Media | Articles

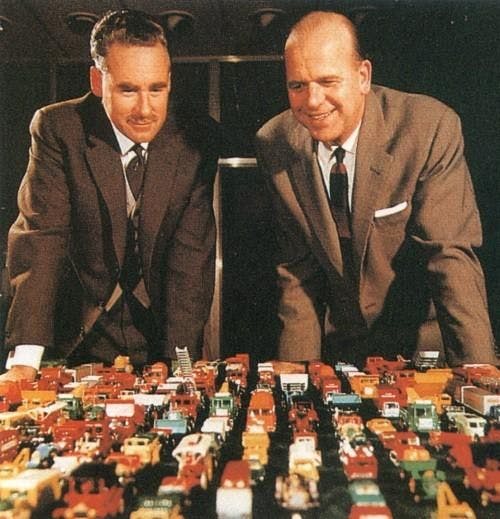

Jack Odell and Marcel Van Cleemput: Big men in little cars

Many of you who are reading this have some kind of die-cast model of a car or truck within eyesight of where you are sitting. The story of die-cast model cars and trucks probably goes back to prehistory, when the inventor of the first wheel very quickly realized that he could amuse (and occupy the time of) his young, prehistoric offspring with a miniaturized facsimile of that invention.

The modern history of die-cast models traces to a development not in toymaking but rather in printing newspapers. From the times of Gutenberg until the late 19th century, printing involved laborious hand-setting of the print type, and most model vehicles were carved of wood or, when industrial stamping was developed, pressed out of sheet metal (hence “tin toys”) and decorated with photolithography. In 1884, one Ottmar Mergenthaler patented what he commercially introduced at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair as the Lin-O-Type machine, essentially a self-contained, semi-automated die-casting foundry that allowed newspaper publishers to set type as quickly as new “extra” editions demanded. The Lin-O-Type was in use for almost a century.

Until the development of die-casting, toymakers generally cast small toys out of lead, using the “slush” casting method to create hollow molded toy soldiers and the like. With die-casting, a low temperature melting alloy is forced under pressure into the voids inside a two-part die—pretty much injection molding only with metal and not plastic. The invention of the Lin-O-Type allowed all sorts of small products like sewing notions and toys to be mass produced very inexpensively, with very fine details, as the casting reproduces every fine shape and line in the dies. One of the earliest applications outside of typesetting was to make the trinkets used as play pieces for the Monopoly game. Soon, model train, car, and truck makers realized they could execute greater detail with cast bodies than with stamped tin or steel.

In 1879, a bookkeeper named Charles Dowst and his brother started publishing a trade publication named The National Laundry Journal. They were early adopters of the Lin-O-Type machine for their publishing company but soon realized they could also use it to make the small items like buttons, cufflinks, and promotional items used by laundry operators.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In 1911, a few years after Sam Dowst’s son Theodore joined the company as a clerk, it introduced its first toy car, a tiny limousine cast of lead. Ten years later, the company started using the TootsieToy brand for a line of dollhouse furniture and miniatures. Apparently that was how Ted Dowst secretly acknowledged his daughter Catherine, with his nickname for her, Tootsie, despite Sam Doust’s strong disapproval of the child’s birth out of wedlock to one of Ted’s secretaries at the family firm. Her parents only married after her paternal grandfather passed away. Soon, the Dowst catalog listed a number of model vehicles under the TootsieToy brand, including a well-selling, scaled-down Model T Ford.

Meanwhile in England, the Hornby company, maker of model trains and the Meccano line of what we in the United States call “erector sets,” started selling a line of slush-casted Modeled Miniatures as accessories to their trains, including “Motor cars,” “Racing cars,” and commercial vehicles. Soon they were branded Dinky Toys and were a big success in the UK.

The Dowst TootsieToy cars and trucks were originally simple one-piece bodies, wheels included. Later they made rolling wheels with axles press-fit into stanchions cast into the bodies. In the early 1930s, the company patented a two-part method of construction where a uniform base with fenders and individual body styles were cast separately and joined together with the model’s axles passing through matching holes in the two parts. The axles were essentially nails or rivets, with the pointed end flattened to secure the wheels and lock things into place. Until Mattel’s Hot Wheels were introduced, with their low-friction wheels spinning and suspended on piano-wire axles (well, guitar strings according to legend), that was the standard way small model cars, trucks, and motorcycles were made.

The standardized base made for efficiencies and the way the two cast-metal parts fit together resulted in a toy that could live up to a lot more abuse than stamped metal or even the previous way the company made die-cast models. They were also made of Zamak, a new zinc-based alloy that was strong and reproduced designs in fine detail. Made in O-scale, the same as Hornby trains, the British company must have taken notice of the TootsieToy cars. Perhaps to preempt the Dowsts from establishing intellectual property rights in the UK, the Meccano brand introduced a line of O-scale model cars that pretty much copied both the exterior designs and the construction method of the TootsieToy vehicles. When the TootsieToy company decided to concentrate on simpler, less-expensive ways to produce models as the Great Depression years went on, Dinky was able to establish itself in the United States.

Although die-casting was new when TootsieToy and Dinky Toys were being developed, by the 1940s it was an established industry. After the end of hostilities in the Second World War, there was a boom in demand for consumer products and the end of war production meant there was plenty of modern industrial equipment and trained engineers and technicians. In 1947, two unrelated schoolmates, now veterans of the Royal Engineers and the Royal Navy, Rodney and Lesley Smith, decided to pool their mustering out benefits and start a company. Rodney was working at Die Casting Machine Tools Ltd., while Leslie had held a series of sales jobs or working in construction for his father. They gathered up 500£, rented a decrepit old pub for less than 10£ a month, and bought a hand-operated die casting machine from Rodney’s employer. They called their company Lesney Products, after their two names, and because they didn’t know exactly what they’d be making.

Enter Jack Odell, a friend of Rodney’s who stopped by the pub one morning. Odell was a bit of a non-conformist and had been making his way in the world since being expelled from middle school at the age of 13. He drifted from job to job until he found his métier in engineering. His day job was stripping military surplus vehicles and selling off the parts, but he had wanted to start a side die-casting business with six ex-army casting machines he’d picked up for just 60£ total. Unfortunately, the local town council wouldn’t let him set up shop in his mother’s residential basement, so he approached the Smiths about a three-way partnership. The fact that Odell had an order in hand for a few thousand die-cast string cutters, then in wide use by retailers tying packages shut, probably smoothed the negotiations. The orders for the string cutters and then a contract for parts for General Electric helped establish the Lesney firm, but it was when the company received an order for some toy guns and handcuffs from a local dartboard maker during a slow period that it realized the potential in making and selling toys.

Odell had a creative side, so he designed three well-proportioned and finely detailed models of a road roller, a cement mixer, and a Caterpillar tractor made with and without a bulldozer blade. At just a third of the price of Dinky models, and sold in mass market chains like Woolworths (which Hornby had disdained in favor of specialty toy stores), the Lesney models were successful enough to help put the new firm on sounder financial ground. In 1949, they reorganized as a proper limited corporation and moved out of the pub into an actual factory in east London. In advance of the 1951 Festival of Britain, planned to be a huge celebration, Odell designed an intricate model of the horse-drawn Royal State Coach, scheduled to be used in high profile at the Festival. The Korean war, however, intervened, making it hard to get zinc, so the project was literally tabled; Odell kept the molds under his desk. That same year, Rodney Smith decided to cash out, selling his third of the company to the other partners.

When King George VI died in 1952, they dusted off the dies for the Royal Coach, planned to be extensively used in Elizabeth II’s 1953 coronation ceremonies, and ended up selling 33,000 of them, a modest success. Odell then executed a beautiful, even more miniaturized version, just four and a half inches long, small enough to be held in one’s hand, with the detailed coach cast in brass and the eight lead horses hand painted. Sold through gift, candy, and novelty stores, over a million were sold. For the 2023 coronation of King Charles, who used the same carriage as his mother did and British monarchs have for centuries, the Matchbox brand, owned since 1997 by former competitor Mattel, issued a new version of the Coronation Coach. I won’t call it a “reissue” because they didn’t use all of Odell’s original design but rather they recreated the carriage the way models are done these days, with multiple photographs of the actual gilded carriage in the Royal Mews, making it actually more accurate than Odell’s model. Perhaps as an homage to him, though, the new horses were created starting with 3D scans of Odell’s original animals.

Odell and Smith realized that there was big money in small items, leading to the creation of the Matchbox brand, Dinky’s first serious competitor in die-cast models. The idea had its germination in a teacher’s rules. Odell’s daughter Anne had a teacher who let her students bring toys and other objects of curiosity as long as they could fit in a matchbox. Anne decided that worms and spiders were a perfect fit, leading to some annoyance of Jack. He told her that if she would stop doing that, he would make her a toy that could fit in a matchbox. She agreed. O’Dell then scaled down the Aveling-Barford road roller that he had earlier made, crafted it out of brass and then hand-painted it green and red. She took it to school and when her father picked her up in the afternoon, he was swamped by her classmates clamoring for their own copies.

Odell proposed to his partner Leslie Smith that they make a series of die-cast toys small enough to fit in a matchbox (specifically the ones made by the Czech firm, Novic Match Company, that he had in his pocket). Smith and their wholesale distributor Richard Kohnstam recognized the opportunity to expand their sales outlets to tobacconists and other corner shops where parents could purchase the relatively inexpensive toys as an impulse item and the Matchbox Series was launched with the road roller, a Muir Hill Site dump truck, a cement mixer, and a Massey-Harris tractor. They were soon joined by what would become a perennial Matchbox model, a double-decker London bus. When the bus started selling well, retailers who formerly disregarded the relatively inexpensive toys took notice. The fact that they were sold as a series, with more models to come, meant they were more than impulse items, they were collectibles.

While generally known as “Matchbox cars,” the historical reality is that the Matchbox brand was on sale for more than two years before it offered an actual car, No. 19, an MG TD, and No. 22, a Vauxhall E. Die-cast model makers have since tried to strike a balance between sports cars that children aspired to own when they grew up, and more familiar sedans like the family car might be, along with commercial and construction vehicles they could incorporate into their play. Regarding the construction and commercial vehicles, Odell seems to have tried to make them all functional in some way, like the original road roller’s pivoting front wheel or a bulldozer with a working blade.

Jack Odell was a man of many talents. While Smith ran the business side of Lesney, O’Dell didn’t just design the company’s original model toys, he also engineered the production equipment to make them, including one of the first automated die-casting machines and the factory’s transfer machinery. It was also O’Dell’s idea to introduce Matchbox’s Models of Yesteryear range in 1956, with scale models of vintage automobiles. Odell realized that while kids might not be interested in pre-war machinery, there were millions of potential adult customers wanting to relive their youth, an idea that continues to support the die-cast model industry. It’s not kids who follow trucks to Walmart so they can get first crack at new Hot Wheels models.

By the mid-1960s, Lesney was the fourth-biggest toymaker in Europe, with millions of pounds of profits every year. For a business that started in the basement of an abandoned pub, they did pretty well for themselves.

While Lesney thrived, Dinky stagnated, and soon there’d be a new competitor that took realism to a new level, Corgi. As at Lesney, the man that seems most responsible for that brand’s success was not one of the founders. And just as Matchbox was a brand of toys sold by a company with a different name, Lesney, the Corgi brand was a product of a company called Mettoy. In 1956, the Corgi brand exploded onto the diecast model scene with a feature neither Dinky nor Lesney had, clear plastic windows on their cars. What seems like a rather mundane thing today was a leap forward in authenticity and realism. Later, Corgi would add injection-molded interiors, working steering, and other realistic features.

Mettoy was founded in the 1930s by Phillip Ullmann, who had built up a successful maker of tinplate, clockwork toys called Tipp & Co. over the course of two decades in Nuremberg, Germany. Ullmann, who was Jewish, fled Germany for the UK when the Nazis came to power in 1933. With his connections in the toy business and the assistance of his South African cousin, Arthur Katz, he quickly established Mettoy as a force in the British toy industry, and by the outbreak of WWII the company employed over 600 people at its factory in Northampton. Mettoy’s expertise working with metal made it a valuable contributor to the war effort, and it was so successful at it that the defense ministry allocated the company a brand new factory, with modern tooling and equipment, in Swansea. After the war, Mettoy expanded that plant and brought out its first line of die-cast cars, a Standard Vanguard and a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith. It was Howard Ullmann, Phillip’s son, who came up with the name Corgi. Perhaps intentionally meant to sound similar to Tootsie and Dinky, the brand name was definitely a nod to Queen Elizabeth’s favorite dog breed.

In 1954, Ullmann and Katz hired a 28-year-old engineer named Marcel Rene van Cleemput. Though born in France, van Cleemput grew up in Yorkshire and earned his engineering degree in the UK. Following his national service in France, he returned to England, where he worked for six years at an elevator company. With those beginnings one might not have expected him to have an impact on the world of toy cars, but it was van Cleemput who brought realism to the die-cast world.

Though he had no experience in either toy or car design, within six months of hiring in, van Cleemput was made chief designer.

“The first thing I was asked to do was design a little mould for part of a [toy] duck. Now, I’d never even thought of a mould before. I didn’t know what a mould was because I had been in lift [elevator] design, press tool design, and jig and tool design. But anyway, I caught on, and within six months I was chief designer. I did the drawings for the very first one and then I was involved in every single Corgi model that was ever produced until the company went bust in ’83. Probably 95 percent of the models emanated from myself … The pressure was there because we did two or three new models per month, and if each one had 20 parts then we had to produce 20 drawings and then we had to produce the moulds for each model as well—each little block of steel in the mould had to be detailed, fully dimensioned; there’s a lot of work.”

It was Cleemput who figured out that in order to make models look more realistic to those playing with them, they couldn’t be exact scale models, something designers of actual automobiles realized when scaling up designs from smaller clay models. Not all proportions scale well. Actual cars are designed to be looked at from street level but children playing with toy cars usually are looking down on them, and when done to actual scale, the passenger compartments could look a bit cramped. Adding a few millimeters to their widths counterintuitively made them look more realistic than when accurately scaled.

While the model cars were getting more realistic, it was in embracing the world of make believe that Corgi had its biggest hits. One of Peter Katz’s responsibilities was being regional sales manager for Scandinavia, and Katz was excited to be able to promote the Volvo P1800 that Corgi had introduced in mid 1962. One of his wholesale customers told him that the detective show The Saint, starring Roger Moore, was very popular in Sweden. Moore’s character, Simon Templar, drove a white P1800 in the British television series, perhaps because for the first two years of that model’s production, it was made in the UK, with bodies produced by the Pressed Steel company and final assembly by Jensen. By simply adding The Saint’s “stickman” logo on the bonnet/hood and a plastic driver that vaguely looked like Moore, sales of the model quadrupled from about 300,000 units a year to more than 1.2 million.

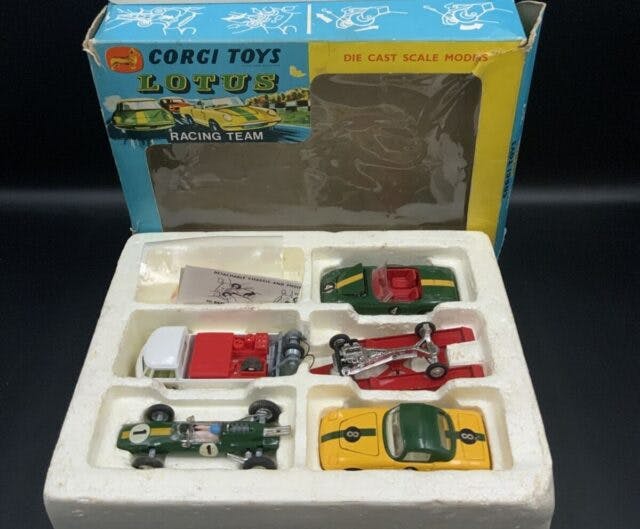

When the producers of The Avengers television series put Emma Peel in a Lotus Elan, Corgi similarly already had an Elan in production, which they put in a gift set with John Steed’s Bentley, complete with spare plastic umbrellas for the Steed character behind the wheel. The set was so popular that you can still buy reproductions of the Peel and Steed characters.

To give you an idea of the kind of realism that Corgi chased under van Cleemput’s direction, the Elan was also available as part of a multi-vehicle racing set, with a Lotus open-wheel racer and a VW Combi pickup as a tow vehicle. The Elan in real life has all of its mechanical components mounted on a backbone frame to which the one-piece fiberglass body is mounted. The Elans in the racing set have realistically appointed chassis that can be separated from the bodies with a spring release. The set even includes a spare chassis.

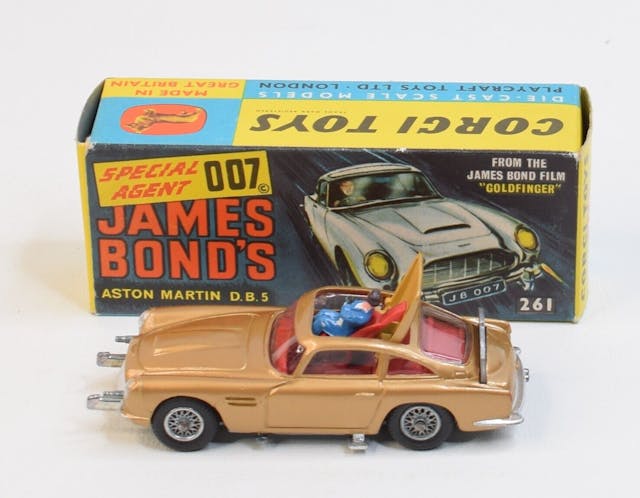

Perhaps the greatest hit for Corgi in its heyday was the James Bond Aston Martin DB5. Van Cleemput remembered someone giving brand manager Howard Fairbairn a September 1964 newspaper with photos of the spy’s car in the soon-to-be-released Goldfinger and suggesting that they “should get on to it quickly.” Fairbairn initially rejected the idea, believing the cars’ gadgetry to be too complicated to reproduce scaled down. When the movie turned out to be a global hit, Fairbairn changed his mind and made it the company’s number one priority.

Though van Cleemput often gets much of the credit for the Bond model car, and while undoubtedly he had some role in the development of the Bond DB5, the model and it’s workings were actually the products of designer Tim Richards and project leader John Marshall.

In a 2017 interview, Richards said, “They suddenly said yes and all hell broke loose; everything else was put on hold. The film was already out and they’d really dragged their heals on it. We already had an Aston Martin DB4 in their Corgi range and I had to modify that into a DB5 and make a resin mould mega-quick. It was a botch job, to be honest.”

Making a DB5 out of a DB4 was one thing, but what made the car one of the stars of the movie was its array of villain-defeating gizmos. It was decided that three “must haves” were an ejector seat with an opening roof panel that Bond uses in the film to dispatch a North Korean adversary, a pop-up bulletproof rear shield, and bumper guards that flip open to reveal machine guns. Marshall designed the ejection mechanism as well as the other two features, triggering them with hidden actuators. Along with the ejectable villain, the car also came with a Bond figure, Walther PPK already in hand. A total of eight patents were granted on Corgi’s Bond DB5, with about 30,000 man hours invested in the project.

In a departure from realism, the model car was painted gold, unlike the silver car in the movie, as Corgi personnel decided the silver car looked unpainted. Even though the model was released in October 1965, almost a year after the film’s debut, it sold over 750,000 units in less than three months, going on to sell over 4 million examples. In 1968, Mettoy upgraded it with swiveling license plates and tire slashers, and painted it silver this time, and that sold 1.2 million copies. The Corgi Bond DB5 has been so popular that it has stayed in production as the company has changed hands and gone through a bankruptcy. It was even reissued in 2021, in connection with the then-latest episode of the James Bond movie franchise, No Time To Die.

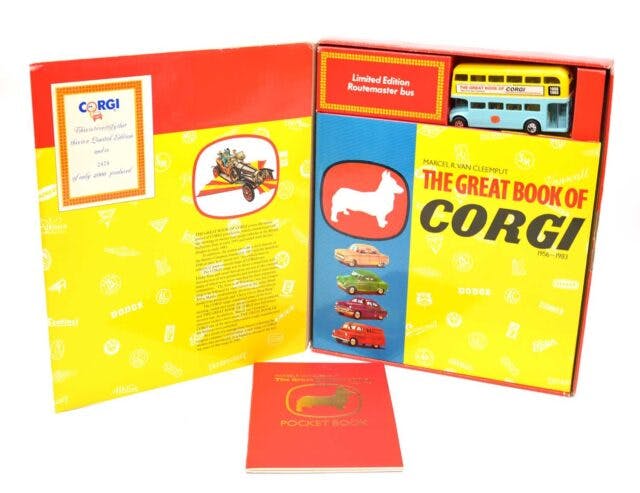

It’s not surprising that histories sometimes mistakenly credit Marcel van Cleemput with the Bond car. In the quote above, he mentions how he had a role in every Corgi model made from 1956 to 1983, and some have exaggerated that to say that he designed every Corgi model made for almost 20 years, to the chagrin of some of his associates at Mettoy. Although he may not have actually designed every Corgi model, he was certainly the brand’s most important figure outside of the company’s founders. Van Cleemput’s contract with Mettoy guaranteed him one example of every Corgi model that was made, so by the time of Mettoy’s bankruptcy he had the largest collection of Corgi models anywhere. That collection was the basis for van Cleemput’s The Great Book of Corgi, a guide to every model Corgi made during his tenure there. The book has gone through two editions and is now more collectible and more valuable than many of the Corgi models he designed, fetching hundreds of dollars per copy, particularly if it still has the limited edition London bus Corgi released for its publication.

The names Odell and van Cleemput aren’t nearly as well known as the Matchbox and Corgi brands, but wherever they may be, they probably don’t mind. Odell was a millionaire in his 40s and was made an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Queen Elizabeth, whose coronation coach he commemorated. Van Cleemput was literally known as “Mister Corgi,” his book is the standard reference on the history of Corgi models, and he was so important to the brand that histories often credit him with more than he actually did.

Jack Odell died in 2007, and Marcel van Cleemput passed away in 2013. Perhaps more important than any honors or awards they might have received in their lives, their true legacies are that they enriched the imaginations of millions of children and helped create and grow a hobby that continues to enrich the lives of millions of adults.

One area often over looked are first the Rubber cars of the early 20th century. These were made by companies like Sun Rubber and were very popular in the depression. They were lower cost for the era when it was hard to feed a family vs buying toys.

Later on companies like Processed Plastics and Gay Plastics reproduced cars in larger sizes at a low cost that was sold by stores like Kresge and Woolworth.

I have a few of all these types some from when I grew up and some I purchased later to replace the ones I had as a child.

Quite the complete history you’ve given us, Ronnie. Great job!

The specialty Corgi models were my favorites: the Bond car, the Batmobile and Green Hornet’s Black Beauty.

I still have the original-issue Batmobile, if anyone’s interested in it.

https://longisland.craigslist.org/clt/d/bellport-original-issue-corgi-batmobile/7676551474.html

Great story and great model cars.

My grandpa had the Corgi Bond car when I was little in the 60s, I was always confused that it didn’t say “Matchbt by Lesney” on the bottom….And I strongly recommend everyone watch that Lin-O-Type video. What a triumph of engineering and machine work!

“Matchbox by Lesney”…thanks for nothing (relatively) new platform that doesn’t allow edits…

Any info on Howard Fairbairn please, my family was related and are trying to trace his other family members

” The model car was painted gold, unlike the silver car in the movie, as Corgi personnel decided the silver car looked unpainted.”

I always wondered why the Corgi Bond car was gold.