Media | Articles

Stan Reynolds, the relic hunter in the sky

Above the waves of wheat, a red-tailed hawk pivots on an updraft. It spots something, turns, and stoops, falling on its prey like a feathered lightning bolt. Beyond, aloft in the cornflower-blue prairie sky, a single piston-engine shifts the pitch of its droning, and a small aircraft banks towards a famer’s field. Like the hawk, its pilot is a restless hunter. And he has spotted something.

That pilot was the late Stan Reynolds, businessman, philanthropist, war hero. He was born to fly, but his roots burrowed deep into the Alberta soil. Born in 1923 in Wetaskiwin, midway between the larger cities of Edmonton and Calgary, he would go on to create one of the largest collections of antique and historic machinery in the country: cars, trucks, aircraft, farm machinery. Yet he hunted not for himself, but to preserve history of his prairie home.

Ted Reynolds, Stan’s father, came north from Oklahoma and set up the family home here in the small settlement of Wetaskiwin. One of the oldest cities in Alberta, it was established on the 16th stop along the railway line headed north from Calgary. Reynolds Sr. ran a garage and was a pilot. He also loved collecting things. He held onto the 1905 curved-dash Oldsmobile that he bought upon arriving in Wetaskiwin in 1910.

Stan followed his father’s lead in appreciation for mechanical things and a love of flying. At 19 years of age, he joined the RCAF and entered basic flight education as a pilot. On a brief leave, a flying accident revealed something of his character.

During WWII, Wetaskiwin was on the route of fighter planes up to Alaska, with some 8000 aircraft overflying the city during the course of the war. On this particular occasion, a Bell P-39 Airacobra had run into engine trouble and crashed nose-first into a snowy field—the pilot was able to parachute to safety. The U.S. Air Force carted away most of the surface debris and left. Young Stan Reynolds went and got his shovel.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

With immense labor, and the help of his father and a tow truck, Reynolds was able to dig up the P-39’s V-12 engine and eventually recover its nose-mounted 37mm cannon as well. He returned the engine and the weaponry to the Air Force, but kept a few rounds of ammunition as a souvenir. He had them tucked away in his garage until the day he died.

As an RCAF pilot, Reynolds was assigned to 410 Tactical Fighter Squadron, operating out of air bases in Scotland. These were night fighters, pitting Bristol Beaufighters and DeHavilland Mosquitoes against the raiding Junkers and Dorniers of the Luftwaffe’s Blitz. His 410 Squadron was among the highest-scoring night fighters in the RCAF. It was dangerous work, though victories far outnumbered losses.

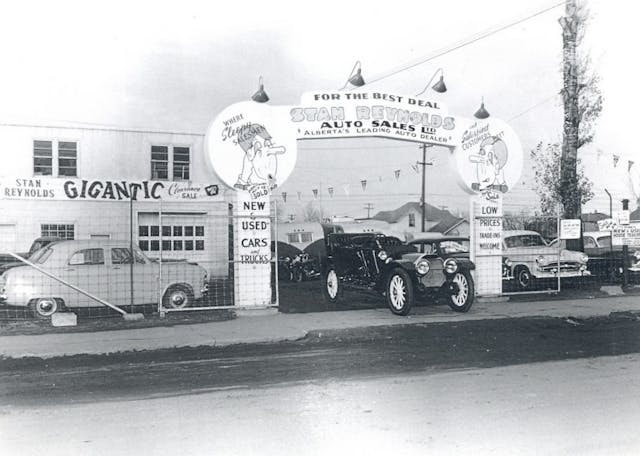

After the war, Stan Reynolds returned to his hometown with $3000 in savings and set up a used car dealership. The work suited him, and the postwar boom brought customers to his door. By the early 1950s, he’d both purchased his own plane, a Cessna 170, and started getting a reputation around town.

“Stan takes anything in trade,” was the reputation, and even his company’s slogan. When a 1911 Overland Model 51 came in on trade on a 1947 Monarch (Overland later became Willys-Overland), Reynolds knew it was too special of a machine to consign to the scrap heap. He restored it, hand-painting the accent lines himself with a badger-bristle paintbrush.

That car still exists, safely tucked away in a museum that bears his name.

The first Reynolds museum was built in 1955 and opened to the public in 1958. The building still exists, located in a field behind the local Toyota dealership.

Along with taking in antique vehicles on trade and rescuing machines from the scrapyard, Reynolds often used his aircraft as a tool for hunting up hidden gems. At the time, Wetaskiwin had no airfield, and he would just land in a nearby field. He even did so at night, using a flashlight pointed out the plane’s cockpit to spot the ground rushing up.

Thus, he was well-used to landing on whatever open ground presented itself. Soaring out over the farms and plains of southern Alberta, he would often spot disused threshers, antique tractors, ancient steam-powered traction engines. He’d circle in, land in a field, then march up to a farmer’s door and strike a deal.

As Reynolds’ businesses expanded into heavy machinery sales, he had the trucking capacity to haul some of the bigger machines back. Often a semi-trailer would go off to deliver a Caterpillar bulldozer and return home with something like a 1911 American-Abell Cock O’ the North Drummond threshing machine. And yes, there’s one of those in the collection.

The Reynolds collection grew. Part magpie, part raptor, the man had an eye for anything collectible and a dedication to preventing Alberta’s history from sloughing off to the scrapyard or to collectors to the south or east. He worked hard to preserve the elements of the prairie home he’d grown up in—steam, steel, wheels, and wings.

The intent was always to preserve and share. By the late 1950s, Reynolds had acquired a staggering number of machines: 2000 cars, 1100 tractors, 500 trucks, 200 steam engines, 300 threshing machines, 800 stationary engines, and 125 aircraft. Among these was a Hawker Hurricane he’d found abandoned; he restored it to flight-worthy condition.

In 1974, seeking to share his interest in history with a wider audience, Reynolds offered the bulk of his collection to the province of Alberta. It took years to convince local government to make a deal, but by 1982, one had been inked. Ten years later, the Reynolds-Alberta museum opened its doors with 1500 vehicles selected from the Reynolds collection.

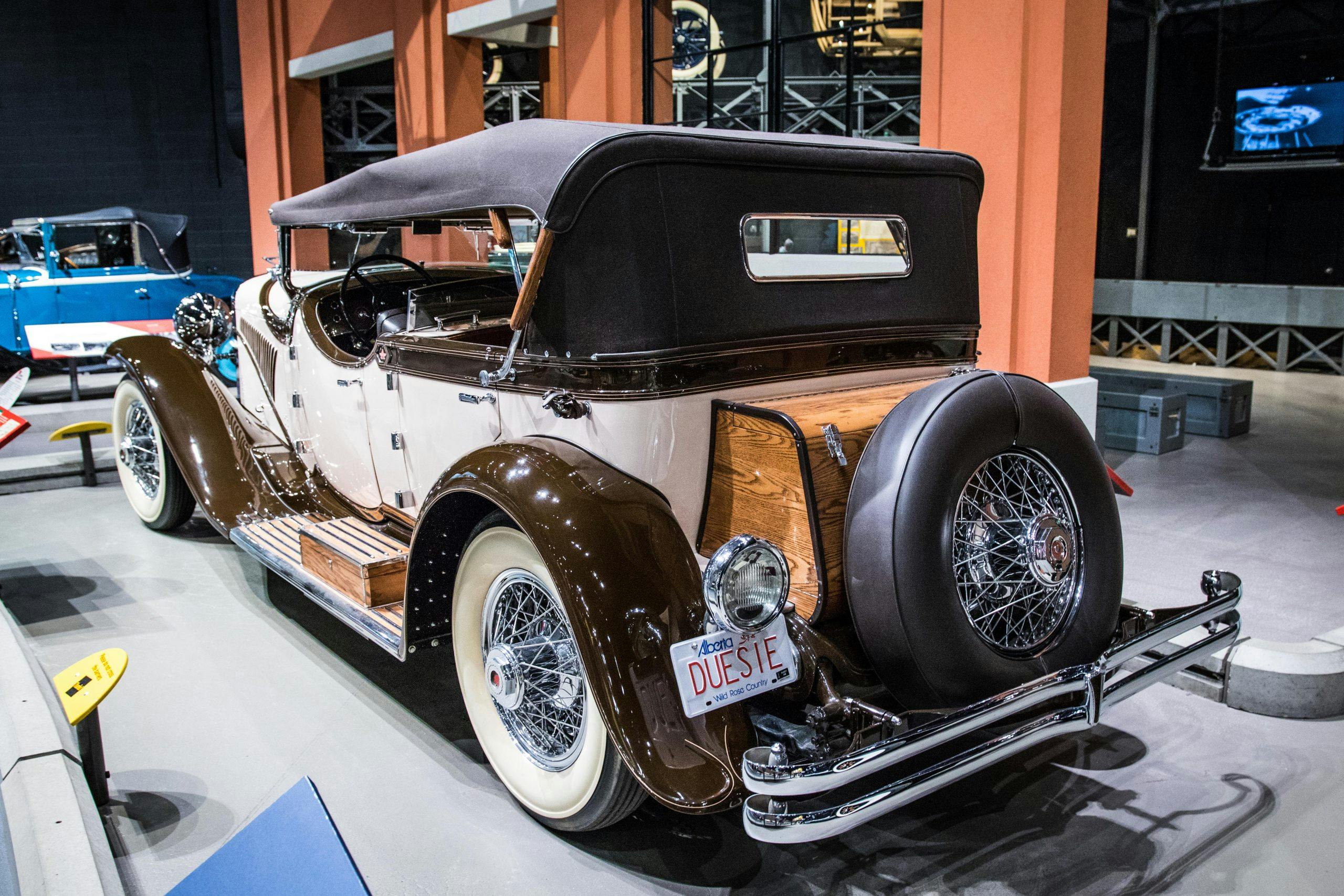

Today, the Reynolds-Alberta museum boasts the second-largest collection of important aircraft in Canada and a staggering array of vintage cars and farm equipment. There are Duesenbergs, McLaughlin-Buicks, looming steam traction engines, and even a delicate little Citroën half-track from the ill-fated Bedaux Expedition. Located just two hours north of Calgary, the collection is well worth the visit.

Stan Reynolds received several awards for giving back to his community and was generally regarded as an epitome of what it meant to be a solid, proud, salt-of-the-earth Albertan. He was appointed a member of the Order of Canada in 1999. He died in 2012, at the age of 88.

If you visit the Reynolds-Alberta museum, you can see his father’s old curved-dash Oldsmobile. You can get up close with that original 1911 Overland and see Stan’s hand-painted stripes still there on the bodywork. You can gaze through a window at the museum’s busy workshop, where mechanics and historians still work hard to restore and preserve relics of the past.

Or you can wander through the outer grounds, among steam-shovels the size of dinosaurs and decommissioned fighter planes. Look to the sky, and you may see a hawk, circling lazily in the breeze. Spare a thought for Stan Reynolds, hunter of history, safeguard of the past.