Media | Articles

In the Moment: A dictator and a V-16

Welcome to a new weekly feature we’re calling In the Moment!

This all started in Slack, the messaging software we use for staff communication. Several weeks ago, Hagerty’s editor-at-large, Sam Smith, began kicking off our mornings by plopping a random archive photo into our chat room.

In addition to being a lifelong student of automotive history, Smith drinks a lot of coffee. Each photo he dropped into the conversation was accompanied by a bit of caffeine-fueled explanation.

We liked these drops a lot, so we’re sharing one here each Thursday. Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments! —Ed.

**

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Picture Germany in 1934. A certain person is attempting to wrap the European continent around his warped definition of order. There are storms on the horizon, and yet, there are also ways to unplug.

You can step out of reality for a moment, watch a group of gladiators drive fast cars in circles. If you are lucky, you can see those individuals compete in a place that demands much of them.

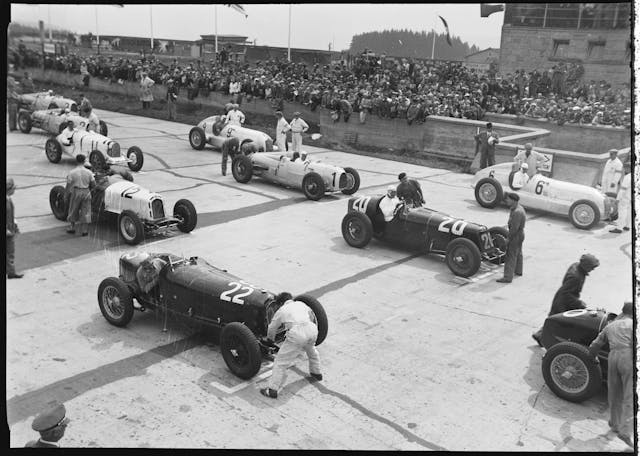

Look at this row of machines. This is the starting grid for the 1934 German Grand Prix, at the original, 14-mile Nürburgring. Grand Prix racing was the precursor to Formula 1. Its roots lie in turn-of-the-century French “grand prize” road contests. The sport gained its current name in 1950, but the “G.P.” phrase has always been used to denote a significant event.

The crowd is thick. Most of the cars have hand cranks at the front, for starting the engine. The mechanics wear coveralls and flat caps. A few wear berets! Perhaps they are French?

Then as now, the world’s most prestigious motorsport was hung on the differences between nations. There were international racing colors. Thank a man named Elliott Zborowski, the father of Louis “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” Zborowski, who suggested them.

French cars were generally painted blue, bleu de France. British ones were green. Italian cars were red, similar to the rosso corsa of modern Ferraris, except when they weren’t. (Factory Alfa Romeos from the marque’s between-the-wars golden age were essentially maroon.) Finally, German cars were white.

These colors were found in international road racing for decades. Teams made alterations and nobody seemed to mind. The American shade, for example, was once red. Then, in an era when virtually no American cars raced in Europe, it became white with a blue stripe. It later shifted to a darker blue with white striping. (Think Shelby 427 Cobra S/C or the earliest Corvette Grand Sports.)

Back to 1934. The image at the top of this page was taken by a renowned Hungarian photographer named Zoltán Glass. Most of the cars look similar. And then, in the middle, is an outlier.

Glass, a photojournalist, lived in Berlin. He loved motorsport and spent a great deal of his free time covering races at the Ring. Again, this was the old circuit, the Nordschliefe, the 14-mile North Loop. Constructed from 1925 to 1927, it was then and remains the largest purpose-built motorsport venue on the planet.

Imagine: A purpose-built road through German mountains, used almost exclusively for racing. Pavement bordered only by hedges. A place where you could go faster, and hold those speeds for longer, than at any other paved surface on earth.

People died, of course. Regularly. They were hucked into the bushes like rag dolls, tossed from cars intentionally built without safety harnesses, because everyone believed it was safest to be thrown clear. If you were going to design a machine to kill racing drivers, in the era before cars were designed to protect a human body, it would probably look an awful lot like the track around Castle Nürburg.

Such a different world, then, for so many reasons.

Zoltán Glass took that photograph, plus the alternate view seen here, just four years before fleeing Germany. In 1934, he was working for the German newspaper Berliner Tageblatt. In 1936, he was dismissed from that paper for having Jewish ancestry. In 1938, like so many others that year, Glass left Germany for London, negatives packed, fearing for his life.

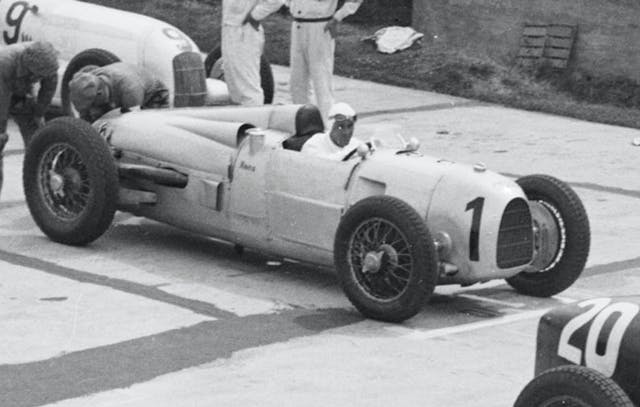

Again, note how that car in the middle looks different. It is connected to why Glass left.

Look at the other machines. All are long in hood, engine up front and driver behind. Only two other cars—numbers 2 and 3, at upper left—look like number 1. They are from the same team, Auto Union. Auto Union was formed by the merging of four carmakers: Audi, DKW, Horch, and Wanderer. (The modern-day Audi marque is Auto Union’s descendant and uses a version of its logo; the four rings represent those four companies.)

Look at the men in the cockpits, bodies half out in the breeze! Only a few wear hard crash helmets. Most are in cloth caps. The machines with slots around their front grilles are Alfa Romeos. The horseshoe-shaped radiator at the back is attached to a Bugatti. Car number 6, tall and chunky, is a Mercedes-Benz.

Just a few seasons prior, Alfa had dominated grand-prix racing. Its cars were simple and strong and built around virtually unburstable engines. The Bugattis were also once dominant. In 1933, however, the rules shifted. G.P. cars had been required to weigh 1984 pounds (900 kg) minimum; they were now limited to a 1653-pound (750-kg) maximum, absent tires, fuel, or driver. Adolf Hitler’s German Ministry of Transport offered 500,000 Reichsmarks to German manufacturers in order to fund racing development. This money was initially claimed by Mercedes. Then Auto Union reps met with Hitler, and the funds were shared between the two companies.

The point, of course, was to demonstrate German engineering might as superior. As the government thinking went, this was because Germany was superior, because German men were superior. That last belief was tied to how Hitler was an inhuman dictator who literally started a global war and, in a separate horrible act, commissioned a system to murder millions of innocent civilians in cold blood.

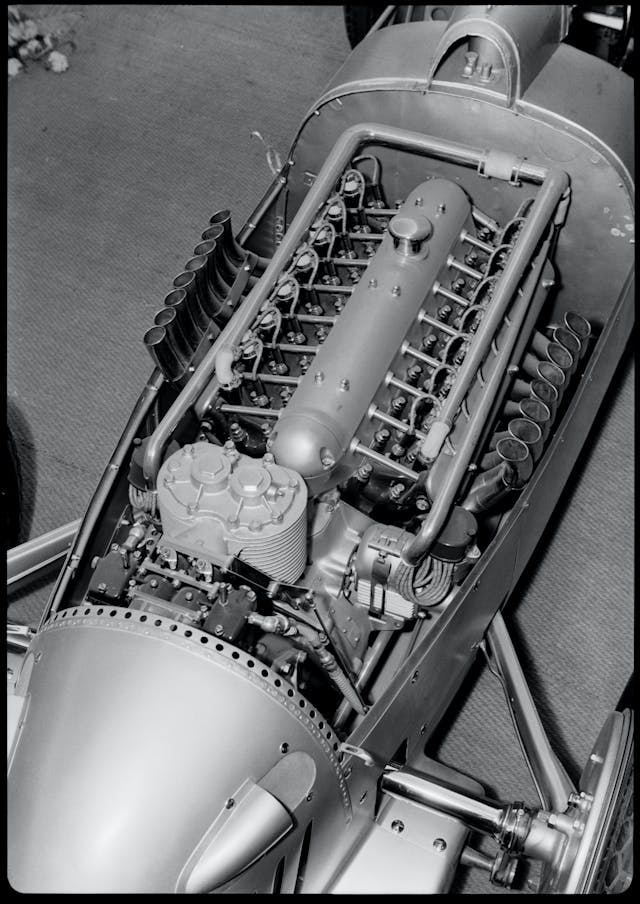

Five hundred thousand marks was not world-changing money. As Hagerty’s own Don Sherman points out, in modern dollars, that figure is only about $2.4 million. (Your average modern F1 team has a budget in the hundreds of millions.) Still, that funding was enough to ensure that Mercedes and Auto Union came to dominate European motorsport. The technology developed by the two companies was immensely advanced, but it took time to sort. The Auto Unions, for example, ran a supercharged V-16 installed behind the driver, an engine designed by the one and only Ferdinand Porsche. This cannon of an engine was initially just 4.3 liters in size. In 1934, running 9 psi of boost, it made 295 hp at 4500 rpm.

By 1937, that same engine design, punched to 6.0 liters, was making 520 hp at 5000 rpm. More important, it produced 630 lb-ft of torque at 2500.

Six hundred and thirty pound-feet.

Through wire wheels.

Racing surfaces of the era were generally rough and unpredictable. Porsche’s thinking—which proved right—favored low-rpm torque for such conditions, as it would be easier to control. Audi later used a virtually identical V-16 for record-breaking. That engine was installed in a streamliner and run on a closed autobahn at 242 mph. Later versions would see nearly 270.

Mercedes also built neat engines during this period; Auto Union merely led the way. The development process remains utterly fascinating. The two carmakers struggled with fuel quality, unable to find a commercially available cocktail that would work. Each eventually brewed their own fuel, toxic stuff that was essentially the bad parts of Newark blended with liquid cancer. Tires were uncharted territory; the torque on hand would literally shred them in a handful of laps. No one had ever tried to put that much power onto pavement for that long.

Most of all, they could not find enough talent. A handful of drivers possessed the skill to drive such cars quickly. Only a few of those people could really run them.

Look at the Alfas on that grid. Good for 160 mph, maybe, in the right conditions. The Auto Unions could do 180.

Early on, the German cars were painted white, that national color. They were later silver or bare metal. If you believe the legend—and most people do not—this was because the paint weighed too much.

One of the oldest questions in the world concerns whether we can or should separate a work from its creator. In this case, the lines are more clear. That utterly reprehensible human did not create Dr. Porsche’s work. He funded it, hoping the result unstoppable. It wasn’t, but nothing is. At the 1935 German Grand Prix, just one year after this photo was taken, a charismatic little Italian man in an underpowered Alfa Romeo took on the Germans on their home turf and won.

His name was Tazio Nuvolari. One of the greatest drivers in history. He persisted that day through sheer will and spit and art—the stuff everyone loves about Italians. At the checker, Nazi officials frowned in disgust.

I adore 1930s racing cars. They come from a romantic moment when the automobile was old enough to be legitimately fast but young enough to still reflect, for the better, our differences.

I’ll leave you with my favorite Nuvolari quote. It is unrelated to most of this but always makes me smile.

Someone once asked the man if racing frightened him.

“Tell me,” he replied, “Do you think you’ll die in your bed?

Have a good day, guys!

—Sam

A number of years back, I became aware of the Auto Union – Mercedes rivalry of the 1930s and spent some time studying the era. In that process, I came across the name Zoltán Glass, and found a book called Speed and Spirit. It was published in 2000 by the Mercedes-Benz Museum and features his photography. Well worth searching for if you’re interested in that period of history.