Media | Articles

Thanks to W.O.’s acolytes, the original Bentleys boom on

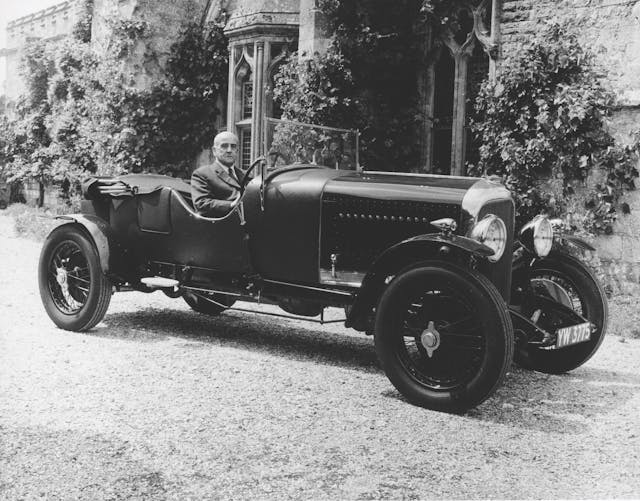

Walter Owen Bentley was well into retirement in the 1950s when members of the Bentley Drivers Club started rallying to his cottage in Surrey, just southwest of London. Unlike some of the other hard-nosed auto chiefs who etched their names into the prows of their own fabulously expensive creations, Bentley was apparently as much a sentimentalist as he was a business failure. He appreciated the visits and was not opposed to celebrating the old days while posing in a driver’s seat for a snap. There’s a photo of him, a slim and balding elder in a raincoat, sitting in his first production car, a 1921 3 Litre, which bore the winged badge of the company he founded when he was 31. “As the last booming Bentley exhaust note faded away,” W.O. wrote in his memoir, published in 1958, “I felt it had all been worthwhile.”

Worthwhile indeed, for his Bentleys have not faded away and are still booming around the world as owners continue to operate those first cars to wear the flying B. A subsidiary of the Volkswagen Group continues to build new Bentleys (and even a few re-created old Bentleys) at the former Rolls-Royce plant in Crewe in northern England, but it is the earliest cars that concern us here. These are the so-called “W.O.s,” produced from 1921 to 1931 at Bentley’s original Cricklewood factory in northwest London. And particularly of interest are the owners who drive them to a degree barely matched by any group of vehicles that can claim its youngest member is 90 years old.

“I’m probably one of the only guys who polishes his Bentley,” says Craig Ekberg, the Southern California owner of a 1928 4 ½ Litre with a reproduction Le Mans body as well as the organizer of several Bentley rallies. “Most of them are left filthy because they’re driven so much.” Of course, the international Bugatti clubs can pull together a sizable group on occasion, and rallies of old Ferraris often snarl traffic for miles. Although W.O.s are smaller in number—only 3034 cars were built at Cricklewood and not all of them survived—their owners seem to enjoy flogging their cantankerous machines, with their suggestive brakes and antediluvian crash-box transmissions, to a degree that is exceptional in the classic car world.

“I’ve driven faster cars and cars with better chassis,” says Paul Lee, a Brit based in Los Angeles who regularly runs errands in his 1923 3 Litre TT Replica. “But this is the most beguiling car I own. They are from the booming 1920s, and you can sense in these cars that sort of optimism and boundless ambition of the times.”

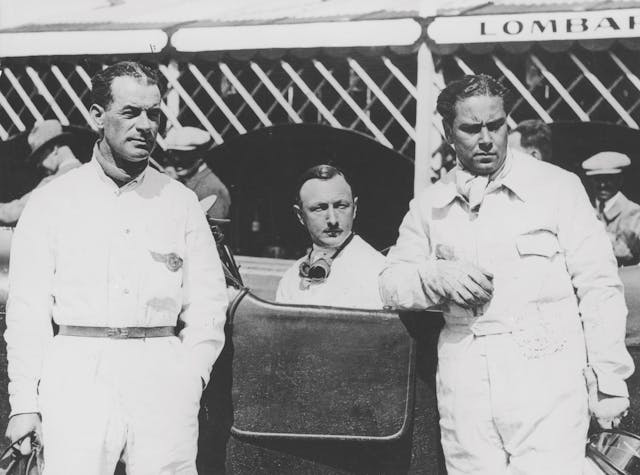

No doubt. The appeal of a Bentley rests partly in that association with the golden age of la belle vie. The company’s annals have now grown to a full century, but they are the richest in the earliest years, during the era of “The Bentley Boys,” the wealthy amateurs who raced for Bentley and lived and played as hard as they drove. Among them, Jack Barclay, the Brooklands racer and car salesman whose Bentley dealership still stands in west London’s Mayfair district; Sir Henry Ralph Stanley “Tim” Birkin, the northern England scion of a fabric lace empire who stuck superchargers on his racing Bentleys, much to W.O.’s dismay; and Captain Woolf “Babe” Barnato, the son of a South African gold and diamond baron who loved Bentleys so much that he shoveled in more than £100,000 of his inheritance in a vain effort to keep Bentley independent. Indeed, not all the Bentley Boys were boys; wealthy heiress Dorothy Wyndham Paget, a descendant of cotton-gin inventor Eli Whitney, was a racing patron and Birkin’s bankroller.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Their stories are ridiculously romantic. There was Barnato pounding through the darkness, rain, and fog in his Speed Six to beat the Blue Train back to Calais from the Côte d’Azur. He arrived at the French port with such a lead that he had time to sail the Channel, roar on to London, and be bounding up the steps of the Conservative Club on St. James’s Street as Le Train Bleu was pulling into Calais. There was the 4 ½ Litre the boys nicknamed “Mother Gun” that was leading at Le Mans in 1927 when it was involved in the famous White House Crash that took out Bentley’s entire team plus four other cars. After the crash, the eminent bacteriologist and part-time Bentley Boy, Dudley Benjafield, helped knock back together the slower 3 Litre they called “Old No. 7” and limp it to victory with the brakes failing, the front axle dislocated rearward from the crash, and one headlight smashed. At the riotous celebration back in London, the team stripped off the fenders and just barely squeezed Old No. 7 through the front doors of the Savoy Hotel so that it suddenly appeared in the dining room with its engine roaring and its single working headlight blazing in pirate defiance. Cheers erupted and the Champagne flowed.

Well, who wouldn’t want to be a latter-day Bentley Boy? Sure, there are no continents left to conquer, and the fire marshal will want a word if you try to run a race car through a hotel dining room (the Savoy’s staff couldn’t complain—Mrs. Benjafield’s family owned the place). But threading a line of ancient Bentleys through today’s traffic requires its own kind of bravado and appetite for adventure. And that do-or-die imperative, that pirate spirit, is as pervasive on Bentley tours today as it is integral to the whole Bentley mystique. Just as in the pits of the long-ago “Double Twelve” races at Le Mans, heroic all-nighters sometimes happen in the parking lots of hotels in order to keep what Ettore Bugatti called “le camion plus vite du monde,” the fastest lorries in the world, running to the finish.

“You have to be a little bit handy,” acknowledged Gary Hunter, who owns the 1929 4 ½ Litre Vanden Plas pictured on these pages, “but there is a lot of pride in being able to drive it and drive it well.”

Here, we should take a moment to add to Bentley’s roster of well-known luminaries the name of Gerald Keston Pelmore (the best British names have more than two handles). “Pelmore” was actually “Pfliederer” back in 1915 when Gerald was still a boy, Europe was at war, and the family fled Germany for England, Anglicizing their name on arrival for obvious reasons. He became a professional photographer by trade and a car enthusiast by passion, and, in 1936, he walked the parking lot at the Brooklands circuit leaving cards on the windscreens of the Bentleys. The cards invited those interested in the formation of a new “Bentley Drivers Club” to phone him at Kensington 7020, his number under the old London phone exchanges.

The first summit in March 1936 was so well attended, Pelmore said later, “that it was necessary to telephone The Bolton hotel at 326 Earls Court Road and ask them if they could provide us with a larger room in which to continue the meeting.” The Bolton is still there, and the Bentley Drivers Club has thrived into the 21st century, but Pelmore did not live to see his creation flower. Two days after Christmas in 1941, his Vickers Wellington bomber went down over Düsseldorf, Germany, returning this native son to his home soil in the most tragic of ironies.

By then, Bentley Motors Ltd. was long gone, too—or, at least, W.O.’s original company. To save money, Bentley quit racing in 1930, giving the press the unlikely excuse that “there is little more to learn either in speed or in respect to reliability at the present moment.” Ultimately, however, it succumbed to both the worldwide economic depression and Barnato’s impatience with being bled white. When Bentley’s prodigious debt was called in by the creditors, it all collapsed, and the firm was bought out of receivership by Rolls-Royce in 1931.

For connoisseurs of the original Cricklewood cars, Bentley’s story largely ends there. But the tale of those old W.O.s certainly hasn’t ended. That’s due to the efforts of the Bentley Drivers Club, which hosts worldwide driving tours and connects owners with each other and with parts suppliers. It’s also due to the tireless work of individuals such as Ekberg who organize and plan their own tours. Original Bentleys continue to rack up miles in far-flung locales such as South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, India, Singapore, Patagonia, and California, not to mention all the kingdoms and republics of Europe.

Ekberg got hooked while on a vintage rally years ago that ran from Seattle down to the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. “My wife and I were driving this old Packard through the rain, the top is leaking and we’re freezing, and I look over and there was this guy in a Bentley, top down, windscreen down, just out there in the weather, and it stuck in my mind how cool it was.”

Ekberg owned several blue-chip exotics, including a Ferrari F40, before branching out into older, slower, and more esoteric vehicles. After a lengthy search, he ended up buying a nearly identical Bentley to the one he saw, with some of the same unusual features, including Zeiss headlights, the longer hood from the low-volume 6 ½ Litre, and the rare factory belly pan. His tours are all 1000-plus miles, but they promise excellent food, high-class accommodation, and even a private air show (an avid pilot, Ekberg is the leader of a band of amateur fighter jocks called the Tiger Squadron). The Bentley tours typically are full at 25 or so cars—any more makes restaurant and hotel bookings difficult—and they are “more work than you know,” he says. But he insists that they pay back richly in fun and fellowship. “It’s a great group, and everyone has a good time being together and enjoying the cars.”

Thanks to the pandemic, the Bentley social calendar has been exceptionally quiet the past 15 months, but we managed to pull together three local cars from the Los Angeles area for a run and a photo session in the mountains behind glittering, beachside Malibu. Three invitations were issued, and three affirmatives immediately came back. After months of downtime, the modern-day Bentley Boys were clearly ready to exercise their cars again.

Ekberg figures there are a few reasons Bentley owners turn out in such strong numbers. “These cars were very sophisticated for their day. They can go 80 mph on the freeway like nothing, which is unusual for a car of that period.” That makes modern touring necessities such as freeway transits much easier and safer. Additionally, he says, they are built like they were designed by a man who got his start in the railroad business (a young W.O. Bentley apprenticed in the locomotive workshops of the Great Northern Railway in Doncaster, England). “They are pretty tough,” he says.

In their homeland, the big Bentleys—despite their lofty values—are regulars at vintage trialing events, a winter pastime involving climbing mud-slicked forest tracks up sodden hills as the muck slings everywhere. They are also seen at another peculiarly English form of motorsport: stubble racing. In a tradition that is thought to date back to the 1930s, after the fall harvest, racing enthusiasts cut dirt tracks through the field stubble. “The surface is dusty and rutted, rather like the roads would have been when the cars were first built in the 1920s.” So says Nigel Batchelor, who owns three prewar Bentleys and is a past chairman of the Benjafields Racing Club. In addition to organizing stubble races, the club has held 500-mile races, 12- and 24-hour races for classic Bentleys, and, in 2019, a race for 40 cars at the Silverstone Circuit with a Le Mans–style running start.

“People ask why we would subject the cars to this sort of treatment,” says Batchelor. “The answer really lies in that spirit of camaraderie that was the hallmark of the original Bentley Boys in the 1920s. The cars were designed for all conditions and have no problem coping with the bumpy fields.”

You can see why Ekberg’s car is one of the few old Bentleys that gets a regular washing. And why Bentley owners think nothing of driving across Tanzania or China in their cars. Batchelor has rallied his cars in Jordan and Iceland and driven in the Le Mans Classic and at Laguna Seca. Obviously, one reason these cars are so valuable is that they are welcomed at pretty much any event where something cool is happening.

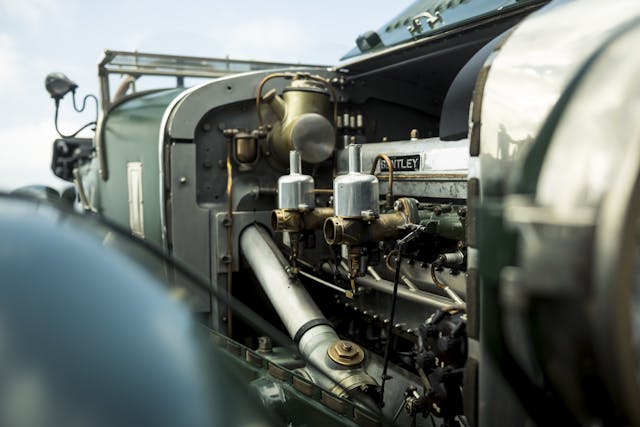

Though Bentley and Rolls-Royce are often equated together (the two companies were conjoined for 67 years), the sportier image Bentley enjoys today has roots in those early years. Compared to contemporary Rolls-Royces—owner Gary Hunter tours in his 1911 and 1923 Ghosts, as well—the W.O. is “the Bugatti Veyron of its day,” he says. The four-cylinder engine in his ’29 4 ½ Litre has an overhead cam actuating four valves per cylinder, four individual ports per cylinder, dual magnetos, and twin spark plugs. Unlike the side-valve six-cylinder Ghost that wafts along smoothly and quietly, the Bentley is feral, a roaring brute built to go fast and do it all night long through the rain and spray at Le Mans.

Not to mention, the Bentley starts a conversation wherever it goes. Says Hunter: “A lot of the cars we have, people go, ‘It’s a what??’” Hunter collects Brass Era antiques and especially early Popes, a largely forgotten though significant name from the earliest days of the automobile. “Nobody knows what a Pope is even though they owned the patent on the automobile and were a very important company,” he says. “But everyone knows what a Bentley is.”

Despite the prestigious badge, these big old Bentleys with their giant headlights, side-slung spare tires, and slightly scruffy appearance come across as friendly and approachable. That matters to owner Paul Lee, who says that for the same money as a 1920s Bentley, “you can drive a modern supercar and everyone will look at you—but they won’t particularly like you. However, you drive up in one of these and people gather around and want to talk to you.”

And Lee echoes the sentiment of other owners in describing the joy of mastering such a demanding car in an age of digital push-button transportation. “There is something way more satisfying about properly changing the gears of a 1920s crash box than going naught to 60 in a few seconds,” he says. “This is like riding a steel horse into battle.”

Indeed, it doesn’t take but a few miles in a car that is older than the Empire State Building to realize that the experience is rather different. The wheel of all W.O.s is on the right, British-style, unless the car was converted. The occupants sit about as high as those in a Chevy Tahoe, and the helm is about the size of a pizza pan to give the driver enough leverage to turn the huge wheels. The short shifter for the non-synchro four-speed is not in the middle of the cockpit but down around your right calf. It takes a practiced finesse to work it smoothly through the gears (owner’s manuals for the early 3 Litre cars advised that “an appreciable pause must be made in neutral in order to get a silent change.”) The foot pedal for the brakes will eventually slow this hurtling 3000-pound ingot of British pride, but experienced drivers keep their right hand at the ready in case they have to reach suddenly for the exterior handbrake that works the rear drums.

That about wraps up the commonalities among the early Bentleys, as every car is otherwise quite different. That is due in part to the fact that although many of the early W.O.s have been converted in later years to sporting coachwork, they all received different bodies at the time from the various coachbuilders that Bentley buyers relied upon, including James Young, H.J. Mulliner, Vanden Plas, and J. Gurney Nutting. There were several different rakes built into the steering column, varying lever lengths and placements, and an endless variety of seats, cockpit controls, headlights, windscreens, dash instruments, fuel tanks, exhaust pipes (fishtail exhausts were on racing cars), and luggage compartments.

“The cars were often custom-fit to the original buyer,” warns Hunter. “For any car you want to buy, it’s very important to sit in it and drive it to make sure that you fit and you can reach the shifter and the handbrake.”

There were several engines that today determine value and desirability, starting with the more common four-cylinder units in the 3 Litre and 4 ½ Litre, and topping out with the much rarer—fewer than 650 made—six-cylinder engines of the 6 ½ Litre and 8 Litre. W.O. showed his fondness for locomotives when he designed the latter sixes with an overhead cam driven by twin reciprocating pushrods, just as the drive wheels of a train engine would be. Besides the top-of-the-line 8 Litre, Bentley’s answer to his arch-nemesis Rolls-Royce, the 4 ½ Litre is the most sought-after, as they were raced with the most success at Le Mans.

Today, many people refer to these old Bentleys universally as “Blowers,” but in fact, only 55 of the original Cricklewood cars were fitted with the Roots-type Amherst Villiers supercharger, five of which were raced but without much success. Famously, W.O. hated supercharging. “To supercharge a Bentley engine was to pervert its design and corrupt its performance,” he grumped later in life.

W.O. Bentley’s story is filled with disappointment, such that upon the publication of his memoir, The Manchester Guardian newspaper commented that “one lays down the book with a feeling of exasperated sadness.” Bentley was in command of his ship for a mere 10 years—actually less, considering that he was forced to make Woolf Barnato director in order to tap Barnato’s cash supply. Bentley was a dreamer and a perfectionist but not an especially astute businessman; the company was deep into the red well before the 1929 Wall Street crash, and the subsequent global depression finally flushed the remaining wreckage of Bentley’s dream into the pocket of Rolls-Royce.

But what a legacy he left for those who want to taste life as a Bentley Boy, who crave a thrilling counterpoint to the bland predictability of the modern era. We can’t go back in time (yet) and experience the gilded, unfettered age these cars were born into. But a lucky few can drive the exact machines that the boys drove. And thanks to a plethora of tour choices, they can do so in the manner in which the cars were engineered to be used. The original Bentley Motors was the brightest of lights that burned for the briefest of moments. But surely, as W.O. observed himself—and his latter-day acolytes would undoubtedly agree—it was all worth it.

This feature originally ran in the Hagerty print magazine RADIUS, a perk of one of our exclusive member programs.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.