Media | Articles

The harebrained idea to help horses get used to horseless carriages

It was the turn of the century and the dawn of the automotive age. Given that major cultural shifts rarely come to pass without a hiccup, the advent of the motor car and its internal combustion engine was not without its problems. For instance, how do you make the switch from horse power to horsepower a little easier on the real horses?

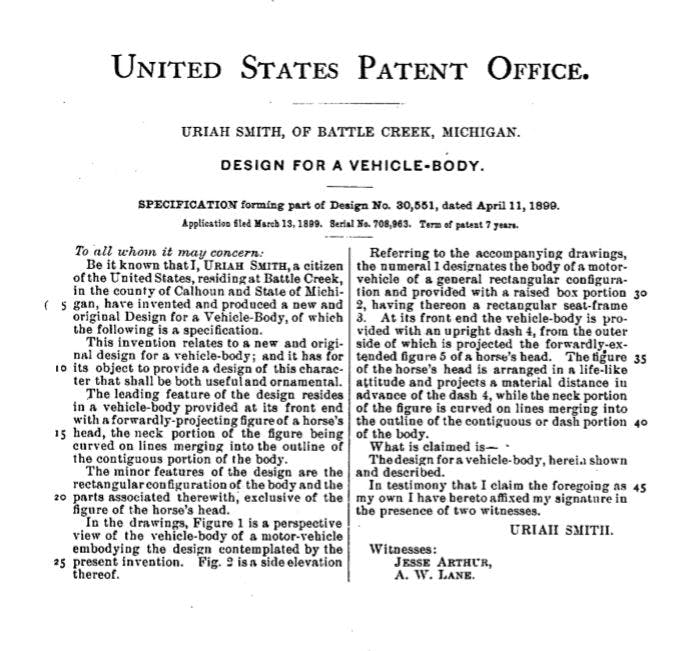

Enter Uriah Smith, a Seventh Day Adventist preacher and inventor from Battle Creek, Michigan. Smith’s main objection with cars was that they scared the hell out of the four-legged transportation of the day, resulting in accidents and death. He figured the best way to calm a horse when a car drove past was to make that car look a little less foreign.

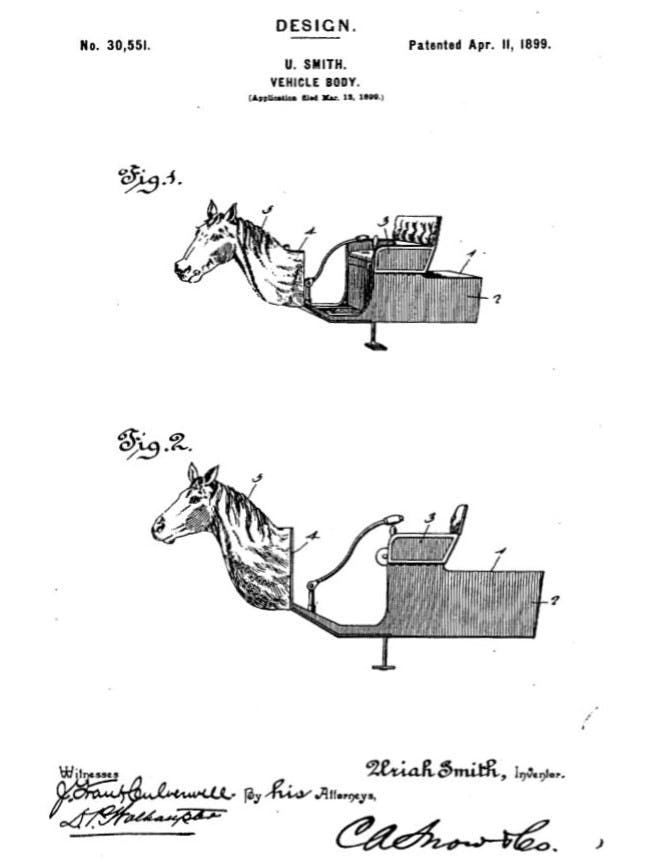

So, in 1899 Smith introduced the Horsey Horseless, a huge wooden horse head that could be strapped to the front of a motor vehicle. In his patent application, Smith described the Horsey Horseless as a “new and original design for a vehicle body… that shall be both useful and ornamental.” He forgot odd. Kind of like pulling a moose head off the wall of a hunting cabin and slapping it on the front of a Jeep.

Smith, however, thought it made perfect sense. “The live horse would be thinking of another horse, and before he could discover his error and see that he had been fooled, the strange carriage would have passed, and it would then be too late to grow frantic and fractious.”

The Horsey Horseless was also helpful, Smith reasoned, in that it was hollow, so it could house an additional fuel tank. What he didn’t consider, perhaps, is how poorly a horse might react to the sight of a fellow Equidae’s head exploding, should it meet with a well-placed spark.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

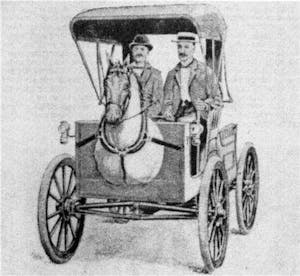

According to Pacific Standard magazine, Smith wasn’t the only one granted a patent “to put the horse back into the horseless carriage.” Five years later, in 1904, Denver’s Henry Hayes was given a patent “for a motor vehicle attachment which, when applied, makes it look like there’s a horse pulling your vehicle.” Hayes’ device had an oil lamp concealed inside the head of the horse to light the way (there’s that fire hazard again), and a rope that, when pulled, closed the horse’s mouth and sounded a horn.

Pacific Standard found a newsreel, produced by Popular Science and released on April 30, 1937, that demonstrated Hayes’ invention. The contraption wasn’t original, but it was built from Hayes’ specs:

“You remember the gasoline go-kart of the Gay Nineties? The driver of that day was a daring crusader whose reckless adventures on the road made him a shocking nuisance to both man and beast. When horses actually stood on their hind legs in protest, something had to be done about it. So inventor Henry Hayes, on December 13, 1904, patented an idea for the preservation of highway etiquette. Why not set the horse an example? Shame him into the march of progress. Perhaps this dazzling equipage will stop his tomfoolery. They used to yell, ‘Why don’t you get a horse?’ So right from the family tree came Wildwood. He improved the appearance of the car and created the impression of an extra horse power.”

There’s no proof that Smith’s or Hayes’ inventions were ever produced beyond the prototype stage—most likely because they simply didn’t work. Lauren Fraser, a horse behavior consultant in British Columbia, told Wired in 2015, “A horse would not be fooled. The animals deserve—but don’t always receive—a bit more credit than that for their intelligence.”

Obviously, horses simply grew accustomed to sharing the road with motor vehicles. In the end, it would have been a lot more difficult for drivers to get used to those crazy-looking wooden horse heads.