Media | Articles

The improvised, tortuous birth of Vietnam gun trucks

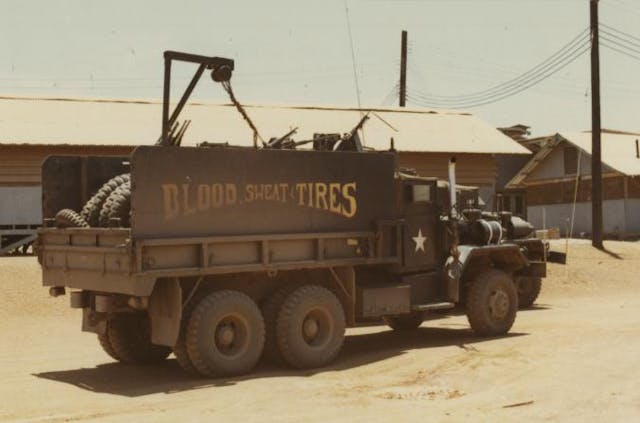

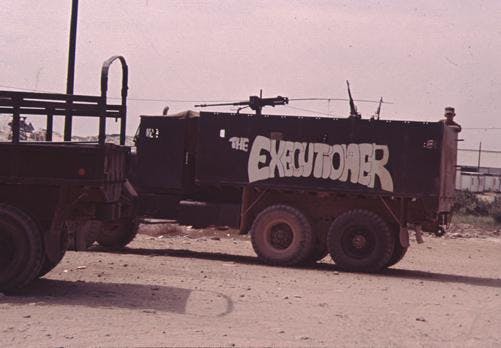

Eve of Destruction, Instant Death, The Executioner, Blood Sweat & Tires, Brutus, Cold Sweat, The Creeper.

The names of Vietnam gun trucks read like a heavy metal setlist. With exteriors slathered in black and enough firepower to level a cattle stampede, U.S. gun trucks ruled the roads of Vietnam by late 1967. However, these beasts weren’t thoughtfully engineered affairs that arrived alongside U.S. troops in 1961; they were haphazardly developed in the Vietnam jungles by U.S. soldiers desperate to protect their supply lines.

The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (V-C) were a stubborn, frustrating enemy. Wherever American forces slogged, the Viet Cong seemed to swim. Their guerilla tactics and intimate knowledge of their surroundings made the native forces slipperier than a bar of soap, and many U.S. soldiers fell victim to their infamous ambush attacks. Ultimately, over 58,000 Americans were killed in action.

American trucking convoys found themselves motoring into the crosshairs of such traps. Lightly defended and initially undermanned, these supply chains were the life lines of the American war effort—and easy targets to boot. NVA predators sought to block ammunitions and gear from reaching troops and, most importantly, to prevent jet fuel from reaching airfields. Their grand epiphany: It was much easier to neutralize America’s advantage in the sky by keeping the planes grounded in the first place.

After suffering catastrophic loss of supplies, G.I.s put their heads together to determine how to defend their white-knuckled, truck-driving brethren, and so began the evolution of the Vietnam gun truck.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Growing pains

Americans were in dire need of increased convoy security. At first, confusion reigned: Who was responsible for supply line security? What might effective protection look like? Transportation Corps Historian Richard E. Killbrane writes:

It was not a question of whether the SOP (Standard Operating Procedure) for reaction to an ambush was adequate as none of the drivers knew it. They had never had a need to. The 8th Transportation Group would have to look at both active and passive measures to protect the convoys.

Since supply routes frequently traversed narrow mountain passes between check points, convoys could be particularly difficult to defend. The highly mobile Viet Cong trapped the heavy laden, trundling convoy in these bottlenecks, areas that the U.S. Army soon knew as “kill zones.” Simply weaponizing drivers wouldn’t solve the problem; halting the convoy to return fire delayed the arrival of the much-needed supplies, and in the chaos of a skirmish, roles easily became muddied.

The default tactic was to keep the roadway cleared at any and all costs and either persist through the kill zone and drive on to the refuge of the next checkpoint or, if absolutely necessary, return to the previous one. Both of these evasive maneuvers required some offensive from an aggressive security detail.

Do what you can with what you’ve got

Guns + truck = Gun truck. The concept was simple. Swiveling, bed-mounted guns could target attackers hiding in craggy mountain passes and provide a fighting chance for the convoys. Initial designs were primitive and evolved from what was available and familiar: the plethora of medium-duty trucks, like the deuce-and-a-half. The machines emerged mundane, nameless, and a distant cry from their fully realized form. The first iteration used lumber and sandbags to mount guns and provide a barrier for their operators, but rear suspension failures were common; mounting a bunker on what was essentially a flatbed left much to be desired. Still, Army engineers were on to something and better materials soon became available. As Killbrane documents in an interview with former LTC John Burke:

The new 2 ½-ton gun trucks were built from precut steel plating that had been ordered during the summer. It arrived just after the 2 September ambush. The battalion commanders directed the construction of gun trucks; company commanders picked the crews and left the design to them. The crew consisted of a driver, NCOIC armed with an M-79 grenade launcher riding shotgun in the passenger seat of the cab and two gunners with M-60 machine guns standing in the gun box. When ring mounts arrived, some crews added an M-2 .50 caliber to the cab. The new gun truck was a dedicated weapons platform which could maneuver to protect task vehicles.

Protect they did.

At the onset of an attack, it was the gun trucks’ duty to evaluate where the greatest threat lay, address the threat, and lay down as much suppressive firepower as possible so the supply trucks could escape. The Viet Cong attackers weren’t fazed by the stouter defense for long, however, and quickly adapted. The NVA maximized the advantage of surprise and learned how to block an escape and corral vulnerable targets.

No two attacks were exactly the same, and, while the trucks bolstered the convoys’ odds of survival, neither the U.S. nor the Viet Cong proved dominant. U.S. convoys, which could stretch over a mile long, needed to figure out how to optimize their response time and mitigate losses. The solution was as simple as the initial concept: more trucks and bigger guns.

Upgrades and identities

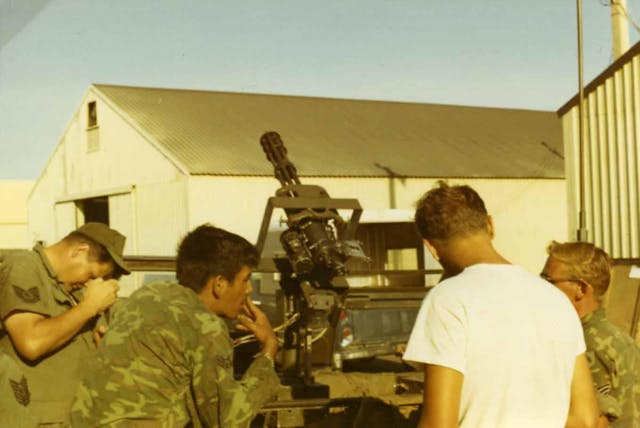

In a matter of months, gun trucks evolved from repurposed 2.5-ton worker bees into purpose-built 5-ton fighters, with newly improved double-walled steel gun boxes. Supersizing the trucks brought better power, improved handling, and more room for ammo and gun mounts. There was no standardized configuration when arming these trucks; the task was primarily left up to each vehicle’s crew. Teams scrounged around, bartering for their weapons of choice in the box. Unsurprisingly, the three most sought-after weapons were the M60 machine gun, the M02 .50-cal Browning, and the M134 minigun.

Each weapon brought a distinct skill set. The M60 was relatively versatile and allowed for easy mounting and dismounting. If placed on a swiveling mount, it could cover any angle from floor to sky. The .50 cal Browning was a wartime staple, providing a chunky punch and superior penetrating power. Gun crews typically mounted an M02 over the front of the cab or on the rear. Some trucks, like Eve of Destruction, famously bundled together two .50-cal units as a rear guard. The minigun, like the M60, was chambered for the smaller 7.62 mm round but spat ammo at the most deadly firing rate of the three: With six rotating barrels, the M134 dispensed an astonishing 2000 to 6000 rounds per minute (rpm). Collectively, these three weapons could splinter swathes of jungle in seconds.

For the most part, the gun boxes successfully protected their crews from the Viet Cong’s heavy onslaught of small-arms fire and projectiles. However, the crews were vulnerable to rocket-propelled arms and explosives.

A hero in the legacy of the Vietnam gun truck crews was a man by the name of Larry G. Dahl, a posthumous Medal of Honor and Purple Heart recipient for his actions aboard the gun truck Brutus. After arriving to the aid of a fellow convoy further along their route near An Khe Pass, crews on The Untouchables, The Misfits, and Brutus contained the skirmish and, once the fight appeared to be over, prepared to leave. They were mistaken. Another scuffle erupted, and a grenade flew up, over, and into the gun box of Brutus. Dahl saw it first. Without pause, he leaped onto the explosive, smothering the detonation and saving the lives of his crew at the price of his own.

To this day, gun truck veterans remember Dahl’s actions and shared his mindset. It’s an unspoken bond, one built through the selfless insanity of their job and, along with the names stenciled on the boxes of their trucks, branded forever in their memories.

Where are they now?

Nearly all of the original gun trucks in Vietnam remained on the other side of the Pacific. The one documented exception is Eve of Destruction, which you can find at ease in the U.S. Army Transportation Museum, in Fort Eustis, Virginia. Recreations have been made, chiefly a commemoration of Dahl’s truck Brutus, which is now part of the Military Veterans Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

Replicating a gun truck can be a fulfilling and attainable hobbyist endeavor, largely because gun trucks’ configurations were so improvised in-period. The chief task is acquiring a deuce-and-a-half or 5-ton rig. Neither truck is too difficult to source, but 5-ton vehicles are generally harder to come by than their little brothers and come with harsher state registration regulations, depending on your neck of the woods. Cost also varies between the two; a deuce-and-a-half typically runs between $2500 and $4000, and a 5-ton, as a general rule, costs about twice that ($5000–$8000+).

Veteran support and community is alive and well in pockets of the internet, whether you’re looking for stories, research, or auctions of gun trucks replicas. The efforts of Vietnam era truck crews continue to pave the way for the modern generation: Convoy defense consulting has been greatly bolstered by the vast breadth of ‘Nam-era knowledge. Though they may no longer be in uniform, the original crews continue to serve by supporting U.S. soldiers doing convoy security in conflicts as recent as the Iraq war.

Do you have any records of these gun trucks like ID numbers as I believe I have one?

Check with Matt Seelinger, Chief Historian of the Army Historical Foundation. If it can be found, he will find it.