Media | Articles

The first motorized vehicle to cross the U.S. wasn’t a car—it was a bike

George A. Wyman made a name for himself as a bicycle racer, but he reached legendary status when, 119 years ago, he rode a motorized two-wheeler from San Francisco to New York to become the first person to cross the North American continent aboard an engine-powered vehicle.

Wait, you might ask. Doesn’t that distinction belong to Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson? Not quite. He has just received more publicity over the years, including a documentary by Ken Burns. Wyman actually beat Jackson by nearly three weeks.

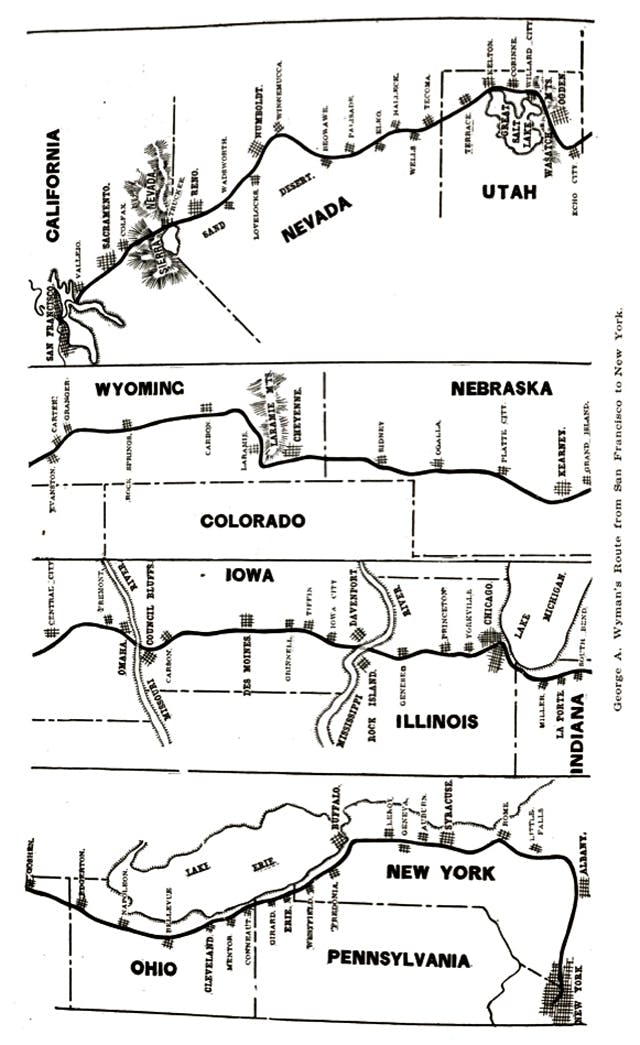

Riding a 1902 California Motor Company motorbike (designed by Roy C. Marks) and traveling 3800 miles in 51 days, Wyman arrived in New York City on July 6, 1903—three days after his 26th birthday and 20 days ahead of the more-celebrated Jackson, who became the first person to cross the continent by automobile.

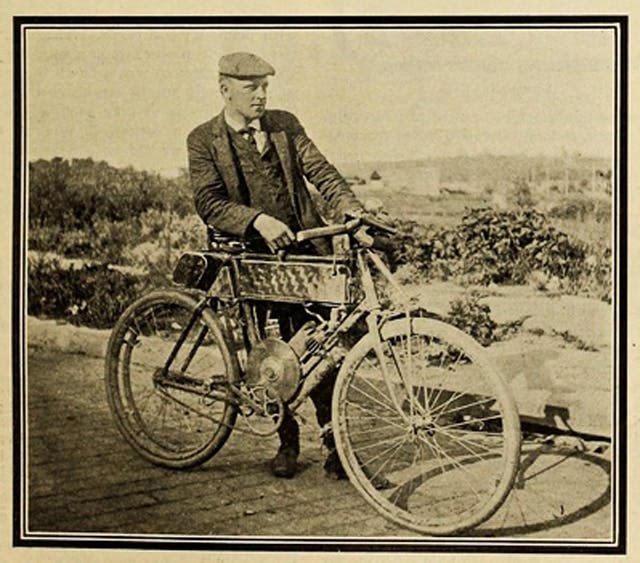

Wyman’s cutting-edge motorized bike—he referred to it as a “motor bicycle”—was powered by a 200cc, 1.25-horsepower, four-stroke engine attached to an ordinary diamond-frame bike, but it required the will and strength of a seasoned cyclist to complete the journey due to breakdowns along the way. According to 365daysofmotoring.com, Wyman’s machine was equipped with 28×1.5-inch tires, wooden rims, a leading-link front suspension fork, a Garford spring saddle, a Duck Brake Company front roller brake, and a 1902-patent Atherton rear coaster brake. A leather belt-drive with a spring-loaded idler pulley connected the engine output shaft directly to the rear wheel.

The California motor bike weighed 80–90 pounds without a rider and was capable of approximately 25 mph—and a range of 75–100 miles—using the 30-octane gasoline of the day. Throttle control was not yet perfected and engine revolutions were mainly controlled by means of a spark timing mechanism. The bike’s wick-type carburetor was “crude,” 365daysofmotoring.com says, consisting of a metal box with internal baffles stuffed with cotton batting. With no float chamber, the rider had to periodically open the gasoline tap to admit fuel into the carburetor.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Considering the distance of the trip, Wyman didn’t bring much gear. When he left Lotta’s Fountain, located at the corner of Market and Kearny streets in San Francisco, on May 16, 1903, Wyman carried warm clothing, money, a water bottle, cans of spare oil and gasoline, a Kodak Vest Pocket camera, a cyclometer (he purchased several more along the way before he gave up trying to keep track of his mileage), bicycle tools and spare parts, and a long-barreled .38 Smith & Wesson revolver, just in case.

From San Francisco, Wyman crossed the Sierra Nevada and rode to Reno, where he woke to snow. In his first-person account published in the inaugural six issues of The Motorcycle Magazine, Wyman described the short weather delay—abbreviated because he ultimately decided not to wait out.

“After a very satisfactory breakfast, I looked about for something to beguile the time away. I was in hard luck because I do not gamble, drink, smoke, or chew. The old-time picturesqueness of Reno has departed, but it is still a town of the West, western, and a man of no habits is at a discount in it. There is plenty of opportunity for drinking and gambling about, but for little else. I killed some time profitably by overhauling my machine, and … concluded to get under way.”

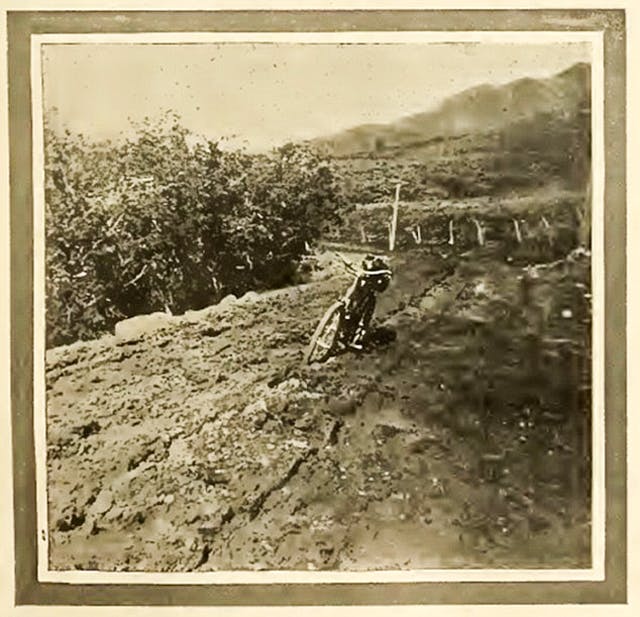

The dirt trails of the day were often impassable, so Wyman rode railroad tracks for more than half the trip—mostly over the ties, which relentlessly pounded both bike and rider. He also took refuge in railroad company housing along the way.

“When mention is made of the places at which I stopped and through which I passed, it must not be imagined that they are all cities, or towns, or villages, or hamlets, or anything in the nature of civilized settlements,” Wyman wrote. “The majority of them are nothing of the sort. They are just places—and it seems a waste of good English to call them that.”

He traveled through the Nevada desert and then through Utah, Wyoming, and into Nebraska. In Omaha, he wrote: “The roughest and most trying part of the country has been crossed, and I have traveled more than 2000 miles of the total distance. I have reached the great waters of the Missouri [River]; the promised land of the East, where I hope to find good roads, lies ahead of me. My anticipations of what lies before me are bright.”

That hopeful spirit carried through Iowa and into Illinois, where he faced his first real mechanical hurdle. Although the bike broke down several times on the western portion of the trip, Wyman’s makeshift repairs kept things moving until he could reach a larger town and perform the work properly. As he neared Aurora, Illinois, however, his engine’s crankshaft snapped, forcing him to pedal the heavy bike 40 miles to Chicago. It took five days for a new crank to arrive by train.

“The motor crank was the last thing that was expected to break,” Wyman wrote. “I had parts of every sort excepting that one along with me, and these were unused, while the one thing I could not replace was the one that broke. This showed that one never can tell what to expect in a cross-country journey of this sort.”

As it turned out, he would need the extra rest (although he hated his time in Chicago and complained that the respite had left him “soft”). After repairing the California and heading east once again, Wyman rolled through Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, then crossed into the state of New York. Then the roof seemed to cave in just before he reached Albany.

“I replaced the belt seven times during the forenoon, and then I spliced it with a new piece at Little Falls,” Wyman wrote. “I was still 40 miles from Albany when my handlebars broke off on one side. I had been there a couple of times before during the trip, and it did not take me long to lash a stick across the steering stem.

“Soon after, the piston began to squeak, and I discovered that the rings on it were worn out. Oil was of no avail, and I rode on with the squeak for company. Six miles from Albany, while I was on the towpath, the rear tire blew out. There was a hole in it that would admit a hand. I walked into Albany. Some of the remarks I made to myself as I walked were not fit for quoting to a Sunday school class. My distance that day was 135 miles. This was to be my last day of big mileage though.”

Forced to pedal the remaining 150 miles to New York City, he missed his goal—by two days—of seeing fireworks there on the Fourth of July. “That last 150 miles down the Hudson from Albany is a part of my trip of which I will always have a vivid recollection. I had seen some hills before, but the motor climbed them for me. In the hills along the Hudson, I had to climb and push the motor along. They seemed steeper than the Rocky Mountains. This I will say, though—from the time I left the Pacific coast I saw no grander scenery than that along the Hudson River. While other sights were not up to expectation, the scenery of the Hudson was far beyond it.”

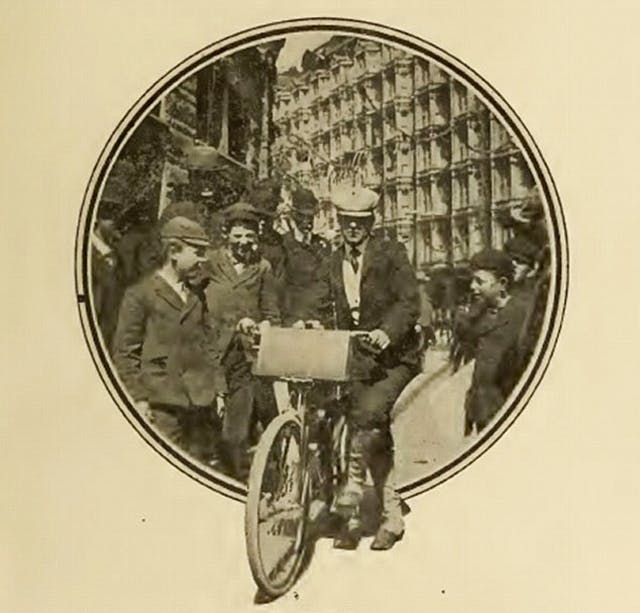

Wyman pedaled all night on July 5 and reached the New York Motor Cycle Club on July 6. While he recovered from the grueling ride, his motorbike was put on display. Before leaving New York, Wyman took part in the inauguration of America’s first nationwide motorcycle organization, the Federation of American Motorcyclists (FAM), his hands still wrapped in bandages from the trip.

Reflecting upon his cross-country travels, Wyman wrote: “While the idea of establishing a record was no part of my purpose, it is worthy of remark that none of the three powerful automobiles that have since crossed the continent have come near to equaling my time.

“With the experience gained and with a more powerful machine—the one I used was of but 1 1/4 horsepower—I feel confident that the journey from ocean to ocean can be made in 30 days without particularly strenuous effort. With a railway attachment, such as is in common use by bicyclists in the West, and which would permit the use of rails across the deserts of Nevada, it will be possible to more than realize the 30 days’ estimate.”

Wyman most certainly enjoyed his train ride back to San Francisco, where his motorbike was placed on display at Golden Gate Park. He spent the rest of his life in California, promoting the Duck Brake Company, serving as a chauffeur, and working as an auto mechanic. He died on November 15, 1959, at the age of 82.

Amazingly enough, Wyman’s cross-country feat was actually the second time he had crossed a continent on a bicycle; in 1900, he traversed Australia on a non-motorized bike. While that ride likely prepared Wyman for the difficulties he would endure on his historic U.S. trip, it didn’t bring him the massive publicity or lasting significance that Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson received. Regardless, nearly 120 years later, we remember Wyman as the OG … on two wheels.