Media | Articles

In the Moment: NASCAR fights, BMWs, and a Chevy Nova

Welcome to a regular feature we call In the Moment!

Several months ago, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our staff chat room.

In addition to being a lifelong student of automotive history, Smith drinks a lot of coffee. Each of those photos was accompanied by a caffeine-fueled explanation. We liked these drops a lot, so we started sharing them here on Thursdays. Then Sam started writing them specifically for publication, which is where we are now.

Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

We were talking about something else, when Cam threw in the Nova.

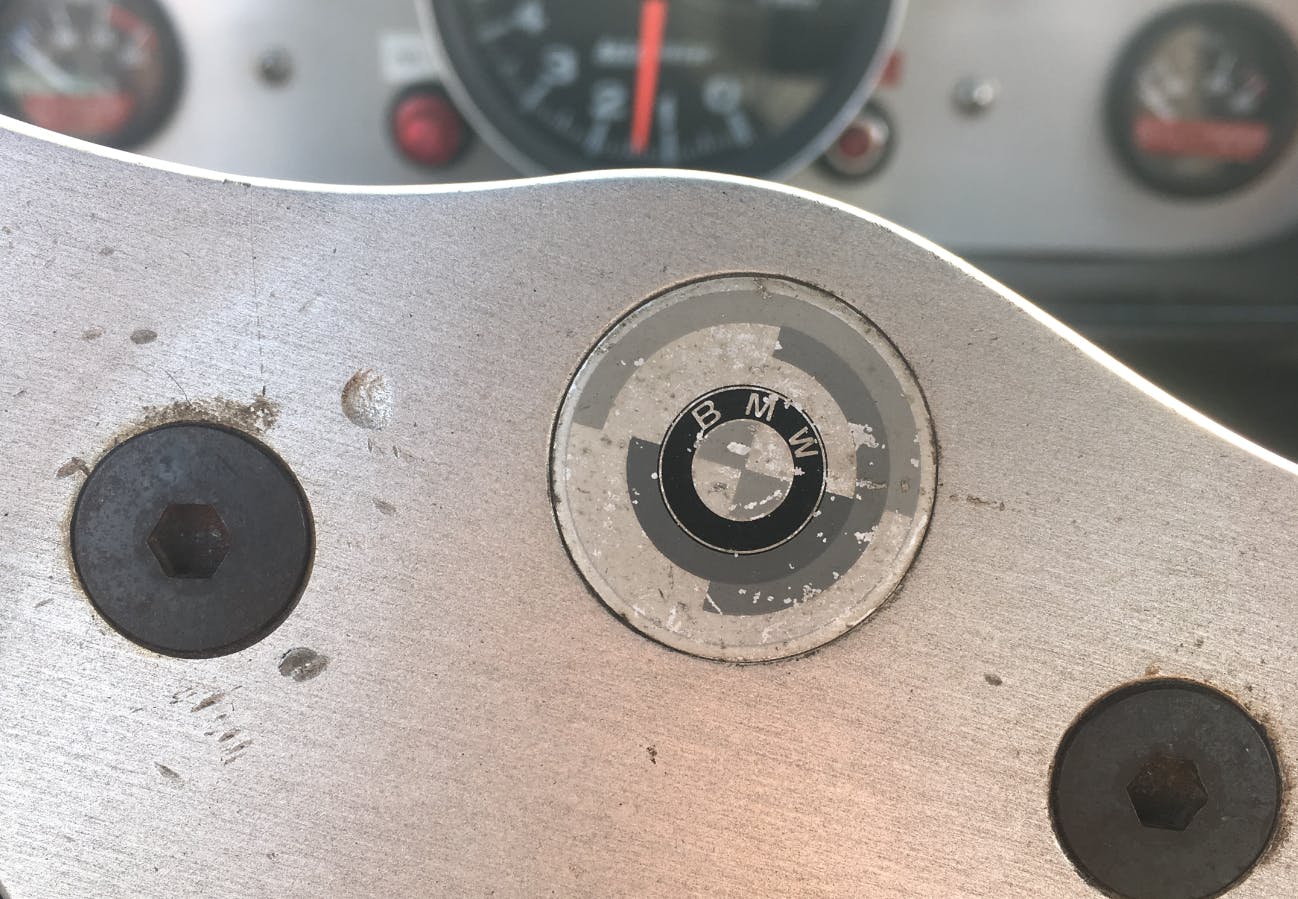

The striped hunk of elegance at the top of this post is a 1975 3.0 CSL IMSA Group 4 race car. It weighs around 2400 pounds and carries, under that long and graceful hood, a twin-cam straight-six of more than 430 hp.

We’ll get to all that in a minute. First, we must discuss a screencap.

This image below is a screenshot from one of Hagerty’s in-house Slack channels—a chat room for the whole digital edit staff. Cam Neveu, an editor, has just pasted in a Getty wire shot from the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona.

The car in that shot, an IMSA Chevy Nova, is being driven by contemporary NASCAR driver Donnie Allison.

Chat room with many staffers; everyone is doing a business; in pops some random archive image; people take a minute to gawp and make noise; work carries on moments later. This happens a lot around here.

Side note: I work with a good group of folks.

Side note to a side note: Donnie Allison! What a dude. Three years after that Nova shot, he co-starred in one of the most significant moments in NASCAR history. A quick round of punchy-slappy-footsie, plus some literal mud wrestling, immediately after the 1979 Daytona 500.

On the last lap of that race, Donnie crashed Cale Yarborough. Or Cale crashed Donnie? There is tape, but nobody agrees. Or maybe, knowing NASCAR, they’ve agreed to pretend to not agree. Later, Yarborough found Bobby Allison, Donnie’s brother. Being a sensitive man, Cale chose to hit Bobby in the face with his helmet. He drew blood. The two went to town. Donnie came along and tried to pull them apart.

The whole thing was broadcast live on national television. NASCAR’s audience exploded. Darrell Waltrip called it “a storybook day.” Donnie said the event changed NASCAR’s complexion. “People realized . . . after that wreck and that brawl, that we were as serious as those other sports.”

Yarborough, for his part, just called it “great racing, great fighting, and a great time.”

Heck, mes amis, it’s only ol’ Cale.

(Side note to a side note to a side note: That link takes you to one of my all-time favorite pieces of automotive journalism. Bob Ottum for Sports Illustrated in 1981. Yarborough took a Camaro to Le Mans and Ottum went with. Click only if you love stories of Southern men using V-8s to make the French uncomfortable.)

Back on topic: Fat-tired IMSA cars! They give much grin. So Cam put the Nova into the chat, and then I saw that Nova, and I and thought, Hell, Donnie Allison. The Alabama NASCAR legend. Remember how his shop met that IMSA car you love, Smith?

Many IMSA machines of that era are special. I love one more than most. A machine I have somehow been lucky enough to test. One that passed through the Allisons’ shop.

One that traveled a very long way to get there.

In the early 1970s, BMW was small. The company had been founded in 1916 as a manufacturer of aircraft engines. There was much early success, and then, in World War II, much loss. By 1959, the marque’s financials had grown so dire that arch-rival Mercedes-Benz came inches from a takeover. A mere decade later, BMW had recovered greatly but remained under strain. European racing was done on the cheap, almost entirely handed off to factory-backed tuners like Schnitzer and Alpina.

The United States was different. The brand’s American distributorship had long been handled by New York foreign-car impresario Max Hoffman. In 1975, seeking more control in its largest market, BMW ended its arrangement with Hoffman. A wholly owned offshoot, BMW of North America, was created and based in New Jersey.

Where the German home office had little money, the American outpost had even less.

That badge was so unknown here! Even in 1975, when a 3.0 CSL won the 12 Hours of Sebring. Even in ’76, when another CSL won the 24 Hours of Daytona. By the latter year, BMW’s beloved “02″ sport sedans had been in production for a decade. Those cars had essentially built the brand’s early American reputation from nothing, but the name was still far from household.

English cars had played a massive role in the launch and growth of America’s postwar sports-car market. Many people here saw those letters and simply connected dots:

“British Motor Works, eh? Where in England?”

The Germans were not thrilled about this. They also thought racing the most cost-effective way to build a brand. Drivers were hired and competition cars prepped. They sent people to America, to run with IMSA, the International Motor Sports Association.

The handful of German mechanics shipped stateside met barriers of language and culture. The cars had issues of their own. Early results were embarrassing. And yet eventually, through a quirk of fate, the team ended up based in Alabama. In the city of Hueytown, near Birmingham, at the shop of Bobby and Donnie Allison.

The Allisons were the core of a group of NASCAR drivers known as the Alabama Gang. After a while, a few folks began to call the German mechanics by the same name. And so a handful of Teutonic dudes with wrenches and suitcases worked among Southern racing royalty, with guys known for making tough race cars, and the CSLs slowly became more durable and stiffer in structure, and most of all, they grew faster.

An underfunded factory team, in the world’s largest car market, road-racing at the highest level, for the first time! From a NASCAR shop, at a time when NASCAR didn’t know squat about turning right! It sounds insane.

History books often paper over the CSL’s flaws. The name meant 3.0 liters, Coupe Sport Light. In road trim, that model was a hot-rodded version of BMW’s 3.0 CS, a long-legged, blast-to-Paris-at-midnight masterpiece that was itself an evolution of the 2.8-liter BMW 2800 CS. Which was, in turn, a six-cylinder update of an earlier, four-cylinder model, the 2000 CS.

Internally, BMW called this chassis E9. Although heartbreakingly pretty, the car’s body had been designed for relatively tame work. The basic structure, built by Karmann, was remarkably flexible. It wore no B-pillar whatsoever and only toothpick-thin A- and C-pillars.

In IMSA, even with a host of tweaks, the cars were down on grip and durability. They had strong power, though, when the engines stayed together. Plus a certain joie de vivre.

“They were really designed for [German factory driver] Hans Stuck,” Sam Posey once told me. Just a couch, he said, soft and particular. You had to “drive through the side window,” he added—drive sideways—to make the car work.

Slides are rarely the fastest way around a corner. Once, however, when tire and chassis technology were different, you could get away with that sort of thing and still go pretty quick. More to the point, for a certain sort of person, it is bonkers fun.

Posey is a lovely man, a former ABC Sports commentator who found fame driving sports and Trans-Am cars. He drove factory CSLs in America and at Le Mans but never fell in love with the model. Not that others didn’t. There was Stuck, of course—a touring-car legend whose resume now includes 74 Formula 1 starts, a DTM championship, and two overall wins at Le Mans. The immensely talented Brian Redman. And me, just some club-racer journalist dork.

Everyone loves an underdog story. Relevant notions I also love:

- A good race car driven clean and fastAnd:

- A sideways anything

That moment in fourth gear, you know, where you might as well be on snow. Thinking about momentum and balance, blisteringly awake, planning a lot and reacting a little.

It’s like ice skating, except sometimes, your right foot is gunning a fat straight-six with six throttles and two cams, and the whole thing goes, as we say in the business, Honk.

In 1975 and 1976, BMW of North America ran five CSL tubs in IMSA, in the Camel GT series. In 2017, I had a chance to drive one of the five, chassis 2275985, at the Rolex Monterey Reunion. The Laguna Seca vintage-race weekend formerly known as the Monterey Historics, held in Northern California every August.

The Reunion is a high-profile American vintage race. Which is to say, both a race and not. Several years ago, I heard someone call the weekend, “a really fast car show where some racing occasionally breaks out.” Some people show up and drive at the limit; far more run only as hard as they know how, which is not always the same thing.

Would it be nice if all historic racing were razor-sharp, as close and fast as it gets? Sure. But we can’t all be the Goodwood Revival, right?

The CSL I drove has been owned by BMW of North America since new. It is regularly demonstrated by guests and executives. In ’17, I was at the wheel for the British magazine CAR, part of a cover story on BMW’s then-new 8-series coupe. A pinch-me moment, rare even by the standards of this strange and wonderful job. An elegant and romantic machine of great importance and history, built for and happiest at max hoot, and someone said, Here, boyo, go hoot.

If my life has anything like a story, that tale is peppered with irrational attachments to cars from these people. So much time poured into so many projects, none of it justifiable by anything other than emotion.

One night, shortly after that Laguna drive, I sat down with a beer and some cockpit footage. I edited up a quick little video for friends. That video wasn’t aimed at public consumption, but I left it public anyway. A few thousand folks found it.

There are slides, but I am not a pro and my driving is not the point. From a GoPro taped to my helmet, there is sound.

That engine!

The block geometry behind that noise was laid out in the 1960s. It lasted until the 1990s, helping build a company. Missteps came before that engine and have come since, but the high points are almost painfully high.

No CSL is perfect. The best cars from Munich have always been compromises. Like any good sport sedan, the great BMWs have been engaging and deeply practical road machines first. Hung on the word “sedan.” The “sport” bit is still a priority, just second in line.

People gripe about the flaws. The understeer, the repair bills and short maintenance intervals, the kinematic failings, and so on. To obsess over that stuff is to think the cars purebred, designed for one purpose, which they are not. Apples to apples, model year to model year, a Porsche of equivalent focus and power-to-weight is usually a little more satisfying, a little more fit for track use, more balanced and evocative.

Still, some of us have a soft spot for certain compromises. For a carmaker that is still owned by the family that saved it from Mercedes. Even if the folks currently at the helm don’t always seem to know what they’re doing, or quite what their cars should be in the modern world.

Alabama! The Allisons! Such a funny little part of that history. And a reminder that we are all perpetually on the way to somewhere else.

As a hero of mine, another racing driver, once said, “Change is the only constant. Hanging on is the only sin.”

Except, of course, when it comes to love. I am a sucker for it.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Watching that video brought some serious flashbacks to that RUF CTR Yellow Bird hero run at the Nurburgring… much props.

Since the vast majority of us won’t ever get the opportunity to drive a one-of-five IMSA special, thank you for allowing us to live vicariously through you. I for one will never tire of the rambling diatribes nor the hair-raising video clips.

Good job, Kevin. You speak for me, especially the vicarious part. What wonderful sounds and images!!

I’ve always loved Sam’s writing, but now I have the same appreciation for his driving talent.

Throw it into the corner, sort of catch it straight, then hammer it. You are very good at that. Looks like a blast!!

Omg What an awesome Workout !!

Still looking for the aforementioned Nova…

I lived in Jacksonville, FL and Bob Snodgrass was a friend so I remember when Peter Gregg, of Porsche fame, campaigned two of these cars in IMSA. I think this lasted just one year and he got rid of them. Your article explains why. BTW, I have a 2006 330Ci ZHP, bought new, which I have built into a M3 (without the flares) because the BMW club people told me that the M3 motor was a problem but the ZHP motor could be supercharged which I did when I fixed all the other factory defects (among them the subframe). This has been my daily driver ever since and I still smile every time I drive it.

I saw those CSL’s race at Road America in the mid 70’s and they were stunning to watch in action. Along with the other cars of that period

That’s a fun drive.

Sam: I have enjoyed your writing ever since your monthly column (likely for small pay!) in the Roundel. Your contributions on Hagerty are always entertaining. You have a nice style. I love cars but have never been a big race fan. I’d rather drive than watch someone else do it.

However, I was intrigued by your reference to the 1981 Bob Ottum SI article on Cale Yarbrough at Le Mans. It was just as good as you suggested! Great stuff. Would never have encountered it without your mention. Keep writing and keep driving!

Another fine ITM article that seems to be a scattershot stream of semi-consciousness but is something else entirely.

A sidenote (if you will): Bob Ottum’s article is another fine bit of writing and perhaps something more. Where he wrote that Cale’s engine created “a sensation of silver fillings dropping out of teeth”, you once wrote of the sound of an engine “so fecund that women two counties away became pregnant.”

Another sidenote. You literally had your hands full in the video at Laguna Seca. The contrasting initial voiceover with its soothing music and Fred Rogers voice was a perfect segue to tarck audio.

I now have a new definition of “Neutral Handling Race Car”: equal parts oversteer and understeer. 😹🤦🏻♂️😬