Media | Articles

The jerrycan design goes back over 80 years, and it’s showing no signs of retirement

Now and again, an invention becomes so ubiquitous that it’s rendered practically invisible. An industrial designer might consider that the ultimate compliment—a bellwether for a product’s longevity. All this was running through my brain when I recently had to explain to a friend what “that red thing” was, and what purpose it served. Really, when’s the last time you thought especially hard about the humble jerrycan?

In defense of my friend, who is far from dense, the jerrycan is obsolete as far as most urban-dwelling people are concerned. In the modern city, fluids simply gush from the tap or flow from a nozzle, rarely requiring a second thought. Not everyone can fathom that potable water is still in short supply for many populations in developing countries, or that transporting fuel safely can be a matter of life or death.

War has a powerful, almost unparalleled influence on driving innovation. The jerrycan has its roots in Germany, where it was conceived, mass-produced, and stockpiled beginning in 1937 for the impending conflict between nations. At the time, the invention was anything but invisible to American engineer Paul Pleiss, adherent of the all-important axiom that recognizing a great idea is equally as important as having one.

Pleiss worked for Ambi-Budd Presswerk (ABP), a German auto body manufacturing company and extension of a Philadelphia-based industrial outfit called the Budd Company. Pioneered by titans Edward G. Budd and Arthur Müller, ABP set up shop in Rumpler’s old Berlin factory where it specialized in pressed-steel technologies used for making BMW and Ford bodies. When war seemed imminent, ABP pivoted into operations concerning military needs, including bodying the iconic light-duty Kübelwagen and Schwimmwagen. The company’s side project—developing one of the first jerrycan designs—was perhaps even more influential, even if it at the time wasn’t officially recognized.

Hitler made mastery of liquid transport a priority, tasking Germany to devise a rigid and robust unit of storage that could withstand wear, pour well, stack conveniently, and carry easily. Müller, in addition to his ownership stake in ABP, was involved with a German-based engineering firm called Müller Engineering that was also working on the jerrycan project. In 1937, Vinzenz Grünvogel, chief engineer at Müller’s namesake firm, was awarded official credit for the creation of the Wehrmacht-Einheitskanister (Armed Forces Unit Canister), but it’s easy to see a through line from Grünvogel’s final design to Müller’s investment in ABP.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Pleiss, the American, recognized immediately the significance this new type of efficient liquid transport held for Germany. The jerrycan was superior in every way to the outdated American cans adopted from the WWI-era and infinitely more practical than the British “flimsies”—British low-grade four-gallon cans made of tin. The name was apt.

Richard M. Daniel, a retired WWII U.S. Naval commander and chemical engineer, recounted the merits of the German design on jerrycan.com:

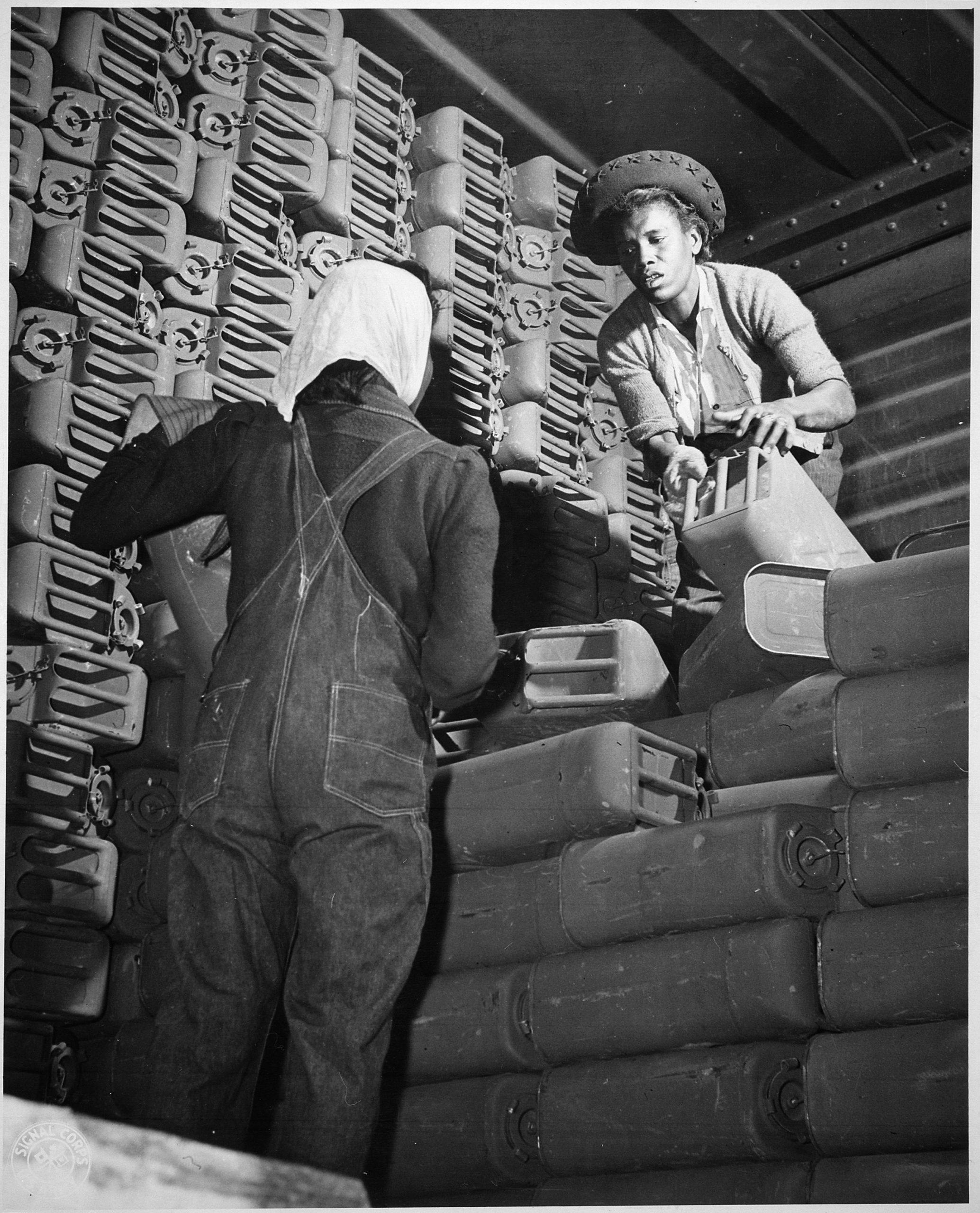

“It was flat-sided and rectangular in shape, consisting of two halves welded together as in a typical automobile gasoline tank. It had three handles, enabling one man to carry two cans and pass one to another man in bucket-brigade fashion. Its capacity was approximately five U.S. gallons; its weight filled, forty-five pounds. Thanks to an air chamber at the top, it would float on water if dropped overboard or from a plane. Its short spout was secured with a snap closure that could be propped open for pouring, making unnecessary any funnel or opener. A gasket made the mouth leakproof. An air-breathing tube from the spout to the air space kept the pouring smooth. And most important, the can’s inside was lined with an impervious plastic material developed for the insides of steel beer barrels. This enabled the jerrycan to be used alternately for gasoline and water.”

This level of detail and practical consideration was light-years ahead of anything the Allies had in this arena. By the time war broke out in 1939, the Allies would have had to dedicate a Herculean effort to produce a comparable piece of equipment. That’s when Pleiss entered the picture.

As the story goes, it all started with a road trip in early summer, 1939, right before the outbreak of European conflict. Pleiss and a fellow ABP engineer planned to embark on a journey across Eastern Europe and the Middle East, beginning in Berlin and ending in Eastern India, riding in a purpose-built vehicle. The problem? They were short on fluid storage. The quick fix, naturally, was to appropriate three examples of Grünvogel’s Wehrmacht-Einheitskanister from the nearby Tempelhof Airport before departing Berlin. The pair promptly secured the canisters to the underside of the rig and rode off with a few choice examples of intellectual property.

When war broke out, Pleiss’s German traveling companion was called back into service. Suddenly, the American was left to his own devices with a great frontier ahead of him. Before flying home, his friend allegedly slid him the comprehensive design plans. When Pleiss managed to Calcutta following what must have been one hell of an adventure, he stored their custom-prepped rig—jerrycans included—and flew back to the U.S. with the plans in hand. Afterward, he’d arrange for the vehicle to be shipped with the cans still attached safely underneath.

For whatever reason, the U.S. military did not latch onto this German innovation with immediate gratitude. The Brits, on the other hand, took to Pleiss’s revelation with great enthusiasm. They’d confiscated many of the cans after the Germans began to invade Norway, and it didn’t take long until British servicemen coveted the German invention as the gold standard of liquid transport. It’s at this point that the Wehrmacht-Einheitskanister ostensibly picked up its lingua franca name of “jerrycan.” As the Brits got the jump on producing replicas, the American military authorities remained steadfastly unconvinced.

It took several clever pleas to move the needle. Here’s Daniel again:

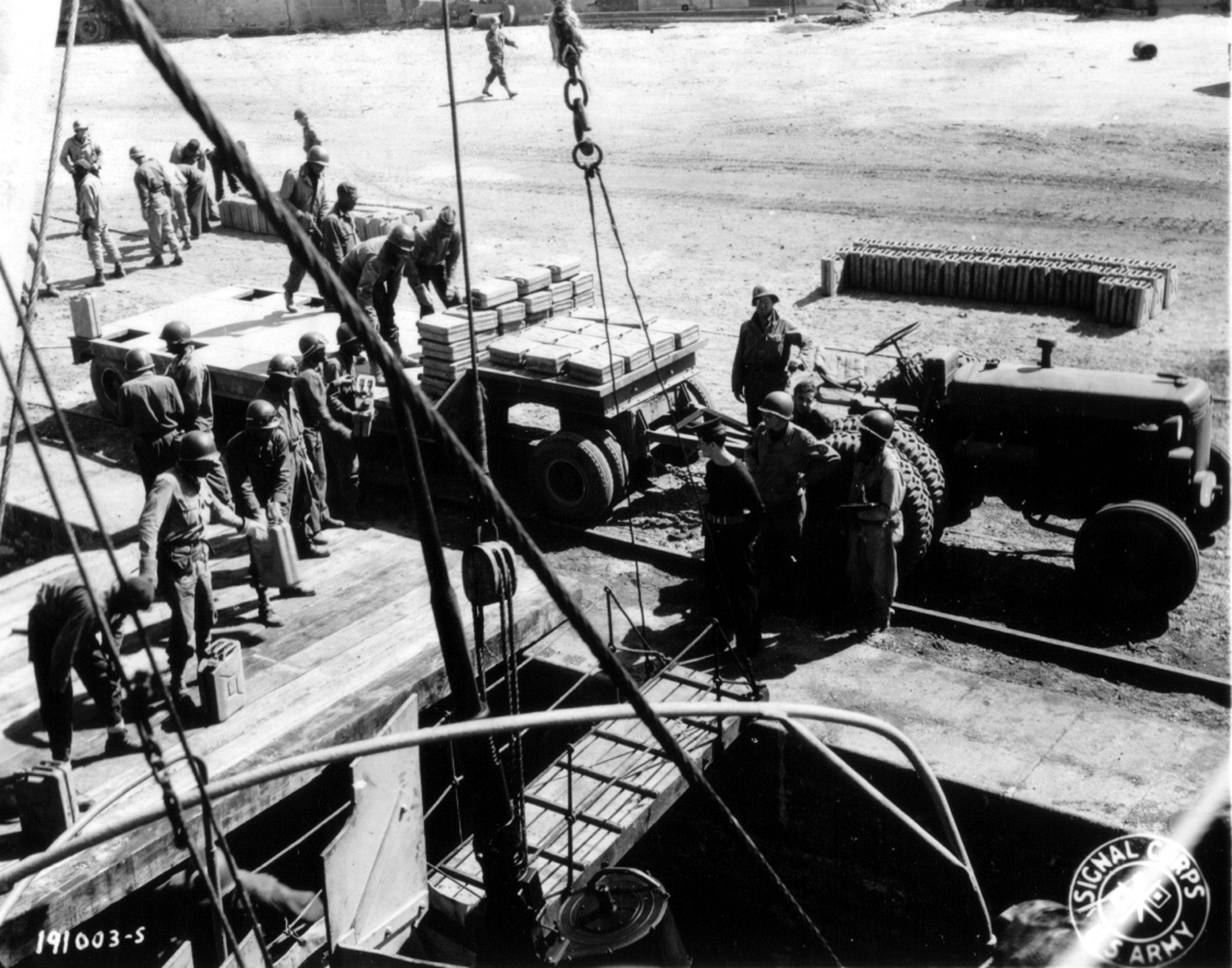

“My colleague and I learned quickly about the jerrycan’s advantages and the Allied can’s costly disadvantages, and we sent a cable to naval officials in Washington stating that 40 percent of all the gasoline sent to Egypt was being lost through spillage and evaporation. We added that a detailed report would follow. The 40 percent figure was actually a guess intended to provoke alarm, but it worked. A cable came back immediately requesting confirmation.

We then arranged a visit to several fuel-handling depots at the rear of Montgomery’s army and found there that conditions were indeed appalling. Fuel arrived by rail from the sea in fifty-five-gallon steel drums with rolled seams and friction-sealed metallic mouths. The drums were handled violently by local laborers. Many leaked. The next link in the chain was the infamous five-gallon “petrol tin.” This was a square can of tin plate that had been used for decades to supply lamp kerosene. It was hardly useful for gasoline. In the hot desert sun, it tended to swell up, burst at the seams, and leak. Since a funnel was needed for pouring, spillage was also a problem.”

It wasn’t until early 1943 that the British finally pumped out 2 million competent jerrycans for wartime use. In the meantime, battles continued to be fought and lives lost. By early 1944, the Americans and the rest of the Allies were finally on board. By this point, the Brits possessed all the necessary means to manufacture a jerrycan rivaling the German original. Roughly five years from the time Pleiss and his German friend passed through the Middle East on their way to India with three stolen jerrycans on board, a British factory in the Middle East was making millions of jerrycans destined for Allied forces.

We hear a lot about the tanks, automobiles, and weapons that helped turn the tide of this gargantuan international crisis, but the simple jerrycan doesn’t exactly get a lot of airtime on History Channel. Nevertheless, jerrycans carried the fuel and water essential for wartime operations, and the same basic design remains in use today throughout public and private sectors. The term has grown to include a family of cans differing in size, shape, and color, but their essential function remains intact. Next time you’re out overlanding and see a jerrycan strapped to the roof of a 4Runner, it might not seem so invisible.

Thanks for the article; I’m always intrigued by the stories behind things that are taken for granted.

For the last 35 years or so, I’ve used the plastic JAZ racing fuel jugs for refueling: a vast improvement over the jerry can, being lighter, more user-friendly, and spill-proof with a proper outlet, which are usually filtered.

This is the first time I recall WW II being referred to as an international crisis.

Unfortunately that’s exactly what it was. There was not 1 country on the planet that wasn’t negatively affected by the war.

There are some great You-Tube videos on the topic, but this is by far the best and most concise written discussion I have seen. Nice work!

I had a cheap imitation of one of these. It had no spout, the cap screwed into the body, and it was unlined. One bought a separate spout that replaced the cap when fueling. Since it was unlined, condensation tended to collect inside and pool at the bottom of the can. I tossed it out after a few years.

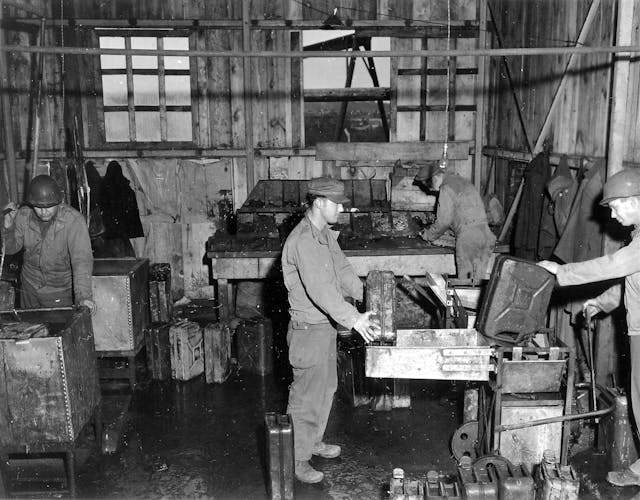

The first photo from the national archives purporting to be of welders is an obvious propaganda shot. These guys are holding the welding rods in their bare hands. They wouldn’t do that for very long in the real world.

Actually it’s easiest to hold the filler rod with bare fingers when gas welding. It’s too thin to manipulate confidently with gloves on, and being steel it’s consumed far quicker than heat can travel through it. None of this means it’s not still a propaganda shot though.

You would be surprised what those people used to do. After a while they were numb from heat. I had friends from that Era who worked as machinists. The screw machines that use to put the thread on screws and bolts, each piece that was completed they had to remove from the machine and run their fingers along the threads to make sure the threads were OK and deep enough, they did that bare handed and if you know about machine processes like lathes grinders and screw threading machines parts come off hot. Needless to say they became numb to heat as well. Now days the took care of that by making go-no go gages, were they run the threads into this thing which would tell them if the threads are ok or not. I am sure that they could have made the same thing back then but because of the war effort they could not spare the metal.

Plastic jugs inevitably leak at their seams and whatnot. I have two Jerrycans to use when I want to store larger than a gallon and I swear by them.

Did you know that they are stamped and date-coded on the bottom? Mine say “USMC.” Go, jugheads!

US made Jerrycans were in wide use by 1941. I have several. USMC marked cans were made by US Metal Can if I recall correctly. For more information check the Jerrycan forum on G503.com.

https://forums.g503.com/viewforum.php?f=37&sid=be229b41a88279946fed9cd447e5046b

After the war my father worked for the Van Leer oil drum factory and with their expertise in pressed steel they also produced jerrycans. He had one of them kept in unwelded two halves but hinged on one side and the other with locks and the inside nicely dressed in velvet lining. And so he carried his papers in this briefcase to meetings to appreciative acclaim: great PR !

Joseph DeMeyer

PS : didn’t know Hitler had-another- transportation- legacy..

It really was one of the greatest advancements, just a simple device to carry fuel safely.

Sadly I expect emissions regs to kill them.

California has already killed them. You can’t even sell a race jug there with out a million dollar fine.

Others are doing the same. It is sad you can not just buy and use a simple can anymore. I got mine from yard sales wile still available.

Great article!

I’m 85 and my family fab. shop bought tons of stuff including vehicles at post WW2 auctions. I still have some Jerry cans in use. Some have a threaded opening with what I would call a screw in plug instead of cap. Flexible metal poring spouts were threaded into this opening. Have some of those also.Others were designed as water cans with a hinged and cam locked lid or cap and is cam locked. the inside is coated with a light colored slick material that kept water potable. Maybe I should do a search and see what they are worth.