Media | Articles

Mr. Mohs and his amazing motor cars

Mohs Motor Car, the brainchild of serial entrepreneur Bruce Baldwin Mohs, built just four cars, selling but two of them. Despite that limited output, Mohs made his mark on automotive history. Unfortunately for Mr. Mohs’ legacy, almost all of the acclaim for his creations include words like “oddest,” “weirdest,” “strangest,” “unusual,” “ridiculous,” and the perennially clichéd “worst.” Of course, the three Mohs Safarikars and singular Mohs Ostentatienne Opera Sedan were just as eccentric as their creator. Perhaps this was to be expected, coming from a man whose autobiography is titled The Amazing Mr. Mohs, and whose table of contents lists “37 Eccentric Chapters.”

I won’t say that Mohs had delusions of grandeur. It seems more of a humorous affectation, but he liked to start businesses and give them impressive names, hence Mohs Motor Car. While serving as a pilot in the Air Force, Mohs bought a six-passenger Cessna 185 floatplane, started selling excursions, charter flights, and air taxi services in Wisconsin, and called the enterprise the Mohs Seaplane Corporation. That augmented income from the hotel and restaurant that he inherited from his parents, a business whose success allowed Mohs to pursue his inventive dreams. Mohs’ other business ventures included selling chemicals for the electronics industry and making technical props for Hollywood filmmakers.

Colin Chapman, who founded Lotus, was also the offspring a hotelier. Unlike Lotuses, however, Mohs’ vehicles were serious heavyweights; he based his creations on International Harvester trucks. While Mohs’ two vehicles share little in the way of styling, except for prominent Rolls-Royce inspired radiator grilles, they’re both charmingly weird and both deserving of the word “massive.”

Mohs’ interest in cars started early. It seems as though he was willing to put a motor on just about anything, even scavenging the engine from his father’s cement mixer to power one of his inventions. Perhaps to keep his own equipment intact, the senior Mohs bought Bruce a Falls 8 race car, originally built to race at Indy, for his 12th birthday.

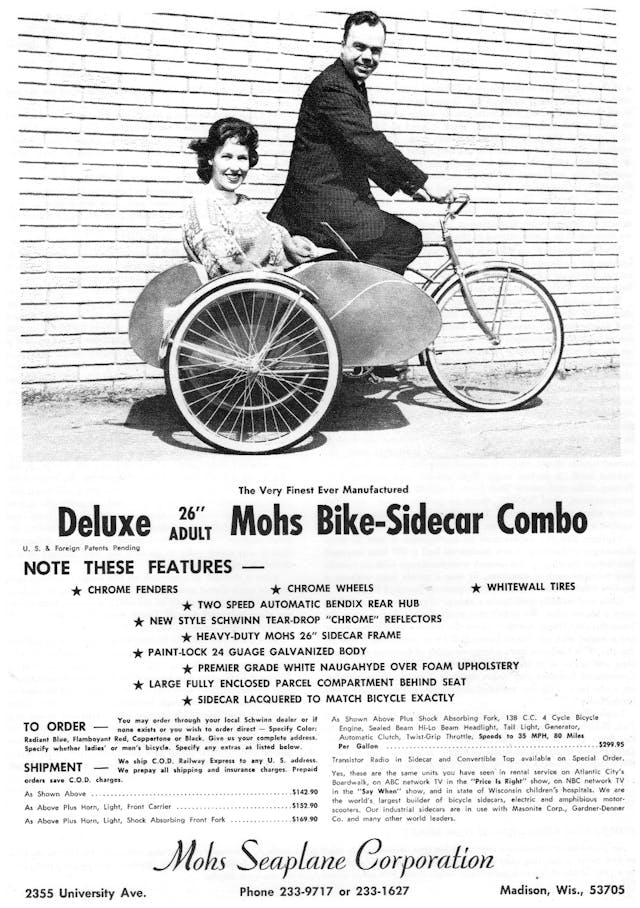

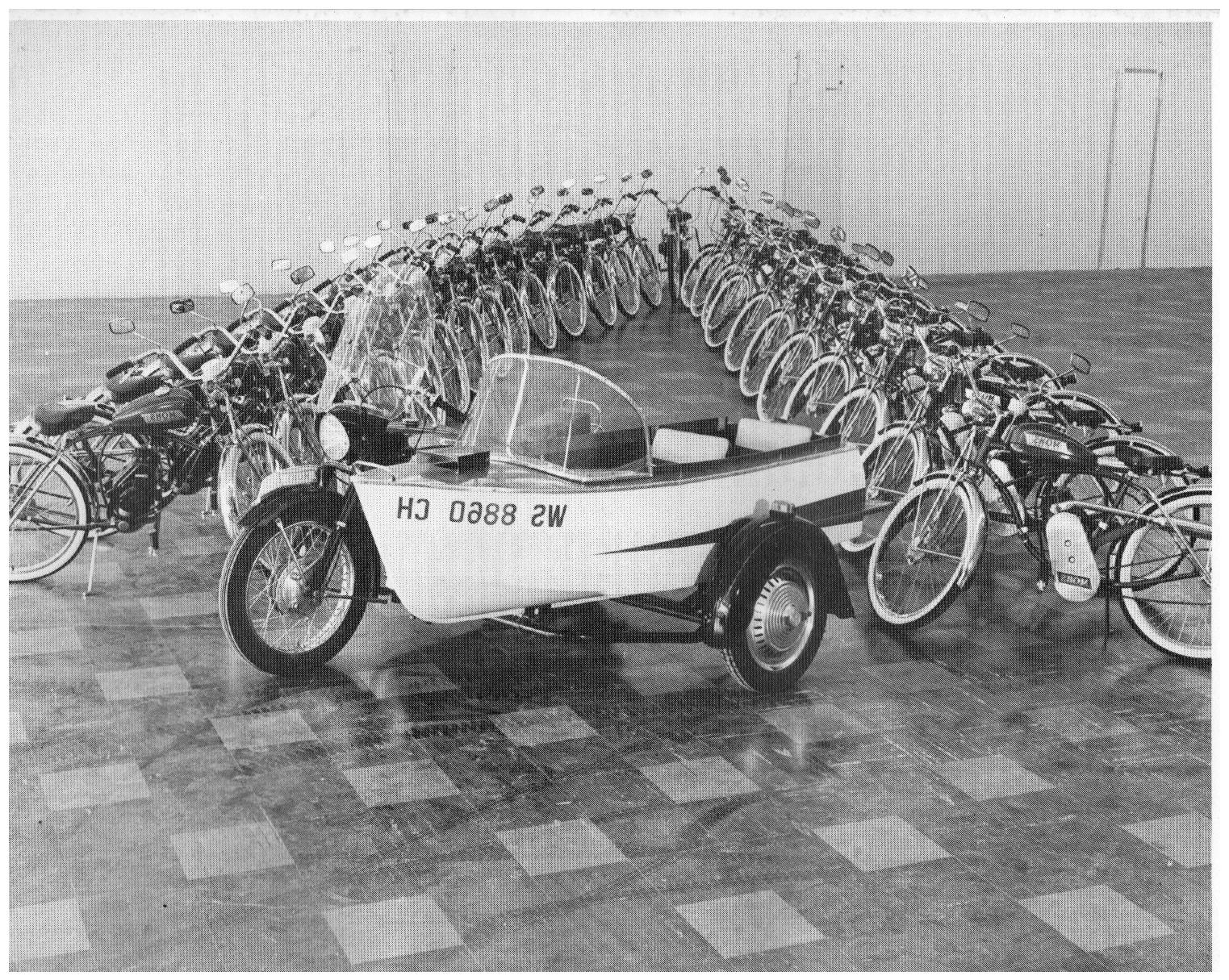

Considering his interest in all things motorized, it’s a bit surprising that Mohs’ first successful transportation-related enterprise had no motor: it was a sidecar for bicycles, introduced in the early 1960s. What started as a Christmas gift to go with the Schwinn bicycle that his niece received, ended up becoming a modest hit. Mohs’ niece and her friends liked it so much that he made a second one, drove down to Chicago and convinced a toy buyer at Marshall Fields’ flagship department store to put it on display.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Despite the fact that the $60 sidecar was double the cost of the Schwinn to which it was attached, it sold immediately. Mohs ended up manufacturing a thousand of them, eventually reaching the point where he licensed another company to make and sell them. In addition to those sold to the bicycle market, Mohs made industrial versions with bins instead of seats, for carrying parts around factories, and a one-off “hearse” for a funeral home. A lifelong boating enthusiast as well, Mohs also made a motorcycle sidecar that carried a detachable dinghy.

Based in Wisconsin, where Schwinn was also located, Mohs developed a relationship with the bicycle company. In the mid-1960s he patented a motor-driven bicycle and put it into production as the Mohs 85cc Ultralite Motorcycle, essentially a pedal-less Schwinn with a small engine mounted to the crank housing, and he again ended up licensing out production. Mohs’ autobiography says that they initially sold well, but they could not compete when the Honda 50 (aka Supercub) entered the U.S. market.

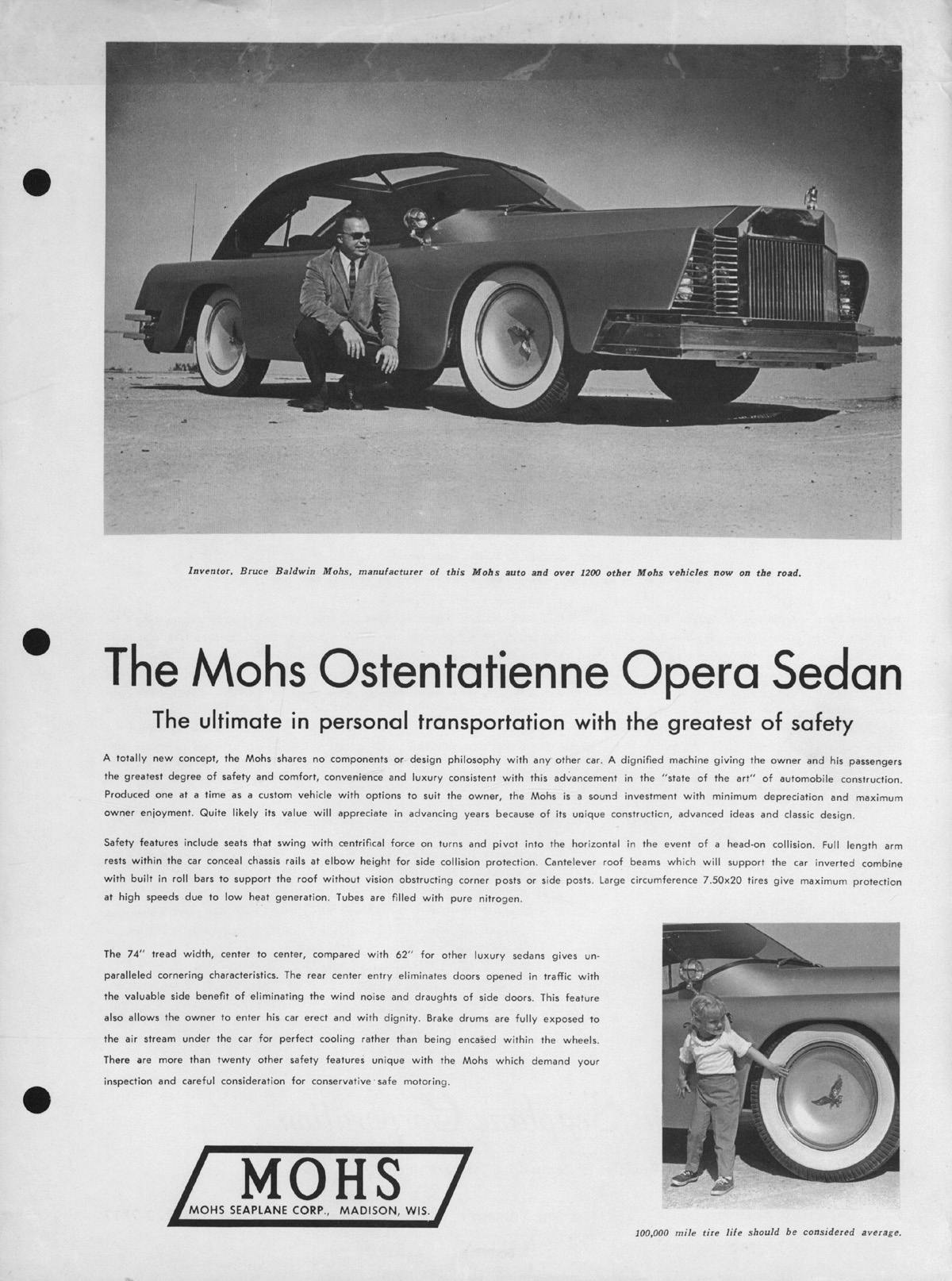

Having made and sold “sidecars” and “motorcycles,” Mohs turned his attention to bigger things. His first attempt at building a full-size car came in 1967 with the Ostentatienne Opera Sedan (OOS), marketed as “The ultimate in personal transportation with the greatest of safety,” seizing on two automotive trends at the time. That era was rife with American automakers introducing “personal luxury” cars, essentially full-size coupes with styling flair, like the Pontiac Grand Prix or Lincoln’s Continental Mark series. Automotive safety was also a hot-button issue, spurred on by Ralph Nader’s book Unsafe At Any Speed.

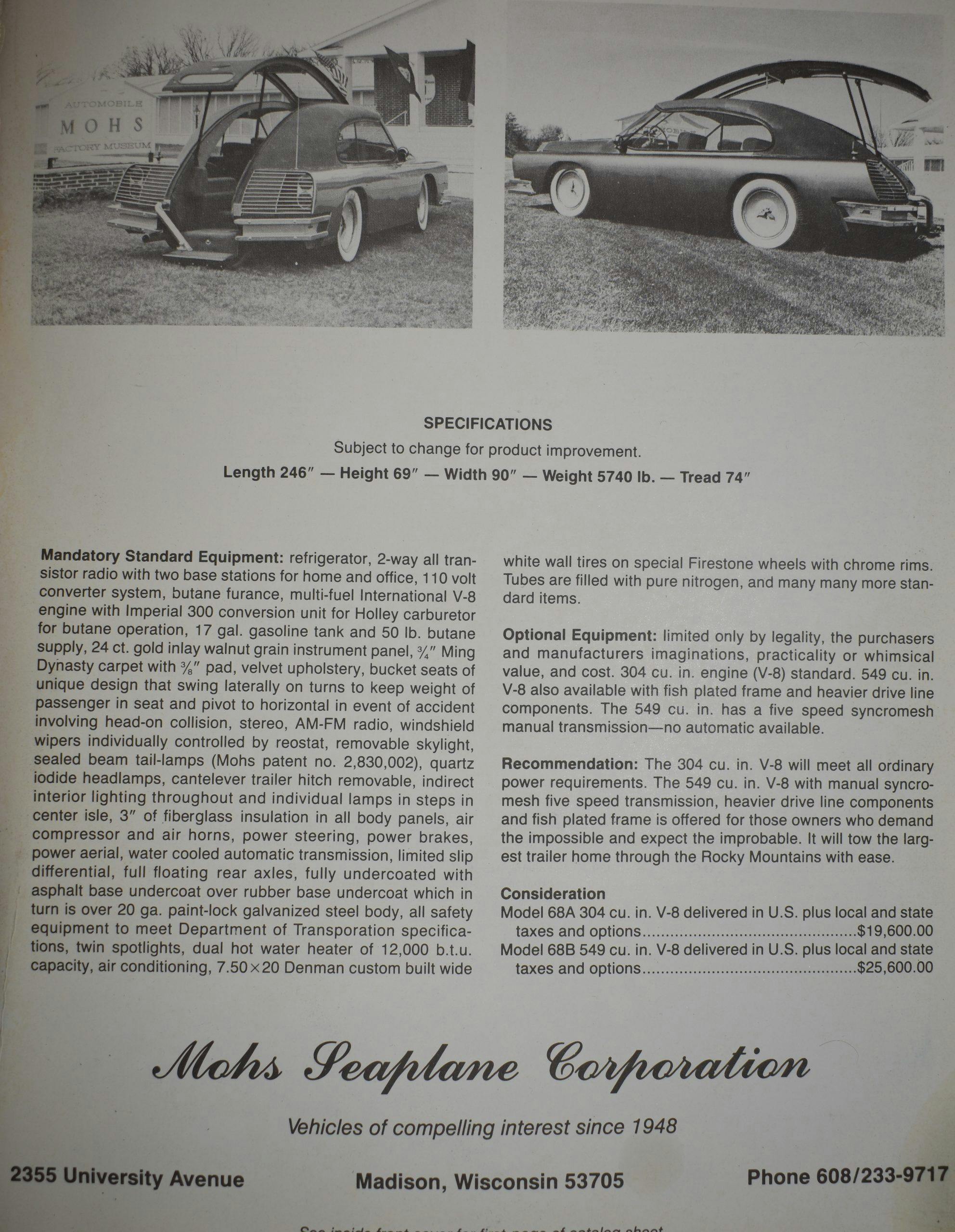

Based on an International truck chassis with a 119-inch wheelbase and powered by that firm’s 304-cubic-inch V-8, the OOS was said to be safer than a conventional automobile because it eschewed side doors in favor of a single, cantilevered door that opened vertically, hinged at the windshield with the opening at the rear of the car. The roof was also cantilevered from the rear, with only the barest suggestion of A-pillars. The roof structure was reinforced with steel beams said to be able to support the weight of the car in the event of a rollover. (How safe you’d be in a rollover, trapped inside the vehicle, was an open question.)

Mohs’ promotional literature touted the ability to enter the car “erect and with dignity.” That form of egress was necessitated by the solid steel beams in the Opera Sedan’s sides, included to protect passengers from side collisions. Those two sets of steel beams determined much of the car’s shape, though the final form ended up looking something like the offspring of the Chrysler Norseman concept vehicle and a Checker taxi, with a splash of 1970s-era “pimpmobile.”

The Opera Sedan was finished in a rich gold paint, while the unconventional roof was covered in black vinyl. The bright red interior was trimmed in the plush pile carpeting that was popular in the 1960s. Befitting a car of its size, the bumpers are also massive. All of that steel adds up, and with a driver and passenger the Ostentatienne Opera Sedan tips the scales at over three tons. Perhaps the strangest safety feature are the seats that swing in response to centrifugal force and are said to pivot to a horizontal position in the event of a head-on collision. Since only the prototype Opera Sedan was ever made, none of those safety features have ever been tested for actual effectiveness.

Mohs retained the International Harvester truck’s 20-inch wheels and mounted them with huge whitewall tires that he filled with pure nitrogen, years before it became a fad. Solid-disc hubcaps filled the rims. Mohs said the OOS could be fitted to customer requests, much like a coachbuilt Bentley or Rolls-Royce, even offering oriental rugs. Options included a butane-powered RV furnace, a refrigerator, and a CB radio.

For all of the supposedly modern safety features on the OOS, the car retained tubed tires as well as the stock International drum brakes at all four wheels. The International’s 74-inch track width, roughly a foot wider than most full-sized luxury sedans, was promoted as a benefit that provided “unparalleled cornering characteristics.” Considering the vehicle’s total weight, including the mass of the door and roof beams that made the vehicle top-heavy, plus its unrefined truck suspension, Mohs was probably correct that the Ostentatienne drove nothing like a Lincoln or Cadillac. Just not in the way he hoped.

To reassure potential customers that Mohs Motor Car was a well-established player in the automotive field, promotional literature for the OOS touted the fact that the company had manufactured “over 1200 other Mohs vehicles now on the road.” Perhaps “on the sidewalk” might have been more accurate; the vast majority of those 1200 “vehicles” were Mohs’ bicycle sidecars.

Mohs priced the base Ostentatienne Opera Sedan at $19,600 in 1967, with a fully loaded vehicle costing $25,600. The latter price is about $200,000 in 2021, which helps to explain why Mohs only built the single prototype.

Eventually, the OOS ended up in storage, where it sat until 2009, when retired school teacher Fred Beyer, a friend of Mohs, coordinated its restoration by students attending automotive tech programs at two Wisconsin high schools: Freedom High School and Shawano High School, the latter of which is also known as “Hot Rod High.” Four months and more than 400 hours of labor went into restoring the body and gold paint, including repairing rust and even fabricating necessary panels. The completed OOS has been featured in Hot Rod magazine, as well as Kustoms and Hot Rods. It is currently on display at Wayne Lensing’s Historic Auto Attractions museum in rural Roscoe, Illinois.

Lensing also owns an example of Mohs’ second car, the 1973 Safarikar. While Mohs never sold an Opera Sedan, the Safarikar did get off the ground with three vehicles manufactured. Two of these cars were sold, and two total have survived.

The Safarikar, as you might guess from the name, was designed as a capable off-road vehicle with all of the comforts of an ultra-luxury machine. Again, Mohs chose International mechanicals, this time the chassis, suspension, and 392-cu-in V-8 drivetrain from the Travelall SUV. Aluminum-tungsten alloy bulkheads with steel outriggers support aluminum body panels. Those panels are not painted but rather covered with foam padding and upholstered with 40 yards of Naugahyde, because of course they are. Strange as it sounds, Mohs was harking back to early days of the automobile, when most roofs and even some body panels were covered in padded leather or vinyl.

He characterized the folding, multi-piece hardtop as a dual-cowl phaeton, but don’t expect it to look like a Packard or Duesenberg with that body style. As always, Mohs went his own way. Everything seems oversized on the Safarikar, from the bumpers to the Rolls-Royce-ish grille, which is somehow even larger than that of the Opera Sedan. With such a classic radiator grille up front, of course the Safarikar has a continental tire kit out back. Seating up front features three bucket seats, the same model seats as were used by Steve McQueen’s Baja Boot off-road racer. There’s plenty of legroom in back, in case passengers want to stand and shoot while on a hunt, and if the trek stretches overnight, the rear bench seat doubles as a bed. Options included a television and four-wheel drive.

Mr. Mohs’ idea of an upscale hunting vehicle was in reality a kind of wacky American take on the British shooting brake, and the video below illustrates the absurdity of how some of Mr. Mohs’ innovations were “engineered.” The idea that the Safarikar—with its gold-plated giant eagle hood ornament—could be marketed to elite buyers was, to put it generously, wishful thinking. The windows don’t roll down but rather use a sliding configuration like old British sports cars might have had. To open the doors from the outside, there are no exterior handles nor some kind of remote control device. You slide open a window, reach in and pull up on a lever connected to sturdy steel latches that operate the door mechanism. The two-part folding roof is entirely manual and the landau-bar-looking struts that support the front section look rather spindly when retracting the roof. To open the hood you need to poke a separate 18-inch long hook through the grille to reach what is likely the original International Harvester hood release. “Panel fitment” isn’t a phrase one utters within sight of a Safarikar.

Mohs had a thing about strange doors. The Opera sedan had just one and it was located in its roof. The Safarikar’s two doors were in conventional locations, but ostensibly were intended for passengers to be able to shoot at prey while the vehicle was in motion. The powered doors are mounted on sliding rails and open horizontally, to the side of the vehicle. While they make it possible to shoot from the car, they aren’t as effective in facilitating ingress or egress.

Of the three Safarikars that Mohs built, it was once thought that only Lensing’s car survived. In 2007, however, a second Safarikar was sighted and referenced in a 2007 Antique Automobile of America (AACA) forum. Two years later, an enthusiast named Mark Zalutko had located the owner, saw the car rotting in a parking lot in Georgia, bought it, and started a four-year, $650,000 restoration. Since then, the Safarikar has been featured at the Amelia Island and St. Johns concours events and has won awards at the AACA’s Hershey meet. Zalutko has enjoyed it for a decade, but earlier this year his Safarikar was listed for sale by Hyman Ltd., with a fixed price of $349,500. Most recently, Hyman offered the Safarikar for auction on Bring A Trailer, where it failed to meet reserve with a high bid of $90,000.

Bruce Mohs died in 2015 at the age of 82, eccentric until the end. It’s nice to know that he lived long enough to see his cars respectfully displayed at museums and at the automotive world’s most prestigious events. People mocked his cars, but you can be sure that Bruce Mohs was equally amused that these weird wonders of his imagination came to life at all. In the end, he maybe even got the last laugh.

This was quite Interesting. I worked for Graber Mfg. in Middleton about 1967. I have a Sales Brochure & have no idea how I got it. Have wondered about the Car & it’s inventor for many years.