Media | Articles

J.C. Whitney Lives! Well, Sort Of. But It Definitely Isn’t the Same.

There was no one at J.C. Whitney whose name was actually J.C. Whitney. But there was Winky the Cat, my Most Unforgettable Character from my youthful years of thumbing through Whitney catalogs, when I would have been better served by thumbing through textbooks for a change. It took weeks for me to decide what custom exhaust I should bolt onto my Volkswagen Beetle, which was my first major custom-auto purchase, and during that period I treated the J.C. Whitney catalog with the same somber respect due to, say, The Congressional Record.

The Whitney catalog was available on magazine racks in drug stores, and was cheap enough that any kid could afford it. And why wouldn’t it be? Whitney was perhaps the first marketer who realized that people would actually pay for a publication that was nothing but advertisements. Plus, it couldn’t have been expensive to print, judging from the fact that it was all in crude black and white and printed on paper just one step up from toilet tissue. The people at J.C. Whitney wrote all the copy and laid it out, before it went to the place that also prints—or printed, since they no longer exist—your local phone books.

You could even subscribe to Whitney for free, but it didn’t take long for the company to figure out that you likely weren’t old enough to actually buy anything, and you were back at the drug store paying for it again.

Anybody younger than—what, 40?—is too young to remember the actual catalog, but the name J.C. Whitney still resonates in our jargon, such as, “Man, where did you buy that ridiculous chrome coffee-can tip for your exhaust? J.C. Whitney? Hahaha!” That dig was pretty much interchangeable with “Pep Boys,” though Manny, Moe and Jack have cleaned up their act considerably.

It is difficult to describe to those who weren’t around then how much stuff Whitney sold that you’d never be caught dead with on your car. Ah-ooga horns, an Ocean Liner Blast horn, fuzzy dice, mud flaps, a Continental kit, a Hollywood muffler; this was during a period when your wealthier neighbor might have whitewall tires on his car, a sign of prosperity, so Whitney sold a Whitewall Kit, which contained “pure colloidal white rubber (not a paint)” so you could “make whitewalls out of plain black tires.” It included a brush, a cleaner, and two cans of colloidal white rubber for $2.39.

In later years, Whitney kept up with the times, stocking merchandise that was important to its up-and-coming customers. Such as the fake cellular phone antenna, which stuck to your car’s rear window, signaling to the world that you were connected. Want to take it a step further? It offered fake cellular phones, so at a stoplight, you could act as though you were lining up a date or closing a big deal, for the benefit of those who came to a stop next to you and glanced over.

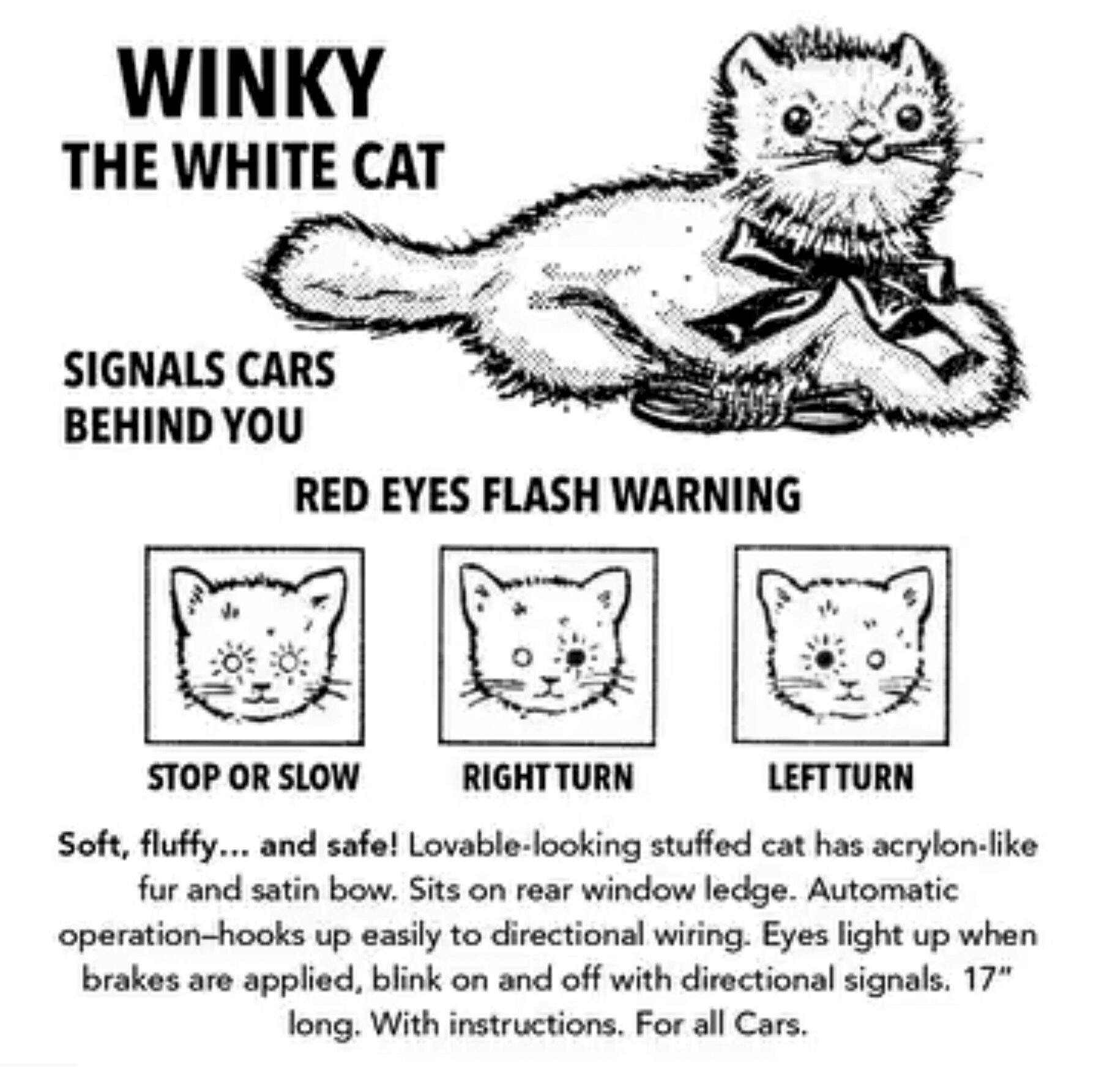

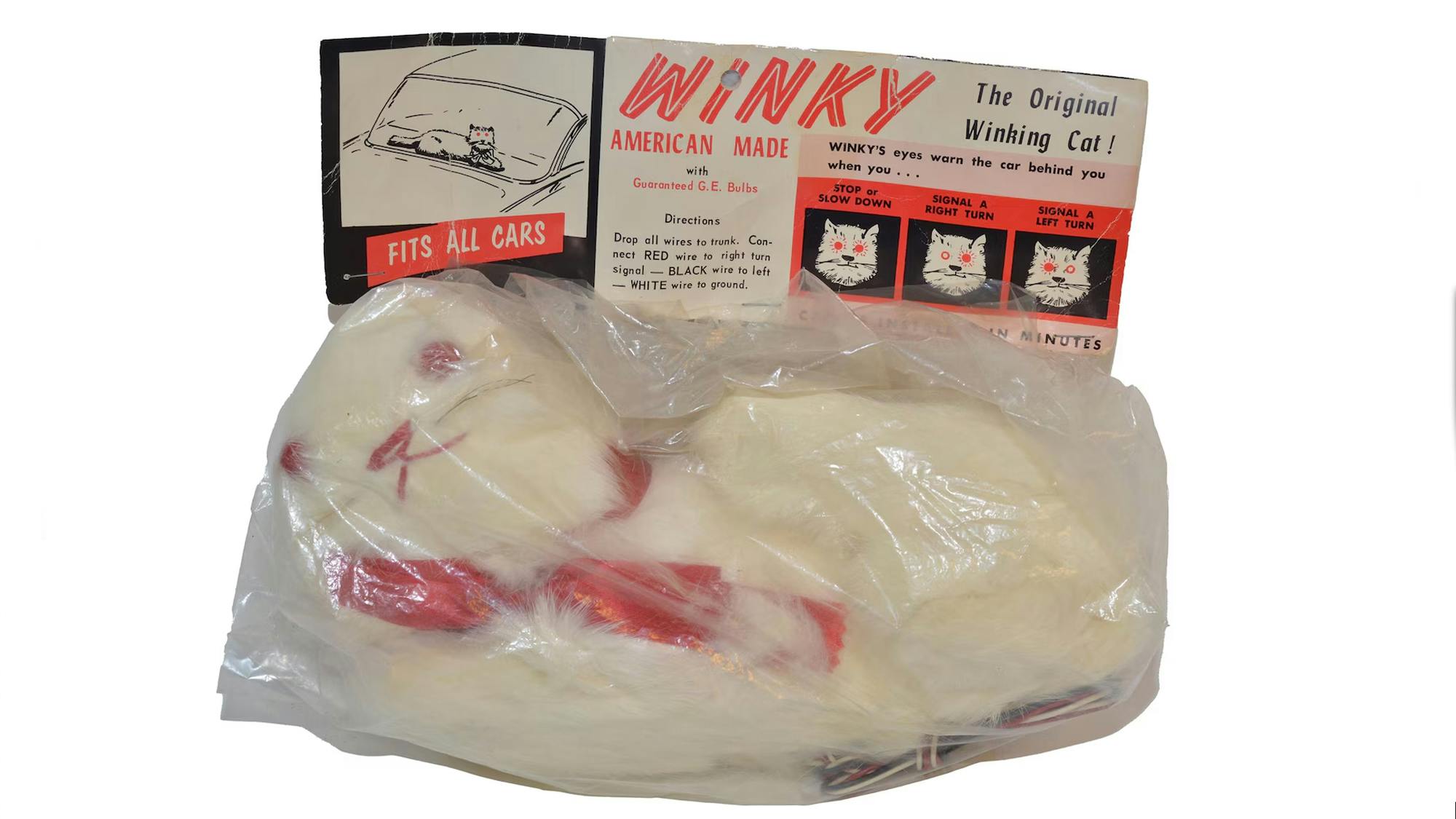

And, through it all, or most of it, at least, there was Winky the Cat (which I always thought would be the name of my band), described here in the catalog: “Lovable-looking stuffed cat has acrylon-like fur and satin bow. Sits on rear window ledge. Automatic operation—hooks up easily to directional wiring. Eyes light up when brakes are applied, blink on and off with directional signals. 17 inches long.” It cost $4.98. Two red replacement bulbs for Winky’s eyes were 69 cents. (There’s an original, creepy-looking, in-the-package Winky on Etsy.com for $595, a markup of $590.02. In 1967, a share of IBM stock sold for $3.14. Today, it would be worth, well, $1,173,000. Okay, so it was a better investment than Winky, but still…)

Winky was, it almost goes without saying, a clever precursor to the Center High-Mounted Stop Lamp, or CHMSL, mandated by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in all new cars sold in the U.S. since 1986. “Winky’s eyes warn the car behind you,” it said on the packaging. “The overall presentation of the entire package is SWEET!,” says the Etsy seller, who offers a variety of cat-centric collectibles.

During my visit to the J.C. Whitney headquarters in Chicago, I asked Gene Geiger, the purchasing manager, about Winky, who had suddenly disappeared from the catalog. The news was not good.

It wasn’t Winky who died, he told me, but his inventor, “an elderly man on the East Coast who would buy the stuffed cats, poke out the eyes, replace them with bulbs and wire them up for 12-volt.” One day, Geiger received a phone call. It was the daughter of Winky’s creator. She informed Geiger of her father’s passing and said she didn’t much want to keep making Winkys. “Toward the end, we were only selling a few thousand Winkys a year anyway,” Geiger said, though that seems like a lot of electrified cats.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The company that became J.C. Whitney was founded in 1915, meaning this year marks its 110th birthday. It was developed on the south side of Chicago by Israel Warshawsky, a Lithuanian immigrant who began salvaging junk cars and selling the parts, typically every nut and bolt. The business was called Warshawsky & Co. Its growth was spurred by World War I, during which Warshawsky injected himself and his firm into the Liberty Bond campaign. At a Chicago fund-raising rally, Army tanks smashed cars supplied by Warshawsky. At a vaudeville theater, Sophie Tucker, an immensely popular singer and comedienne known as the “last of the red-hot mamas,” saluted the recycling initiative with a song called, “I’ve Got a Car That Warshawsky’s Turned Down.”

Not surprisingly, Warshawsky & Co. thrived during the Great Depression, when America’s automotive emphasis was to wring a few more miles out of your current car, and Warshawsky had spare parts for everything. By 1933, Warshawsky began publishing a catalog for its salvaged parts. Covers declared: “The century’s greatest VALUES!” He offered Ford Model A cylinder heads for $3.15.

Only one of Israel’s children had much interest in the family business, and that would be Roy, who had just graduated from the University of Chicago. He went to work at the company, and by 1937 had convinced his father that it would be a good idea to expand the catalog, adding new parts to the salvaged ones that they already advertised. He pushed to have the catalog distributed outside Chicago to create a mail-order demand. Although the company was always known in Chicago as Warshawsky & Co., Roy gave the catalog a different name: J.C. Whitney & Co. “In those days, you needed a less ethnic, Anglo-Saxon name,” said Whitney vice-president John Armstrong when I interviewed him in the 1990s.

But why J.C. Whitney? No one knew—not even Roy’s family. “We can’t get it out of him,” said Carol Warshawsky Steinberg, Roy’s daughter and chairman of the board from 1990 to 2002. There’s some evidence that “J.C.” may stand for “Jesus Christ,” and “Whitney” may be some sort of nickname Roy had in college. But as “Rosebud” was to Citizen Kane, it seems the “J.C. Whitney” name may remain a great unsolved mystery in the auto parts world.

Regardless, Whitney flourished under the strong hand of Roy Warshawsky. He hired Armstrong in 1973 to computerize the company. Shortly after Armstrong arrived, a longtime employee asked him if he’d seen the official Whitney chain-of-command chart. Armstrong said he hadn’t. “So the guy grabbed a piece of paper, drew a box on it, and inside wrote Roy’s name. ‘That’s it,’ he said. And how true that turned out to be—700 people in the company, and they all reported to one man,” said Armstrong.

“That’s the way he ran it. He made all the decisions. He had an endless menu of ideas—eight out of 10 weren’t any good, but the other two were fantastic. And those two kept us going.” Roy hated the media and rarely gave interviews, and when he did, they were short and sweet. He had a penchant for hanging up on reporters.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of the J.C. Whitney catalog back in the day, especially if you lived in a rural area. Despite the fanciful merchandise Whitney offered, there were pages and pages of legitimate replacement and upgrade products, sometimes acquired from top-line manufacturers that would participate in a discounted plain-label program. There were always rumors that at the catalog’s peak, you could build an entire Jeep from mail-order parts.

Automotive writer Jim Donnelly wrote a thoughtful remembrance of Roy Warshawsky for Hemmings a few years ago. Like so many enthusiasts of a certain age, Donnelly recalls J.C. Whitney fondly. “When I was an adolescent,” Donnelly told Hagerty, “there were two days you anticipated eagerly every year: One was when Oscar Koveleski shipped out his Auto World catalog of model kits and slot cars, and the other was the day the thick, pulpy J.C. Whitney catalog landed in the mailbox. Both, though especially J.C. Whitney, were the stuff of days spent dreamily browsing.”

In February 1991, Roy suffered a stroke. The company had been set up so that if Roy became incapacitated, control would pass to his two daughters, Carol and Ilene, and to Roy’s wife, Sarita. The three combined for one stockholder vote, which meant, Armstrong said then, “that they win every decision by a vote of one to zero.”

Carol worked her way up, beginning in the advertising department, writing those little product blurbs. “I remember the first piece of copy I had to write for the catalog,” she told me. “It was for this little scantily-dressed Kewpie-doll air freshener. I thought, ‘What in the world can I say about this?’ From a woman’s point of view, I found it completely offensive. But somehow, I found something to say about it.”

When I visited, Roy’s old office was occupied by the computer that controlled the store’s operation. Efficient and up-to-date, perhaps, but you can bet the computer never had two good ideas out of every 10.

As the online universe blossomed, so did the proliferation of neighborhood auto parts stores, and businesses like J.C. Whitney suffered. In 2002, it was purchased by the Riverside Company, a private equity firm, and the inevitable downsizing began. Eight years later, a company now known as Carparts.com acquired J.C. Whitney, and dovetailed it into Carparts. They did, however, restore the JCWhitney.com site, and started the quarterly JC Whitney magazine, which is actually an odd mashup of magazine and catalog. “Buckle up!” it says on the website. “Flip to the JC Whitney catalog section for exclusive deals on top-notch parts, giving you that nostalgic shopping vibe with a modern twist.”

There’s really nothing nostalgic about it. It’s mostly just a slick packaging of unbylined stories and ads for the Carparts.com inventory, and it’s priced at a healthy $10.99 per issue. I bought it in hopes that it would remind me of the old J.C. Whitney catalog. It didn’t.

“You can’t go home again,” wrote Thomas Wolfe, and truer words were seldom spoken. I spoke to Gary Rovansek, who was president of J.C. Whitney from 1994 to 1998, during his first year in the job, and even then he was sounding the alarm. In his younger days, Rovansek was a Whitney customer, buying custom parts for his 1950 Oldsmobile.

But, he said, kids don’t customize cars today, or even perform much repair work themselves anymore. Today’s cars are too sophisticated. So are the kids. “I have two sons in their twenties, and I never see them working on their cars the way I did,” Rovansek said. Emphasize did, past tense. Rovansek said that he was driving a new Mercedes C-class, “and I can barely figure out where to pour in the windshield-washer fluid.”

“That’s of concern to us because if the average population is aging, then so is our customer base” said John Armstrong, then the company vice-president, when I spoke to him in 1994. “Our customers used to be the guys who were 18, or 20, or 22, and when they went to bed at night—if they didn’t have a girlfriend—they took our catalog. Now, that’s not so much the case.”

So the catalog died, and so did the massive, wood-floored Warshawsky & Co. retail store, where six creaky old buildings were connected and business was carried on seven days a week, serving customers who just wanted a few more miles out of their Impalas and Galaxie 500s, often making repairs where they parked, right there on the street. Near the end, “The store was run like a poor stepchild,” Armstrong said, “but it’s a national landmark, whether the government recognizes it as such or not.”

It didn’t, and it doesn’t. But the memories linger.

“Even if you just gazed at the inventory, you just knew that some of Whitney’s merchandise would make your ride—and you—hipper, cooler and an automotive standout in general,” recalls writer Jim Donnelly. “It was all about being different. Isaac and Roy Warshawsky were undeniable visionaries, and every one of the performance or accessory warehouse stores doing big business today owes these two pioneers a debt of gratitude for inventing their industry.”

Great story! When I was a teenager in the sixties I loved JC Whitney for my hotrods and customs. They had the best glass packs and custom tail lights.

When I got my 1969 Ford Falcon 20 years ago, I had to get a Winky Cat for it like I had in high school vacr in 1973. I searched swap meets and the internet to no avail. So, I went to Toys R US to get a stuffed white cat and then over to Radio Shack to get little red lights. I built my own Winky. When at cruise nights and car shows, the kids love it when I turn on my tun signal. And there is always someone saying I remember that cat.