Media | Articles

Remember the Rochdale Olympic? Neither Does Anyone Else, Sadly

When Harry Smith and Frank Butterworth set up Rochdale Motor Panels and Engineering in 1947, they probably had no intention of becoming a carmaker. Their new company was formed to repair cars, but within a year they had embraced the idea of building their own aluminum bodyshells for Austin Seven owners who wanted to go racing in 750 Formula competition.

Sold under the Rochdale brand, the company’s Austin-based specials proved a hit, with around 50 selling for £300 (about $800) apiece. As the 1950s dawned, many companies started to dabble with fiberglass. Rochdale was one of them, and by mid-1952 its first plastic car was on sale. Called the Mark Six and essentially a kit of parts for the home builder to put together, Rochdale had another hit on its hands.

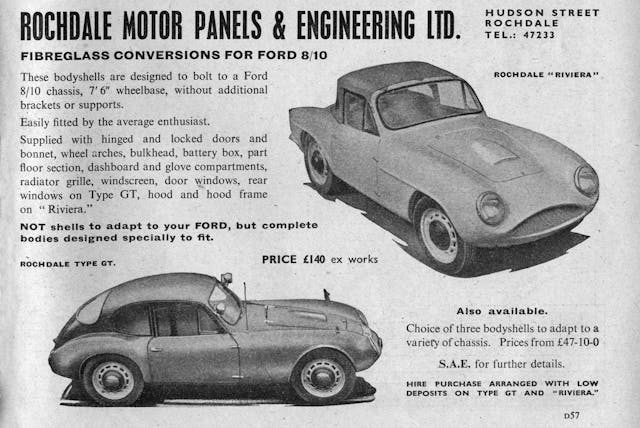

Over the next five years, Rochdale introduced a series of fiberglass roadsters that were produced to an ever-higher standard, culminating in the GT of 1957; the company’s first fixed-head model. More comprehensively engineered than anything that had come before, and of a much higher quality, the GT was based on a Ford Popular chassis. By 1959, a drop-top GT was introduced, called the Riviera, and once again business boomed with waiting lists growing, despite extra production staff being recruited in a desperate bid to keep up with demand.

Just as the Riviera was unveiled, Rochdale started to develop something altogether more high-tech: a sporting saloon with a fiberglass monocoque, powered by a Morris Minor A-series engine. All of Rochdale’s previous cars featured a separate steel chassis, but this new one would be lighter and more rigid than anything it had produced before. It would be called the Olympic, because it was announced just as the Summer Games were opening in Rome.

Lotus was the first carmaker to introduce a fiberglass monocoque with its Elite; Rochdale was the second. The key figure behind the Olympic’s development was Richard Parker, who had played a part in the Lotus’ gestation; by a coincidence he just happened to own a Rochdale already.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Olympic’s monocoque featured steel reinforcement for the windscreen pillars along with the engine and suspension mounting points. Very cleverly, the whole bodyshell was molded in one piece without any joints or seams, and while it was still in the mold the bulkheads and wheel arches were bonded in, to create an immensely strong and aerodynamic monocoque.

When it went on sale late in 1960, there was a choice of A-type (Morris Minor or Riley 1.5 running gear), or F-type (Ford 1172-cc side-valve). Priced at $440 and $700, respectively, in kit form, the Ford setup proved incredibly unpopular, which is why it was soon dropped. Rochdale also offered ready-built cars with Riley 1.5 running gear at $1880, or Morris Minor/Ford Anglia 105E mechanicals for $1675.

The rear suspension was by coil springs and telescopic dampers, with radius arms and a Panhard rod locating the rear axle, while up front there were torsion bars. Standard equipment included wind-up windows and opening rear quarter windows, and buyers could opt for green, blue, red, or ivory fiberglass, with other colors available for special order.

In a bid to recoup as much of the near-$30,000 development costs as quickly as possible, Rochdale made bodyshells available on their own at first, but the company quickly moved to a model whereby kits were sold instead, and these included all interior trim, wiring, and all mechanical parts. Just 50 hours were needed to get the car roadworthy. Predictably, long queues started to form.

And then disaster struck, as Rochdale’s factory was completely destroyed by a fire in 1961, resulting in the loss of all molds and eight Olympic bodyshells. Customers were told they’d have to wait an indefinite period for Rochdale to find new premises and get up and running again. Many canceled their orders, and suddenly things were looking bleak.

However, The Motor published a road test of the Olympic soon after the fire, and thanks to the magazine’s obvious enthusiasm for this fascinating car, once again the queues started to build. The review gushed: “The completed Rochdale Olympic as we have been driving it offers quiet, comfortable, controllable and altogether effortless performance which seems unrelated to such a low cost.” The car’s strength, aerodynamics, ride, handling, and low weight were also praised.

With just 60 hp on tap, the Olympic was capable of 0–60 mph in 11.9 seconds, with a standing quarter-mile time of 18.5 seconds and a top speed of 102 mph, which was limited by the gearing. With the ability to also average 40.5 mpg, there was a lot to like about the Olympic, which The Motor also claimed was “a remarkably refined and well-designed car” with an exceptional standard of finish.

Rochdale quickly found new premises, and it wasn’t long before it was back in business, although the loss of its complete stock of molds meant its only product now was the Olympic. To increase interest in this, Rochdale introduced an even lighter bodyshell for competition use, along with other powertrains, including the MGA 1600 and Coventry-Climax. With a typical curb weight of just 1325 pounds or so, performance was sprightly no matter which engine was fitted.

In 1962, major reductions in purchase tax cut the cost of new cars, which made kits a lot less attractive. Many kit car producers went to the wall, but Rochdale soldiered on and introduced the Olympic Phase II at the January 1963 London Racing Car Show. A change to Triumph Spitfire–derived double-wishbone front suspension, rack-and-pinion steering, and 9-inch disc brakes improved things further, while the availability of a 75-hp Ford Classic engine was another welcome step. With some tuning, 100 hp could be coaxed from this 1.5-liter four-pot, to provide seriously sparkling performance.

Other improvements ushered in by the Phase II included two 5-gallon fuel tanks in place of the single 6.5-gallon item previously fitted, the adoption of an electric fan for better engine cooling, standard windscreen washers, and higher-quality interior trim. At $2050, the price of a kit was still very reasonable (especially as the build time had been cut to just 35 hours), and so was the $2600 cost of a fully built car, especially as the Elite’s prices were $3600 and $5300, and it was only a little bit quicker on the road.

By the end of 1963, a 78-hp Ford Cortina GT engine was available. This 1498-cc unit could push the Olympic all the way to 114 mph, which was beyond the capabilities of a Triumph Vitesse, MGB, or Sunbeam Alpine, and unsurprisingly the motoring press of the time lapped it up. Motor Sport claimed that it was “one of the most desirable two-seaters we have come across.”

By this point, however, despite the accolades Rochdale was losing interest in car production, and it had moved into heating engineering, which only accelerated the rate at which Olympic production was reduced. By 1965, things were made worse by difficulties obtaining some key components, and it was this that led Rochdale to offer the Olympic only as a bodyshell. Just 10 were sold in 1967 and the same in 1968, and by 1972 the Olympic was finally put out to grass, with around 250 Phase Is and 150 Phase IIs built. For a car that was so desirable for its design, construction, aerodynamics, value, and performance, the Olympic deserves a far higher profile than it has.

There is a flourishing Rochdale Owners Club of which I am Chairman and would invite anyone interested in the marque to join us. Application is via the ROC website or you can mail me directly for more information at j-h-evans@tiscali.co.uk.

It’s amazing how in the world of what seems like daily new hypercar entries, stories of ghosts from the past like the Rochdale remain so fascinating. Look forward to more.

I read the Motor’s road test in their annual compendium of tests and was very impressed — enough so that I went to visit them when I was working at Shell’s Research Centre near Chester one summer. Very much a cottage industry, so I was not surprised about the low production figures. How is the structural rigidity of the fiberglass monocoques after sixty years?

The VW headlights give it a very appealing face despite the protruding ‘beak’ of the air intake. The GT is the best-looking, I would say, but the Olympic is the technological star turn of the marque. Given how utterly bad, if not absent, British heating systems were well into the 1970s (and I remember them very well!), it is not surprising that the obviously very competent Rochdale company shifted their focus to a mass-market field in which there was endless unsatisfied demand. I daresay they made a lot more money than they ever did building tiny sporting cars! Thank you for this charming look at the heyday of kit cars in Britain. I don’t remember ever having seen one.

Although a lifetime resident of USA, I have been aware of the Rochdale for a long time – they come up for sale from time-to-time on eBay UK and I’ve been tempted!

I never heard of Rochdale. It’s a cool looking small car.

Never heard of them. I like it!