Media | Articles

Solo Launch: How Britain’s spaceship ’90s sports car failed upon lift-off

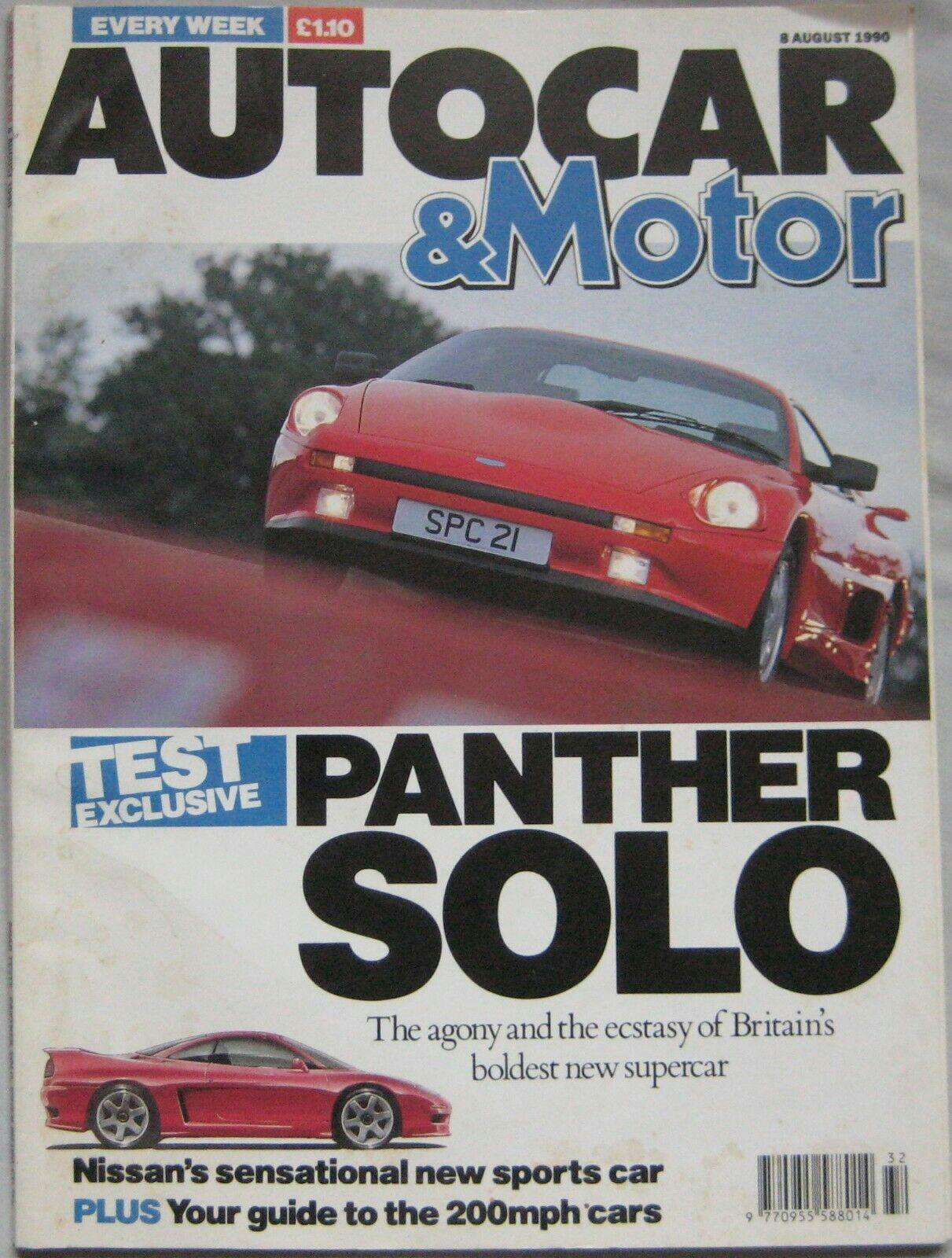

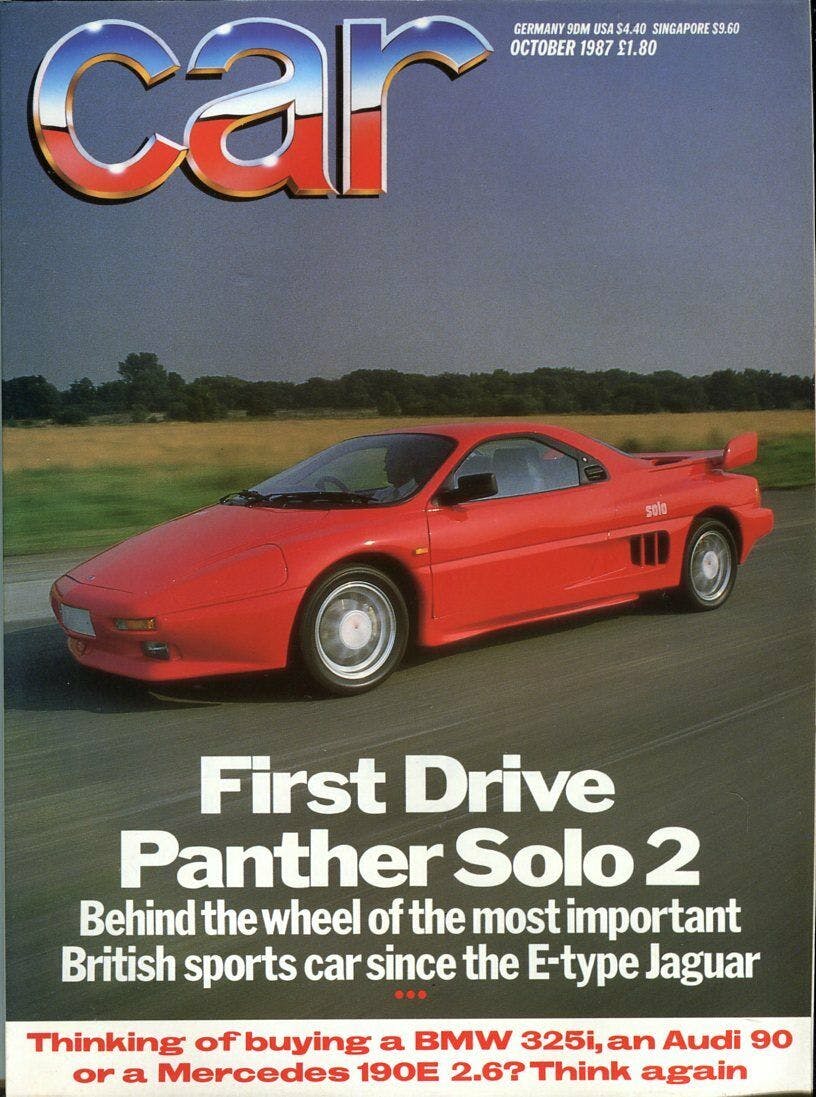

The Panther Solo was “the most important British sports car since the E-type Jaguar,” declared the cover of the October 1987 edition of Car magazine.

The hype for this spaceship-styled, turbocharged, four-wheel-drive coupe was huge. I still remember feeling genuine excitement as a young gearhead, devouring the reviews of the high-tech hope of British automotive engineering.

What made the Solo all the more exceptional is that it arrived almost out of the blue, from a company that previously made the low-volume, and very traditional, Morgan-like Lima and Kallista. These were old-school roadsters, using tried-and-tested off-the-shelf mechanicals from Ford and Vauxhall.

For a company that had made its name with cars styled from the past, the Solo was a massive leap into the future. Originally planned as an inexpensive mid-engine replacement for the Kallista, the first Solo was fitted with a Ford Fiesta XR2 motor and clothed in a weight-saving fiberglass shell. However, with the arrival of Toyota’s MR2, the Solo stood no chance. Panther went back to the drawing board.

Panther’s South Korean owner Young Chull Kim felt that instead of chasing entry-level sports car enthusiasts the company should go after wealthy early adopters with a high performance, high technology car the likes of which the world had never seen.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Solo 2 was penned by Ken Greenley of the London Royal College of Art’s vehicle styling school. It was far, far more ambitious than any British sports car to date. Greenley created a striking cab-forward 2+2 coupe that made a contemporary Jaguar XJ-S look like it was from a bygone era. With side intakes that wouldn’t appear again until the Ferrari F355, ingenious, rotating, hidden headlamps, and the kind of flamboyant rear wing not seen outside of a race track, it was one of the most visually exciting British cars ever designed.

It wasn’t just a styling revolution it was a showcase for exotic new materials, construction and engineering. The monocoque used a steel spaceframe with an aluminum honeycomb, sandwiched between sheets of epoxy resin impregnated fiberglass. Greenley’s bodywork was in a Kevlar/Carbon composite and was then bonded to the lower chassis using a special aerospace-spec adhesive. Panther partnered with racing legends March to perfect this unique construction, which saw early use of carbon fiber at high stress points, and the race team also honed the car’s aerodynamics.

Suspended on Ford-sourced MacPherson struts at the front and double wishbones at the rear, the Solo also used Ford power. Sitting amidships was the two-liter turbocharged four-cylinder, 200 hp engine from the Sierra RS Cosworth. A Borg Warner T5 transmission and Panther’s own transfer box sent power to all four wheels. The Solo would nudge 150 mph and accelerate to 60 mph in under seven seconds.

When Panther unveiled the car at the 1987 Frankfurt Motor Show it was met with rapturous applause and gushing praise in the motoring press. “Panther, one of the smallest manufacturers in the world has produced a car with more flair, innovation and design integrity than massive motor corporations ever show,” said Autocar magazine.

The order books began to fill up, and Panther spoke of building 600 Solos per year. But the truth was the car was nowhere near production-ready. Working with the exciting new composite materials was a steep learning curve, leading to warped panels and issues with the paint, delaying deliveries by years.

Meanwhile, owner Kim was facing pressure from his family over how much he was spending on the sports car business. He ultimately sold 80 percent of Panther to Dong-A-Motor, which was a part of Ssangyong. Costs were cut, the firm was moved to a new factory, and staff began to leave.

Eventually, in 1989 the Solo received its Type Approval and deliveries could begin. By this time, however, the price had risen dramatically from the £28,000 announced at launch to almost £40,000 (equivalent to almost $140,000 in today’s money). Of the 125 people who had put down a deposit, just 13 stuck with the Solo and received their cars before production was canceled in early 1991.

From such high hopes came bitter disappointment—for the engineers and designers, the early adopters, and the young enthusiasts like myself who never got to see one outside of the pages of a magazine.