Media | Articles

Indianapolis Motor Speedway turns 111 years old today

On August 19, 1909, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway held its first race of automobiles, setting the stage for some of the most exciting races in history. What had started out as the vision of Carl G. Fisher had become reality, with a 2.5-mile oval track lined with grandstands seating 12,000, dozens of buildings and garages, several bridges, and an eight-foot-tall perimeter fence. The property glistened thanks to freshly painted white walls outlined with green trim.

In the early days of the automobile, races were held on horse tracks and public roads. Fisher had observed how poorly suited and dangerous these were for racing. In addition, Fisher realized that at such tracks, race spectators were only able to get short glimpses of the racers as they shot down a simple, straight track. An oval track, Fisher believed, would give race viewers a better view and more value for their dollar.

Construction of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway began in March 1909 on 320 acres bought specifically for the purpose, employing 500 workers, 300 mules, and a number of steam-powered machines. The track surface was composed of graded and packed dirt that was covered by two inches of gravel, two inches of limestone covered with a mixture of tar and oil known as “taroid,” then an additional one to two inches of crushed stone chips that were also soaked with taroid. To top it all off, a finishing layer of crushed stone was added. The work was completed at a cost of $3 million ($85 million in 2020).

Initially the track was intended to function as a shared proving ground for what was becoming a thriving automotive industry in and around Indianapolis. By 1908, the town ranked fourth in the country in terms of automobiles built. By 1913, Indianapolis was second, right behind Detroit. Along with private testing, Fisher and his fellow investors believed the Speedway would be an excellent venue for automobile-racing events. There, the public could witness the competition of the racing versions of the autos then for sale in showrooms.

At first, Fisher had planned for the track to be a five-mile oval, but he later revised the design to consist of a rectangular-shaped, three-mile oval with a two-mile road course inside of it. When connected together, they would create a five-mile course. P.T. Andrews, the civil engineer in charge of the project, pointed out that a three-mile outer oval would be possible on the allotted acreage. However, that would place the straightaways so close to the edges of the property that there would not be sufficient room for the grandstands. Instead, Andrews proposed an outer oval of 2.5 miles; the road course was omitted soon after work began. The final track’s configuration is much the same as it is today: a 2.5-mile oval with four corners banked at nine degrees, 12 minutes. The 50-foot wide front and back straightaways are five-eighths of a mile each, and the four turns are 60 feet wide and a quarter-mile long. The turns are connected at the north and south ends of the track by one-eighth-mile straights—the “short chutes.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A hot-air balloon race held on June 5, 1909, was the first public event held at the Speedway. The first motorized-vehicle event was a motorcycle race that ran on August 14, 1909. Originally scheduled as a program of 15 races held over a two-day span, the event was cut short after just one day. Jake DeRosier, riding an Indian motorcycle, was severely injured when the bike’s front tire exploded after being pierced by the track’s sharp stones.

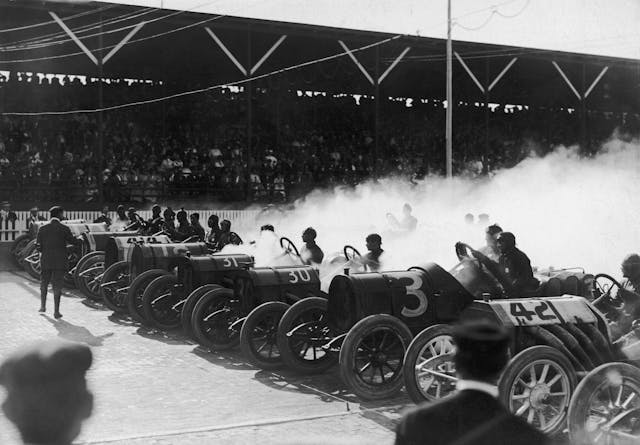

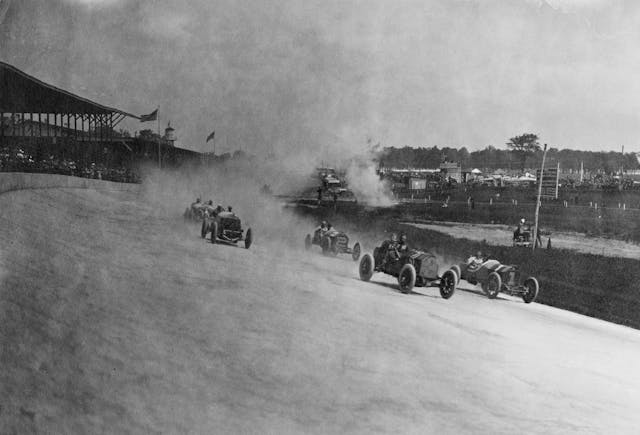

The first automobile race was held five days later, on August 19, with a total of 15 manufacturers showing up for practice. Once again, the surface of the track was an issue, with drivers being sprayed by the dirt, oil, and tar that was kicked up by the drivers ahead of them. As practice progressed, ruts and potholes began to appear in the turns. Speedway workers were hurriedly dispatched to oil and roll the track surface before the gates were opened.

Somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 spectators attended, paying as much as one dollar for a ticket. The third race of the day, a five-miler, was won by Wilfred “Billy” Bourque. On Lap 58 of the main Prest-O-Lite Trophy Race, a 100-lap event, the leader—Swiss-born Louis Chevrolet, piloting a Buick—was temporarily blinded by a stone that shattered his racing goggles, causing Chevrolet to exit the race. On that same lap, Bourque’s Knox race car crashed, flipping end over end on the front stretch and smashing into a fence post. Some witnesses claimed the cause of the crash was a rear-axle failure; other witnesses said the crash occurred when Bourque’s riding mechanic, Harry Holcomb, warned Bourque that another car was gaining on them. With Bourque turning to look back, the car swerved, hit a rut and crashed, making him the first driver to die racing at Indy.

That first day of racing at the Speedway yielded four finishes as well as two land-speed records. Worries about the safety of the track, though, caused officials to consider canceling the remaining two days of racing. Fisher vowed that he could repair the track by the next day and persuaded the officials that the races could go on as planned. Twenty-thousand spectators attended the second day of racing; there were no major accidents, and additional speed records were broken.

On day three of the racing, 35,000 spectators attended the grand-finale, 300-mile race. At the 175-mile point of the race, the right-front tire of Charlie Merz’s National blew, sending him through five fence posts of the track’s outer fence and into a group of spectators. Merz avoided injury, but his riding mechanic, Claude Kellum, and two spectators were killed; several more suffered minor injuries. Just ten laps later, Bruce Keen struck a pothole that sent his car into a bridge support. The race was halted, and the remaining drivers were presented with engraved certificates instead of trophies. As a result of the race, AAA boycotted any future races at the Speedway until significant improvements were made. It was an inauspicious beginning for the track.

Fisher and his partners started exploring the viability of using bricks or concrete to pave the track. Since methods of paving in 1909 were still relatively unknown, with only a few miles of paved public roads existing in the entire country, there was little knowledge of what method would work best. Bricks were subjected to traction tests, proving that they could endure the abusive environment of racing.

Less than a month after the first car races had been held at the Speedway, the repaving project began. Five Indiana manufacturers supplied 3.2 million bricks, each weighing ten pounds, to the track. Each brick was laid by hand over a two-inch-deep cushion of sand, then leveled, and the gaps filled with mortar. At the same time, a 33-inch-tall wall of concrete was constructed in front of the main grandstand and around all four corners to protect spectators. The final brick that was added to the track was made of gold and was laid in a special ceremony by Thomas R. Marshal, the governor of Indiana. Before the work was completed, locals had already nicknamed the track “The Brickyard.”

Asphalt gradually was added to various sections of the brick surface; patches were added to rougher sections of the turns in 1936 and all turns were completely paved with asphalt in 1937. In 1938, the entire track was paved with asphalt except for the middle portion of the front straightaway. Today, three feet of the original bricks remain exposed at the start-finish line.

Celebrating its 111th birthday, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing,” is today the oldest continuously operated race track in the United States. It is the third-oldest permanent automobile racetrack in the world, behind Brooklands in England and the Milwaukee Mile in Wisconsin. It was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987 and is the only site to be associated with automotive racing history. And with a seating capacity of 257,325, it is the highest-capacity sports venue in the world and hosts the largest single-day sporting event in the world, the Indianapolis 500. Not even a visionary such as Carl G. Fisher could have imagined such success, and it is a tribute to his persistence and dedication that Indy is the shrine to motorsports that it is today.