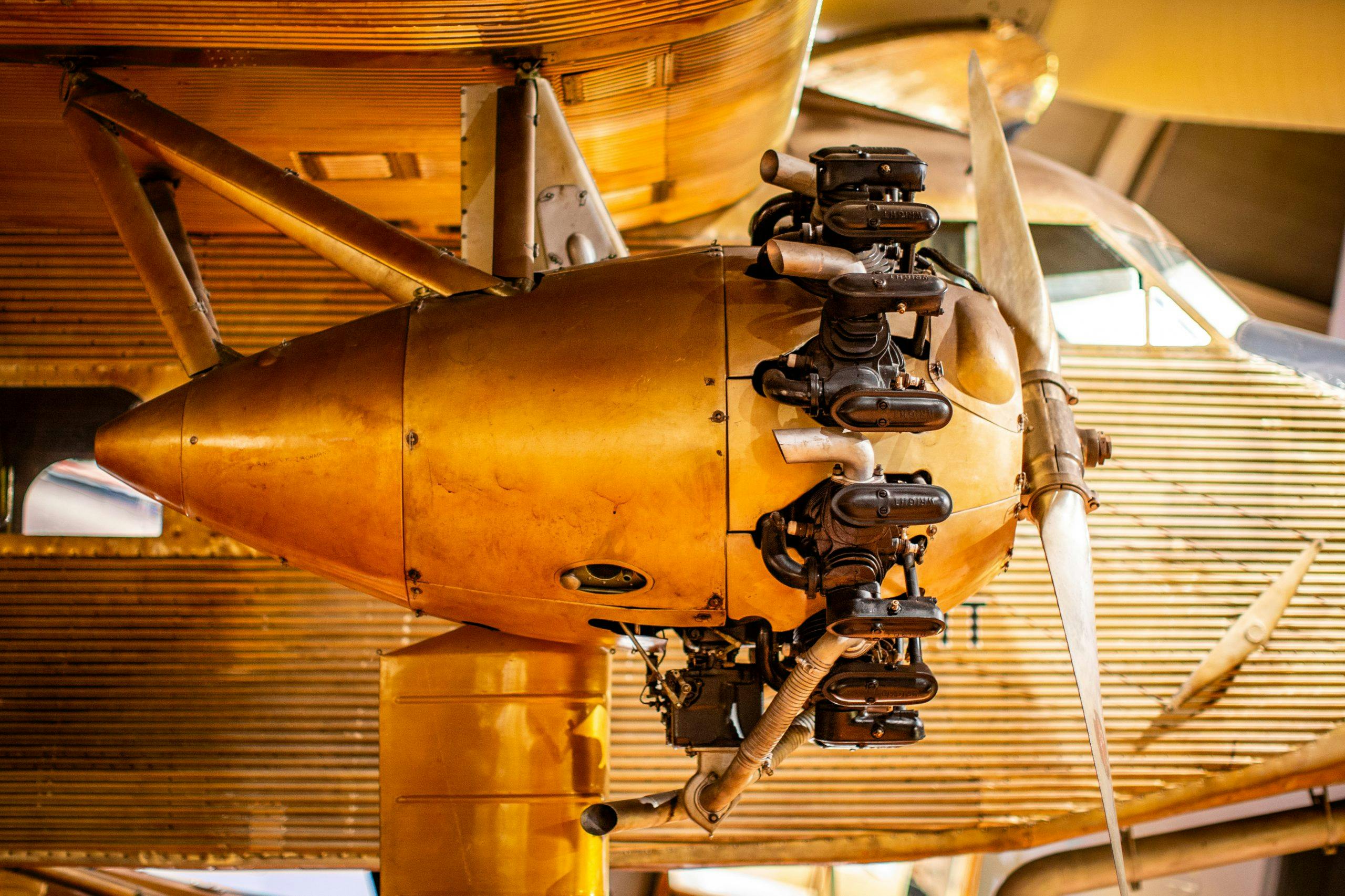

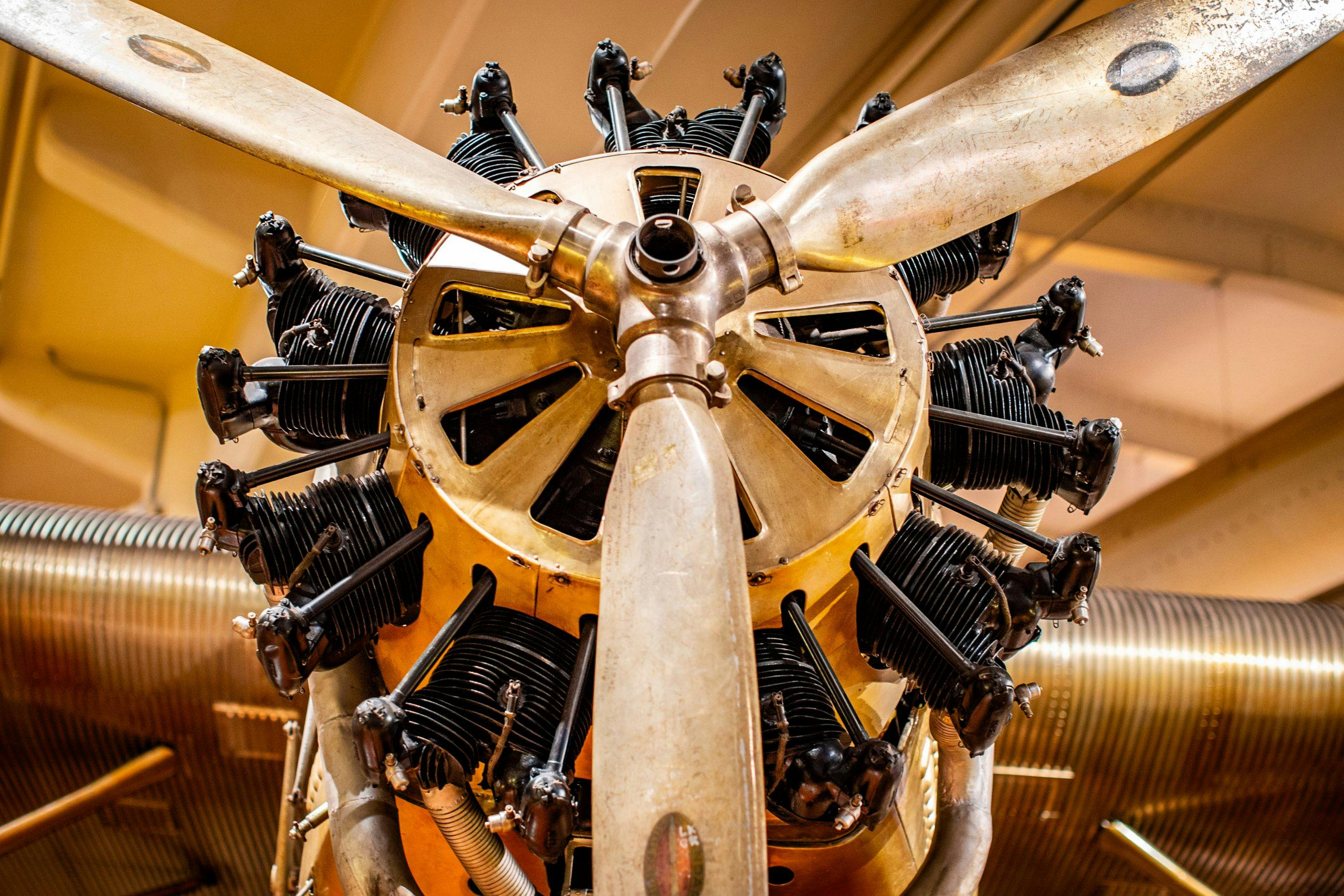

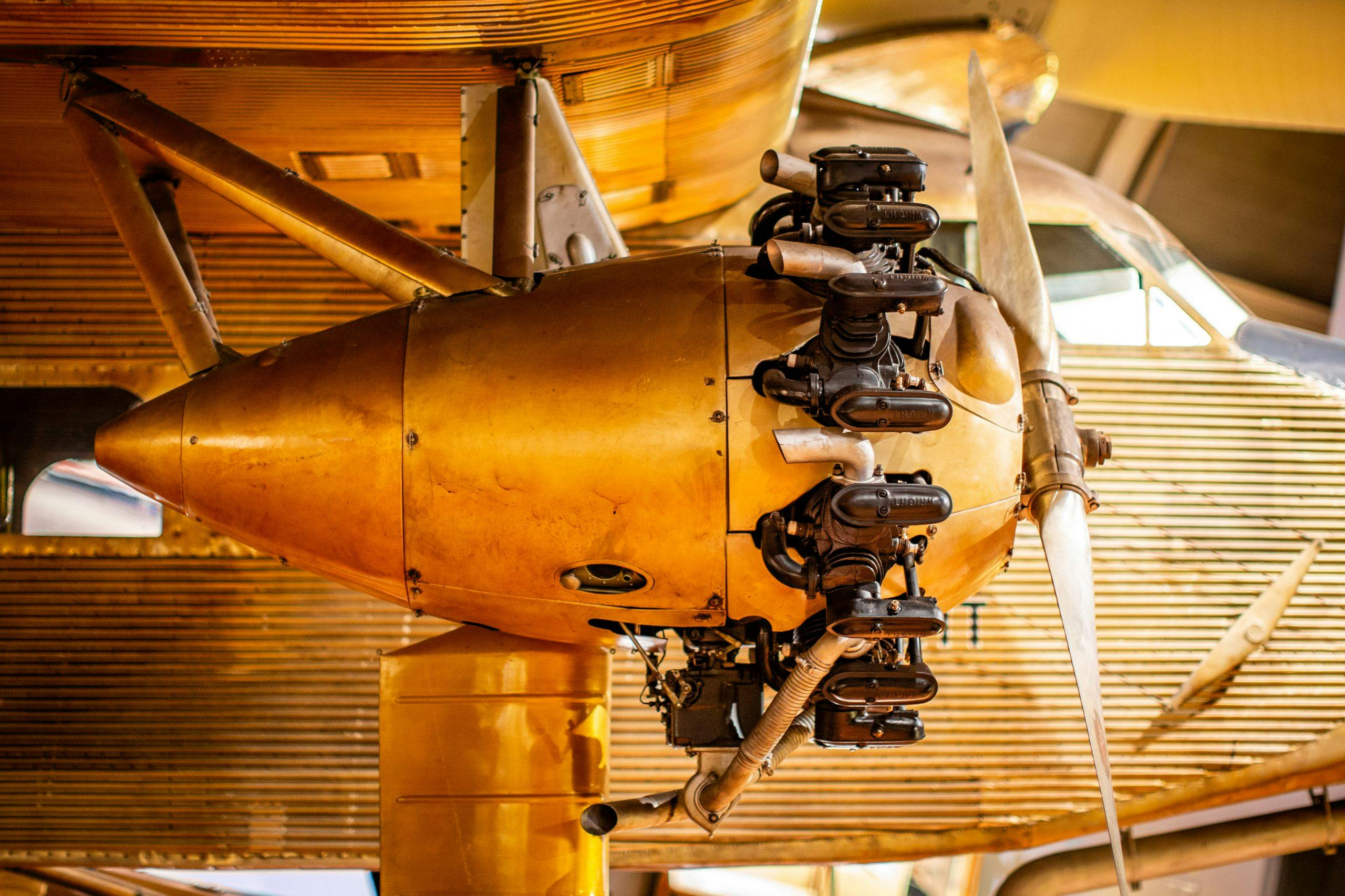

Stout, the Fords, and Ford chief engineer William Mayo agreed that a triple-engine plane was essential to progress. Luckily, the Wright Aeronautical Company had a new 200-hp, air-cooled, 9-cylinder radial ideally suited to their task. Three such engines were shipped to Dearborn and Stout begun designing another new plane. His game plan was to add two engines while retaining as much as possible of the 2-AT’s successful design.

By now, Henry Ford was more intrigued by aviation than by the car business. But when the Shenandoah dirigible crashed in September of 1925, killing all but one of the 41 passengers onboard, the Fords abandoned all hopes of manufacturing lighter-than-air craft to focus on Stout’s triple-engine design.

3-AT crashes and burns

Unfortunately, what Stout created was an ugly duckling. On its first test flight, the 3-AT lacked both stability and cruising speed. It couldn’t haul enough payload and was a handful to land. The two test pilots who flew it concurred that the design was a total bust.

Stout pleaded for time to develop his creation but the impatient Henry Ford had him banned from the design office. Overnight, trusted Ford engineer Harold Hicks became head of the airplane division while Stout remained on the payroll to promote Ford’s aviation interests.

Then a fire of suspicious origins wiped out the 3-AT prototype, all of Stout’s jigs and tools, four nearly finished 2-ATs, and the aircraft manufacturing building. Ford consoled Stout by noting: “It’s the best thing that could have happened. Now we can build the kind of factory we should have built in the first place.” Work immediately began to construct a three-times-larger factory and a 15-plane hangar.

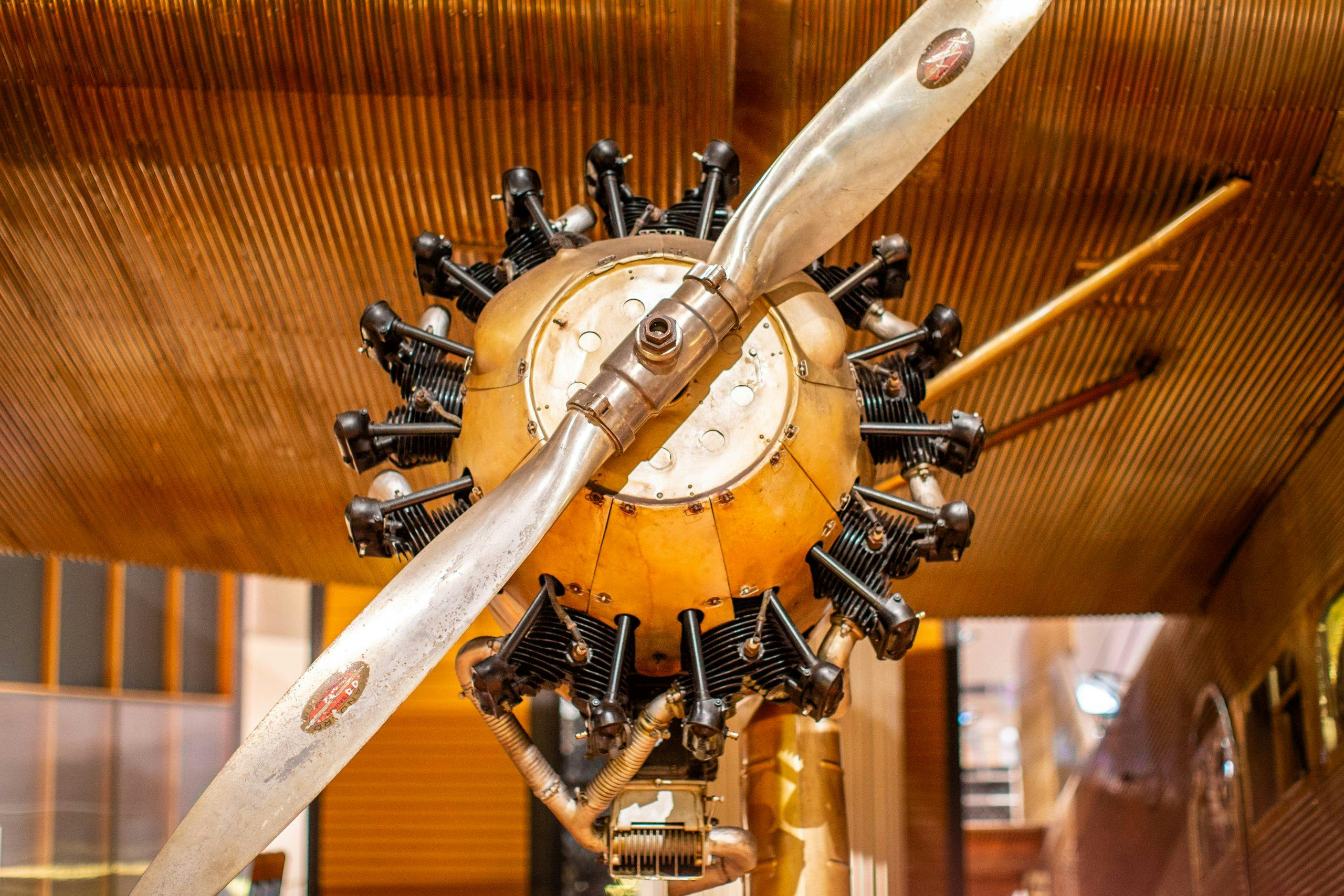

Rising from the ashes

In June of 1926, barely six months after the $200,000 fire, a vastly improved 4-AT was ready for its test flight. The center engine was positioned low in the nose and the fuselage tapered elegantly towards the tail. A thicker wing spanned 74 feet and overall length was just under 50 feet making the Ford Tri-Motor the largest plane built in the U.S. to date. Like automobiles of the day, the 4-AT used interchangeable parts instead of far less-efficient handicraft construction.

After the initial test flight, pilot Major “Shorty” Schroeder rushed up to Henry. “This plane’s got what it takes!”

Boasting 600 total horsepower and a streamlined design with no exposed struts or guy wires, the 4-AT could top 120 mph and cruise over 100. It could carry 1725 pounds, climb at 900 feet per minute, and reach 15,000 feet of altitude. For corrosion resistance, its duralumin skin was clad on both sides by pure aluminum and coated with lacquer. Feeding this Alclad sheet material between rollers created the distinctive corrugations that increased the finished panel’s stiffness. Wing tanks carried 271 gallons of gasoline.

The cockpit provided dual pilot and copilot controls, excellent visibility, and Model T steering wheels atop the control sticks. Cables to the rudder and elevators were routed externally.

Separated from the cockpit by a bulkhead, the 450-cubic-foot passenger compartment was furnished with an entry door and eleven wicker-covered, aluminum-framed seats. Lacking sound proofing, early passengers described the din as “a hundred gremlins hammering a barn door.” Cotton earplugs were provided free of charge. While cabin heat, tray tables, and seat belts were not yet fitted, every passenger did enjoy a spectacular view through large shatterproof glass windows.

The Tri-Motor’s selling price was $50,000 including a full tank of fuel. No competitor could match its combination of size, performance, safety, and all-metal construction. The first public demonstration of the plane awed representatives from four U.S. airlines.

Ford’s new 60,000 square foot factory was completed in early 1927 with two parallel lines producing two planes per week. Within the first month of production, the company had 15 Tri-Motor orders in hand. Initial customers included the U.S. Navy, Standard Oil, and Texaco. Ford car dealers became sales agents, and the company established a pilot training school in Dearborn synched to aircraft deliveries. One Ford dealer operated 16 Tri-Motors transporting freight up and down the West Coast, an operation later bought out by TWA.

Stout Air Services bought six Tri-Motors to carry passengers between Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago, charging $35 for a round trip from Detroit to Cleveland. That organization’s firsts included uniforms for flight attendants, hot coffee and sandwich meals, and limousine service connecting Detroit’s Book Cadillac hotel with the Ford airport.

In early 1927, a Tri-Motor flew from Dearborn to Dayton Ohio’s Wright Field guided solely by a radio beam operated by two Ford engineers. That technology was soon adopted by all airlines with Ford’s best wishes and no royalty fees.

Ford’s Air Transport Service became the world’s largest private airline by flying Model T parts and bulky manufacturing tools to car assembly plants around the Midwest.

Lucky Lindy comes to town

In May of 1927, Charles Lindbergh completed his flight across the Atlantic, giving aviation a major credibility boost. Three months later, when Lindbergh conducted his nationwide celebration tour with the Spirit of St. Louis, a second seat was fitted to that craft so that both Henry and Edsel Ford could enjoy their first flights over Dearborn.

Later that day, Lindbergh flew the Tri-Motor for an hour with the senior Ford again aboard and Ford’s chief pilot Harry Brooks serving as copilot. Ford likened the rides to going on a picnic, and said he wouldn’t mind taking a spin every day. But, except for one more flight several years later in a Douglas DC-3, Henry never again broke Earth’s surly bonds.

Aircraft business takes off

Contracts to fly mail by air on assigned routes for the U.S. Post Office prompted several airlines to purchase Tri-Motors beginning in 1927. Twenty-three new airlines were soon established to bid on airmail contracts and to fly executives and freight. There were 12 Tri-Motors sold that year followed by 39 more in 1928. The Ford factory was expanded to produce a plane a day.

As commercial aviation evolved from freight and mail service to passenger carrying, over 100 airlines ultimately flew Tri-Motors in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Central America, China, and Australia. During their fruitful life, Tri-Motor advertisements bragged that “no Ford plane has yet worn out in service.” They successfully flew sightseers over the Grand Canyon for 65 years. In 1932, presidential candidate Franklin Roosevelt began replacing his whistle-stop train trips with Tri-Motor hops.

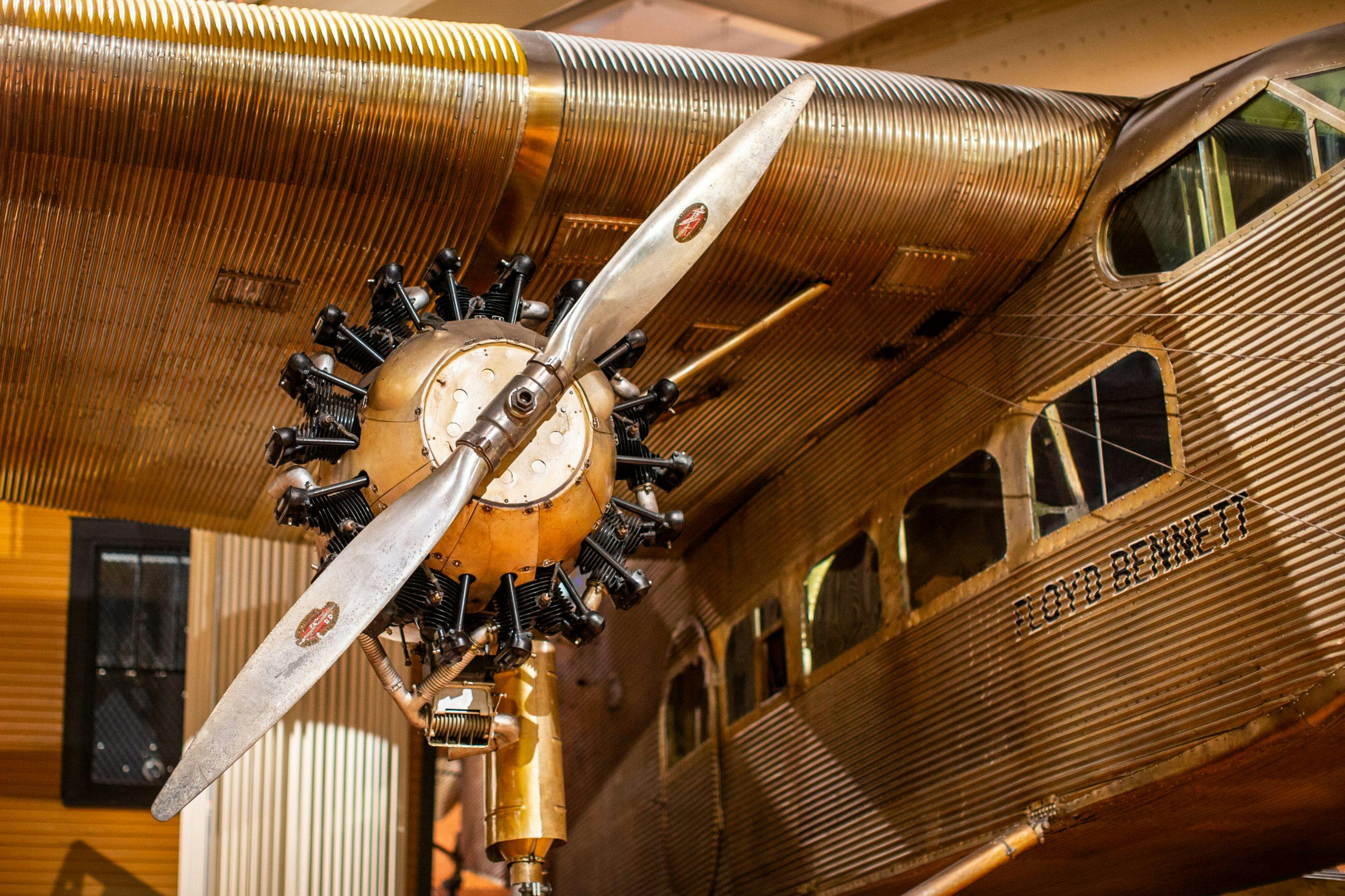

Epic expeditions

In 1929, a special Tri-Motor was prepared for Rear Admiral Richard Byrd’s first-ever visit to the South Pole. Alterations included a larger wingspan, a 525-hp Wright Cyclone center engine spinning a three-blade prop, and additional fuel capacity. Byrd and a crew of three flew 1600 miles in 18 hours in late November but had to dump 250 pounds of food to clear a 10,000-foot pass en route. After achieving its flyover, Byrd’s team left their plane in Antarctica to journey home. Five years later, Byrd returned to find his Tri-Motor snow-covered but otherwise in excellent condition. In 1935, the craft came home by boat and remains on display at Dearborn’s Henry Ford Museum.

Continuing development

Over the years, Wright Whirlwind engine output rose from 200 to 300 horsepower, gradually improving the performance of the 79 4-AT Tri-Motors manufactured from 1926 through mid-1929. Following a suggestion from Lindbergh, Ford engineers redesigned the plane around new Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines developing 420 horsepower. The new 5-AT Tri-Motor was 1000 pounds heavier, 5 mph faster, and could carry twice the payload thanks to its longer fuselage.

Four distinct 5-AT generations were built from mid-1928 through mid-1933 with prices starting at $65,000, increasing the total Tri-Motor run to 199 planes, not counting experimental builds. Adding floats or skis expanded their service to otherwise inaccessible destinations. During World War II, the Flying Tigers successfully flew Ford Tri-Motors in Italy and China.

Ten Tri-Motors were purchased in 1929 by Transcontinental Air Transport to initiate coast-to-coast passenger service. Lindbergh lent his name to the enterprise which flew by day and used Pullman rail service and comfortable hotel rooms at night. A one-way trip cost $352.

Following rail service from New York to Columbus, Ohio, passengers flew to Waynoka, Oklahoma, with four intermediate stops followed by ground travel to Clovis, New Mexico. The final leg was via Ford Tri-Motor to the Los Angeles suburb of Glendale. Cruising speed was 100 mph, soaring over the rutted, single-lane mud roads below. The entire trip consisting of 2343 air miles and 970 rail miles took 48 hours, roughly half the time required by rail alone.

For reference, the first ever cross-country trip by car in 1903 took 63 days. When the paved Lincoln Highway opened a decade later, a trip across the country could be completed in as little as 20 days.

Flights of fancy

Henry Ford’s imaginative mind wandered in some unlikely directions. Convinced that 100-passenger seating capacity would be necessary to make scheduled service practical, he had Ford engineers investigate a six-engine craft boasting 6000 horsepower, a 125-mph cruising speed, and 700 miles of range. At the opposite end of the spectrum, his tiny single-seat “flivver” was aimed at inexpensive commuter travel. Lindbergh, who barely fit in an experimental example, did succeed in flying it briefly.

Ford’s chief pilot and close friend Harry Brooks broke the distance record for small planes in the flivver. Unfortunately, he disappeared off the Florida coast in February 1928 after the engine in his aircraft sputtered. That loss prompted Henry Ford to abandon his pursuit of a Model T for the air.

Endgame

In the fall of 1929, the Wall Street crash triggered the Great Depression, driving customers contemplating the purchase of an expensive aircraft into hiding. Except for a few planes sold to the U.S. Army Air Corps and the Marine Corps, sales were bleak. Government subsidies kept the major airlines alive by paying them to fly mail and passengers over long distances. Small airlines were quickly purchased by the majors resulting in conglomerates such as TWA.

The last Tri-Motor was finally built in mid-1933 for Pan American Airways. At this juncture, the car side of the business was equally dismal. Ford’s hot V-8 struggled to draw customers into showrooms, achieving barely 300,000 sales per annum. Ford’s seven-year Tri-Motor production run quietly ended, in large part because it was never a profitable enterprise. The 1932 books recorded a net loss over $5 million.

Once the global economy finally settled down, Boeing and Douglas took over as the dominant aircraft manufacturers with 247s, DC-1s, -2s, and -3s. James McDonnell, who later established the McDonnell Douglas combine, learned the ropes of the aviation business as a fresh-out-of-MIT Ford/Stout engineer.

The Tri-Motor was the first practical, modern commercial aircraft. It was instrumental in carrying freight, mail, and passengers in relative comfort. The Ford Airport was the prototype of all subsequent fixed-base operations. The Ford Motor Company convinced Americans that aviation was both safe and dependable.

Postscript

Henry and Edsel Ford did enjoy one more aviation fling. During World War II, they constructed 8685 4-engine B-24 bombers in a huge plant they built on farmland 18 miles due west of the company’s Dearborn headquarters.