Media | Articles

Looking back at 60 years of the Renault 4, the do-it-all “blue jeans” car

In 1871, when a Latvian-born American tailor named Jacob W. Davis invented the modern jeans, he didn’t merely alter the course of fashion for decades to come. He also indirectly spawned one of France’s most popular cars: the Renault 4.

Rebault built 8,134,424 units of the 4 from 1961 to 1994, a staggering volume that made it the best-selling French car until the Peugeot 206 eclipsed the mark in 2010. Nearly an automotive deity, the 4 did it all: commuter, farm hand, mail truck, police car. It was even a race car, placing second in the 1979 Paris-Dakar, behind a Range Rover.

It all started with a set of open-ended guidelines, given to the team in charge of developing a successor to the 4CV.

“Make it less ugly than the 2CV”

Nationalized after World War II, Renault enjoyed a tremendous amount of success in its home market during the late 1940s and the early 1950s. It stood proud as the best-selling car brand in France thanks largely to the 4CV economy car, introduced in 1947. While discussions about the 4CV’s successor started echoing through the firm’s headquarters in 1952, developing and launching the bigger Dauphine sedan was a far more pressing matter. Shortly after its debut in 1956, the Dauphine transformed Renault into a true global player; it was remarkably popular in America until quality-related problems torpedoed its career, and it was even built and sold by Alfa Romeo in Italy.

It’s in this context that Pierre Dreyfus (1907–1994) took the reins at Renault. He was appointed CEO in 1955 after his predecessor, Pierre Lefaucheux, rolled his Frégate in icy weather and was killed when his briefcase in the rear seat became a deadly projectile. Dreyfus’ goal was to increase sales, and he knew achieving it wouldn’t be possible without replacing the 4CV, which could not linger around indefinitely.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Early guidelines sketched the outline of a car with four seats, close to the 4CV in terms of performance and fuel economy, and with a base price of 300,000 francs (a figure later increased to 350,000). Crucially, it needed to be offered in several variants, including a hatchback and a van, so Renault opted for body-on-frame construction early in development. Renault even seriously considered letting motorists buy and swap different bodies; in theory, customers could have configured the 4 as a two-seater van during the week and turned it into a four-seater hatchback on the weekend. Nothing was off the table.

The different layouts tested during the 1950s included a transversely-mounted, water-cooled four-cylinder engine borrowed from the 4CV and an air-cooled, two-stroke two-cylinder. Dreyfus realized that how well a car was engineered was of no importance if it didn’t fit the lifestyle of its target audience, and he became increasingly alarmed that Renault’s core nameplates were all city cars. Models like the 4CV and the Dauphine weren’t viable on dirt roads, where the Citroën 2CV reigned supreme; they were too low, yet buyers were beginning to look for a daily driver they could take hunting, or to a family picnic, on the weekends. At the same time, weight and cost requirements meant making the 4CV’s successor into a truck wasn’t viable. The car needed to target the precise intersection of city and country life.

“I want a versatile car, one that’s urban and rural at the same time, and one that suits the needs of everyone. Call it the blue-jeans car,” Dreyfus wrote in 1956. He weighed in on its design, too. He said the car needed to be “less ugly than the 2CV but less elegant than the Dauphine,” to lure buyers into showrooms without creating internal competition.

Although somewhat vague, these simple directives shaped the 4. One of the best-selling French cars was soon to be born.

Globe-trotting prototypes

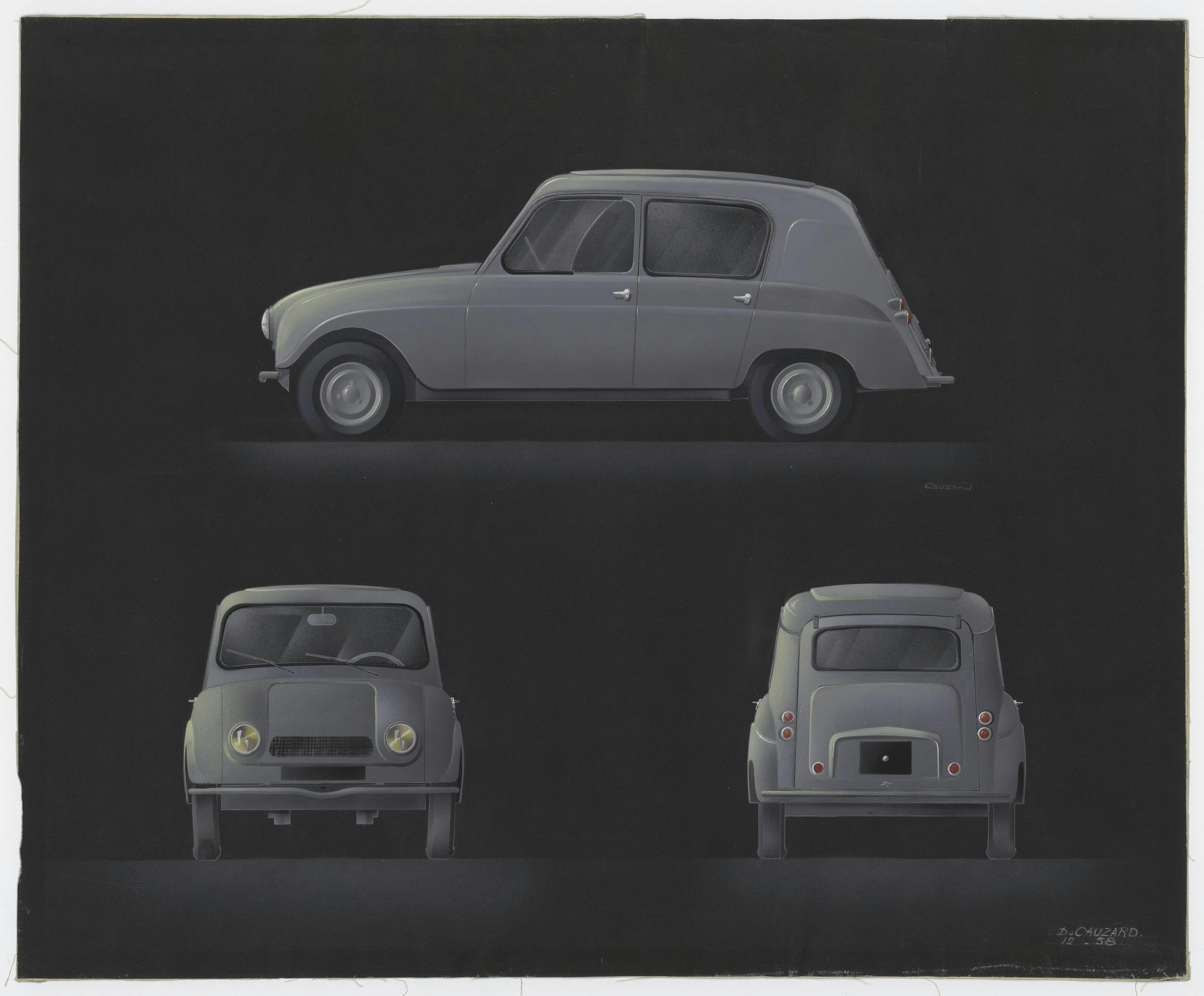

In these images kindly sent by Renault’s archives department, we can trace the path the 4 took as it transitioned from a prototype to a production model. Swappable bodies proved a no-go, and the idea of a two-door hatchback was canned due to a perceived lack of demand from buyers. Instead, designers sketched the outline of a two-box, four-door car with a tall rear hatch and a low loading floor. Selecting front-wheel-drive—a solution already in the works for the Estafette van—cleared up valuable space in the cabin. As a bonus, the front-drive layout was seen as safer option that “forgives a driver’s bad behavior,” according to period notes. (Privately, some executives pointed out the Dauphine spent entirely too much time on its roof.)

Road-testers put precisely 2,901,253 kilometers (about 1.8 million miles) on the 4 during the development phase. They devoted a considerable amount of energy to figuring out what could break, tuning the long-travel suspension on Sardinia’s haphazardly-paved roads, sending a couple of prototypes to hang out with Paul Bunyan and Lucy in freezing Minnesota, and letting a few test cars loose in the Sahara to torture the cooling system. Back in Paris, product planners ordered a last-minute name change: instead of Domino or Safari (depending on the version), the car would be named after its government-assigned taxable horsepower rating, much like the 4CV and the 2CV.

3 versus 4

Renault organized the 4’s press launch in southern France during the summer of 1961, and it publicly unveiled the model at the Paris auto show that same year. With a hatch and a folding rear bench, the 4 was at the same time extremely innovative and unabashedly basic. Its front windows, for example, slid forward instead of winding down.

At launch, the range included two basic models. Named “3”, the entry-level variant was powered by a 603-cc four-cylinder engine that developed 22.5 horsepower. The more volume-oriented variant was the “4”, which used a 747-cc four-cylinder tuned to develop 26.5 horses. Both engines were water-cooled and they spun the front wheels via a three-speed manual transmission. Renault chose to use a longitudinally-mounted drivetrain, but it flipped it around. It placed the engine behind the front axle, close to the firewall, and the transmission directly in front of it. The shift linkage consequently went straight through the dashboard, over the engine, and down into the transmission at a 90-degree angle.

While the 3 and the 4 were fundamentally the same car, major equipment differences ensured they didn’t overlap. Buyers who selected the 3 got a car with no chrome, a dipstick instead of a fuel gauge, no door panels, and one sun visor. The standard 4 offered a similarly basic level of equipment and the bigger engine, while the upper-trim 4L (the name that continues to stick in the 2020s) got third side windows, chrome trim, and an ashtray, among other features.

Renault quickly expanded the lineup. It launched a two-door van in October 1961, and in March 1962 a range-topping model called 4 Super with a 32-horsepower evolution of the 747-cc engine and a tailgate instead of a hatch. Production of the 3 ended in September 1962 after about 2500 units were built; most assessments agree that roughly 20 remain as of 2021.

Growing up and branching out

While the 3 was a dud, the 4 was an instant superstar. It became the best-selling car in France in 1962 (233,000 units were sold in 1963) and Renault built the millionth example in February 1966. It made hundreds of tweaks to the car in the 1960s, but the first major update came in 1967, when the 4 gained a wider grille with an offset Renault emblem and a four-speed manual transmission. Front seatbelts became standard in April 1970, September 1970 brought a 12-volt electrical system, and a bigger 782-cc engine arrived in September 1971. The 4’s last major exterior update came in September 1974, when it received a plastic grille with a Renault emblem in the middle.

Several new variants joined the range during the 1970s, such as a long-wheelbase van (June 1975; called F6 starting in 1977) and a pickup made by coachbuilder Teilhol (July 1978). Significantly, the 4 GTL made its debut in January 1978 with a 1.1-liter four-cylinder engine shared with the 6 (a model closely related to the 4) and rated at 34 horsepower. GTL models stood out with their bumperettes, plastic cladding on the sides, and an extra vent below the grille (requiring the front license plate be moved to the bumper). The GTL, from its launch in’78, gave sales a healthy initial boost.

Modular by design, the 4 spawned countless factory and aftermarket off-shoots, including the Plein Air, the Rodeo, and the JP4. Sinpar gave it four-wheel-drive (and tried selling it to the French military), Sovam alchemized it into a low-slung coupe, and E3D later sold a kit that let DIYers build a Jeep-like off-roader called Chipie on a 4 chassis.

Easing into retirement

Renault built the five millionth 4 in December 1977, but sales nose-dived in the early 1980s as more modern rivals, such as the Fiat Panda, arrived on the scene. Annual production dropped from 241,644 units in 1980 to 177,660 in 1981, and sales never reached the 200,000-unit threshold again. Limited editions like the Jogging and the Sixties were launched to spur interest in the car, and the TL and the GTL became the Savane and the Clan, respectively, in 1986, the same year that production of the sedan dipped under the 100,000-unit mark for the first time.

Regulations compounded the 4’s problems. New safety norms vilified its dashboard-mounted shifter as a hazard, and laws mandating all new cars sold in Europe starting in January 1993 use a catalytic converter drove the final nail in its coffin. Renault released one final limited-edition model named Bye-Bye in 1992. Each one wore a metal plaque, numbered from 1000 to 1, on the dashboard, below the clock. Renault kept the final Bye-Bye, but it’s not the last-ever 4. Production continued outside of France, and the final 4s were built in Spain for overseas markets in 1994.

The Renault 4 in 2021

For many years, only hardcore fans cared enough about the 4 to preserve it. Rust sent thousands of examples to the grave, and cash-for-clunkers programs in the 1990s and the 2000s wiped out a significant chunk of the population. 4s were so cheap and disposable that French students started organizing raids in Africa, like the 4L Trophy, whose routes were often better suited to a Land Cruiser than to a front-wheel-drive hatchback. Some were adequately prepared for the adventure, and they survived. Many were not, and they were utterly destroyed in about a week.

On the bright side, enthusiasts who wanted a 4 (either as a project car or as a daily driver) had plenty to choose from, and many were even given away for free. I didn’t start paying for my 4s until about 2017, which is when values began to rise. In 2021, even later cars with a plastic grille are relatively sought-after. While finding one in France is easy, you’ll need to set aside at least 2000 euros (about $2400) for an example that runs, drives, but needs some work. Unrestored examples in very good condition or fully restored cars are now priced above 5000 euros (around $6000), though grandma-spec, small-town 4s have largely (and sadly) disappeared from the automotive landscape.

Later cars—especially GTLs—make excellent daily drivers. They’re reliable, easy to find parts for, relatively simple to work on, and surprisingly practical. Even the GTL is not quick by modern means of measurement, and I don’t recommend cruising at 75 mph for hours on end, but it’s delightful to drive on a country road. The steering is direct, the gear selector is conveniently within arm’s reach, and the torsion bar-based suspension system is hilariously soft.

The 4’s legacy

Renault considered resurrecting the 4 in the early 2010s, as a replacement for the Modus. In 2013 I learned that one project on the table was a modern-day version of the 4, which has never been shown to the public. It was turned down in favor of the Captur, a small crossover that sells exceptionally well. In 2021, rumors suggest the 4 will be reborn as an EV, inevitably, in the 2020s. Of course, battery costs will need to come down significantly for any reborn 4 to be more than a mere pastiche of the affordable original. Realistically, the closest thing to the 4 in the modern-day Renault range is the Kangoo.

Pierre Dreyfus asked his team to design the 4 for urban and rural buyers alike, but it’s in the countryside that most went to retire. Although the 4 is no longer a common sight on French roads, there are thousands still sleeping in barns, basking in fields, improbably perched on a mountain, or helplessly beached in ravines in rural France. Some were turned into trailers; others became chicken coops. Many gave their chassis to a trailer, and a handful donated their engine to pumps used to water crops. Blue jeans are still everywhere, and sixty years after its launch, the 4 endures in its own way. Long may it live.