Media | Articles

Studebaker Lived Large: Two Giant Cars and a Living Sign You Can Still See From Space

We associate the name Studebaker with cars and trucks, but the company was in the transportation business a half-century before the first primitive motor vehicles were developed. You see, Studebaker was literally in the carriage trade, perhaps the most prestigious brand of horse drawn conveyances in America, and was founded in the 1840s.

Studebaker supplied carriages to at least four U.S. presidents, including the Barouche that Abraham Lincoln rode in to Ford’s Theater on the night of his assassination. Long before the invention of television and radio, the Studebaker company understood how to generate publicity. After Studebaker transitioned to making automobiles in the early 1900s (it was one of the few companies that made both gasoline and electric powered cars in the early automotive era), people got their news and publicity about consumer items from newspapers, magazines, and movie theater newsreels. One way to get the attention of wire services, newspaper chains, and newsreel studios was literally to go big. Making the biggest or tallest of something was sure to get attention.

Studebaker was headquartered in South Bend, Indiana, and in 1926 it built what many consider to be the first dedicated automotive proving grounds in America, about eight miles west of town in New Carlisle. In promotional materials, the 840 acre facility was billed as the “Million Dollar Outdoor Testing Laboratory.” According to an inflation calculator, that works out to about $17.2 million in today’s money, which sounds like a relative bargain. The newest automotive proving grounds in the United States is the American Center for Mobility autonomous and electric vehicle testing facility on the site of the former Willow Run complex in Ypsilanti, Michigan; it was budgeted at $80 million in 2017.

A first-rate facility, the site was ringed with brick pillars topped with limestone plinths and cast replicas of the spoked-wheel Studebaker logo. Studebaker also built a “clubhouse” adjacent to the proving grounds to provide housing for proving ground employees during inclement weather back when an eight-mile drive could be treacherous in the winter.

In 1931, Studebaker managers decided to build a 2.5-to-1 scale replica of their its President Four Season Roadster and put it on display at the proving grounds, billing it as the “biggest car in the world.” It was 41 feet long, 13.5 feet tall, 15 feet wide, and had a wheelbase of 325 inches. Its estimated weight was 11,000 pounds. The steering wheel had a diameter of 44 inches, the headlights were 33.5 inches tall, and the “wire spoke” wheels were 6- foot-8 in diameter and weighed more than a quarter ton each. Electrical conduit was used to fabricate the wire spokes. Firestone supplied the 10-foot tall rubber tires, with proportionately large Firestone logos, of course.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Paul Auman, who was in charge of Studebaker’s experimental body shop, was given the task of building the giant replica in the spring of 1930, so that it would be ready when the actual car was introduced. It took Auman and his team of 60 employees over three months to fabricate the body, mostly out of white pine, after which it was trucked to the proving grounds and assembled.

The massive two-tone green model car was the subject of a nine-minute promotional film shot by prominent director Alf Goulding, who also used the footage in his feature film, Wild Flowers. More people probably saw the promotional short than Goulding’s feature motion picture, as the nationwide RKO theater chain displayed the short about the giant car in its theaters from coast to coast. In addition to attracting attention like the December 1930 issue of Popular Mechanics, whose headline read, “Studebaker Builds World’s Largest Auto,” the big President became a bit of a tourist attraction.

Perhaps it drew too much attention. By the mid-1930s, souvenir hunters, vandals, and the elements had taken their toll on the giant President. It had served its purpose, and the model it was based upon was no longer current. In another big publicity stunt, with firemen from the South Bend Fire Department on hand (just in case), on May 17, 1936, the replica was doused with oil and Paul Hoffman, former president of Studebaker, and Jesse Meyer, the company’s corporate secretary, set a torch to it. Within 30 minutes it was gone. Prior to the conflagration, two of the tires and hubcaps were removed. The two wheel covers are currently on loan to the Studebaker National Museum in South Bend. In the years since Studebaker folded, most of the cast Studebaker logos on the columns surrounding the proving grounds appear to have been scavenged or stolen, though you can still see one at the Studebaker National Museum in South Bend.

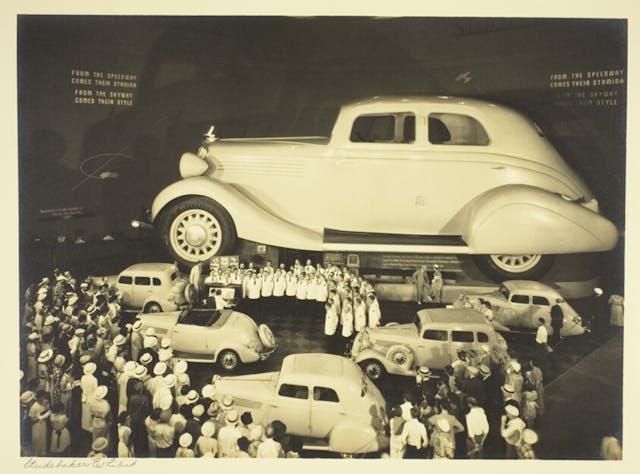

The next big car that Studebaker made, for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, was almost twice as long. Just a few days after the fair launched, the first drive-in movie theater in America opened in New Jersey. You could watch a movie sitting inside your car. At the Studebaker pavilion in Chicago you could also sit in a car to watch a movie, but the car was a giant 1934 Studebaker Land Cruiser, inside of which was constructed a complete motion picture theater with seating for 80 patrons.

To publicize the mammoth motorcar, Studebaker published publicity photos of a large cleaning crew of attractive women standing atop the titanic car, scrubbing it down in shorts and halter tops. The Land Cruiser was 80 feet long and 39 feet tall, with 12 foot wheels. Visitors were given free diecast scale models of the big Studebaker, and you can usually find one or two for sale on the auction sites.

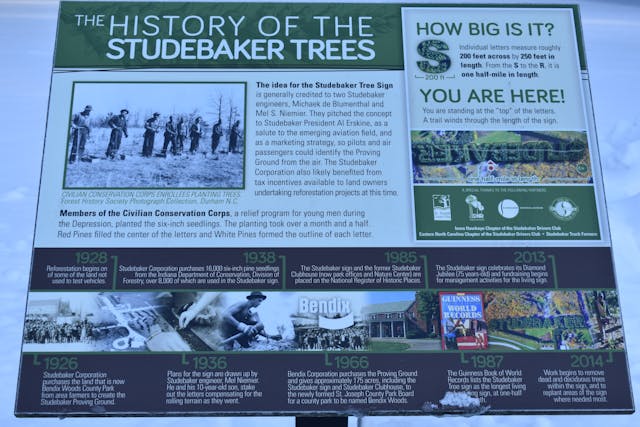

Finally, have you ever heard of the Studebaker Trees? Today you can make a few clicks on a mapping application and see satellite images of the large Studebaker sign that was formed from living trees, but back in the 1930s, few people traveled on airplanes, let alone had access to satellite imagery. (It was two decades before the space race began with Soviet Russia’s launch of the Sputnik satellite.) Most of the period photos were specifically taken by aerial photographers hired by news agencies or Studebaker itself. So what was the point if most people couldn’t see it for themselves? As mentioned above, back then big was, well, a very big thing.

The idea for the tree sign is attributed to two Studebaker engineers, Michael de Blumenthal and Mel S. Niemier, who proposed the idea to Studebaker president Al Erskine as a publicity stunt. Supposedly, it was also a tribute to the growing aviation industry, so that pilots and what few people who traveled by air over northern Indiana could identify the “Million Dollar Outdoor Testing Laboratory” as they passed over it. Another factor may have been the ability of Studebaker Corporation to benefit from tax benefits given for reforestation efforts, and free labor provided by the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Depression-era relief program to employ young men.

In 1936, plans were drawn and engineer Niemier, and his 10-year-old son layed out the sign’s proposed outline with stakes. Two years later, in 1938, Studebaker bought 16,000 six-inch seedlings from the Indiana Department of Conservation, Division of Forestry. About half were used in the planting of the sign and the other half on site land not used for testing vehicles. It took CCC workers almost two months to plant the seedlings, using white pines for the outlines and red pines for the letters’ interiors. Studebaker maintained the living sign until it went out of business in 1966. The Bendix Corporation bought the proving grounds and donated 175 acres of land to St. Joseph County, Indiana, including the Studebaker Trees and the adjacent Studebaker Clubhouse. The donation was to be used to create Bendix Woods County Park. The county built roads and hiking trails through the site as well as picnic areas and shelters. In 1985, the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Subsequently, Bendix sold the proving grounds to Bosch, which in turn sold it to Navistar, which currently operates it as the Navistar Proving Grounds.

Even the most ancient and magnificent of trees, like the giant Sequoia Redwoods of California, have a finite lifespan, and 75 years is a fairly long time for white and red pine trees to live. Trees can be felled by storms—a large storm in 2004 took down a significant number of the original evergreens. Others died from disease and simple old age. Also, over the years, scrub, brush, and deciduous trees starting filling in as undergrowth, diminishing nutrients available for the pines. As the 75th anniversary of the Studebaker Trees approached, fewer than 2000 of the original 8000 trees remained.

In 2011–12, a census of the trees was performed and a management plan was formulated. A challenge grant from a charitable foundation provided funding to begin the removal of dead and deciduous trees as well as invasive species. Sponsors could “buy” a letter for $2000. After funds were raised, vines climbing on the trees were trimmed and treated with herbicides to reduce stress on the pines. Deciduous and diseased trees were removed.

Once all the unwanted vegetation was cleared, the site was prepared for new plantings, beginning with the letter “U” in autumn 2014. Instead of six-inch seedlings, two-to-three-foot saplings of White Pine, Eastern Hemlock, Norway Spruce, and White Spruce were used to fill out the sign. It was decided to go with multiple species to reduce the risk of wide-scale damage by species-specific disease or pests that can wipe out monocultures. Also, the new trees were planted farther apart than those planted by the CCC 85 years ago. Those trees were planted too close together to develop the root systems they should have had.

The Studebaker Trees are in good health these days, and whether or not you’re a Studebaker enthusiast, they’re certainly worth a visit if you’re in the area. Bring some food and enjoy a picnic inside the sign.

Northern Indiana and western Michigan have an abundance of sites of interest to car enthusiasts beside the Studebaker Trees and the Studebaker museum in South Bend. The Gilmore Museum north of Kalamazoo and the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Museum in the original ACD building in Auburn, Indiana, are both within a couple hours drive from South Bend. And if you have time, there’s the RV Museum and Hall of Fame in Elkhart, as well as the National Truck Museum, also in Auburn.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

My dad had a champaign colored 1961 2 ton truck with a 5 speed.

My name is Keri Studebaker and I am part of the original Studebaker’s line of family that had built the cars and started the whole thing! I’m very proud to be as well! This story is a great story! And wonderful history! Thank you again for writing and sharing this knowledge with the world !