Media | Articles

The Citroën DS, a Goddess of Design, Turns 70

“Today, we wouldn’t do it again.”

These words are from Paul Magès, the inventor of the famous Citroën hydropneumatic system, speaking about the DS in a 1985 interview.

Although that may sound overly dismissive, Magès was merely stating a fact. Because the Citroën DS, which turns 70 this year, was indeed the product of unique, unrepeatable circumstances.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Precious few times have any car company’s engineers been granted a similar degree of freedom to pursue their vision for the future of the automobile. A rare luxury that, not too many years later, even Citroën itself would no longer be able to afford.

Work on the VGD (an acronym for Voiture à Grande Diffusion, or “mass-market car”) began in the late 1930s, but the onset of war, of course, quickly put a stop to the proceedings. Once design activity resumed, though, Citroën’s chairman, Pierre-Jules Boulanger, made it clear that nothing was off the table: “Study all the possibilities, including the impossible.” Not that his chief engineer, André Lefèbvre, needed any such encouragement.

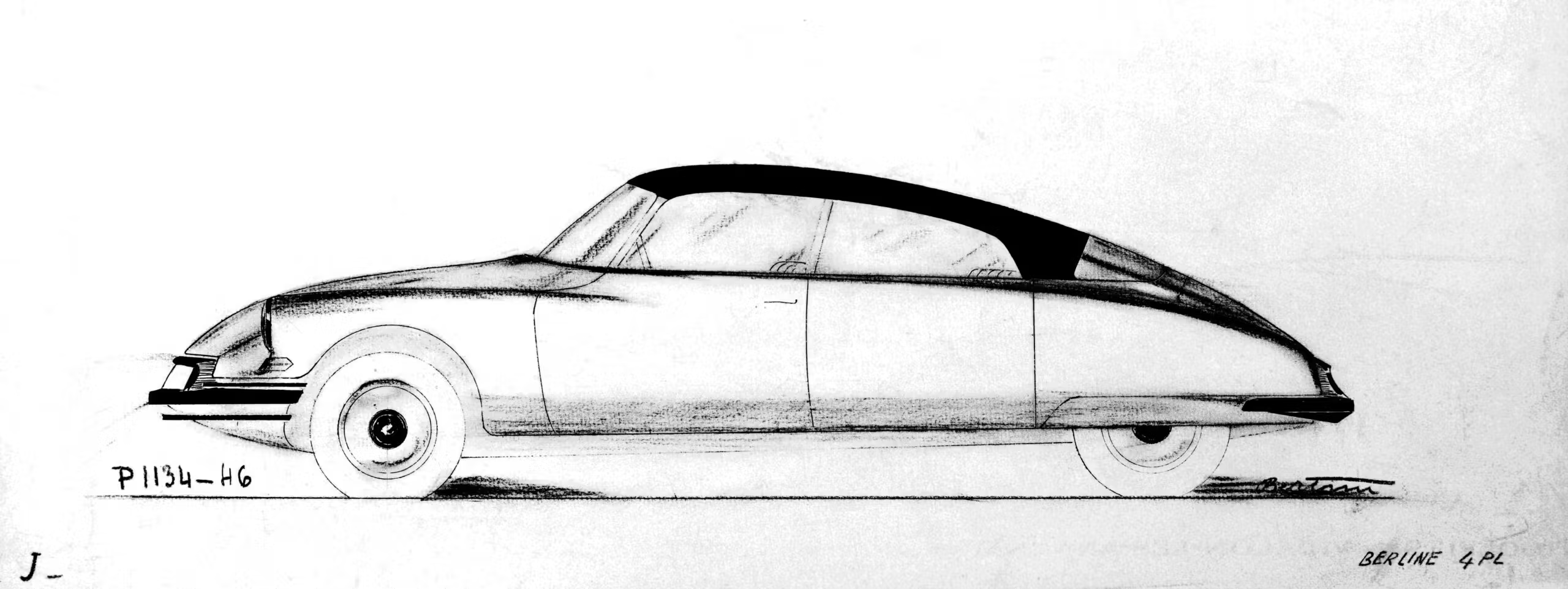

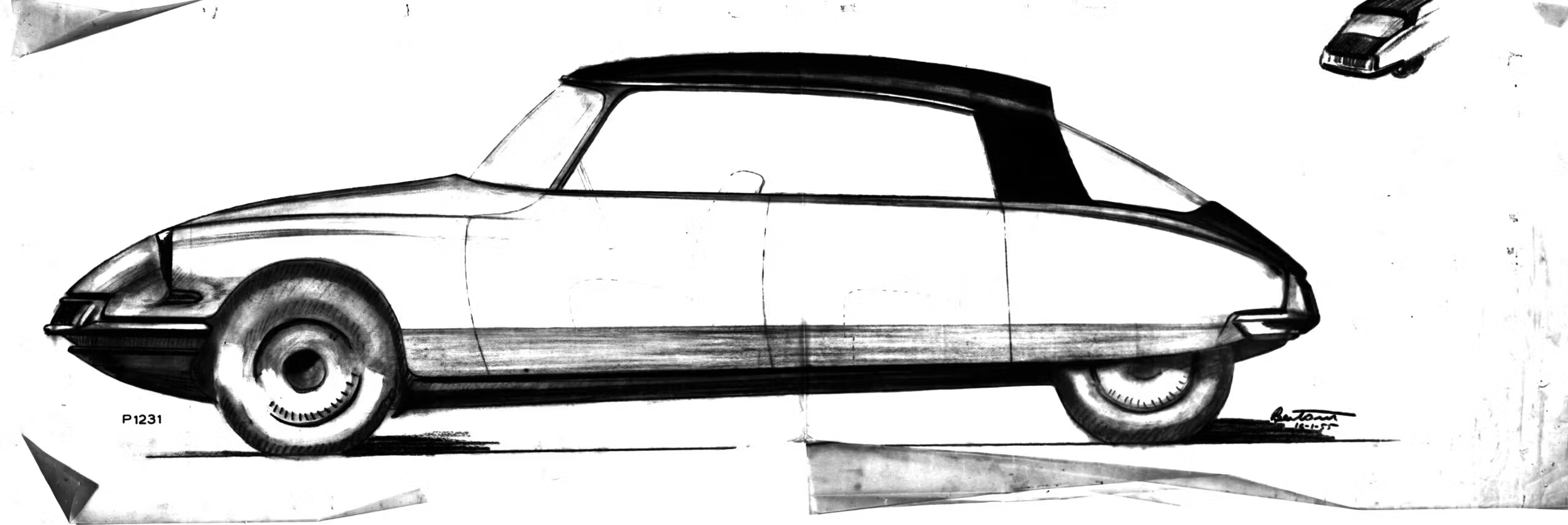

Before joining Citroën to develop the seminal Traction Avant, Lefèbvre cut his teeth under the aviation pioneer Gabriel Voisin, from whom he inherited a distinct taste for the unorthodox. He envisioned the new Citroën for the postwar era as a highly streamlined “teardrop” design and instructed the marque’s resident stylist, the Italian Flaminio Bertoni, accordingly. Streamlining wasn’t a new idea by then, but the DS could very well be considered the definitive take on the “teardrop” concept pioneered by Paul Jaray in the early 1920s.

In his quest to create the perfect aerodynamic shape, Lefèbvre sought to eliminate the classic radiator grille and replace it with an air intake placed below the bumper. This isn’t usually the most celebrated aspect of the DS’s design, yet it has undoubtedly proven the most prescient. Yes, most new cars on sale today still come with a front grille. But that’s a mainly cosmetic affair, while most of the cooling air comes through the intakes placed in the lower bumper area, as pioneered by the DS.

The engine on the DS sat longitudinally behind the front axle, as it did on the Traction and other early front-wheel-drive cars. However, this also plays an essential role in the DS’s exterior design because, coupled with a generous front overhang, it allowed Bertoni to draw the low and swoopy bonnet line that Lefèbvre was after.

By then, front-wheel drive had long become a Citroën hallmark. Still, on the DS, the Marque’s engineers also leveraged it to great effect for aerodynamic purposes, as not having a propshaft meant its underside could be flat and smooth, not unlike those of modern EVs. Even the exhaust silencer box is neatly tucked in a specific recess to avoid disturbance to the airflow under the car.

As the front wheels put power to the ground and carry most of the car’s weight, the rear track could be made significantly narrower (by about 8 inches) than the front without adverse effects on the handling. This helped make the DS one of the few genuine teardrop designs, as its shape tapers toward the rear not only in profile but also in plan view. Furthermore, that rearward taper plays another key aesthetic role on these classic Citroëns, and that’s due to the absence of a rear wheel arch opening. Closing off the rear wheel arches can pay big dividends in aerodynamic terms but rarely “works” as well aesthetically as it does on the DS. And that has a lot to do with that gentle rearward taper, which disguises the length of its unbroken side surfaces when observed from the front three-quarters.

Conceived well before passive safety became a concern, the DS’s unibody structure (which hides under the unstressed, bolt-on outer panels) was designed on engineering-first principles. The steel box sections are thick and strong where the loads are, while the rest of the structure gets leaner and lighter as it rises toward the roof, keeping the center of gravity nice and low. The windscreen pillars, in particular, are barely thicker than a child’s crayon and, together with the frameless side windows, give the driver and passengers a nearly unobstructed view of the road ahead. Just don’t roll it. Although, to be fair, that’d be good advice with any other midcentury classic.

By most accounts, Flaminio Bertoni was never quite satisfied with the DS’s rear end design, which ironically ended up being the area that changed the least during the car’s nearly two decades of production. Throughout the DS’s development, Bertoni’s drawings and models showed a rear-end profile with a continuous, unbroken line from roof to bumper. The marked “step” between the edge of the roof and the rear screen we see instead on the finished car came late in the development process. So late, in fact, that most tooling had already been purchased.

Chances are you’ve never noticed it, though, because Bertoni made sure no one ever would. To divert the eye from what he considered an awkward break in the car’s profile, he placed the indicator lights on the roof’s cant rails, encased in an element that looks vaguely like an ice cream cone. It’s a minor detail, but as a delightfully artful yet eminently rational way to solve a problem, it perfectly represents what makes the DS’s design so special.

Then as now, the Citroën DS looks like nothing else on the road, yet there’s nothing gratuitous or wacky about it. Every aspect of it is there to make it a better car according to a very particular vision of what a car should be. And the DS does so in a way that conveys the optimism of the postwar years, that somewhat naive yet powerful faith in technological progress as a force for good, better than any historical treatise could.

Spectacularly expensive to develop and produce (the hydraulic system’s components required a new, dedicated factory and manufacturing tolerances down to micron levels), the DS took years to make any money for Citroën and, even when it did, the profit margin was often slim and inconsistent. So it comes as no surprise that the rest of the automotive industry gave a long, hard look at the DS and decided to stick to its own path. Sure, Mercedes-Benz and Rolls-Royce licensed Citroën’s tech for their self-leveling suspension systems, while Rover adopted the idea of bolt-on outer panels for the P6 sedan, but that’s about as far as it went.

The DS’s launch in Paris 70 years ago is one of automobile history’s great landmark moments, yet at the same time, it’s arguably proven one of the least influential. Citroën’s greatest gift to the motoring world remains a magnificent outlier, the vanguard of a future that never quite materialized and is, thus, timeless.

And that, of course, is all part of its enduring charm.

***

Matteo Licata received his degree in Transportation Design from Turin’s IED (Istituto Europeo di Design) in 2006. He worked as an automobile designer for about a decade, including a stint in the then-Fiat Group’s Turin design studio, during which his proposal for the interior of the 2010–20 Alfa Romeo Giulietta was selected for production. He next joined Changan’s European design studio in Turin and then EDAG in Barcelona, Spain. Licata currently teaches automobile design history to the Transportation Design bachelor students of IAAD (Istituto di Arte Applicata e Design) in Turin.

The DS really is a fascinating car.

You have the groundbreaking body design, as described in the article, which was considered so avant-garde that it was used as the basis for a “taxi of the future” in Back to the Future 2, to depict what the film makers thought in 1989 (flying) cars would look like in 2015 – not bad for a car from 1955.

There was the hydraulics system, which behaved a little like a mammal’s circulatory system. It powered the trick suspension, giving it incredible ride quality, an adjustable ride height, and the ability to replace a conventional car jack with what was essentially just a rod, making putting the spare tire on easier. The hydraulics also powered the steering. The brakes also benefitted from the green life-blood. Instead of a brake pedal, it was more of a button, requiring very little pressure during a time when most cars still needed a real shove to get them stopped. The gearbox joined in on the hydraulics party; it was a semi-automatic unit with the hydraulics working the clutch and gear linkage.

By the late 60s the DS sported another party trick: headlights which would rotate a bulb inboard when the steering wheel was turned in order to illuminate into turns.

The DS is a fascinating car. I don’t see as many today but as a kid there were a few out there.

Amazing and brave design and engineering!

So, the engine was longitudinal, but it was front-wheel-drive?

How did one change the rear tire?

Another aviation pioneer connected with Gabriel Voisin was Houdini, who flew one of Voisin’s planes in Australia, becoming (purportedly) the first person to fly on that continent.

The rear tire can be changed quite easily, because the rear fender can be removed in a matter of minutes by undoing a single bolt.

Longitudinal front wheel drive actually isn’t that uncommon. Off the top of my head: the Oldsmobile Toronado from the 60s had a big V8 configured that way, Audi did it for decades, and Chrysler’s LH cars – themselves rooted on a Renault design – were common cars that shared the layout.

I owned a ’78 CX when I lived in ‘West’ Berlin in the late ’80’s. The car was a marvel of esoteric engineering down to fittings for the meters of pneumatic lines. Instead of the typical flared fittings, Citroen’s used a ball and socket design. Any breaks or leaks made a trip to the dealer a priority, pneumatic fluid was 20DM a liter. The smoothest ride of any comparable European sedan. I hit a very stable 200kph on the Autobahn. Aircraft tolerances.