Media | Articles

Sweeping Le Mans in ’66? Just one of Shelby American’s miracles

John Morton parks in front of a broad red-brick building that is one of the last vestiges of what had been a blue-collar Venice neighborhood in the early 1960s.

Across the street, condos now occupy what was then a vacant lot. A block away, modest starter homes have undergone million-dollar renovations. The coffee shop where Morton often ate dinner is now a hot-yoga studio. But the nondescript building looks virtually unchanged.

“That’s where the receptionist sat. I used to sweep those stairs,” Morton tells me as we peer through a window. “Shelby’s office was up here,” he says, nodding at a second-story stucco overhang. We walk over to a roll-up door. “All the cars came in and out through this. There was a kind of hallway that led to a big, open main area. When I started, the Scarab Formula 1 car was still there. Sometimes, I’d sit in it when I ate lunch.”

Today, the building has been remodeled and subdivided into recording studios. Six decades ago, it was the beating heart of Shelby American, the company that Carroll Shelby formed to build the Cobras that later served as the foundation of his racing empire. Even today, 1042 Princeton Drive is hallowed ground for fans of Shelby’s iconic creations.

Morton started working here in 1962, when he was 20 years old, first as a janitor, then as a parts chaser, next as a fabricator, and finally as a race car driver. When he arrived, Shelby had a dozen guys working for him, and the Cobra hadn’t yet competed in its first race. By the time Morton left in 1965, the company was the biggest, baddest, most successful motorsports-cum-high-performance operation in the country and second in the world only to Ferrari.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Even fair-weather car guys can tick off most of Shelby’s greatest hits, but they don’t realize how fast Shelby American came together or how quickly it fell apart—six measly years to create a legacy that has lasted six decades. Over time, the operation expanded to fill a pair of aircraft hangars at Los Angeles International Airport. But most of the projects were developed simultaneously in the cramped, noisy, 10,860-square-foot shop on Princeton Drive. Working flat out, fabricators and mechanics moved so quickly from one soon-to-become-legendary car to another that they didn’t realize they were making history.

Consider the cars Morton would have seen parked cheek to jowl when he reported to work one morning in December 1964: the Ford GTs that would eventually sweep Le Mans; Daytona Coupes being prepped to win the GT world championship; the King Cobras that had just starred in the precursor to the Can-Am series; 289 competition Cobras destined for privateers; the big-block roadster that would ultimately take shape as the 427 S/C; the first of the Mustangs being transformed into the GT350; even a prototype Sunbeam Tiger housed in a “secret” room.

“It was a magical space,” former Shelby American photographer Dave Friedman says. “We created miracles there.”

This is how miracles happened.

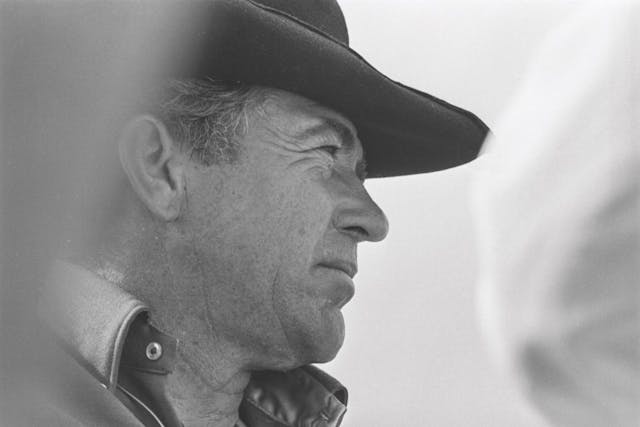

Carroll Shelby. Has the racing world ever produced a more colorful, captivating, and complicated character? Handsome as a Western movie hero and charismatic as a royal courtier, he was the son of a rural mail carrier who never lost his East Texas drawl, even after graduating to Lacoste polo shirts and Gucci loafers. Women wanted to bed him. Men wanted to be him. Investors, meanwhile, often wanted their money back. Only half-jokingly did friends liken him to Billie Sol Estes, the smooth-talking Texas con man infamously convicted of fraud.

Shelby has passed so thoroughly into legend that it’s hard to appreciate the implausibility of his metamorphosis from out-of-work race car driver to captain of industry. During his prime as a racer, motorsports was a largely amateur proposition, and most of his earnings came from under-the-table payments from rich patrons. His biggest claim to fame was that he’d won the 24 Hours of Le Mans—wearing overalls, like the chicken farmer he’d once been. But Ron Flockhart, Ivor Bueb, and Ninian Sanderson also won at Le Mans, and none of them were household names.

Angina, a chronic shortage of blood to the heart that feels like a vise squeezing your chest, forced him to retire from racing in 1960. Shelby was nearly broke. He migrated to Southern California, rented a tiny office in Dean Moon’s humble shop in Santa Fe Springs, and struggled to keep his head above water through a combination of side hustles, including a high-performance driving school, a Goodyear tire distributorship—even a gig as a magazine editor. He’d been dreaming of building a sports car with an American V-8 since 1951, when a project he’d started in Dallas foundered because, he once told me, “We were making so damn much noise that my wife ran us out of the garage.”

The annals of automotive history are littered with dreamers who tried but failed to put their own high-performance machines into production. Shelby made it happen by practicing a form of alchemy, creating something out of nothing. He’d heard that the owners of AC Cars were looking for engines to drop into their handsome British roadsters. He also knew that Ford Motor Company was ramping up production of a brand-new V-8. So Shelby told AC that he had a supply of motors, and he told Ford he had a supply of chassis.

“Christ, the way Carroll talked, you would’ve thought he was a damn millionaire,” Ford executive Homer Perry said many years later. “We gave him a couple of engines, and [Ford Division assistant general manager Don] Frey and [Ford NASCAR chief Dave] Evans and I were shocked to find out later that he was broke. We never really expected to see him again because he didn’t have any money.”

In January 1962, a massive wood crate was delivered to the AC factory in Thames Ditton. Nobody knew what to make of the weird legend stamped on it: FOMOCO. Only when mechanics opened it did they realize it contained a Ford V-8. At the end of the month, after the engine had been installed, Shelby tested the car at Silverstone, then flew straight to Dearborn. A week later, he signed a contract with Ford. Shelby would get engines, transmissions, and other parts in return for a “Powered by Ford” plaque on the fenders of his ambitious Anglo-American sports cars.

In February, AC shipped a chassis to Los Angeles. Shelby picked it up with a borrowed trailer and dragged it back to Moon’s speed shop. It took a day to install the Ford running gear. That night, with the body in bare, Brillo-polished aluminum, Shelby laid rubber down on the streets of Santa Fe Springs. He later claimed that the name of the car had come to him in a dream. When he woke up, he’d written it down on a notepad next to his bed: Cobra.

The Cobra

Shelby was a promotional genius; even before he showed the car to the public, he put it in the hands of car magazine editors, who rewarded his largesse with reams of free publicity. It wasn’t until April 1962 that the first—and, at that point, only—Cobra debuted at the New York auto show, painted screaming yellow by gonzo customizer Dean Jeffries. The crowd loved it. Ford loved the crowd. With corporate backing, Shelby subleased the red-brick building at 1042 Princeton Drive to put the car into production.

This was the shop where Woolworth heir Lance Reventlow had built his immaculate but overmatched Scarab Formula 1 cars. Along with the building came Reventlow’s lavish inventory of equipment, from mills and lathes to welders and an engine dyno. But the most valuable asset wasn’t real estate or tools. It was one of Reventlow’s employees.

Phil Remington was the Paul Bunyan of American motorsports. A superlative machinist, fabricator, and mechanic, he worked longer and faster than anybody, and that wasn’t even his greatest attribute. “Rem is a remnant of an age of American ingenuity,” Dan Gurney once said about him. “It doesn’t matter what you’re talking about, he can do it. Tell him what’s wrong, and he creates a solution. So many overnight fixes come to mind that I don’t even know where to begin. He’s just a great, unstoppable force of nature.”

A SoCal hot-rodder who set speed records on the dry lakes of the Mojave Desert before World War II, Remington later worked on Indy cars, F1 cars, and even, in his 90s, the radical DeltaWing Le Mans prototype. Next to Shelby, he was the single most important cog in the Shelby American machine. “Without him,” gearbox wizard Pete Weismann declared, “the program would have been an unbelievable failure.”

Remington was remarkably blasé about his own accomplishments and never thought of himself as a legend. At the time, he didn’t agonize over going to work for Shelby, and decades after the fact, before he died in 2013, he still didn’t see anything special about his decision to join the fledgling operation. “I came with the building,” he said. “I just changed payrolls, I guess you could say.”

Riverside International Raceway, February 2, 1963, the first race of the Cal Club/SCCA season. Shelby American showed up with a pair of Cobras that would look odd to modern eyes—a red one and a white one, both equipped with dainty wire wheels instead of muscular Halibrand mags, and 260-cubic-inch Ford V-8s rather than the gnarlier 289s soon to become standard issue.

By this time, more than 75 Cobras had been built, and cars were being stored in the empty lot across the street. But from the beginning, Shelby understood that racing was in the Cobra’s DNA. It’s no coincidence that virtually every one of Shelby American’s early hires went on to have long careers in motorsports. Later, it was commonplace for people to say that Shelby licked Ferrari with a bunch of Southern California hot-rodders, and that was true to a certain extent. But in the 1960s, Los Angeles was the epicenter of the American racing industry, so Shelby was able to draw from a deep pool of talented and experienced mechanics and artisans.

The team’s drivers were both local heroes, though they’d traveled wildly different roads to stardom. Dave MacDonald had been the most successful of the SoCal Corvette aces. A former dealership mechanic who’d come up through drag racing, MacDonald was a baby-faced assassin whose placid demeanor belied his extravagant tail-out driving style. As a counterweight, Shelby hired Ken Miles, a sardonic British war veteran with a scathing wit. Besides dominating small-bore racing on the West Coast in Porsches and MG specials, Miles was also a self-taught engineer and a test driver par excellence.

In the prelim on Saturday, the Cobras scored Shelby American’s first victory as MacDonald and Miles eviscerated the Sting Rays en route to a 1-2 finish. The beatdown was even worse on Sunday; Miles pitted after an off-course excursion on the first lap, then waltzed through the field to again finish second to MacDonald. Adding insult to injury, Shelby American ran a wicked win ad: “ATTENTION CORVETTE OWNERS! To get rid of that foul taste in your mouth (Cobra exhaust) order a COBRA ‘RIVERSIDE REPLICA.’”

After vanquishing the Corvette, Shelby looked overseas for his next victim.

The Cobra Daytona Coupe

Back in the summer of 1957, Shelby had met Enzo Ferrari in the Commendatore’s office in Maranello. It didn’t go well. Shelby had been winning races in the States in privately owned Ferraris. Now, Ferrari dangled a ride with the factory team in front of him. Usually, prestige alone was enough to seal the deal. But Shelby was a mercenary who “drove race cars professionally in an amateur sport.”

“How much do you pay?” he asked, not mincing words.

“Seventy dollars a month,” Ferrari said immediately.

Shelby felt insulted by the lowball offer, so he blew off Ferrari and signed instead with Aston Martin. And he vowed to one day settle the score with “that old son of a bitch.”

As soon as the first Cobras were built, Shelby made sure the car was homologated by the FIA to compete in the GT world championship. The immense grunt of the small-block allowed the roadster to outrun the competition on tighter American tracks. But the Cobra had the aerodynamic qualities of an aluminum two-by-four, and it couldn’t keep up with the slicker Ferrari 250 GTO on high-speed circuits. “The windshield acted like a huge air brake,” Gurney explained to me years later. “At Daytona, we angled it back so much that we would look over the windscreen.”

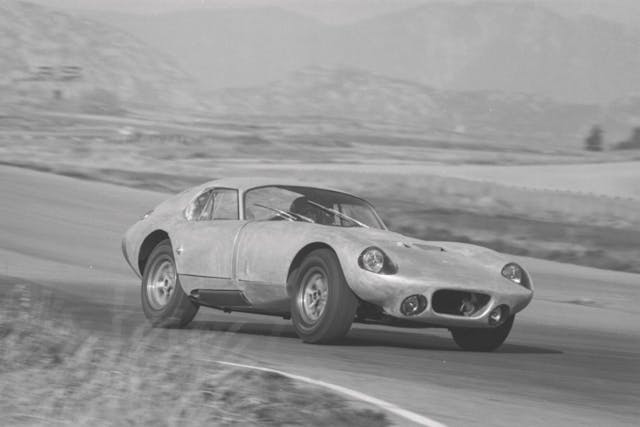

Shelby’s baby needed some new clothes. Enter Peter Brock, Shelby’s first employee. Brock had attended Art Center in Los Angeles and was working at General Motors in 1958 when he sketched the inspiration for the original Corvette XP-87 Sting Ray racer. During his stint at GM, while rummaging around the library, he’d found a German technical document confiscated after World War II describing aerodynamic qualities he thought he could incorporate to fashion a slippery coupe body with an unusual chopped-off rear deck. Brock took the idea with him when he left GM in 1959 to head back to California to join the racing scene.

Shelby, who had hired Brock in 1961, promptly signed off on Brock’s coupe proposal once the Cobra’s aerodynamic shortcomings became obvious. “I don’t care what the hell it looks like as long as it goes fast,” he drawled.

“How much money and how much time do we have?” Brock asked.

“No time and no money.”

Brock recalls: “I didn’t even have a drawing board. I taped butcher paper to the floor in the accounting office, and that’s where I made all the drawings for the wooden buck. I drew it up in quarter-scale. I took 35-millimeter photographs, and I projected the slides onto the wall. AC wouldn’t give Carroll the engineering drawings, so we had to reverse-engineer the chassis.”

Remington thought Brock’s car looked goofy, and his skepticism infected just about everyone in the shop. To be fair, they were distracted, humping to shoehorn a 289 into a mid-engine Cooper Monaco that had arrived from England. Eventually, that British-American mongrel would be dubbed the King Cobra, and after a single shakedown and one abortive race, it was taken to the L.A. Times Grand Prix at Riverside, then the most lucrative sports car race in the world. There, MacDonald, who’d been racing in SCCA regionals only a year earlier, lapped a field that included F1 stars Jim Clark, Graham Hill, and John Surtees.

But the King Cobra was a one-off project. Shelby American was also building FIA-spec Cobras to compete in international GT races as well as cars optimized for the SCCA’s professional U.S. Road Racing Championship, which was duly won in 1963 by factory driver Bob Holbert, Al’s father. (Bob Johnson was crowned A Production champ.) Meanwhile, a second building was leased on Carter Avenue, about 100 yards away, and devoted to street-car production.

Both shops were humming by the end of 1963, driven as much by passion as a paycheck. It wasn’t uncommon for guys to come back to work after dinner, off the clock. Generally speaking, it was a happy environment, full of pranksters like race mechanic Charlie Agapiou, who was fond of lighting off firecrackers, and team manager Al Dowd, who kept a live cobra named Herman in an empty aquarium. But along with camaraderie came groupthink, and the feeling around the shop, following Remington’s lead, was that Brock’s project was a waste of time.

The coupe was marooned in a corner like an unwanted stepchild. The only crewman Brock could enlist to help him was fabricator John Ohlsen, a new hire from New Zealand. Fortunately, the car found a champion in Miles, who’d built his own specials before joining Shelby American. Ignored by everybody else in the shop, the three of them built the car themselves.

On February 1, 1964, Miles tested the coupe at Riverside. He reached a top speed of 180 mph—the roadster had maxed out around 160—and recorded a lap time 3.5 seconds faster than the competition Cobra. Miles called Shelby from the track and reported, “This thing’s a rocket ship.” By the time the coupe returned to Shelby American, the center of the shop had been cleared out so everyone, including Remington, could start working on it.

Two weeks later, Brock’s creation qualified on the pole at Daytona and led until it was engulfed in a pit fire. Ohlsen was under the car when flames erupted (according to legend, he yelled, “I dropped my wallet!” as he slithered out from under it). The Cobra Daytona Coupe, as it was christened, won the GT class at Le Mans, and it might have won overall if it hadn’t been hamstrung by oil-cooling issues. Shelby American would almost certainly have secured the GT world championship if Enzo Ferrari hadn’t deviously persuaded the Italians organizing the race at Monza to cancel the event to prevent the Cobra from winning it.

“It was pure politics,” Shelby complained later. “The old son of a bitch would do anything to win races.

I admired him for that. But when he was doing it to me, that was a different thing. Ford didn’t want me to go back in 1965, but I wanted to win the GT championship. I couldn’t let Ferrari pull that bullshit and get away with it.”

At the end of the season, Shelby held a press conference to discuss his plans for 1965. “Next year,” he growled, “Ferrari’s ass is mine.”

The Mustang GT350

On Friday, April 17, 1964, the Ford Mustang debuted at the Ford Pavilion, a.k.a. the Wonder Rotunda, at the New York World’s Fair. That weekend, 4 million people visited Ford dealerships. About 22,000 of them ordered Mustangs.

Although Ford Division general manager Lee Iacocca was thrilled by the numbers, he wanted to upgrade the car’s image. Spunky bodywork notwithstanding, the Mustang was little more than a tarted-up Falcon with an anemic six-cylinder engine. So, Iacocca asked Shelby to sprinkle some high-performance fairy dust on it.

Shelby didn’t want any part of the project. “It’s a secretary’s car,” he groused.

But Iacocca insisted, and Shelby couldn’t refuse. Shelby American took delivery of its first fastback Mustang in August 1964. Miles pored over the Ford parts catalog for components that could be swapped onto the car. Early on, it was referred to as a Shelby Mustang, but Ford executives thought—not without justification—this name put the cart before the horse. After many fruitless brainstorming sessions, a frustrated Shelby asked Remington how far it was from the shop on Princeton Drive to the one on Carter Avenue. “About 350 feet,” Remington said.

And the GT350 was born. Or so the origin story goes.

The timing was less than propitious. The previous May, Holbert had retired from racing after totaling a King Cobra at Kent, Washington. Two weeks later, MacDonald was killed in a ghastly wreck at the Indianapolis 500. Besides taking on extra driving duties, Miles was messing around with the Sunbeam Tiger and spearheading an effort to retrofit a Cobra with a 427. Adding the Mustang program to the mix threatened to send Shelby American spinning out of control.

It was clear that the scale and complexity of the GT350 project demanded a manager with formal technical training and corporate savvy. To ride herd over the program, Shelby headhunted a young engineer (and talented club racer) named Chuck Cantwell from the GM Tech Center. “That was an odd situation, talking to him about a job that he really didn’t want to provide,” Cantwell says. “Shelby wasn’t too enamored with the idea of having to find a much bigger place and have a bigger organization. He was happy with what he had and with the Cobras.”

With the crew already in overdrive on other projects, Shelby American also needed more bodies to mod the Mustangs. In late 1964, local hot-rodder Bernie Kretzschmar visited the shop just to take a look. “It was crazy,” he says. “I mean, they were testing cars on city streets, and they were running the dyno wide-open even though there was a tract of homes a block away. I don’t know how they got away with all that. Anyway, I decided, while I’m here, I’m going to fill out an application. They had a stack of applications a foot high, but the key questions were, ‘Do you have your own tools?’ and ‘Can you weld?’ And I said, ‘Yes,’ and ‘Yes.’”

Fastback Mustangs painted Wimbledon White arrived directly from the assembly line in the Ford plant in San Jose with unessential items deleted. In Los Angeles, a skeleton crew transformed them into GT350s and GT350Rs, as the race cars were designated. Driven by Miles and wearing striking graphics designed by Brock, the car won in its first outing, at Green Valley Raceway in Dallas. Later, despite running what Cantwell laughingly describes as “a super low-rent operation,” Sports Car Graphic technical editor Jerry Titus shepherded a GT350R to the B Production National Championship.

The next year, the SCCA inaugurated the Trans-Am series. Ironically, the GT350R wasn’t eligible since it previously had been homologated as a two-seat sports car rather than a sedan. Shelby authorized Cantwell to spend a meager $5000 to develop a Mustang for the series—and that included the cost of buying a hi-po notchback from a local dealer. Titus clinched the manufacturer’s title for Ford by claiming the final race of the season, at Riverside, in a car prepped at the last minute by Shelby American. “It was probably the cheapest championship that Ford ever bought,” Shelby American competition director Lew Spencer quipped later.

In 1967, Shelby American defended its Trans-Am title with Mustangs painted what Dallas artist Bill Neale, Shelby’s longtime boon companion, described as “gawd-awful yellow.” The cars were entered by the Terlingua Racing Team, an inside Shelby/Neale joke commemorating a barren South Texas ghost town. (Along the same lines, Shelby liked to tell clueless reporters that he was a bat guano distributor.) Once again, the points battle came down to the last race of the season, and once again, Shelby American drove away with the championship.

It was the last one Shelby would ever win.

The GT40

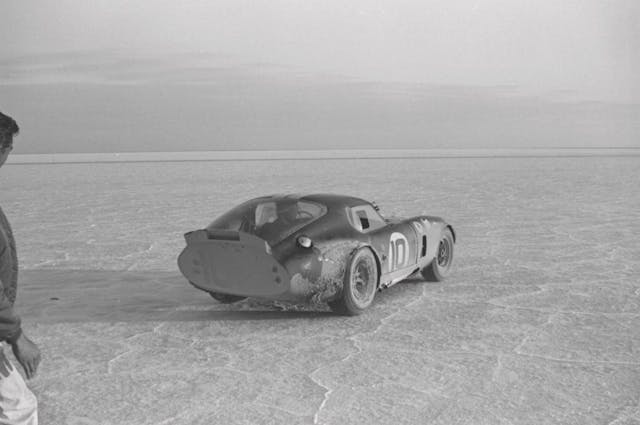

The Bahamas Speed Week was an end-of-the-year, run-what-you-brung race-cum-bacchanal in Nassau. Most of the Ford execs who attended in 1964 were there to enjoy a winter getaway on the company dime, so they weren’t too concerned when they saw Miles’s experimental big-block Cobra roadster blow up early and often. After all, what could you expect of a car known not-so-affectionately at Shelby American as “The Turd”? But they got hot under the collar as they watched a pair of Ford GT40s get annihilated by the Chevy-powered Chaparral and GM-funded Corvette Grand Sport.

The GT40 had been built in England at great expense by a team of Ford engineers and Lola Cars craftsmen. Race operations were entrusted to John Wyer, who’d managed the Aston Martin team in 1959 when Shelby won Le Mans. The car suffered from calamitous teething pains in 1964. When the Ford brass returned from Nassau and convened a postmortem, they concluded that the problem with the GT40 wasn’t the car; it was Wyer. So they fired him and handed the reins to their in-house snake charmer.

Still wearing grime from the races in Nassau, the two cars arrived at LAX in December 1964 and were immediately Shelby-ized, meaning they were painted Viking blue and fitted with 289 Cobra motors and Halibrand mag wheels. Miles tested relentlessly for the next month, with Remington upgrading the car on virtually a nightly basis. After an all-hands-on-deck thrash, Miles and co-driver Lloyd Ruby scored the GT40’s first win at Daytona to start the 1965 season—in fact, it was the first time the car had finished a race.

But this victory flattered to deceive. Le Mans later that year was so disastrous that some Ford execs lost faith in Shelby. Rather than leave all its eggs in one basket for Le Mans in 1966, Ford entrusted three cars to Holman & Moody, which was flying the company flag in NASCAR, and two to Alan Mann Racing, which had run the Cobra Daytona Coupe’s GT world championship team the previous year. Shelby American was responsible for the last three cars, each with its own crew. This fueled infighting in the shop as well as competition on the track with the other Ford teams.

In Ford v Ferrari, the Hollywood-ized (read: largely bogus) version of the Ford GT saga, Miles played a tragic hero while Ford racing chief Leo Beebe was cast unjustifiably as a villain (and Remington, inexplicably, as a dweeb). Before Le Mans, Ford’s imperious CEO, Henry Ford II, had given Beebe a notecard with a handwritten message: “You better win.” By the time everybody got to France, the tension was off the charts. “You had all the Ford guys there, including Henry himself, so it was fairly high pressure,” Chris Amon, who co-drove the winning car, said with characteristic understatement. “I seem to recall having a long talk with Carroll, and he was looking pretty gray, actually.”

The Ford GT Mk IIs, so-called because the 289 had been replaced with 427 big-blocks, scored a 1-2-3 victory marred by the botched photo finish dramatized in Ford v Ferrari. Miles fans and conspiracy buffs insist that the Brit was jobbed out of a victory he deserved. (Miles had been ordered to slow down near the end of the race to allow Bruce McLaren to catch up in a second team car. Although they crossed the line side by side, McLaren was declared the winner because he’d qualified behind Miles and therefore covered 20 more feet on the track.) Shelby himself later said he regretted not ensuring that Miles won. But Miles died in a testing accident at Riverside that August, before Shelby got around to apologizing.

There was hardly any time to mourn. Besides building 427 Cobra S/C models, Shelby American was knocking out Mustangs, including GT350H models earmarked for the Hertz Rent-a-Racer program. So Ford chose to rest on its Le Mans laurels and didn’t bother running the prototypes again in 1966. Then, the 1967 season opened with the upgraded Mk IIB getting demolished at Daytona by the new Ferrari 330 P4. Adding insult to injury, Amon, who’d defected from Ford to Ferrari, described the Mk II as “a truck” compared to the P4.

Back in Dearborn, there was shock and alarm. While recriminations flew back and forth, Remington calmly took one of the unloved and as-yet unraced J-Cars, the car Miles had been testing when he was killed, to the Ford wind tunnel. There, working by intuition, he and two top Shelby fabricators, Bill Eaton and Dennis Bragg, reshaped the ugly duckling into a swan. “We did the work entirely by eye—no drawings, nothing,” Remington said. “Some things just look right, and others don’t.”

The Mk IV, as the rebodied car was named, won its first race out of the box, at Sebring. A Shelby American Mk IV won again in its second and final race at Le Mans, where Gurney and A.J. Foyt steamrolled the Ferraris. One week later, new regulations limiting engines to 5.0 liters were adopted. Hey, if you can’t beat ’em, ban ’em! The victory marked the apogee of American involvement in international motorsports. And it never would have happened without Shelby American.

Growing Pains

By the end of 1964, the Shelby American operation looked like a teenager who’d outgrown his hand-me-down wardrobe. The GT40 program was coming, and Mustangs were slated to be produced by the hundreds rather than the dozens. So in January 1965, Shelby leased a pair of cavernous hangars on Imperial Highway, on the southern edge of LAX, where North American Aviation had built F-86 and F-100 fighter jets—a fitting heritage.

The 12.5-acre site came with 96,000 square feet of space. The west hangar was devoted to race cars, the paint shop, the parts department, and the show-car services Shelby American provided to Ford. The east hangar was outfitted for production of the GT350. A long pit was excavated in the floor to create an assembly line. No longer did mechanics have to crawl underneath cars balanced on jack stands. Instead, Mustangs advanced from station to station on wheeled diamond-plate ramps as GT350-specific components were installed.

Outside, a concrete blast wall separated the facility from the runway and provided a safe space for shakedowns. It was here that Miles performed his famous 13-second zero-to-100-to-zero acceleration-and-braking demonstrations in the 427 Cobra. Closer to the hangars, cars were parked in long, orderly rows. Besides looking impressive in publicity photos, it also created an impromptu racetrack where Gurney and fellow racer Jerry Grant once played bumper tag at 90 mph in GT350s while Kretzschmar and others looked on incredulously.

“All I’m thinking is, ‘Man, if they wreck in there between all those cars …’” Kretzschmar recalls. “After they stopped and we went back to work, somebody hollered, ‘One of the cars is on fire!’ We run out of the hangar, and there’s black smoke coming up from the hood of Gurney’s car. We look around but don’t see any flames, so we dive underneath. Gurney had been standing on the brakes so hard that he’d set the rubber boots around the pistons in the calipers on fire,” he says with a chuckle. “Just another day at Shelby American.”

But Shelby American itself changed after the move to LAX. Vastly increased production meant the company couldn’t be as discriminating about whom it hired. Early on, jobs had been reserved for the best and the brightest, plus true believers like Jim Marietta, who started out by flying to races, sneaking into the paddock, and volunteering as an unpaid crewman. The head count skyrocketed from about 50 to more than 200, with some newbies provided by employment agencies. Working at Shelby American was no longer a calling. It was a job where you punched a clock and wore a company badge.

“The whole thing fell apart,” Marietta says. “Everybody working so closely together promoted congeniality. Once we got to the airport, everything was so spread out. You couldn’t keep track of people anymore. We lost that esprit de corps.” Or as a disgruntled Shelby put it at the time: “It’s gotten too big, and it isn’t as much fun anymore. There’s too much money and too much work—and too many Ivy League suits runnin’ around the damn place.”

From the beginning, inevitably, there had been friction between Shelby’s merry band of hot-rodders in Southern California and the buttoned-down bean counters in Dearborn. And although Shelby had a powerful fan club at Ford, starting with Iacocca, he also had detractors who resented his laissez-faire management style and cavalier approach to money. Other people’s money, that is. It’s worth remembering that, even though GT350s are A-list collectibles now, they were a financial catastrophe that cost Ford hundreds of thousands of dollars back then.

“In the fall of ’66, Ford dispatched their top consultants to California, started firing people, and took control,” says Brian Styles, a muscle car collector who has studied tons of internal Ford documents. “And I think what they realized is, ‘We ain’t going to fix this stuff out here in California.’ They finished off production in May, June, July 1967, pink-slipped everybody, and shuttered the thing.”

The lease at LAX expired in the summer of 1967. Production of the GT350 moved to Michigan, and Shelby American splintered into three separate entities: Shelby Automotive, Shelby Racing, and Shelby Parts. The team raced in Can-Am in 1968 and Trans-Am in 1968–69, but with ever-diminishing returns. After dominating Le Mans with the Ford GTs, Shelby couldn’t dredge up much enthusiasm for a weekend at War Bonnet Raceway Park in desolate Mannford, Oklahoma. By the end of the decade, he’d left racing behind and was hosting chili cook-offs in Terlingua and enjoying safaris in Africa.

Today, cars from the Shelby American menagerie are among the most reliable collectibles in the world. According to the Hagerty Price Guide, a “humdrum” condition #1 Cobra with a 260-cubic-inch engine and worm-and-sector steering is worth $950,000. A 1963 289 with rack-and-pinion steering goes for $1.4 million, while a 427 S/C, which was virtually unsellable when new, will now cost you $2.9 million. Looking for a base-level GT350 from 1965? Expect to pay $600,000, and twice that for an R model. Competition cars are even more stratospheric; a Daytona Coupe sold for $7.7 million back in 2009. Now it might top $30 million.

It’s not hard to understand why these cars are so highly prized. They offer unrivaled curb appeal and sound totally badass. Generally speaking, performance is on par with modern supercars until you get into territory where aerodynamics are critical. Each car was built by hand, so no two are truly identical. The fact that every car is imbued with a bit of Shelby’s magic and carries the imprimatur of America’s greatest road-racing factory adds a premium to the price.

Shelby American was in the right place at the right time, when money from automakers and big-time sponsors funded technology that revolutionized the sport. At Shelby American, they didn’t obsess over the shape of a front-wing end plate, as they might today. They built entire cars. From scratch. Often without plans or direction. “When we were working on the Daytona Coupe, it wasn’t that big a deal to Shelby,” Brock recalls. “It was just one of 35 projects he had going on at the shop. Guys would work on something for six months, and he’d just forget about it. He was ruthless about choosing what to go ahead with, but he usually chose wisely.”

Standing with John Morton in the Princeton Drive building amid office cubicles and sound-editing equipment, I can almost hear Bill Likes running a 289 on the dyno, Jerry Schwarz flaring a Mustang wheel well with an air hammer, and Charlie Agapiou tossing a firecracker at an unsuspecting mechanic. And I can imagine a lanky Texan sauntering down the stairs and speaking directly into the camera for a commercial. “My name’s Carroll Shelby,” he drawls, “and performance is my business.”

I heard that Shelby originally talked to GM for the engine however he was rejected due to conflict with Corvette.

excellent article, conspiracy theorist’s are an over used word these days, Ken Miles Won Le Mans in ’66, best regards A NON conspiracy theorist, albeit a TRUTH and JUSTICE fighter and of course a car enthusiast and Ford/Shelby is my passion no 1 in the automotive world, much love from Norway <3 PS Tom Cotter's Barn Find Hunter series are a thrill to watch, thank you so much for that show 🙂