Media | Articles

The first-hand story of the first Mazda Miata

In the early 1980s, Mazda was flush with capital from record sales and already deep in the design process for the next generation of the RX-7. Having proven to the world that it could solve engineering problems that had flummoxed other automotive companies (Wankel’s problematic rotary-engine design, for example), Mazda was confident in its ability to make its flagship sports car a true “world-class” competitor.

Riding all this momentum and strength, the company aimed to move its second-generation RX-7 upward in the market to meet and beat the Porsche 944, with a long-term goal for the third-gen car to surpass the 911’s performance. Mazda’s “stretch goals” were laudable, but the lofty aspirations left a void in the product line just beneath the RX-7—an opening crying out for a great car.

Meanwhile, the longstanding European supply of lightweight sports cars to America had all but shriveled up, leaving its own roadster-shaped void. Whether due to quality issues, labor unions, or America’s ever-restrictive emissions and crash-protection laws, European manufacturers could no longer supply 40,000 small sports cars to American customers annually.

Mazda product planner Bob Hall, a former journalist who fully understood the sports car market, made the suggestion to upper management that the company should develop an entry-level sports car to sit beneath the second-generation RX-7. The advice did not fall on deaf ears. The Porsche 911 had always had a more affordable showroom sibling, an even Toyota had a pseudo sports-car companion for its Supra in the MR2. A younger brother to the RX-7 made sense.

Bob sent a fax to the home office in Japan, inquiring if Mazda could be profitable with a car that sold only 40,000 units per year. The answer was yes, thanks to Mazda’s flexible assembly lines, which allowed a mix of models to be built in one factory (as opposed to GM and Ford practice, where one model supported a whole factory). Hall’s suggestion led to funding for an initial design study.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Every enthusiast employed by a car company has, as a core desire, a wish to create a performance car. No one doodles minivans in their high school notebooks, after all. Mazda’s small team of planners and designers were no different. I was no different. The new Lightweight Sports (LWS) concept, codename project 729, ignited a fire in Mazda’s Southern California Design Studio. I was hired as the first American engineer into a small skunk-works team that Mazda Japan had created to develop products for the U.S. market.

On my first day of work, my supervisor, Shinzo Kubo, asked what I knew about designing a sports car. I had gone to engineering school specifically to learn how to design race cars, and I had by that point owned, restored, and raced about 20 European sports cars, so I told him I might be able help. Since 1979, as a sort of foreshadowing of my own career, I had been marking up RX-7 brochures with a black Sharpie, blacking-out the roof to make the car a convertible and sketching in an open “mouth” at the front bumper. Needless to say, I was very much primed.

Everyone was. Among the stylists were a couple of Art Center graduates and a long legacy of sports car love, ownership, and appreciation. The product-planning department also held people deep in love with racing and sports cars.

Car companies around the world employ sports-car enthusiasts, of course, but at Mazda’s Southern California operation, we reached critical mass, thanks to our own rabid enthusiasm and an upper-management team that truly wanted to be the largest sports-car manufacturer in the world based on sales. (Mazda achieved that title in 1992, thanks mostly to the Miata.)

So we sat around the office’s little white common area and dreamed up specifications for the perfect 1000-kilogram (2200-pound) sports car. Each of us suggested special features that had endeared us to the cars we had owned: We counted over 65 different sports cars in our collective ownership history, from lowly Austin-Healey Sprites and Triumph Spitfires to Lotus Europas, Jaguar E-Types, De Tomaso Vallelungas, and Lamborghini Countaches. With the Mazda project, we had a blank canvas onto which we threw the best characteristics we could think of.

Informing much more than just the shape of the clay model, we were assembling the 729’s soul—trying to make it far more than just an attractive little car. The thing had to drive and race like the best we had known. And that became the engineering department’s job—to fit a capable sports car beneath the design studio’s skin.

The Southern California studio typically hosted visiting designers from Hiroshima. Those individuals would do a few years at our location, then rotate back home. Designer Masao Yagi was on staff when the initial study was commissioned, and he was given a drawing of the rear-wheel-drive GLC econobox chassis layout to work with. He did an exemplary job of draping a sports-car shape over that clunky and upright package, and that gave upper management something to consider.

A fiberglass body was made up from Yagi’s model, and we engaged the English firm International Automotive Design (IAD) to build a running prototype. After the prototype had been shipped back to us, we took it to Santa Barbara to drive around, so executives could view the shape in traffic. That was a key policy at Mazda; the company believed potential new cars should be seen and evaluated in their natural environment, not just in a sterile design studio.

I drove that prototype all around Santa Barbara. People were literally chasing me down to ask about it. At one point, I got stuck at a traffic light beside a Porsche dealership and was nervous about someone taking photos. Looking into the showroom, I saw a few people viewing a 944 on display. One by one, they left the Porsche and came to the window, looking at the prototype, pointing and calling for others to come see.

It was basically an ad-hoc focus group, and we could not have asked for a better demonstration of our concept’s attractiveness to the people who actually buy sports cars. That evening at dinner, R&D director Masataka Matsui said, “Maybe we should build this car.” With that, the “Miata” project was funded for a second clay model.

The styling would be its own challenge, but what lay underneath was critical, what makes a car a car. When an aerospace engineer designs a fighter jet, every part has to contribute to flight. Similarly, we compared every proposed specification for the 729 to the Lightweight Sports Car concept, all while embracing Lotus founder Colin Chapman’s motto of “simplify, then add lightness.”

“We can ditch the ashtray, no one smokes any more, anyway,” suggested planner Jim Kilborne, when we discussed reducing weight. All well and good, but at the time, 22 percent of Americans and more than 50 percent of Japanese men smoked, so the ashtray stayed.

“True sports cars don’t need radios,” Bob Hall offered in a meeting. “We’ll make the engine’s exhaust so melodious, [it’ll be] all you want to hear.” We all nodded in agreement, even though eliminating a sound system wasn’t practical. Such was our laser-focus on making the car enjoyable, light, and sporting.

“The car’s beltline has to be low enough so you can see the asphalt out of your peripheral vision, helping you gauge your speed and see apexes.” That was my suggestion. The idea stuck, and “sensing” the road over the Miata’s door top became a key element in how the car communicates to the driver in a corner.

The fever spread, in the best way, to Mazda’s home office in Hiroshima. Everyone on the project was all in, and the essence of a small, race-capable, high-quality jewel of a sports car became a guiding light. Driven by their own passion, enthusiasts in each department in Japan volunteered their time—often after hours—to work on the 729 project. It was as if we were all in love with the same girl, just without the jealousy.

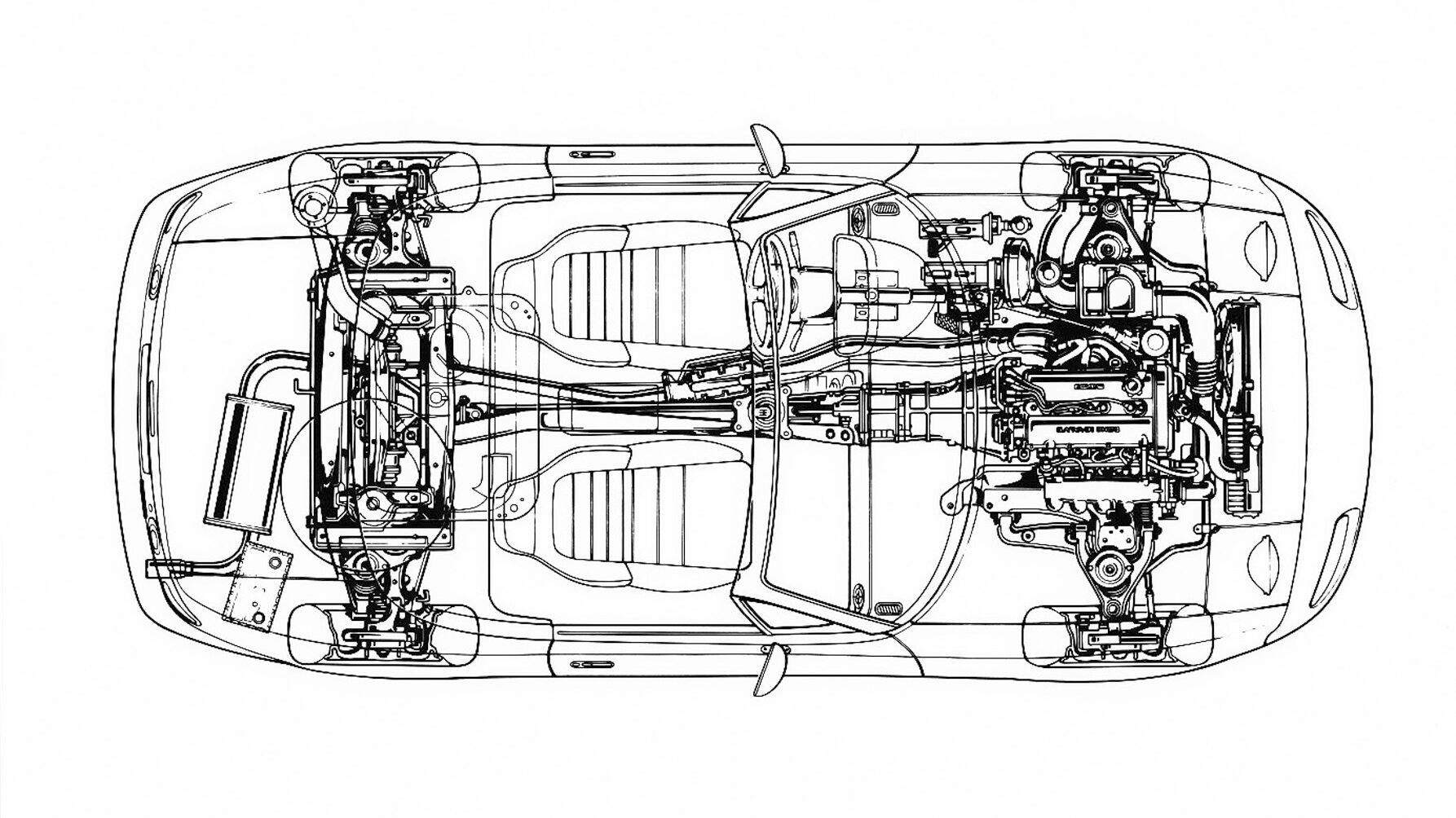

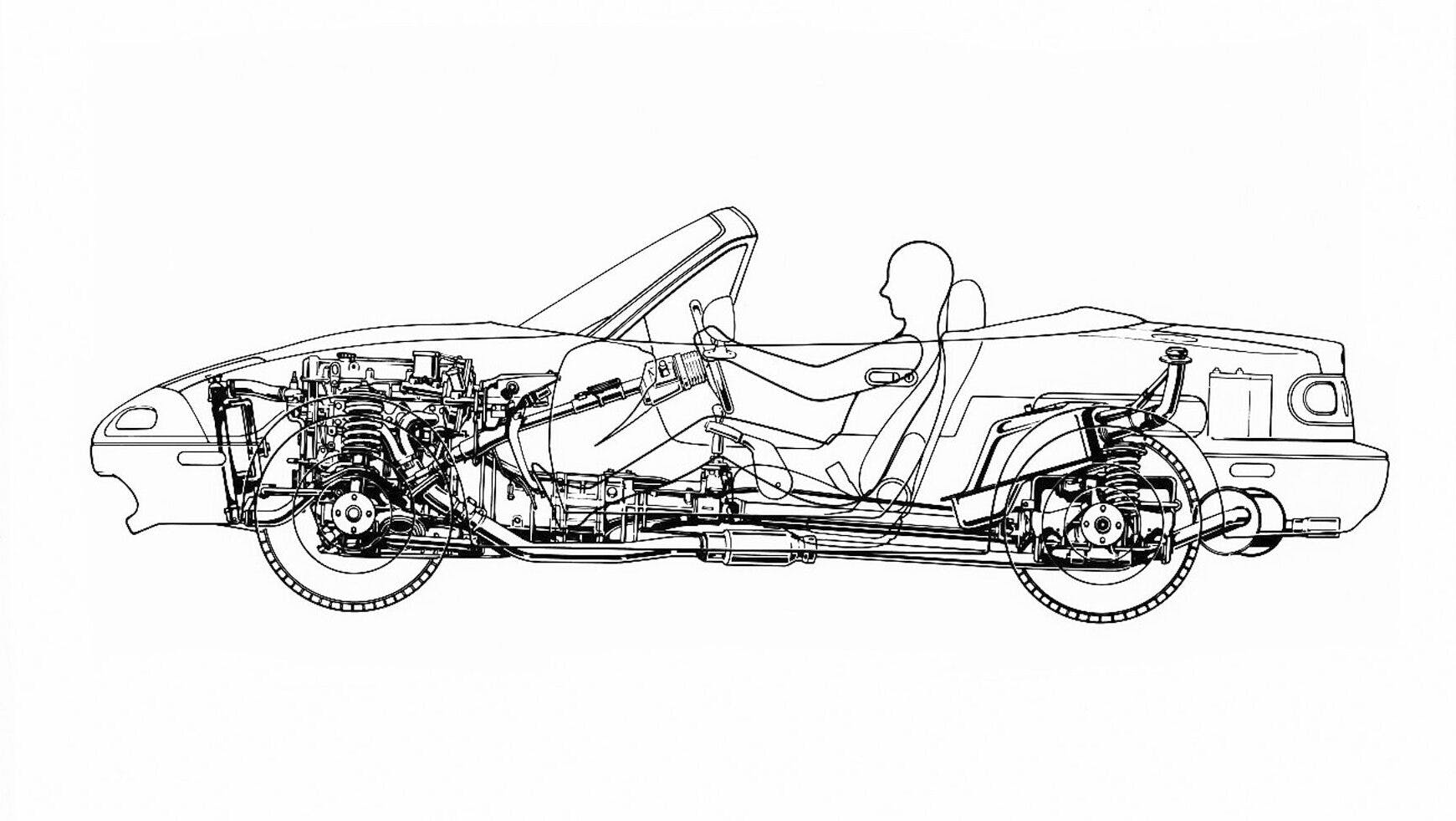

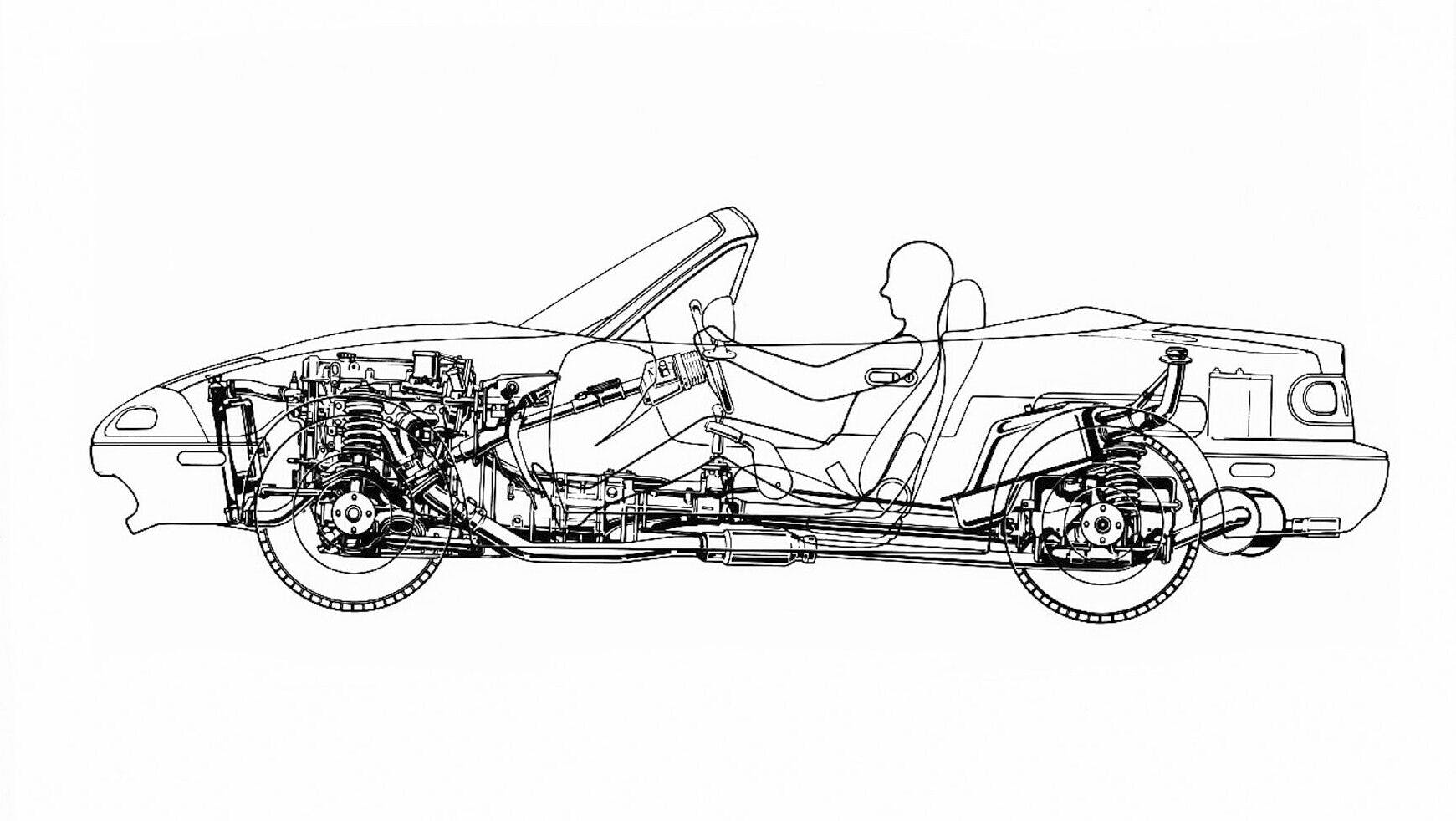

As our work began in earnest, engineering delivered a much more condensed packaging layout for the second clay model—one suitable for a sports car, and that could be easily adapted for club racing. Because no amount of tuning can cover for poor decisions at the packaging and layout stage, we were careful to place the heavy components low and toward the center of the car for balance and weight distribution.

We were dedicated to a front engine/rear-drive (FR) configuration for a number of reasons, the joy of lift-off oversteer among them. We benchmarked the design against cars like the Lotus 7 and Lotus Elan (for driving “feel”), the Porsche 911 cabriolet (for soft-top function and chassis rigidity), and the Triumph Spitfire, MG MGB, and Alfa Romeo Spider (as beloved legacy designs).

Those early design stages held long engineering discussions. Takao Kijima and Jiro Maebayashi, two of the best vehicle-dynamics engineers in the world at the time, kept the focus on optimizing the 729’s handling and grip. As we saw this elegant chassis design come together, the excitement grew. Great credit goes to the late Toshihiko Hirai, who became the car’s program manager and fought so many internal battles at Mazda HQ—first to keep the project alive, and then to find tooling money to construct the special parts required to make the 729 work.

One of these parts the Power Plant Frame (PPF), the long metal brace that ties the Miata’s engine and transmission assembly to its differential. This part was purposefully engineered to allow quick on-off throttle action at 6000 rpm in second gear during full-g cornering without undue drivetrain wind-up—a quality that can kill a car’s controllability during, say, autocrossing or track lapping. I had dug up some details on the torque tube used in the Ferrari Daytona, which performs a similar function, and incorporated it into the design. Hirai found the money in the development and tooling budget to retain this important feature, along with the bespoke double wishbone suspension at each corner, the unique fuel tank tucked in front of the rear wheel’s centerline, and the thousands of other small but special choices baked into the Miata’s character.

People like to compare the Miata to the Lotus Elan. From an engineering standpoint, though, it is more akin to a four-cylinder, nine-tenths-scale Ferrari Daytona.

Back in the studio, Shigenori Fukuda oversaw the stylists working to wrap something attractive over the new chassis layout; Tom Matano, Mark Jordan, and Wu-Huang Chin were sketching like crazy to get our model into shape. Designer Koichi Hayashi was onsite from Mazda Japan to coordinate body design, and we had something on the floor for viewing, analyzing, critiquing, and updating as fast as our modelers could reshape the clay.

This went on for months as the second model became more and more viable. Engineering and design fought over hood lines, door cuts, cowl points, and the usual “hard points,” the points where a car’s guts meet its skin. The body designers had a difficult job, of course, because everyone in the building had an opinion. I had my own and recall reminding the designers that “the tooling costs for a beautiful fender are no higher than for an ugly one, so why don’t you work a little harder on that fender you’ve got there?”

Design of the underpinnings went a little easier. We engineers had only to use the best designs possible for our parts, no human opinion, because math and physics lead to irrefutable conclusions. In the end, the second clay model made a great sports car, but it was not ambitious enough in terms of visual passion, so a third clay model was commissioned. That’s where Chin’s gifts came into play, as the final surfaces were given character and grace.

We shipped the final design package—clay model, engineering drawings, and specifications—over to Japan, where designer Shunji Tanaka tuned up the final body surfaces and developed the interior design. Only then did the very difficult work of designing the nuts and bolts of an actual car begin. Taking a car’s design from concept, even a highly defined one, to reality is always a difficult job, and it often goes awry. But the steadfast Hirai sourced support from key internal departments and protected the fundamental design elements, all of which kept the 729 on track the whole way.

Throughout the duration of the project, there were endless conversations about setting targets and challenging Mazda’s home team to meet them in clever ways. In the transmission department, we had a long talk about shift-rod notch design, chamfer angles, detent-ball spring rates, and synchronizer design, all of which affect a shift lever’s feel.

As I left the meeting, I said, “Just buy a worn-out BMW 7-series with a five-speed and a Jaguar E-type transmission, then blend the feel of those two.” That’s how the Miata’s shifter came out so well.

We also agreed that the soft top had to be able to be closed, one-handed, by an American woman sized in the 50th-percentile, while seated behind the wheel. No one had ever made such a soft top, though the roof on the Alfa Romeo Spider came very close. When Mazda engineers hit that difficult target, they simultaneously created the industry’s best leak-free soft top. For two years, conversations like that went on, and optimization continued, system by system, until finally, the 729 was tooled and ready for testing, including crash tests and final suspension tuning.

In the summer of 1988, U.S.-based product manager Rod Bymaster was casually browsing etymologies in the dictionary when he found the word “miata.” It means “reward” in Old High German, and the name was set. I drove an early production prototype on an autocross course in late ’88 and could not believe how well the dynamics had come together. It drove as well as it looked. Mazda had breathed life into a concept that started as a glimmer in a few fanatics’ eyes just six years earlier. In July 1989, the company filled that void in the market with a masterpiece of a design and execution, the distillation of all the great lightweight sports cars that had come before.

Designed by enthusiasts from around the globe, made by one of the highest-quality engineering and manufacturing companies in the industry, the Miata rolled out and the marketplace rejoiced.

More than one million units later, I guess we got it right. The current Miata MX-5 (ND) carries the same DNA, to the delight of its owners. To be honest, at first, we only wanted to make about a dozen Miatas—just enough so we could each have one for ourselves. I’m glad many of you feel the same way.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

That was a great story about the development of the most popular sports car of all time. Fantastic! I’ve yet to drive a Miata mostly because I just don’t think I’d fit (6’4″, 250) and barely fit in a Boxster (my current quest car). My favorite part was: Colin Chapman’s motto of “simplify, then add lightness.” Cars today, as all powerful as they’ve become (I’m thinking of you, Corvette Z06) are getting way more complex and way to heavy. It would be nice to have more options for something small, fast , and lightweight.

MJ – you probably would have a hard time fitting in one. I’m 6’4″ as well but weigh a bit less. In December 1997, a friend of mine living in Wichita, Kansas, purchased a first-gen Miata in Phoenix, where my friends and I lived. We decided to meet halfway in between in Santa Rosa, NM, and hand off the car to her. We left a few days after Christmas with me behind the wheel. I don’t remember a lot about the trip except that we hit snow somewhere in northern AZ or perhaps in NM somewhere. I had great fun driving that little Rollerskate on I-40 -slipping and sliding around all the semis that were stranded on the highway – but my back hurt!

My friends had driven their parents’ Cadillac Sedan DeVille has the return car and I laid in the backseat of that Cadillac all the way back to Phoenix – moaning and groaning with extreme back pain. That was the first and last time I ever drove a Miata – but I still love the cars.

Norman – is that you front and center in the lead photo?

I am 6 foot and barely fit in a Miata length wise. What’s worse….my head is higher than the roof when closed. With the roof open, my eye level is at the upper frame of the windshield. Too bad.

I’m 6 foot too. 216 pounds. I fit in my 2023 RF club just fine!

Hey MJ, I would recommend that you find someone to let you drive a Miata. I can’t speak to the new ones as far as space is concerned, but I am 6’4″ and haven’t seen 250 in a while. We have enjoyed our red ’91 Miata since early 1992… it had 1,200 miles when we bought it, and it now has more than 200,000 miles. It was my wife’s daily driver for a couple of decades, during which time I drove it from Missouri to NJ in round-about routes four times. We still enjoy afternoon rides to the lake, and it attracts a lot more attention at Cars & Coffee than my Corvette.

I’m your height and only off weight by a few pounds, and I don’t fit comfortably in any generation Miata with the top up, and the driving position puts me looking over the top of the window frame in most of them. I had wanted to get a modern Fiat 124 Spyder, but found out I don’t fit in that either (though I fit just fine in my 1980 124 Spyder 2000).

John, I was just about your size (6’3″ and 250 with a 32″ inseam) when I first sat in an “NC” at the 2005 Texas State Fair auto show, and was surprised how well it fit. I purchased my 2006 MX-5 in April 2007 and still have it. I autocrossed it extensively from the very beginning – I sat with the seat just a few notches forward and reclined the back a few degrees and still just barely fit with the top up and a helmet on. Later I got the factory removeable hard top which gave a bit more headroom. After 15 years and too many modifications to list, it’s a trailer queen that’s still winning SCCA National autocross and time trials events! Find a third-gen car and enjoy!

I own a 2006 2liter MX5 that will scare you in second gear!!!

When I bought my 94 some of the factors that influenced my decision were low insurance rates (surprising) and low maintenance costs. Inexpensive tires, reasonable gas mileage, expected reliability. It was also uncompromised fun with near zero utility, which was a selling point for me. Balance, finesse, road feel, good brakes, visceral and connected. You can’t buy a car like this anymore. Still going strong 29 years later. It is a perfect sports car. I never get tired of articles like this, thank you.

April 2023. Just bought my first Mazda Miata. A faded 99 from Florida. I own 10 cars. All American cars and trucks from 1928 to 2012.. never would I have thought this little car would be the funnest car I’ve ever driven.. we have a t type Buick regal in the mix. And plenty of American horsepower. The size and quite impressive power of the Miata is an absolute blast to drive. If you like cars in the least bit.. you have to drive one of these cars! Then make room for one In your garage.. thank me later ..

A great sport’s car, popular with women, which unfortunately dissuaded insecure man-boys like myself from considering it. I do like the design of the current generation.

My 1990 Miata was a wonderful joy to drive. But, Texas pickups had me breathing fumes at stoplights. Driving behind a pickup, I hit a large log while doing about 70 mph. The front right tire blew and the car went into a number of 360 spins. I came to a stop in the right-side breakdown lane. The outstanding handling of my little Miata saved my life.

Great Article, I thoroughly enjoyed it. Best part was how they came up w/the name.

I still have my 2000 Evolution Orange Miata. Only 644 of these ever came to North America before it was cancelled. Color was a bust. It is garaged kept w/ 75,000 miles, Looks brand new to this day. Great car and so fun to drive, although I’m 60 now and have MS. A tad hard to get in and out of, but oh so worth the struggle.

I own a vintage 1969 MGB Mark II.

Every time you drive a Mazda Miata, please thank ‘Morris Garages’ and ‘British Motor Corporation’ in England for building my car.

-Otherwise- This Mazda would never have been conceptualized.

Bob, I agree with your statement, from a styling standpoint. But Mazda built a sport car that’s more refined and doesn’t breakdown all the time.

Robert: The Triumphs Spitfire, TR-6, and MG Midget (plus Alfa Spider and Fiat 124) crowd might argue with you on that point, but the MGB’s 500k+ sales worldwide certainly helped create the LWS market.

With a hearty nod toward Maranello for creating the Daytona.

The Miata was and is a great sports car. I love the RX-7 “convertible” you sharpied into existence. That would have been an interesting thing.

All that time, effort and money to design what is basically a 500 pound heavier more refined and elegantly appointed Lotus Elan clone, proving that Collin Chapman was a man of vision. Every time that I see a Miata, I remember the ’66 Lotus Elan SE that I owned. It was basic comfort and a blast to drive. That being said, I would buy a Miata today if I were looking for a modern car with a similar updated experience.

I bought a Miata as a Christmas gift for my wife in 1989. The dealership delivered it with a big white ribbon. We lived in northern Indiana and desperately wanted to drive it with the top down.

My wife was a teacher so we she had some time off. I took a week of vacation and we headed to Key West!! Because trunk space was so limited, we left the spare tire at home. Armed with a bottle of Fix-A-Flat, we cringed every time we saw a car on the side of the road with a flat tire. It was unusually cold that winter which kept the top up until we approached Miami. Since it was an early car, we had many people give us a thumbs up and ask about the car. We autocrossed it some and really enjoyed it on many Sunday drives to wherever.

We sold the car after a couple years as something new caught my fancy. During the winter of 2022, we camped in our motorhome at our RV lot in Fort Myers. We tow a Jeep behind the motorhome but I was kinda looking for a second car so we could both go our separate ways if necessary. I perused the Fort Myers Craigslist and found a 1990 Miata for sale that was basically a twin to our car. It was bone stock and red like ours had been. I sent the guy a deposit prior to heading to Florida and we picked it up the day after we arrived. It had original paint that needed only some polishing and waxing to bring it back to life. I had forgotten how wonderful these cars drive. It was great to bring back those memories.

I took the plunge in 2007 (at 74″ tall the NC1 and NC2 were a little tight). The car handles better than the Formula Ford I raced in the early 1970’s. It did wallow somewhat in long, fast turns, and the limited slip diff hooking up caused a distinct change of arc, but a set of stiffer anti-roll bars took car of that. I do wish that Mazda had looked to BMW for wheel arch design, as I’m not a fan of the ‘4×4’ gaps between tires and fenders, but it is a really fun car to drive.

Don’t just call out European labor unions, also call out bloated and unresponsive MANAGEMENT..

My wife and bought our first Miata, 3 years ago. Loved it from the first day. I installed new stiffer sway bars in the front and back, new sway bar links, an engine tune, a cold air intake, wider sport tires. The car is like a rocket on rails. Love throwing it into a corner, and coming out through the apex exactly where I want it to be. We liked it so much, we bought a 2nd Miata, an ND (2018) (First one still in the stable is NC (2008). The refinement of the car 10years newer is amazing! Mazda doesn’t stop improving since the first one hit the roads. Change the oil, put good gas in, change the coolant once every 10yrs – and enjoy for life.

Been loving my ‘93 Miata for 30 years! (with only 50k miles on it)

A wonderful story about a sorely needed, wanted, intelligent sport car. Terrific job, Mr. Garrett, both on crafting a genuine sport car and the above story. My girlfriend has a silver 2001 Miata with tan top, slick original w/ 98,000 miles. Sometimes I drive and despite being 6′ 3″ w/ size 13 shoes, once inside the snug cabin you could drive forever, that happy burble of a stout little engine. Unlike my stick ’02 Civic EX, Miatas have non-interference engines, not that the timing belts prone to failure. Every time I check something on or in it, I’m impressed with its simplicity, quality, thoughtfulness; a beautifully built, even elegant wee barouche.

Anyone can make a big, long car look sleek, elegant. But it takes a master to do so on a short wheelbase.

A real car, a sport car, and i was in the car biz in the late ’70s, sold Fiat, Lancia, MG, Triumph, the first new RX-7, among others; Miatas take their spirit to a higher plane, thanks to nonpareil engineering.

And….the battery’s in the trunk on the passenger side, where it belongs in a well executed, proper sport car.

There’s room enough in the trunk to instill feng shui and “less is more,” more readily than i could in my gal.