Media | Articles

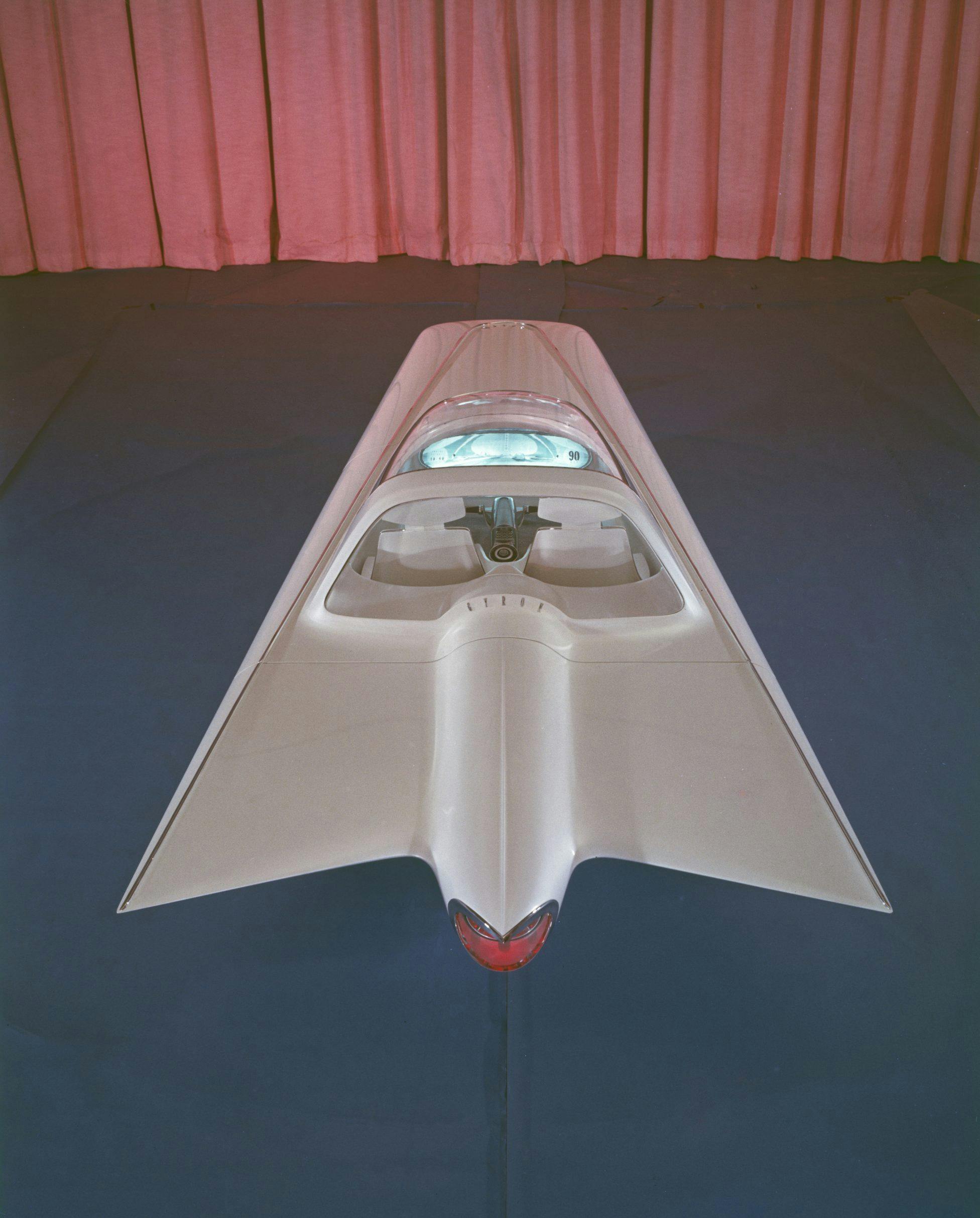

Syd Mead’s Sentinel II thrills and excites now as it did in 1987

Recently I stumbled on a used book online that I hadn’t seen since I was a kid, a collection of illustrations by the industrial designer and futurist Syd Mead called Sentinel II. Ten-year-old me bicycled over and over to a bookstore at the mall to flip through its color-saturated images of cars and machines and cityscapes of tomorrow. The store owner eventually bade me to buy it or stop dog-earing the pages. I should have, because four decades later, the book is long out of print and really expensive. I closed my eyes and clicked.

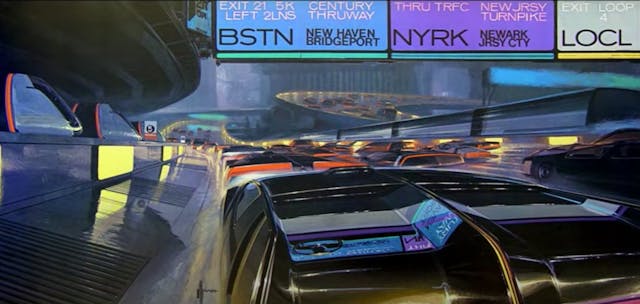

Mead started as a Ford designer. If you own a ’62 Falcon, then you own a Mead original: the afterburner taillights. Around then, U.S. Steel commissioned him to illustrate a book extolling the role of ferrous metal in the coming Space Age. Perhaps the company worried that the clock was winding down on its heavy, rust-prone product, but the moonlighting Mead went to town. He painted levitating (steel) sportsters gliding up to glistening (steel) spires as tanned and fit futurelings held the reins to exotic alien pets while kibbitzing, probably about the many wonders of steel. My favorite image, then as now, is of a rain-soaked New Jersey Turnpike of tomorrow, waist-high iridescent wedges coursing through the gloom and spray beneath lit signs advertising exits for “BSTN” and “NYRK.” It’s such an ordinary scene—but from a dreamy, hypersonic future.

The commission changed Mead’s life, and he soon quit Ford to make a full-time job out of envisioning what he saw as humanity’s inevitable arc of progress. I met Mead shortly after I moved to Los Angeles in 2004, at a vintage dress-up party in an old rail car at Union Station. For a guy known for looking forward, he was strangely attired in a pinstriped mobster suit and white fedora. He gamely pressed a business card into my hand when I asked if he would sit down for an interview. Sometime later, I was invited to his low, midcentury house in the hills above Pasadena, which was lined with wall-size murals of his own paintings and knickknacks from his design work on sci-fi films such as Blade Runner and Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Mead was charming and immensely quotable. He explained that he drew not just vehicles but whole “immersive scenarios” in which the car, the city, the people, the striped catlike creatures, and the mysteriously levitating glowing cubes all had a story. “It’s an underground polar launch facility,” he would say, or, “They’re arriving at the local time portal for a party.” Mead liked to paint arrival scenes, echoing the car ads of the 1960s, but he sprinkled in fantastical elements such as people in ballistic suits admiring their towering, genetically modified racehorses. Sometimes the people were modified, too.

The book’s preface, written in the late ’70s, describes Mead as a “visualizer of the American Dream,” and states that the year 2000 was his reference point—which seems quaint today considering that back in 2000, you could still buy a car with roll-up windows. But it’s easy to forgive Mead for his overly optimistic timelines. For one thing, as he says, he did much of the work in the Sentinel series in the 1960s, a “time of exuberance” for technology and its rapid advancement. It certainly looked like the hereafter we all hope for, everything new and streamlined and scrubbed clean. And it shows how our view of the future is heavily shaded by the mood of the present.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Nowadays, Mead’s visions seem slightly anachronistic given the negativity that prevails, and it’s impossible to flip through the book with the same gobsmacked wonderment. Being an adult does that to you, chokes your brain with weeds of cynicism and inserts the word “but” into all your sentences. However, Mead, who died in 2019 at the age of 86, didn’t seem to suffer that malady. “I am an optimist as an intellectual insistence,” he told me in a quote I will take to my grave. “To be otherwise plays into the ignorant purview of those who still think that medieval life was glamorous.” Meaning that the past was a lot worse than is often remembered or depicted, and we can’t go back anyway.