Media | Articles

The Mystic Cobra, the hundred dollar bill, and the Secret Service

Picture an ordinary bodyshop paint booth: brightly lit, bare-walled, nearly spotless. The painter steps up, air-powered paint gun in hand, and aims the nozzle carefully at a masked-off part of a mid-’90s Ford Mustang. If there is a weird part to this fairly typical process, it’s the observer—an agent from the U.S. Secret Service, watching the repair work with an eagle eye.

The reason he is there is loaded in that paint gun. Instead of ordinary paint, it’s a shade called Mystic, technically colorless but capable of making light dance along a surface. In this application, the paintwork will return one of just 2000 Ford Mustang Cobra coupes to its former glory, a shade that seems purple, but shimmers to the eye. It’s the other application for Mystic that has the Secret Service standing by; the same paint going on that Mustang was used to print the U.S. $100 bill.

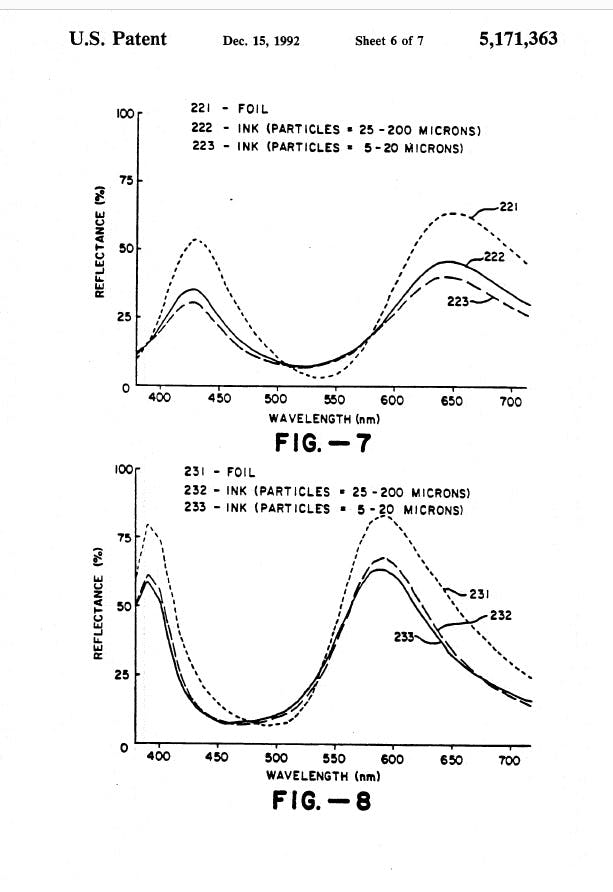

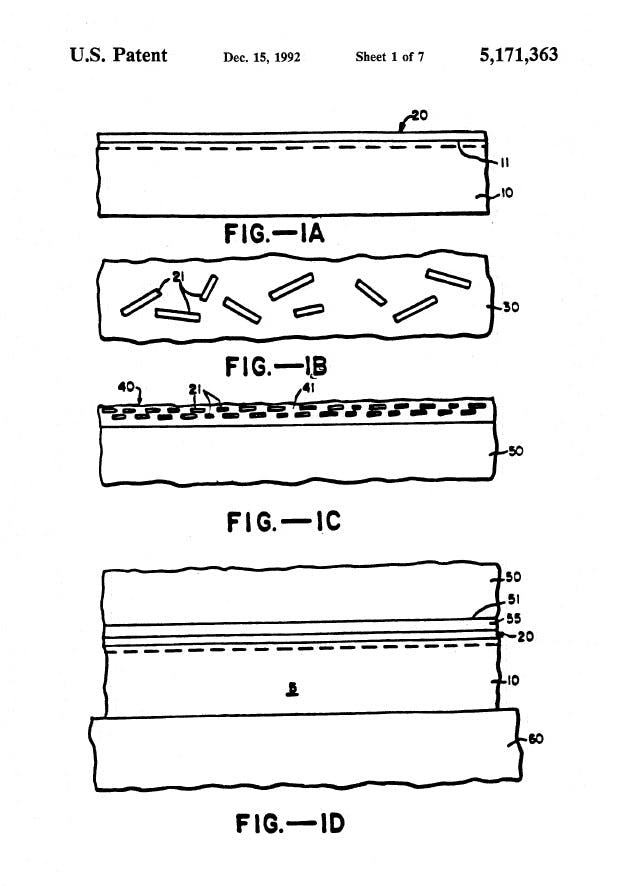

Baden Aniline and Soda Factory—better-known as BASF—acquired a smaller company called Flex Systems in the early 1990s. BASF was interested in creating holographic inks specifically for the production of currency, and Flex had expertise in the field. Specifically, it had come up with a technology for suspending tiny prisms in liquid paint, which would align as the paint dried and split light along the visible spectrum. The paint tech was patented as Prism Platelets.

You probably remember how a prism functions from your high school science textbook or the cover of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. Visible light, which appears white to the human eye, hits the angle of a glass (or other transparent material) prism and is slowed down and split into various wavelengths. The shorter the wavelength, the deeper the color, right down to indigos and purples.

Flex’s genius was in figuring out a way to turn paint into prisms by suspending tiny platelets in the liquid. When wet, the fluid didn’t look particularly special. When applied to a flat surface, like a banknote, the prisms lined up flat, overlapping each other. Slide a note printed with this ink under a light, and it had a holographic effect that was difficult to reproduce. Tough luck, would-be counterfeiters.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Treasury department was looking to redesign the $100 bill in order to make it harder to fake, and Flex’s “prism platelets” were just the kind of cutting edge security tech to do it. A deal was struck, and BASF supplied the ink to the U.S. Treasury’s printers.

This special ink didn’t have any innate color itself, as it was the light-splitting that created the hues. However, adding in toners to the batch let the mixer change what the paint looked like when light hit it. It also varied depending on what kind of surface you sprayed it on. BASF started thinking about cars.

Color-shifting paint was not a new idea in 1995. Customizers had been experimenting with metallic flake in paint, from the SoCal Kustom Kar scene to wild-looking drag racers.

However, BASF’s pitch to Ford was the prospect of building the first production car to feature color-shifting paint. The BASF sales team carefully explained how the process worked. Ford wanted to see it on a car first. Two 1995 Mustang GT convertibles were sent to BASF for test-painting—the first two Mystic Fords.

But those were internal projects. As far as the public was concerned, the first Mystic Mustang wasn’t a Ford, but a Saleen. The long-time customizer brought a Mystic-painted S351R Speedster to SEMA in 1995, and the car got plenty of attention. Seeing the positive feedback, Ford decided to move ahead on production.

Originally, only 1999 customer cars were to receive the Mystic treatment, all of them 1996 Mustang Cobra coupes. However, an additional 1996 coupe was painted first for PR duties, and it somehow later made its way into private hands.

All of the Cobras started out life painted black. Ford shut down the Dearborn production line, so all of them could be painted at once. The paint process itself wasn’t unusual, just a base coat, the Mystic layer, and then a clear coat over top. The paint code for Mystic was designated LF, and the price for the option was $1152. Almost all the cars came with black leather interiors, and all had the then-new handbuilt 4.6-liter V-8 good for 305 hp.

As it was blended with toners, it’s not like you could just load liquid Mystic into your inkjet printer and print off a hefty stack of Benjamins. However, careful filtering of the paint would yield those prism platelets, which could be added to ink and used to create nearly undetectable forgeries. Ford paint code LF would have to be a tightly regulated substance. You have to imagine the Feds blew a gasket when BASF told them Ford was painting entire cars with its counterfeit-proof ink.

However, Mystic was at least a limited edition, so there were only 2000 cars out there. Even better, used Mystic is useless to a would-be counterfeiter, as the prisms are unrecoverable when dried. It was only the liquid paint that needed to be carefully monitored. But then the next problem reared its head, one that would be familiar to anyone who has watched a montage of Mustangs leaving Cars & Coffee events.

Unless they’re mothballed in a collection, Cobras get crashed, or they get crashed into. That means a bodyshop has to get involved, and you can’t just send a gallon of anti-counterfeit ink to to Al’s Fender-Bender Hospital and hope that none of it walks off the premises. No offense, Al.

The solution was to first check the VIN of any car being repaired to ensure it was actually a Mystic Cobra, and then to dispatch a supervisor. The supervisor could be a trusted Ford or BASF employee, but often Treasury and Secret Service agents were also sent into the field. They’d guard the paint, even helping with post-paint cleanup to ensure every drop of Mystic was accounted for.

Repairing a Mystic Cobra was doubtless one of the more stressful jobs a paint booth tech would get. Thankfully, repairs were rare, as Ford only did that one single run of Cobras with Mystic paint.

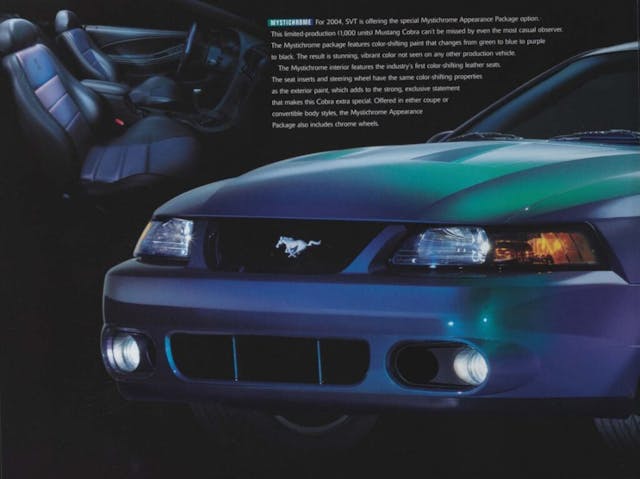

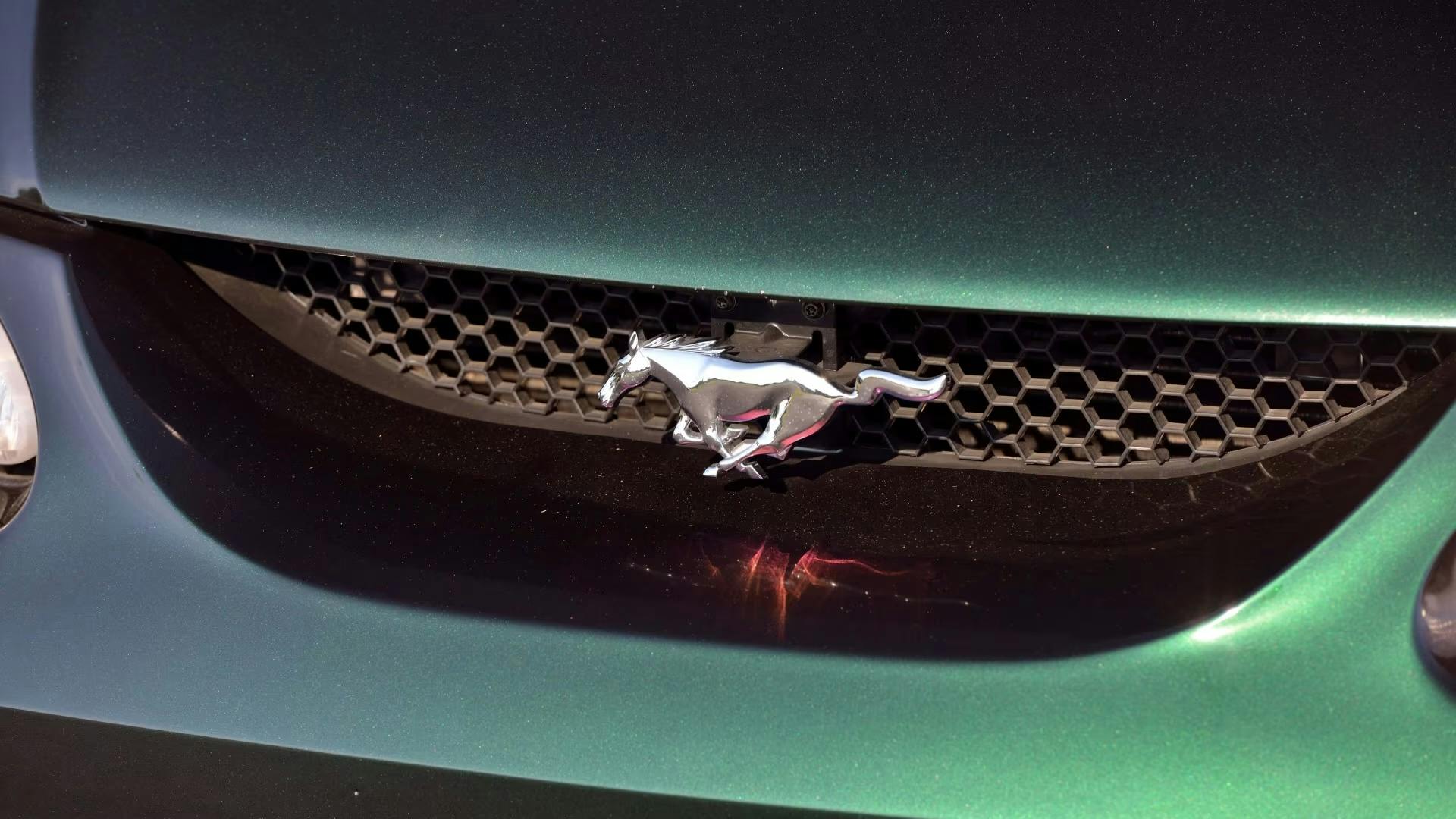

Later, however, the similar Mystichrome paint came along. Available on the supercharged 2004 SVT Cobra (code-named Terminator), this shade celebrated the Mustang’s 40th anniversary and extended to some interior parts. The paint code was now different from Mystic, and the paint didn’t need to be so highly supervised. Any bodyshop with the proper PPG Platinum certification can repair a Mystichrome Cobra. However, it’s still a stressful job, as the paint costs an eye-watering $26,600 per gallon.

In 2020, a tech entrepreneur named Justin Choi paid $100,000 to have his Ford GT painted in Mystichrome. It was a one-off, with Ford promising that no other GT would receive the treatment. It’s a pretty special car, and Choi sees the paint choice as a tribute to his uncle, who sold Fords in the Los Angeles area and was forever bringing home Blue Oval hats and jackets for his nephew.

But for the rest of us, the door is still perhaps open for a color-shifting paint treatment for some future Mustang model. It is, after all, coming up on 20 years since the Mystichrome Cobra, and both it and the original Mystic Cobra are still desirable collector items.

If you have one of these rare machines for sale, it’ll be sure to fetch many, many banknotes with Benjamin Franklin’s face on them. But if the buyer idly mentions working in a paint booth, make sure you check those notes carefully before handing over the keys.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Chrysler used the same paint on a’96 LeBaron convertible show car, except that theirs was a much prettier sort of purplish color. They had a production color that was very similar but didn’t shift colors as dramatically as the printer paint.

I have a 1998 Mustang Cobra Svt with original white paint in perfect condition. My brother had it stored in the garage. Now I have it and having fun with it

I don’t believe the facts on this one. The ink used on US Currency is called optically variable ink. When I went to training at JJRTC (few people know what this is offhand), this was never mentioned, nor was it ever mentioned in any follow on trainings or updates received while working counterfeit. We were told the ink was made by a single overseas source at the cost of $700 per ounce if I recall correctly. Doubtful Ford would have sprayed a car with paint that costs that amount Additionally the optically variable ink only changes from one color to another, and in the early bills, went from green to black and in the later bills, green to copper. Don’t believe me….grab a series 1996 C Note and look for yourself. While a cool story, not sure it’s accurate.

While the cost of the paint in the article is very wrong. The story of how and where the paint was made and originated is true. I spent the better part of 10 years researching the paint on the cars. I own a couple of them. 80% of the information on this article, as well as the pictures of the patent information was sourced from one of my sites and was not cited by the author because he re-worded it thoroughly.

I have a 1998 ford mustang cobra svt and I love it!

Even tho I’m a year late, I have to add my 2 cents. I worked at a Ford dealer at the time, and we had one Mystic Cobra. One of the problems with this paint is you cannot photograph it! Well, you can, but you do not get the color change when you view it in person. I remember the purple being the dominant color, but the green, as shown in the pics, would easily show if you just moved a bit, especially in the sunlight. I think I remember the paint cost $1000/gallon in 96- that was a LOT of money! Also, the one at our shop is the only one I have ever seen.