Media | Articles

That time Citroën built and tested a helicopter with twin-rotor Wankel power

Carmakers from all over the automotive spectrum are, oddly enough, turning their attention to the flying taxi segment. Porsche, Hyundai, and Cadillac are among the brands that have indicated they hope to plant their stake in this burgeoning niche in the not-too-distant future.

Paris-based Citroën nearly beat them all to the punch during the 1970s, when it developed a helicopter named RE-2 that was small, light, and powered by a Wankel engine.

Competing against well-established names like Bell wasn’t Citroën’s initial goal. The famously quirky French automaker began investing a substantial amount of money into Wankel (rotary engine) technology during the 1960s, notably through a Luxembourg-based joint venture with NSU. The company was named Comotor and, in pursuit of valuable powertrain data, it put a futuristic, Citroën Ami 8-derived prototype (dubbed M35) in the hands of several hundred carefully-selected drivers. Feeling confident, Citroën released an upmarket variant of the GS powered by a twin-rotor engine in 1973, and it planned to offer a range-topping version of the CX (which arrived in 1974 to replace the DS) with a mighty, 160-horsepower triple-rotor engine.

Wankel woes

Citroën’s grandiose plans for the Wankel fell apart after the 1973 oil embargo sent fuel prices on a 30 percent hike. Rotary engines burned more fuel than piston engines, a differentiator that was suddenly rather problematic. It didn’t help that NSU’s Wankel-powered Ro 80 sedan suffered from well-documented reliability and longevity issues that earned rotary technology a bad reputation. Production of the GS Birotor consequently ended after about 846 units were built (most were bought back by the factory and destroyed), and the Wankel-powered CX was shelved mere months before it was scheduled to enter production, forcing engineers to launch the sedan with an updated version of its predecessor’s four-cylinder engine.

Nearly a decade’s worth of research and development were pulverized, and Citroën wasn’t in a position to take the punch. The company entered the 1970s on perilously shaky financial footing, after being all but forced to absorb Panhard in 1965, and its own less-than-wise business decisions—purchasing Maserati, for example—didn’t help the situation. Citroën couldn’t write off the Wankel project and carry on as if nothing had happened. It needed to recoup at least part of its investment.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Up, up, and away

Exactly how Citroën landed on the helicopter segment as the solution to its predicament is unclear. Regardless, the RE-2 project began in 1973. With serious financial trouble on the horizon, the company recruited Charles Marchetti (1916–1991) to reimagine the rotary project. Marchetti was one of the best-known helicopter engineers in France at the time, responsible for creating the brilliantly simple Alouette II released in 1956 (and still used by some countries today).

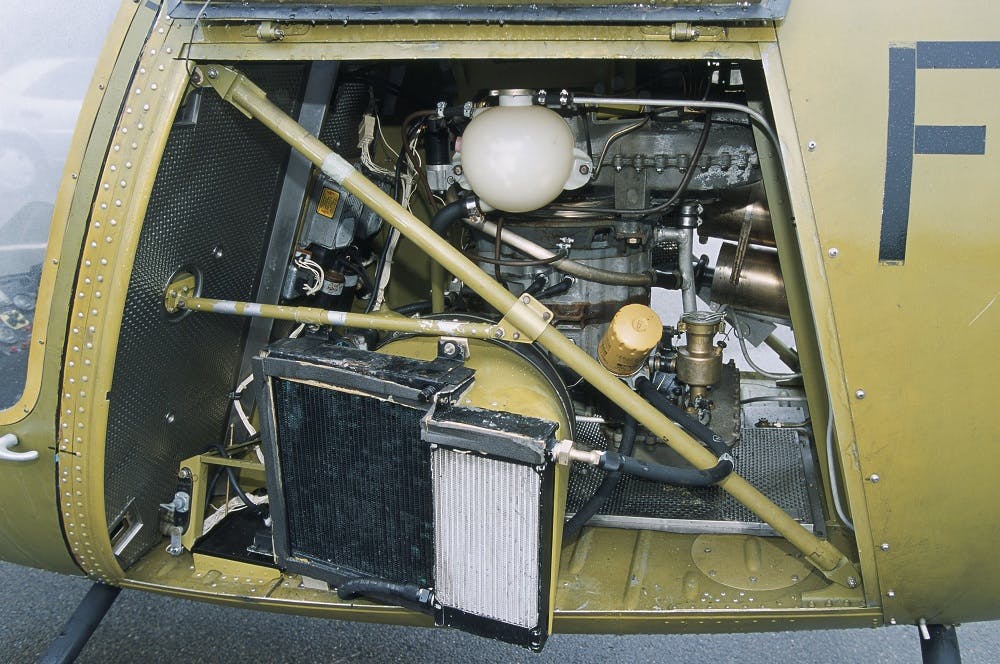

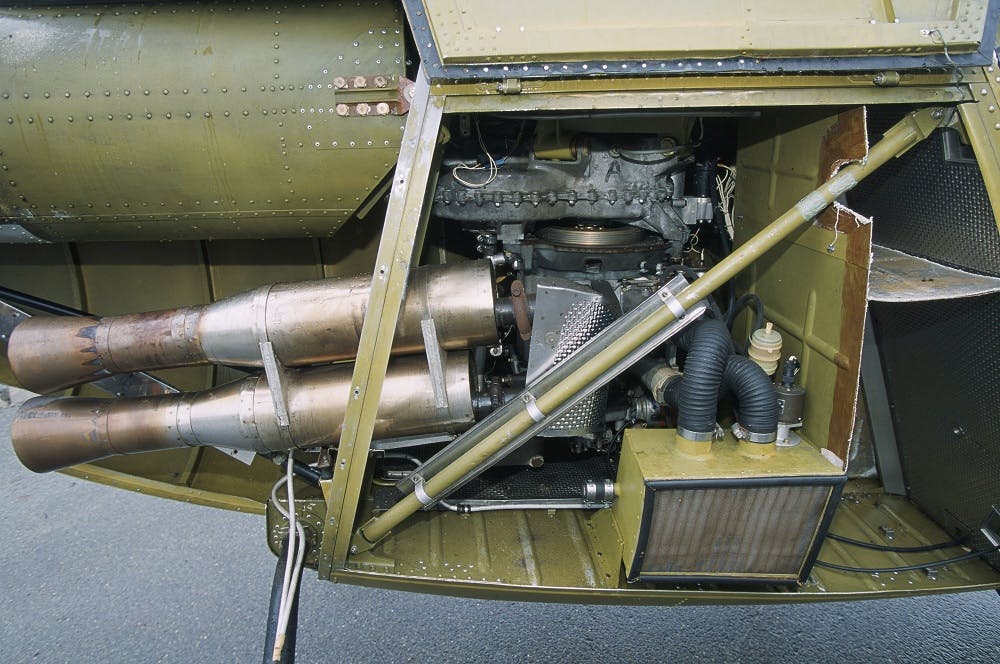

As Marchetti’s team developed the structure, Citroën engineers built a 170-horsepower evolution of the GS Birotor’s Comotor 624 engine with larger rotors. Instead of a Solex carburetor, a fuel injection system was developed in-house. Most likely, swapping the fuel delivery system was a way to keep the RE-2’s gas mileage in check; after all, stopping to fill up on a regular basis was less convenient in the air than on the French autoroute. On paper at least, the helicopter offered a cruising speed of 108 miles per hour and it was capable of reaching 11,482 feet—figures that made it reasonably competitive.

Had Citroën finally found a good use for the rotary engine it painstakingly developed? Theoretically, yes. In practical reality, no one knew, because none of the company’s employees were qualified to test an experimental helicopter. Palpitant!

Professional pilot Dominique Gilles joined the project and fired up the RE-2 for its maiden flight on December 24, 1975. Everything went as planned, and the RE-2 took off and landed without causing a five-alarm catastrophe.

Building a flight-worthy prototype in the space of about two years was a major achievement. None of today’s automakers who dream of shuttling you across New York City’s airspace have reached such a point as of this writing.

With the finish line somewhat unexpectedly in sight, Citroën embarked on the process of homologating the RE-2. Inspectors rigorously put the helicopter through its paces, only to reject it after noticing that the engine tended to overheat at higher revolutions.

Engineers returned to the drawing board. Not obtaining the government’s certification was a setback, but it wasn’t a crippling or demoralizing one, and keeping the twin-rotor’s temperature in check should have been a reasonably simple fix.

Peugeot says non!

Michelin owned Citroën when the RE-2 project was launched, and executives seemed content letting the firm try to put a Wankel in the air while the brand’s lineup aged (the 2CV turned 25 in 1973) and sales eroded. On the brink of a second bankruptcy, in December 1974, Citroën was placed under Peugeot’s stewardship and the two formed PSA Peugeot-Citroën two years later. Executives immediately made it clear that adding helicopter manufacturing to the company’s résumé was not a priority.

Above all, Citroën needed to increase its sales by renewing its automotive product range, and it was ordered to use as many Peugeot parts as possible to leverage the benefits of economies of scale. And yet, somehow, Peugeot initially allowed the Wankel helicopter project to continue. At the time, one of the French manufacturing sector’s greatest source of pride was Aérospatiale, which operates today as Airbus Helicopters. The gloss factor of rivaling one of France’s best-regarded companies was difficult to resist, and Peugeot tentatively allowed the helicopter project to continue long enough for the RE-2 to obtain a six-month operating permit on June 14, 1977. The French Army, it should be noted, had shown a serious interest in placing a lucrative order for the RE-2 if it ever went on sale.

Citroën never obtained the government’s final certification, however, and the French Army instead purchased Aérospatiale’s Gazelle helicopter, which was powered by a turbine. Exasperated, and undoubtedly burdened from having bailed out Chrysler’s European division in 1978, Peugeot canceled the RE-2 project on May 5, 1979.

One prototype was built in the end, and most sources agree that it logged about 38 hours of flight time. Th RE-2 wasn’t crushed, miraculously, and it was restored in the early 1990s. The helicopter then spent decades displayed next to other aborted projects (including a four-wheel-drive tractor) in a vast collection of oddities Citroën keeps on the outskirts of Paris.

Whether or not the Citroën RE-2 should be understood as an inspiration or a warning is up for debate, but our guess is automakers will continue to look to the skies.