Media | Articles

GN34: The fastest Ford the world never saw

It was billed as Ford vs Ferrari: Round Two, with a new Detroit supercar to take on Maranello’s finest. So what happened to GN34, the secret prototype that could have wowed the world? Steve Saxty, a former Ford product designer and author of Secret Fords, takes you inside the hidden world of the canceled supercar.

The Ford GT40 might have crushed Ferrari on the track in the Sixties, but twenty years later Ferrari and Porsche were winning the sales race for highly profitable sports cars—and Ford had no answer.

Or at least, that was the perceived wisdom. Behind the scenes at Ford, a crack team of product planners and engineers were putting their heads together in response to growing numbers of buyers with money to burn on sports cars and luxury models, which were bursting with profit if you played your cards right.

Since the start of the Eighties, Ford had been pondering how it could enter the sports car market with a Ferrari rival costing Corvette money. By the end of October 1983, some of the brightest brains in the company had pulled together a strategic paper that set out the case for a world-class supercar and tackled the thorny issue of how to circumvent the company’s corporate culture that was tuned to conceptualizing and building mass market, everyday cars. At the time, even the Mustang was limping along on just four cylinders.

The Detroit product planners ran the numbers; there was money to be made and an obvious place to start looking for it. They reached out to Ford’s Special Vehicle Operations group (SVO), the performance division ultimately responsible for the turbocharged Mustang SVO. (The department’s equivalent in the U.K. was the British Special Vehicle Engineering group that created the Capri Injection and Sierra Cosworth.) SVO consisted of a 30-strong team of engineers, planners and marketers led by Mike Kranefuss, Ford’s competitions manager who had successfully campaigned the Cologne Capris against the BMW Batmobiles a few years before moving stateside.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Kranefuss was a racer through and through, unused to making road cars, but after his young team created the highly regarded Mustang SVO, it was clear that they could move far faster than Ford’s huge, but lumbering, engineering team. SVO were perfect for the job; an internationally-minded group of Ford mavericks familiar with the external resources necessary to assemble a Ferrari rival sold at a Corvette or Porsche 944 price.

Kranefuss’s 30-strong team, aided by its 46-year-old Chief Engineer Glen Lyall and abetted by 36-year-old Planning/Program Manager Ronald Muccioli leapt at the chance. “For us it was more than a job and another product, it was our dream.” SVO took on the supercar project, now dubbed GN34.

To meet the brief, and create something far greater than Ford’s Corvette, demanded the sophistication of a mid-engined platform and stylish design to mix it with the Italians. Muccioli, and his product planner Tom Smart, identified the two longest-lead areas needed to get the fastest Ford since the GT40 on the road: designing a suitably slinky body and a high-tech, high-performance motor.

Engine choices were limited. SVO visited Lotus to examine teaming up on the next Esprit, but, to nobody’s surprise, Hethel had no defined plans. Within Ford there was the Sierra Cosworth engine, but it was expensive and its harsh four-cylinder turbo would never entice someone from their V-8 Ferrari. Ford’s upcoming modular V-8 engine was promising, but too far off into the future, while externally purchased engines like Porsche’s V-8 were ruled out on grounds of cost. The standout option was Ford’s upcoming Super High Output quad-cam V-6, then being designed with Yamaha for the high-performance Taurus SHO model. Its 3.0-liter capacity could be expanded as needed and its sophisticated design had an appeal of its own in the face of a V-8.

SVO lucked out, and GN34 would use the Yamaha-Ford motor that was—in its day—one of the more advanced V-6 engines around. Only Honda and its V-6 VTEC motor in the later NSX would better Ford’s effort.

Things were going well. SVO had an engine. Now, in spring ’84, Muccioli and Tom Smart turned their attention to the car’s styling, and this was a headache. None of Ford’s factories were geared up to make 20,000 specialist mid-engined cars annually, so they packed their bags and headed to Europe—the home of supercar suppliers and specialist manufacturers.

Heuliez, a French coachbuilder, was keen and even offered some speculative sketches, but once the SVO boys landed in Turin and visited Italdesign, it was clear that they had found a potential partner. Giorgetto Giugiaro’s company could not only style the vehicle but also handle the body engineering necessary to facilitate production by a third party like Heuliez or, their favored option, Chausson in France.

It was perfect timing. The Italians were starting work on an Esprit-like show vehicle called Maya—no doubt hoping to win a Lotus contract to design the British company’s next mid-engined car. In March ’84, Italdesign cannily suggested that perhaps SVO might like to donate a Ford V-6—for a six-figure sum—to power the Maya show car. It was a genius move, for both parties. The Ford-powered Maya jump-started the GN34 project with all the credibility of one of the world’s best designers, while Italdesign won a new client and hopefully a juicy design and body engineering contract.

GN34 was moving so quickly that it was perhaps inevitable that things would veer off the road. In July ’84, SVO presented its initial proposals to Don Petersen, Ford’s CEO, and other senior executives. The product planners had done their sums and calculated a significant profit, but nobody had prepared for the reaction of Stuart Frey, Vice President of Car Product Development. Frey was a Ford lifer and knew full well the risk of engineering a vehicle using external suppliers, especially one targeted at millionaires and sold through Ford dealers. Point-by-point he set out his concerns; warranty, quality, safety, and cost overruns—in his opinion GN34 was too big a risk.

Ronald Muccioli, who was Planning and Program Manager for GN34, recalls the meeting. “Ultimately it was Stuart’s responsibility, and he just did not believe that a handful of car nuts could pull it off when he had an army of engineers.”

Frey dropped his bombshell with chilling accuracy and, to the horror of the SVO team, asked that cheaper options be explored.

The Sierra was the right size; it handled well and was already being sold, with modest success, as the XR4Ti in North America. SVO needed to think fast if it were to protect GN34 from being diluted into a rebodied family sedan. Italdesign, keen to keep SVO’s business, hurriedly built a full-sized foam model using Sierra hard points. But politics were coming into play—surely Ford’s in-house Advanced Design group should design its flagship supercar? SVO couldn’t fight this battle, but it could be smart about winning the war. Muccioli and Smart asked Advanced Design to offer a submission based on a highly-modified Sierra platform that sat the SHO V-6 low in the chassis, as a third option to the mid-engined Maya and Italdesign’s Sierra-derived foam model.

SVO spent five months assembling the three concepts that planner Tom Smart labelled Alternative 1, 2, and 3 along with their relative appeal to three benchmarks: a sporty BMW; a Porsche 944; and finally a Ferrari. The trio of GN34 alternatives—two Sierra-based and the Maya show car—were lined up in December ’84. Against expectations, SVO won the day and was granted its wish to proceed with a mid-engined car to take on the Ferrari 308/328.

However, there was no time for back-slapping. The SVO team was given just 10 months to come back to the board with a finished design for Program Approval—the all-important point in Ford’s design process where cheques start being written for supplier tooling. The program was back on track, but SVO had its work cut out during ’85 if GN34 was to ever reach buyers in ’89.

Italdesign had been contracted to do more than style the car. Now the program was once more proceeding down the mid-engined route, the Italians built a prototype named Maya EM (M for muletto) that resembled a simplified Maya body over more thoroughly engineered mechanicals. Its role was to give a rough approximation of how the car would perform and in September ’85 it was evaluated by Ford’s ultimate test driver, Jackie Stewart, the three-time Formula 1 World Champion.

This could have gone badly, had Stewart been unimpressed by what he encountered and passed his feedback directly to Don Peterson. Yet the news was more than positive: compared to the Porsche 944, Ferrari 308, and Corvette the prototype was more than competitive, not just in speed but comfort—important on rough American roads where the Vette shimmied and shook while the Porsche banged and bounced along the blacktop.

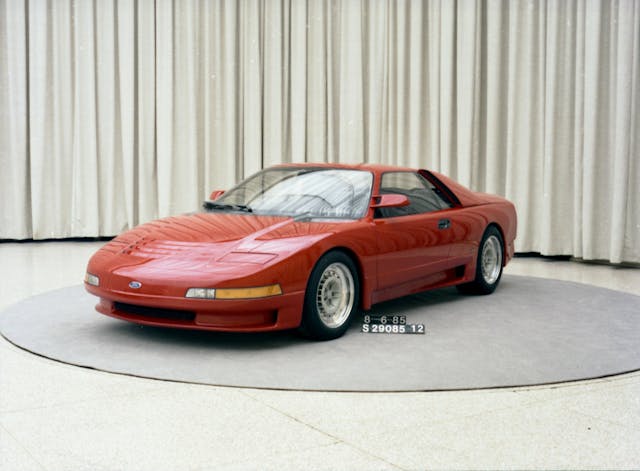

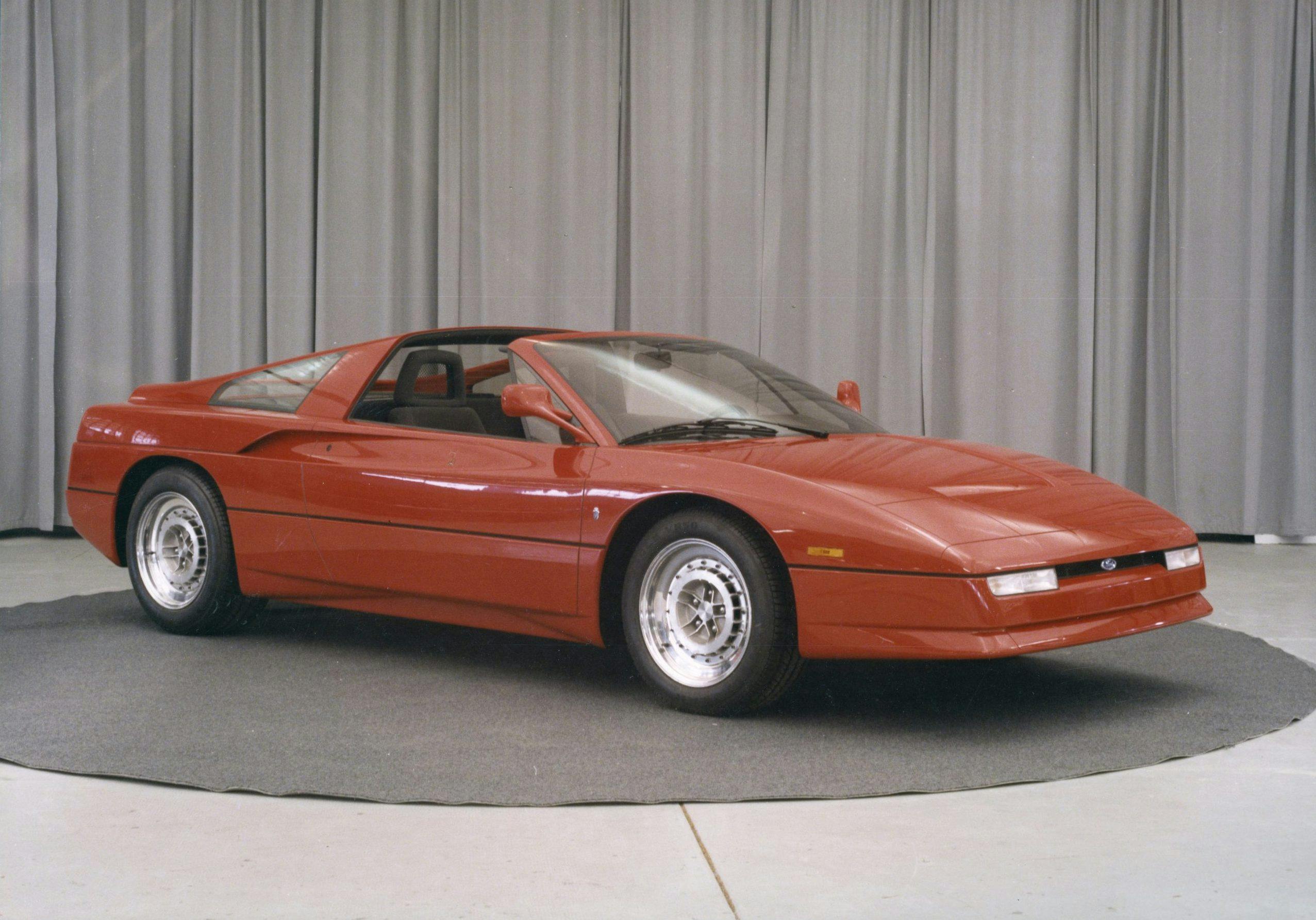

The mechanical layout was well underway, but a bigger battle loomed; what was it to look like? Italdesign built another full-sized model, the Maya II ES (styling) that was far more refined than the earlier Lotus-like Maya show car. The stunning-looking machine featured a sheer-sided Germanic purity of line with the profile of an Italian exotic. But it had competition; the rest of Ford was well-aware of the GN34 project. Ford Design VP Don Kopka instructed the Detroit-based Advanced Design team to offer up a submission and requested another from the Ghia studio in Turin.

Now there were four GN34s; the muletto and the three alternate styling proposals from Italdesign, Ghia, and Advanced Design. The three full-sized models, indistinguishable from a real car, were lined up in Ford’s massive design showroom from which two survivors were selected for market research testing. Italdesign’s Maya II ES design was the one to fall, leaving the Lamborghini-like Detroit proposal to face off against Ghia’s submission that had all the glamour of a Ferrari 308.

Ford’s market research team arranged customer clinics with Ferrari, Corvette, and Porsche owners, in Los Angeles in late ’85. It was a nail-biting moment in the development of the new supercar. If they panned its design, or suggested the pricing was too ambitious, the likelihood was the project would be canned.

Imagine the sighs of relief, then, when word reached the SVO team that the research revealed they adored Ghia’s slinky design and estimated that it would cost the same as a Ferrari. Crucially, even when the secret car’s identity was revealed to be a Ford they still assumed it would be priced above the intended 944/Corvette price point.

Things were looking good, and the project was approved.

More prototypes were made, one an Escort-based mule with a Super High Output (SHO) V-6, plus two modified De Tomaso Panteras built by Jack Roush Engineering using the production-spec chassis designed by Canewdon Consultants in Essex, one with a SHO V-6 and the other a tuned V-8 driving through a ZF transaxle. This most international supercar of all—America-inspired, Italian-styled, powered by Japanese engine technology through a German gearbox and British chassis and assembled in France—was on the brink of production.

But … well, you already knew a “but” was coming, didn’t you? In July ’86 the axe fell on GN34. The American dollar had devalued by 20 percent against the French franc and the car’s profitability was suddenly marginal. A decision had to be made. Ford’s execs needed to choose between a risky supercar sold to tens of thousands—or fund a more Ford-like product that would sell in the millions.

Ironically, it was one of the best-known “car guys” in the industry that would bring about the ultimate demise of GN34. At the time, Bob Lutz headed up the Ford Truck Division in North America and was proposing a four-door Bronco—something his team termed a Sport Utility Vehicle, which promised volume sales. The numbers won and SVO lost. The team’s dream of once again taking the fight to Ferrari was dashed, and Ford’s new Explorer helped Ford ride a wave of profitability through the ’90s.

The accountants ruling Ford’s head said the Explorer was the way to go, but the pony car maker’s heart still pounded for wrestling with the prancing horse. The dream refused to die; Ford took another shot at Ferrari in the mid-2000s with a reprise of the GT40 in modern form. But, unlike GN34, it cost three times as much as a Boxster or Corvette and it was more of a backward-looking GT40 homage than the of-the-moment GN34.

The bullseye that Ford nearly hit—Ferrari appeal at a Corvette price—remains as elusive today as it ever was.

***

Limited quantities of Steve Saxty’s book, Secret Fords, are held in stock in New York to reduce shipping prices. The Volume One and Two author-signed and numbered Compendium Sets can be purchased together for a $14.45 saving using the code 2BOOKSAVE at www.stevesaxty.com

It’s funny, I had always heard that the reason the Taurus SHO existed was because Ford cancelled the supercar project but had already ordered a bunch of engines so they had to put them in something. Also, in order to keep the Mustang guys from canceling the SHO they had to detune the engine from a 300+ hp, 9000 RPM monster to the still impressive 220hp that we got so that the 5L still made more power. It’s interesting to hear that the exact opposite was actually the case, that a cancelled supercar project had actually been planning to borrow the engine from the SHO. Thanks for the history lesson!

Looks like a Fiero and a 300ZX had a baby.

And an ugly baby to boot.

yup

always thought ford should have made an SHO mustang. a SHO Pony

A bit of Ford Probe, 300ZX, it’s very much of it’s time.

And an ugly baby to boot.

I can see the design elements that made it into the 89 Probe

Imagine a rear wheel drive Ford Probe with a mid-engine Yamaha SHO engine making 400hp, revving to 9000rpm and driven through a 6 speed ZF trans in 1989? And selling for Corvette money. THAT would have crushed Corvette sales and still allowed Mustang to hold onto its segment.