Media | Articles

How well do you know America’s first front-wheel-drive cars?

“First,” when it comes to automobiles, is tricky to define. Who should we credit with the first front-wheel-drive (FWD) automobile: the inventor, the person (or company) who first conceived of the technology? The first person or company to build a functioning FWD vehicle? The first to bring a practical vehicle to market, regardless of sales volume, or the first to find market success with the idea? As with many inventions, each of those questions may have a different answer.

Here is your primer to America’s first front-wheel-drive automobiles, focusing on the two vehicles that lay claim to the title: The Cord L-29 and the Ruxton.

Front-wheel drive, est. 1770

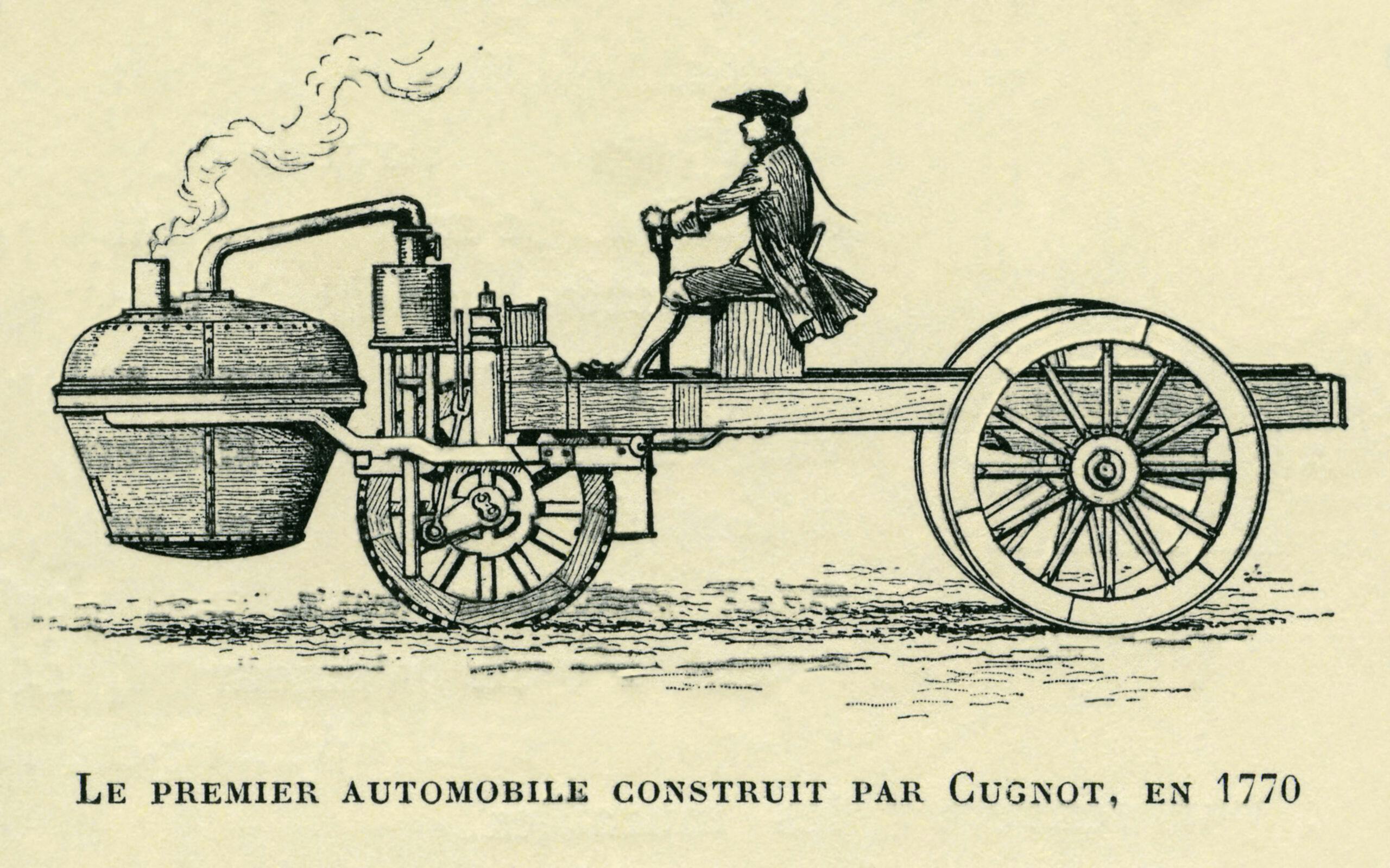

For a feature that’s been sold as a modern advancement since Saabs and the original Mini came on the market, front-wheel drive is quite old. You might be surprised to find out that it dates to what is considered the earliest self-propelled vehicle, the steam-powered, three-wheeled carriage made by Frenchman Nicolas Cugnot in 1770 for hauling freight. (He devised a scaled-down prototype a year earlier.)

In 1894, a fellow countryman named Lepape introduced a front-driven, rear steering vehicle that could either carry passengers or pull trailers and carriages. George Selden, who tried to monopolize automobile manufacturing under a patent that was successfully fought by Henry Ford, introduced a car with a gasoline engine, mounted on the front axle, that drove the wheels through spur gears. Electric front-drivers were made by Barrows and Morris-Salem before the turn of the 20th century. Other brass-era FWD cars were the 1900 Auto Fore-Carriage, the 1901 Phelps Steam Carriage, the 1901 Tractomobile Steam Carriage, 1904 Healey & Co. electrics, and the 1905 Cantono Electric.

Refining FWD on the race track

Perhaps the most notable early FWD pioneers were J. Walter Christie and Harry Miller, who both proved their designs in racing. Christie, who is perhaps better known for designing military equipment like gun turrets and a tank track drive and suspension that was used by many of the combatants in WWII, first patented his front-drive design in 1904. His actually predicted how many FWD cars are laid out today, with a transversely mounted four-cylinder engine, and the transmission and final drive behind the engine driving the front wheels via short drive shafts.

Christie used universal joints because that was about the only way, in his day, to allow the suspension and steering to work. However, U-joints are not ideal in a front-wheel-drive application because the speed of the output side varies as the joint operates. Not for decades after Christie’s patent would constant velocity joints be developed.

Christie founded the Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company, ostensibly to go into the taxi-building business. He only built three taxi cabs, however, before turning to competition. He built seven racers, all with front-wheel-drive systems of his own design and powered by two-, four-, and eight-cylinder engines, including V-4s and V-8s. With almost three-quarters of the cars’ weight on the front wheels, they had plenty of traction but were rather difficult to drive.

That didn’t stop people from wrestling the cars to speed records, though. In 1907 a Christie race car claimed the dirt track mile record of 69.2 mph, and on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s newly brick paved track, a Christie vehicle set the record for the flying mile at 97.6 mph. Years after Christie’s company had given up on making taxis and turned to military gear, in 1915 racing hero and daredevil Barney Oldfield (“My only life insurance — Firestone Tires”) went 113.9 mph on the board track at Tacoma, Washington, in one of Christie’s front-drive racers. A year later he set a new lap record at the IMS at 102.6 mph.

Harry Miller’s name is truly legendary in American racing, though ironically he may be best known for an engine that bears another man’s name: Offenhauser. In the early 1930s, when the American Power Boat Association tried to control Depression-era racing costs with a new 151-cubic-inch displacement class, Miller chopped his DOHC inline-eight in half. Though the resulting four-cylinder was not lightweight, the engine’s advanced valvetrain made it popular with auto racers. When Miller’s company became insolvent, his employees Fred Offenhauser and Leo Goossen continued its development, turning it into a mainstay of American open-wheel racing into the 1970s.

Not as well known as the “Offy” engine is the fact that Miller raced front-wheel-drive cars at Indy for 25 years. In 1924, driver Jimmy Murphy came to Miller with the idea that by using front-wheel-drive and eliminating the driveshaft to the rear axle, he could mount the heavy engine and transmission lower and build a race car that would corner better due to a much lower center of gravity. Following the lead of FWD pioneer Ben Gregory (most notable for his design of the aluminum-intensive Mighty Mite mini-jeep for the U.S. Marines), Miller used a de Dion front axle and then designed a novel, compact transverse transaxle incorporating the transmission and final drive in one unit. The resulting vehicle did not have the weight balance problem of Christie’s earlier racers, was just 36 inches tall (4 inches shorter than a Ford GT40), and weighed just 1500 pounds. A second Miller FWD car placed second at the 1925 Indy 500, averaging just over 100 mph.

The design was so sound that one of Miller’s FWD cars raced actively for more than two decades and his FWD cars raced fairly successfully at Indy for 25 consecutive years. In 1928, Leon Duray set a world’s closed-course record of 148.17 mph in a Miller FWD at the Packard Proving Grounds (a 2.5-mile track very similar to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway) outside of Detroit , a record that held for 24 years.

Harry Miller was also behind one of the most beautiful racers ever, the FWD Ford V-8 race cars that Miller teamed up with Preston Tucker and Henry Ford to build. Unfortunately, schedules didn’t allow sufficient development. The unfettled cars all DNF’d, greatly embarrassing Ford, which permanently killed the project.

Traction Avante-Garde

Meanwhile, back in France, Jean-Albert Gregoire and Pierre Fenaille developed the Tracta constant velocity joint and introduced it in 1926. Instead of the rather primitive universal joint, which has two yokes joined by a gimbal, a CV joint has inner and outer faces, like a ball bearing, only instead of smooth surfaces, the races have grooves across their faces with balls that lock the races rotationally but allow the joint to flex. As the name implies, that keeps the rotational speed of both parts the same. European makers Bucciali, DKW, Adler, Imperia, and Rosengart adopted it for their own FWD cars. Of course, the most successful early FWD to use CV joints car was the Citroën Traction Avant, first introduced in 1934, which went on to sell over three-quarters of a million units.

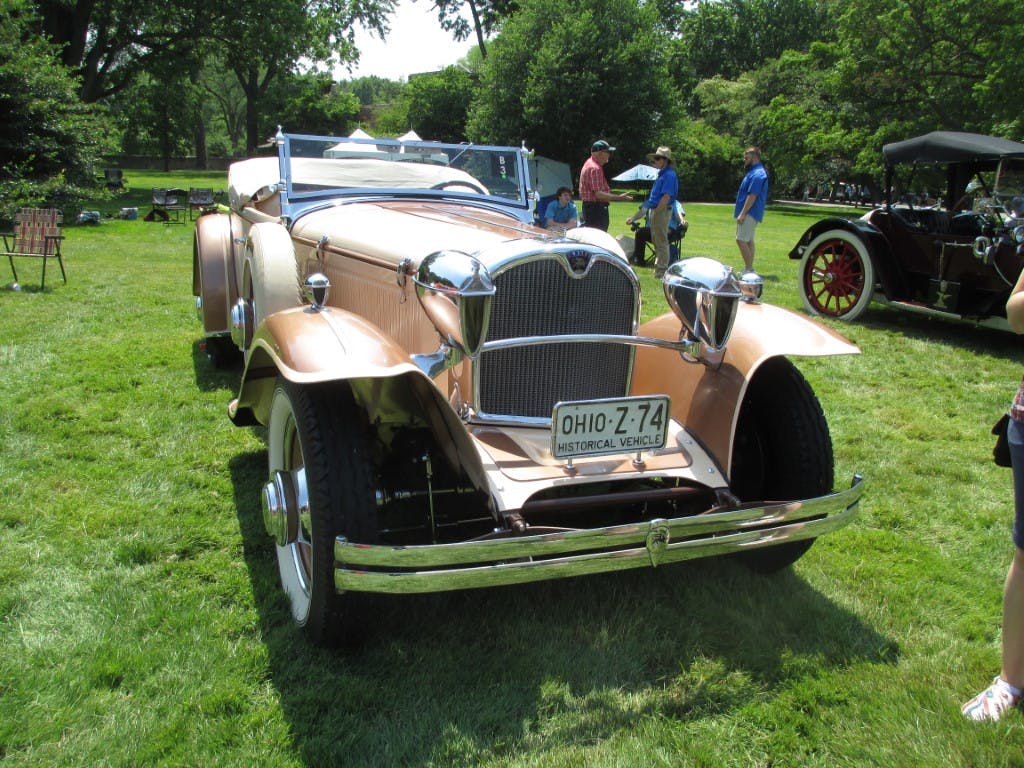

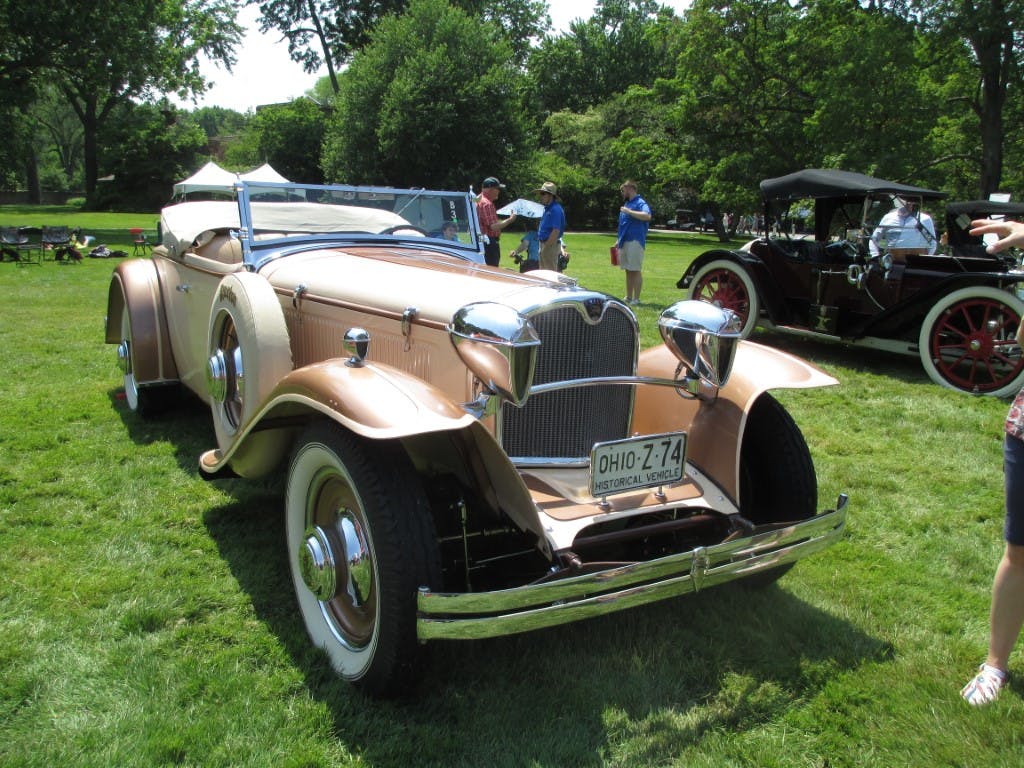

The first American car to use constant-velocity joints, the Cord L-29, wasn’t as big of a sales success as the Traction Avant: Cord sold a little over 5000 examples. Introduced, as the name suggests, in 1929, the L-29 beat the front-wheel-drive Ruxton to production by a matter of months. The Ruxton barely made it to market, with less than one hundred estimated to have been built. Fewer than 20 remain today.

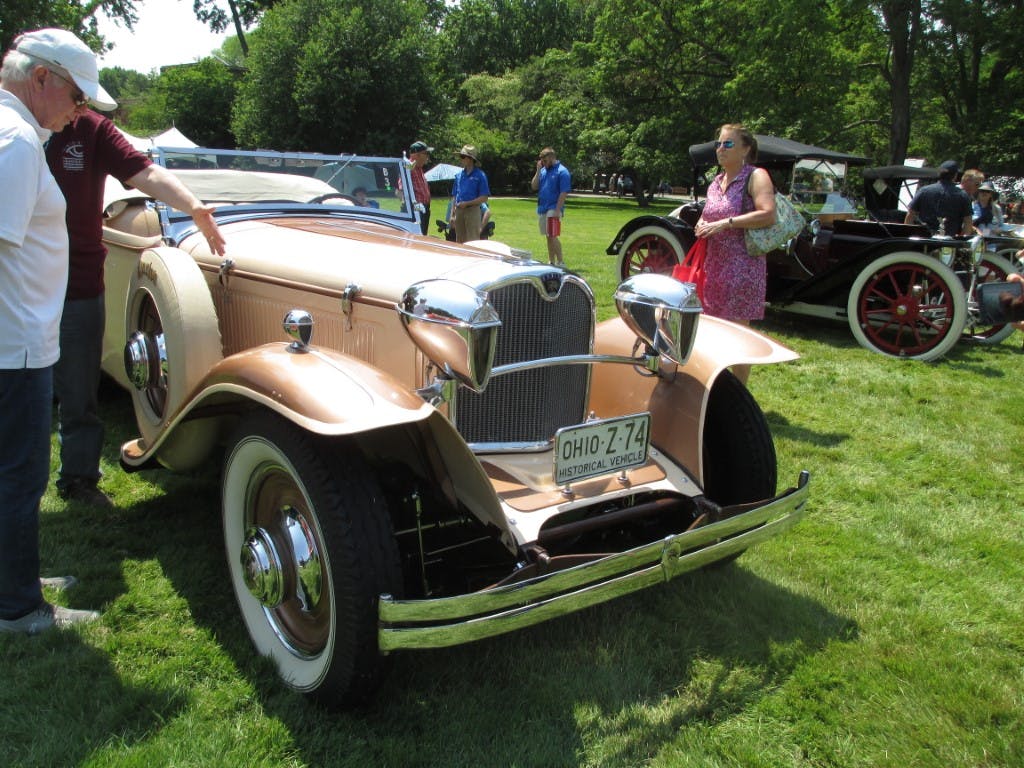

At this year’s Eyes On Design at Ford House, one of the premier auto events in Detroit, the theme was Design Revolution. With their unconventional drive layouts and low-slung bodies, the L-29 and Ruxton were logical entrants. While the Cord is one of the mainstays of the pre-war classic-car scene, at least on this side of the Atlantic, a Ruxton is a rare sight. Seeing the two front-wheel-drive pioneers side-by-side is an even rarer opportunity.

More details on the lesser-known Ruxton to follow. First, let’s get a brief synopsis of the first Cord-branded car, America’s first production front-wheel-drive automobile.

Cord L-29: A case of bad timing

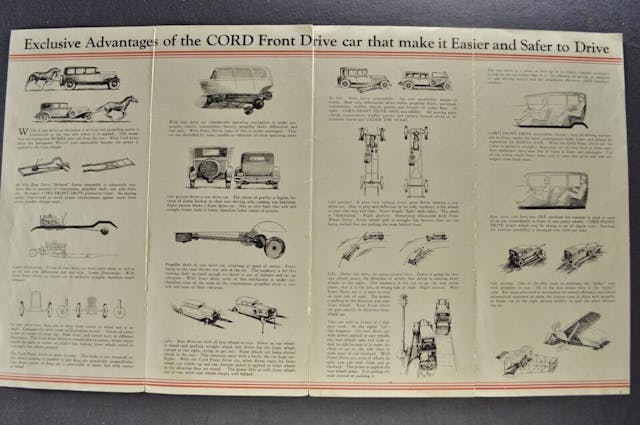

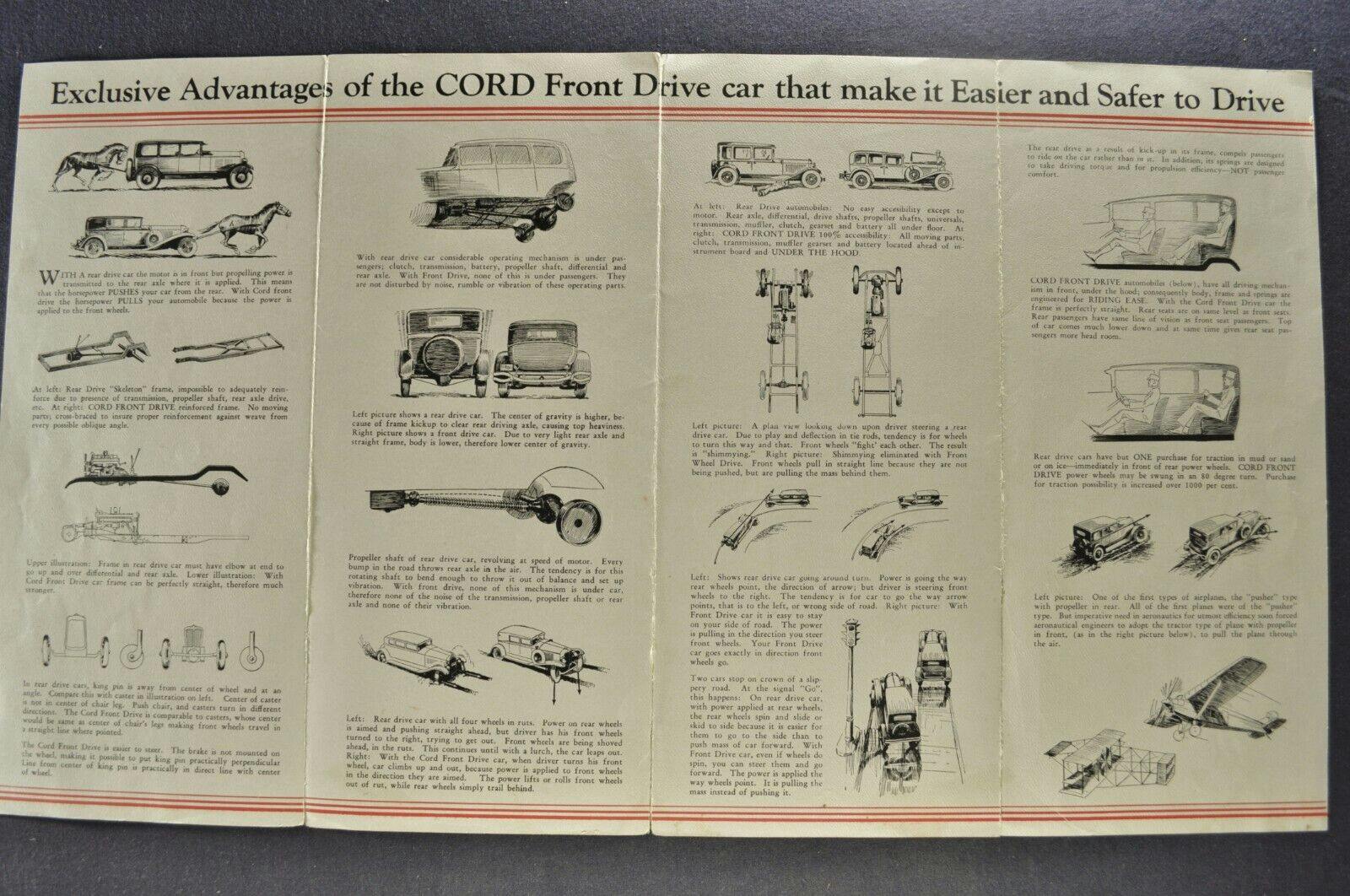

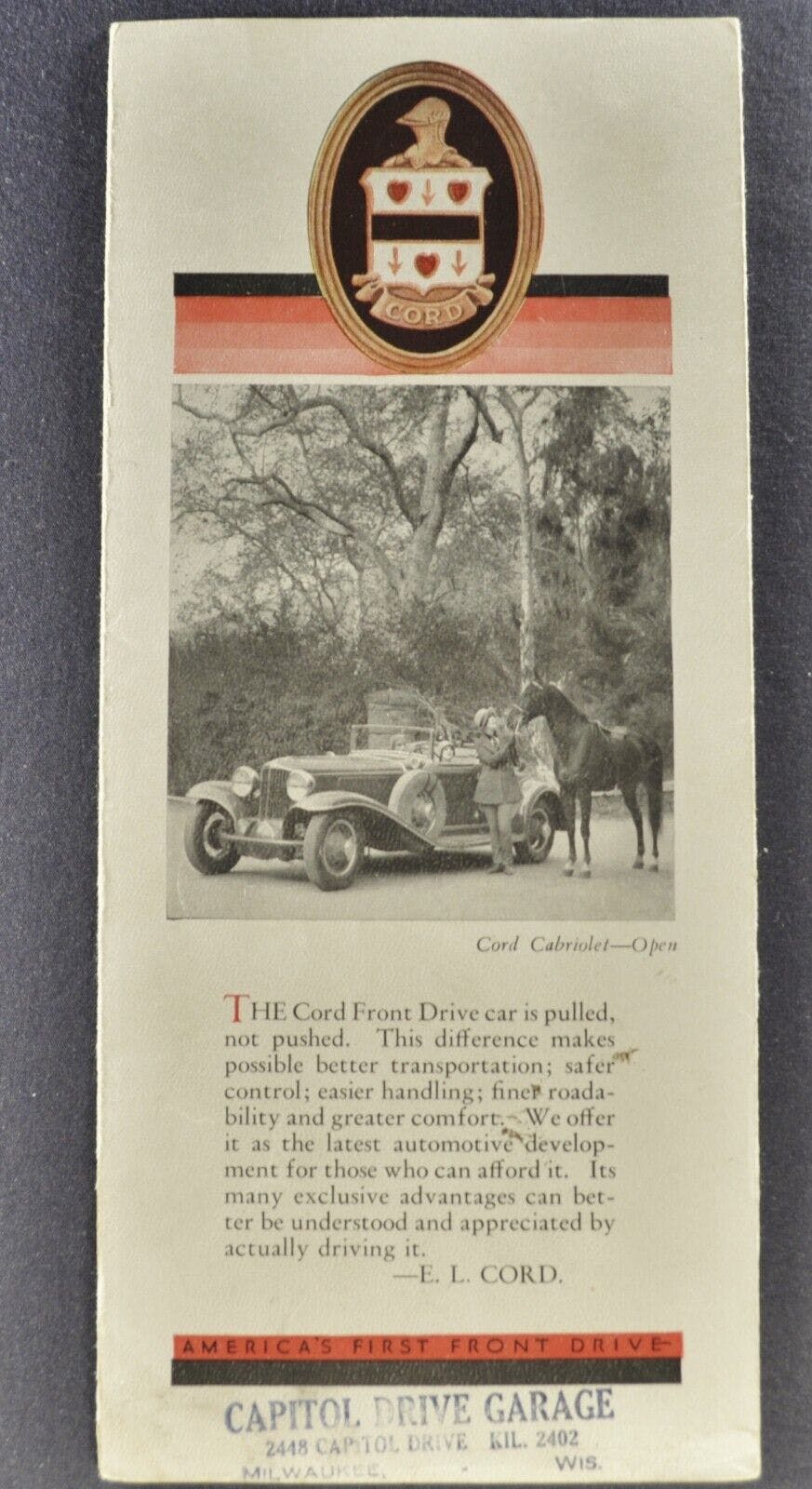

While front-wheel-drive was seen as an advancement in technology, the first makers of those vehicles harkened back to the horse-drawn era in their advertisements. The Cord L-29 owner’s manual exclaims, “This car is not an experiment. In drawing the burden instead of pushing it, it simply reverts to the natural method of moving a wheeled conveyance.” Putting the horse before the cart, so to speak.

Advertisements listed the advantages of FWD—some of them practical, some of them at least a bit hypothetical, including reduced steering effort and strain on the springs, chassis, and body; reduced thrust on front wheel bearings; reduced likelihood of skidding; improved tire wear; and better body stability with reduced pitching.

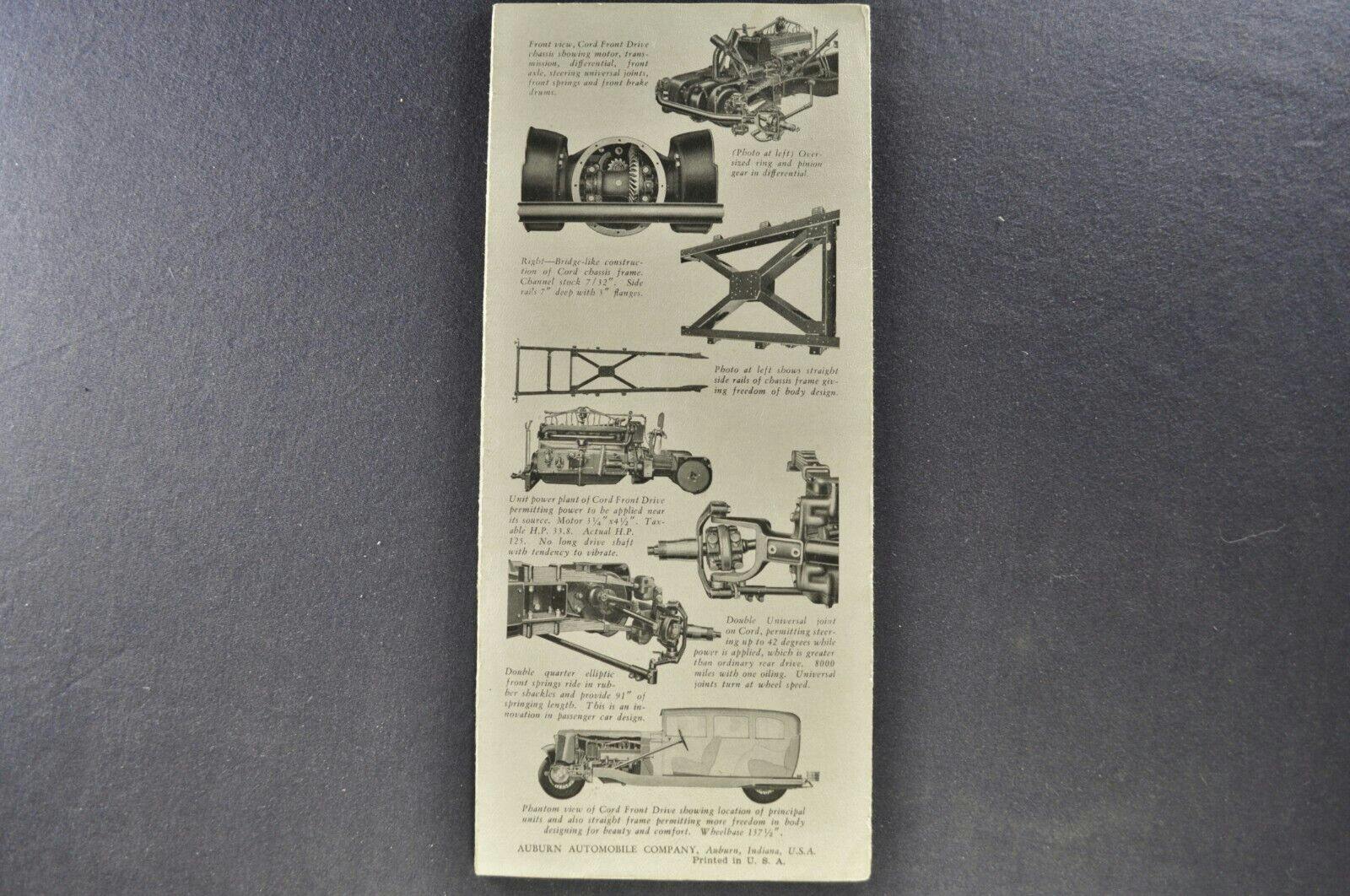

In any case, with all the genuine technological advancements needed to make FWD vehicles, it seems that the primary motivation of automakers to build FWD passenger cars was styling freedom and user convenience. The lack of a driveshaft and rear differential means that the body of a FWD car can sit lower on the chassis, giving the vehicle sleeker styling and making it easier to enter and exit. In the case of our Cord, the fact that the drivetrain would incorporate a straight-eight engine from Lycoming (part of E.L. Cord’s industrial empire) behind the transmission and final drive at the front of the car meant the hood and cowl would be stretched out, making the L-29 look even sleeker.

Errett Lobban Cord was a very smart and successful businessman, a pioneer in many industries. He was smart enough to know who to hire. When he wanted the Auburn company, which he controlled, to have a luxury brand, he brought the Duesenberg brothers under his corporate umbrella. He hired notable designers like Alan Leamy and Gordon Buehrig to design Auburns, Cords, and Duesenbergs. Likewise, when he wanted to make FWD cars, he turned to the person in America with the most experience with that drive layout: Harry Miller.

Cord bought the rights to adapt Miller’s race car design to road-going automobiles. However, he soon discovered a couple of things that are still true today: Racing technology doesn’t always work on the streets, and function doesn’t always follow form. Leon Duray, one of the era’s leading race car drivers, suggested to Cord that he contact one of Miller’s competitors, Cornelius W. Van Ranst, because Van Ranst’s FWD Detroit Special racer was considered easier to drive. Cord hired Van Ranst to design a FWD passenger car. To give some indication of his power as an industrialist, he sent Van Ranst out to California to supervise the prototype’s construction, a process supervised by none other than Harry Miller and Leo Goossen. The L-29 still ended up using Miller’s basic layout, with a de Dion axle and inboard drum brakes.

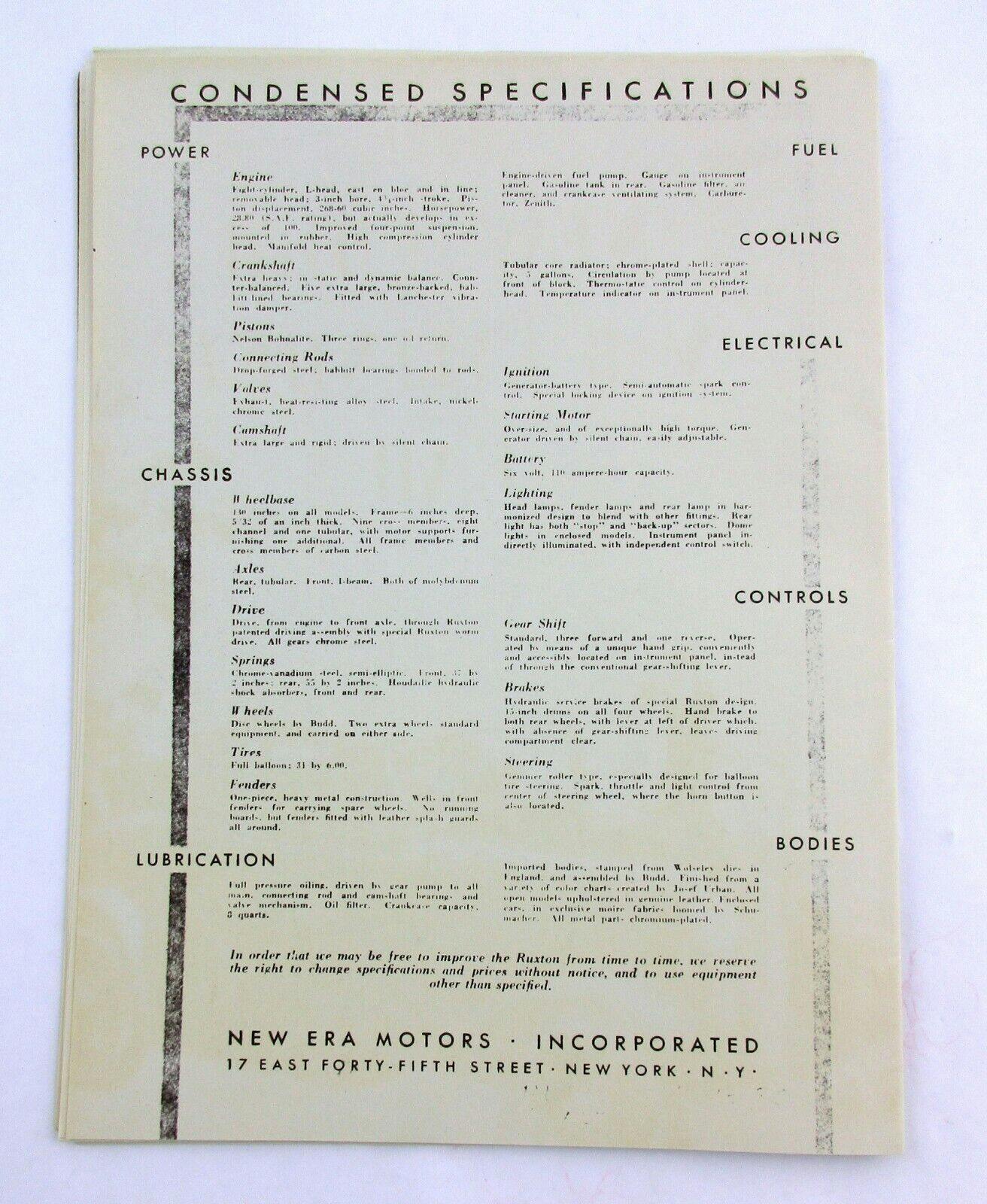

Despite VanRanst’s contributions, the first prototype of the L-29 was difficult to drive. The turns at Indianapolis Motor Speedway are wide and sweeping, and they do not expose the limits of U-joints: Streets with acute corners and tight parking spots do. After switching to the newly available constant velocity joints and fixing other problems with the initial design, VanRanst was made chief engineer of Cord. Though it’s celebrated today as a pioneer, the L-29 was, VanRanst felt, a bit cobbled together. Using an engine designed for rear-wheel-drive and mounting it longitudinally in a FWD layout means putting the flywheel and output shaft on the front of the engine, thus making access to the timing gears and chain difficult—not a big deal today, but a huge inconvenience in an era when things needed frequent adjustment and replacement. Putting the transmission and final drive in front of the engine also created issues with weight distribution. Conventional parts were adapted to reduce costs, but there were still many bespoke components for the L-29.

The 298-cubic-inch engine produced 125 horsepower. Period publications gave the L-29 a top speed of anywhere between 77 and 90 mph, I suppose depending on the testing conditions. Despite Cord’s claims that it produced better traction, the long drivetrain resulted in too much rear-weight bias and the car struggled to climb hills.

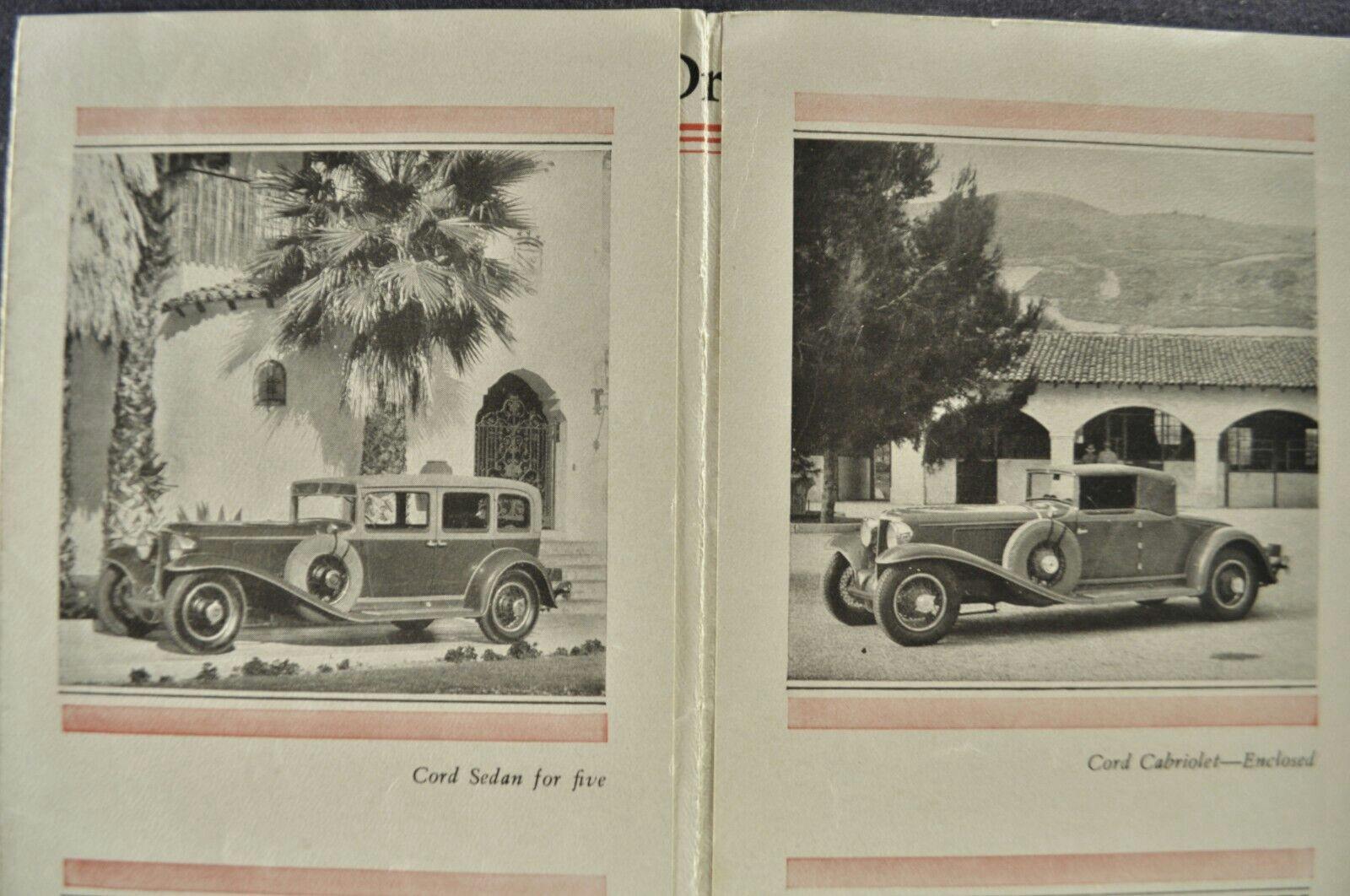

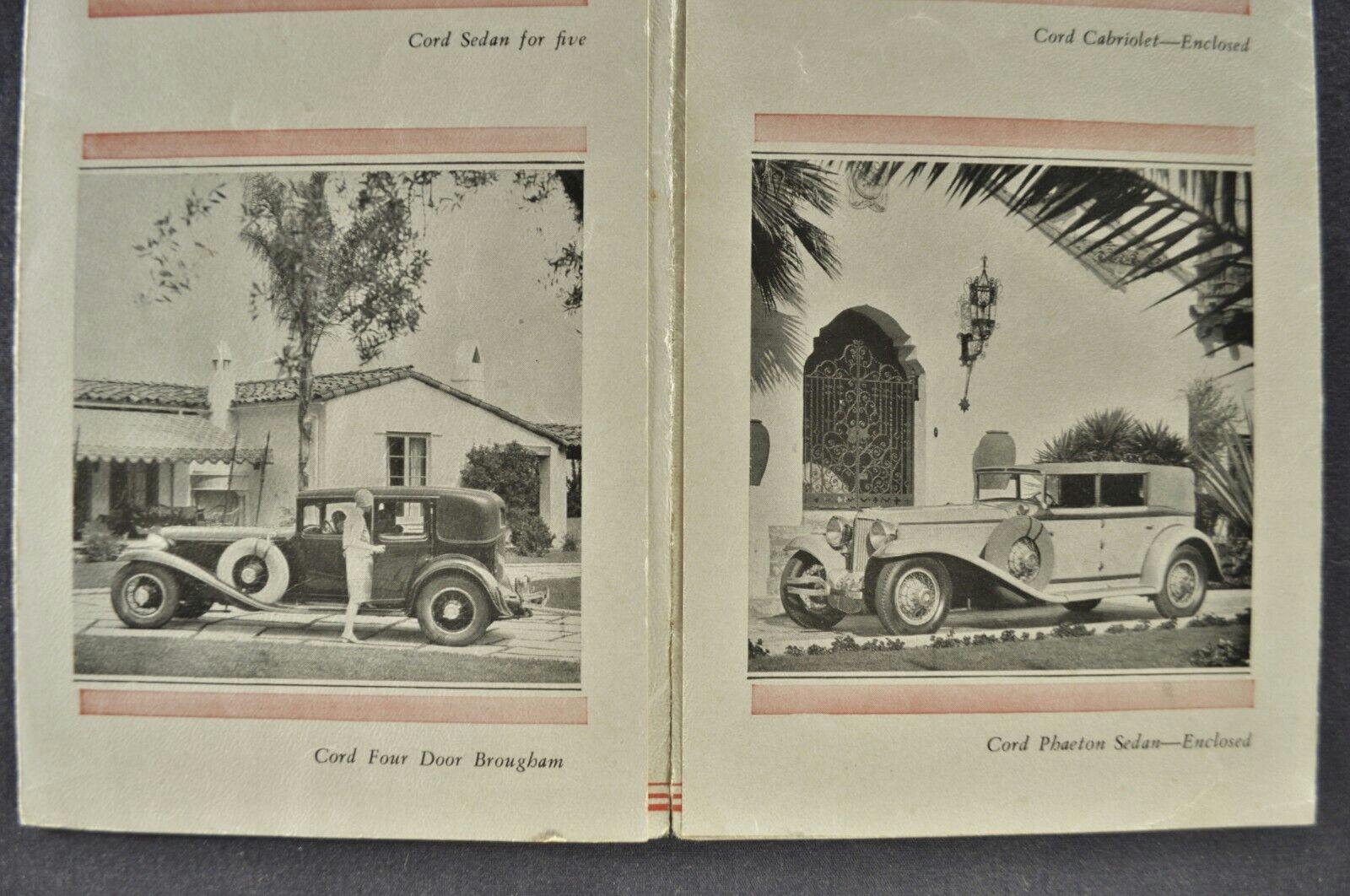

Still, the long hood, and rakish stance made a good canvas for in-house body engineer John Oswald, with Alan Leamy adding touches like the radiator grille. Factory bodies included a six-window sedan, a four-door brougham, a convertible sedan, and a convertible coupe. Coachbuilders like LeGrande, Murphy, LeBaron, Hayes, Weymann, and others made L-29 bodies for the carriage trade.

E.L. Cord hoped to sell 5000 L-29s a year but unfortunately, he introduced the car with a price of $3095 to $3295 … in September, 1929. That works out to about $56,000 in 2023 dollars—well out of economy-car territory, but not prohibitively expensive. The problem was that the new Cord was introduced just a month before the stock market crash that brought on the Great Depression. Fewer than 800 were sold in the first year, and just over 5000 were produced during the three years that the L-29 was in production. To give you some perspective, slightly fewer than 3000 Bricklins and about 9000 DeLoreans were made. While not a sales success, the Cord L-29 was certainly a historically notable car.

Ruxton: A shaky foundation

While the Cord L-29 was the result of an automaker trying to expand his product line, the idea for Ruxton didn’t originate at a car company, but rather at a supplier hoping to sell components to automakers. That explains the Ruxton’s convoluted history, which includes being named for someone who ended up having nothing to do with the vehicle.

The father of the Ruxton was William J. Muller, who worked in the experimental department of the Edward G. Budd Company. In the early days of the automobile, most car companies did not make their own bodies; they bought them from suppliers like Budd (now part of Germany’s ThyssenKrupp group), Murray, Briggs, or Fisher Body. The Budd company was founded by its namesake along with engineer Joseph Ledwinka, a distant relative of the better-known Hans Ledwinka, of Tatra renown. Budd and Ledwinka met while working at Hale & Kilburn company where they pioneered the method of pressing body panels out of steel. In 1912 they set up their own company in Philadelphia, adding power hammering, drawing, and stretching to the body-building process. When the Dodge brothers started making their own cars in 1914, it was Budd who supplied the body panels.

By 1920, the Budd company was well established enough to have an experimental department, which Muller joined that year, after spending some time in motorsports. Aware of Harry Miller’s racers, Muller thought that the FWD concept would work for road cars, and in 1926 he suggested to Edward Budd that the company develop a front-wheel-drive system that it could then sell to one of the larger car companies. Budd was so enthusiastic about the idea he directed Muller to do more than develop a drivetrain: He wanted Muller to build a completely functional prototype that could be used as a demonstrator.

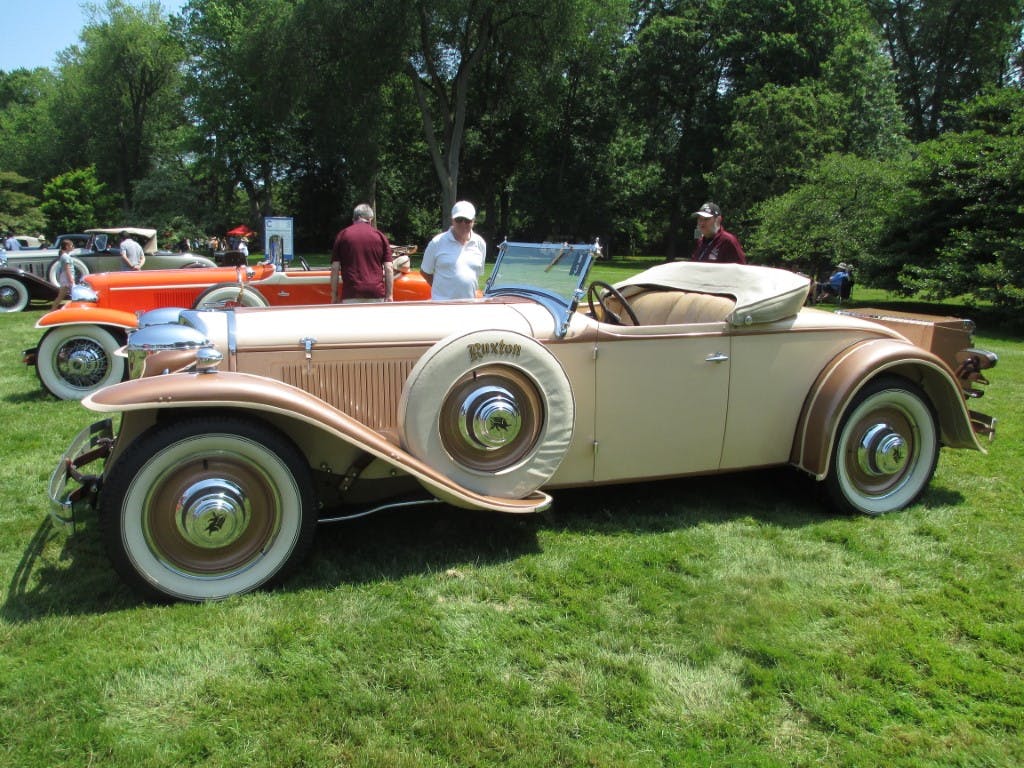

Joe Ledwinka was brought into the project to design and engineer the bodywork of the prototype. Starting with a set of sedan body stampings supplied by the Hupp automobile company, Ledwinka channeled the body, much as hot rodders and customizers would do decades later. The new body was almost a foot lower than that of a typical sedan, meaning the team could get rid of the running boards as well. The result was a sleek, modern-looking car whose novelty was emphasized by custom Woodlite headlamps, which were offered as an option. Sometimes described as “cat-eye” headlights, the Woodlite’s elliptical design was supposed to reflect more light forward but in fact they worked worse than conventional round headlamps.

The Budd prototype was powered by a six-cylinder Studebaker engine driving through a Warner three-speed transmission (though Muller was working on an in-house design for the production gearbox). Revealed in 1928, the prototype received considerable praise—enough for Budd board member Archie Andrews to take notice.

A Wall Street trader, Andrews was one of the Budd firm’s major shareholders and a man with a seemingly deserved notorious reputation. While Edward Budd was out of town in early 1929, Andrews got Muller to transport the prototype from Philadelphia to New York City, where Andrews hoped to use it to raise money to start a car company to put an entire FWD car into production. Andrews didn’t have a factory, so he made a deal with Hupp to develop and produce the car.

To improve traction by shortening the drivetrain, Muller devised a novel transmission that located first and reverse gears in front of the differential and second and third gears between the final drive and the engine. Unfortunately, the deal with Hupp lasted only one month: Not only did Andrews have to find another manufacturing partner, but he also needed investors, so he incorporated a new company called New Era Motors. While publicizing the new company, Andrews took pains to note that the new car would not be branded New Era—it would be named after a potential new investor. The mystery created even more publicity.

The investor that Andrews had in mind was William V.C. Ruxton, a Wall Street banker with what today we would call name recognition. Andrews and Muller showed Ruxton the prototype vehicle. Ruxton expressed enough interest that some kind of deal was agreed between Andrews and Ruxton. To Ruxton’s chagrin, however, Andrews immediately announced that the new car would be named after the investor, who was apparently unaware of Andrews’ branding plans. Ruxton not only withdrew from the agreement but he also sued Andrews, unsuccessfully, over the car’s name.

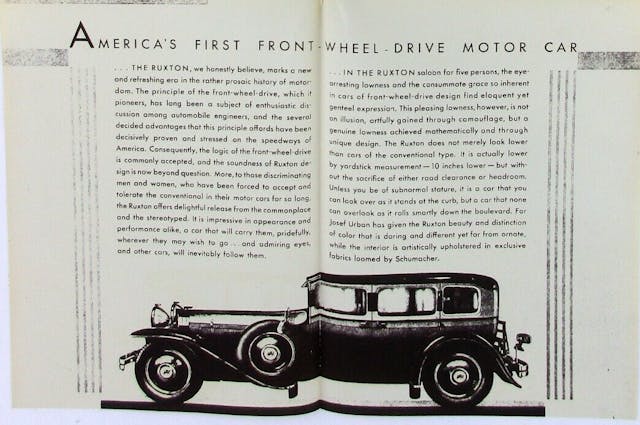

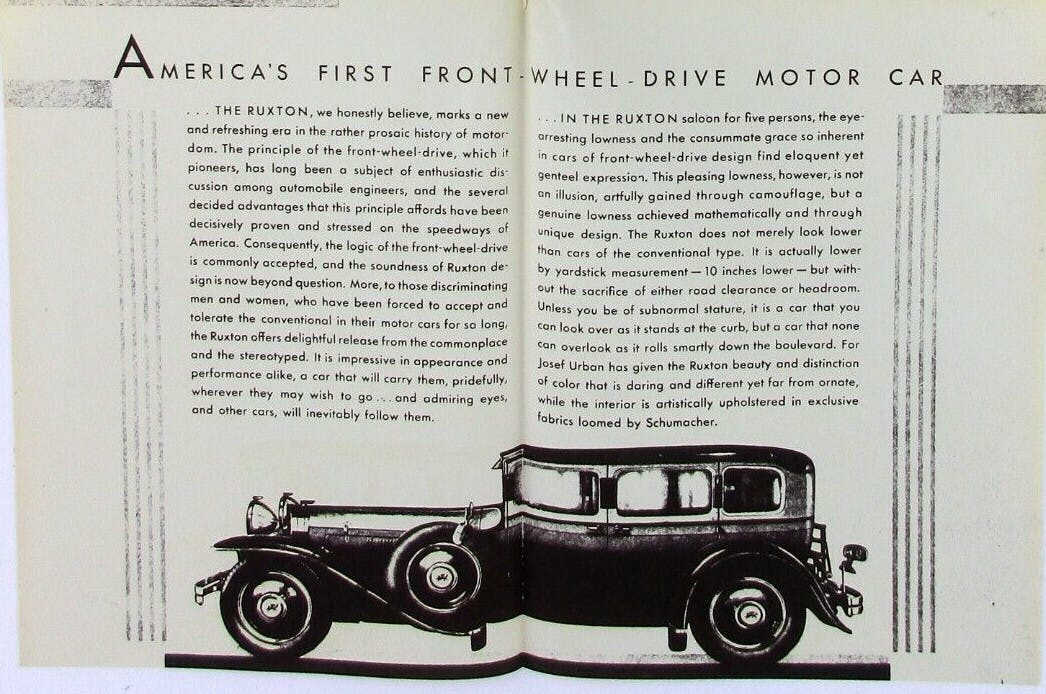

With a respected, but not quite authorized, brand name in hand, Andrews started a widespread publicity campaign, with a four-page advertisement reading, “Utterly Different is the Ruxton and Ten Inches Lower than Any Other Motor Car.” The timing of the campaign was entirely coincidental: Andrews had no idea the Cord L-29 was going to be launched just a month later, or that he differences between the use of Muller’s design and Harry Miller’s patents meant that the Cord wouldn’t be quite as low as the Ruxton. While Archie Andrews may have beaten E.L. Cord to the market, it was the L-29 that started production first. In fact, the Ruxton was lucky to start production at all.

Production of the Ruxton was delayed because Andrews still had trouble finding a company to make the car. Deals with both the Gardner Motor Company and the better-established Marmon firm fell through. Relations with the Moon Motor Car Company of St. Louis were cordial until a dispute led to Andrews manipulating Moon stock, buying it, dumping it to drive down the price, and then buying it back. The dispute eventually resulted in a standoff between Pinkerton security men hired by Moon and the St. Louis police backing Andrews. The dispute was somehow settled in Andrews’ favor and he took control of Moon.

Andrews was obviously a better promoter than manufacturer. He asked designer Joseph Urban, famous for his Broadway set designs, to come up with bright, multicolored schemes for the exterior paint, and Schumacher of New York City was commissioned to supply the interior fabric and upholstery.

A second prototype with a Baker-Rauling roadster body was shown at the New York Grand Central Palace auto show at the end of 1920, followed by three additional Ruxtons displayed at the Chicago Auto Show in early 1930 and an Urban-liveried model at the 1930 New York Auto Show.

While Andrews’ advertisements claimed an initial production run of 12,000 cars by the end of 1929, series production had still not started by New Year’s Day 1930. Production was further delayed because parts ordered earlier were rendered obsolete by Muller’s continued development of the drivetrain.

In finalized production spec, the Ruxton was powered by a straight-eight made by Continental, displacing 4.4 liters and making 100 horsepower—nothing to sneeze at in the early 1930s. Standard bodies included the Baker-Raulang roadster and a sedan sourced, a bit ironically, from Budd. The price of both models was $3195, comparable to that of the Cord.

As he was promoting the as-yet-unnamed automobile, Andrews tried to drum up publicity by using a big question mark as the hood ornament on the original prototype. Once it was named Ruxton, the car got a proper mascot: a griffon radiator cap, and a griffon badge on the radiator cowling. Even the Woodlite headlights were customized with subtle griffon wings. The mythological griffon, which combined a lion with an eagle, was said to guard treasures and priceless possessions.

Moon Motor Company did not have the capability to take the Ruxton to series production, but that didn’t matter, in hindsight: The stock market crash of October 1929 would soon arrive. Andrews, true to character, sought to exploit the financial collapse.

Andrews’ latest, and last, partner would be Kissel, who originally was contracted to make the Ruxton drivetrain components. Soon after agreeing with Andrews to produce the Ruxton for Moon Motors, the Kissel brothers (George and Will) discovered that Andrews was up to his old schemes: He wanted to take control of the Kissel company. The brothers snookered Andrews by placing their company into voluntary receivership, forcing Moon Motor into bankruptcy. New Era Motors filed for insolvency less than a week later.

Despite financial shenanigans and a shaky foundation, the few automobiles produced by Ruxton were pretty good cars. While the Ruxton brand pretty much killed their company, George and Will Kissel kept their personal Ruxtons, which they continually praised.

Based on period publications it was originally thought that perhaps as many as five hundred Ruxtons had been built, but brand specialist and historian Jim Fasnacht says that no more than 96 were produced and even some of these were completed after the bankruptcy of Moon and New Era Motors. It is now thought that no more than 40 Ruxtons were actually sold to customers. Nineteen Ruxtons are known to have survived.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I saw a Cugnot reproduction at an event. Neat car but not all that stable. It rolled over in a garden and I figure it may have been one of the oldest car wrecks ever. FWD did little good.

As for the others Back in the day FWD worked when suspensions were basic and tires were limited. But today I really love my RWD as for me it is so much more manageable.

In the snow I can steer with the wheel or the throttle. The weight transfer unloads the weight on the nose anyways.

FWD is fine for those not coordinated enough to control the front and rear. It is a point and gas system. But If you have good car skills the RWD is the way to go.

Many cars today have stability control to handle the understeer of a FWD car where you can lose steering and brakes if locked up.

Having driven both RWD and FWD in the snow for many, many years in the Midwest, I can say that I far prefer FWD for its much greater starting traction on all but the steepest hills. My VW Beetles were great for starting traction, but their turning or braking in snow were not so great – not enough weight on the front. On dry pavement, they handled well (1969 and after, with semi-trailing arms) and stopped well, with the front accepting quite a lot of weight transfer. RWD can be fun to slide around and throttle-steer on a snowy parking lot; but, out on the mean winter streets, FWD is much better for the great majority of people, I believe.

Edit is so convoluted…

Rider79. I grew up in the Midwest.

FWD is only better because of less torque. When the Cf is low, FWD or RWD matters little, but the control of RWD is superior.

The old FWD 4.9 Caddies were terrible in snow. Decent low end torque, what most would consider a lot, in a heavy FWD package. The 5.7 9C1 Caprice was WAY better in virtually every case.

Agree 100%.

Throttle oversteer is effective. And I nearly failed my drivers test doing just that in an ElCamino, in the snow.

Where does the FWD company in Clintonville, Wisconsin fit in? I visited the great museum in the former FWD/Seagrave plant there. In 1908 Otto Zachow and William Besserdich developed a mechanism to provide power to the front wheels. and produced the first successful FWD automobile that year. They supplied FWD transport trucks to the military in WWI. FWD bought Seagrave Corporation in 1963. Seagrave still manufactures fire trucks and other severe duty equipment.

It doesn’t. That company made four-wheel drive vehicles; not front-wheel drive vehicles. It was originally founded as the “Badger Four-Wheel Drive Company” in 1909. The “Badger” was dropped the following year. FWD was involved in some legal problems (as was Seagrave) and the assets were sold in 2003. Seagrave still exists, but is owned by a consortium affiliated with American LaFrance.

That was 4 wheel drive

I learned about a few fwd cars I did not know about or the stories behind them.

It should be pointed out that the photo of the Cord and Ruxton side-by-side seems to have the caption reversed. The Ruxton is clearly on the right.

That is correct, and I thank you for pointing that out.

Outstanding research, but it’s Leo *Goossen,* and what a genius he was.

Indeed it is, thank you for pointing that out.

Thank you for the correction.

I have owned several each of front and rear drive cars, the first front driver being an original Mini Cooper. I have driven both types on the street and on road racing courses.

The front drive cars can be as entertaining as rear drive – they just require a different technique. Front drive also has the advantage of being able to recover more easily from an oversteer slide by applying power to let the front wheels pull you out. As long as one does nothing erratic, the rears will follow the fronts. The cars can be made to oversteer by applying left foot braking or using the hand brake to lower rear wheel cornering traction.

One year in Michigan we were laying out an ice event on a frozen lake. The ice was clear of snow and smooth. We had a Corvette, an MGB, and my Mini. With the Corvette or the MGB, once a slide started you were just along for the ride as there was not enough traction for a recovery. With the Mini, one could get the car totally sideways and use the power to recover.

Different drivetrains, different techniques – both fun!

Owned a 67 Toronado for several years in Indiana, it would always win the drag race from stop lights on snow and ice covered streets and handled so well that you got a false sense of security that you would over drive your stopping distance.

Those Cord’s are stunning

Quite interesting. I always love to read that name “Archie Andrews”, as I used to often read “Archie” comics as a kid. (Betty or Veronica? Betty for me – and Mary Ann Summers – and Lana Lang).

There is a replica Fardier de Cugnot at the Tampa Bay Auto Museum, that was built to replace the one on loan from the Deutsche Bahn Museum in Nürnburg, Germany. Also, only two pics of Ruxtons?? Looks like you shot the one at the Tampa Bay Museum (brown one), but there is also a convertible coupe (lavender) at the Peterson.

If you look in the gallery, there are more photos of the Ruxton at the Eyes on Design show.

Been driving Citroen DSs since 1962 and still at it, but added a bunch of Panhards , which really started the volume and continuous production car industry in 1890. As Panhard Lavassor, the original co. name, built gasoline engines via a Daimler license they took in 1875, and the machine tools they manufactured for the woodworking industry gave them a strong foothold in general manufacturing, they combined a smaller version of their machine tool power engine with a platform built via their complete line of machine tools – including the first bandsaws, they put these two capabilities together and produced 26 cars 1890-91 to become the first production automobile company.

Best time I ever had in a FWD car occurred Feb 1967 in Evanston Ill. I was at Nweestern grad school with my ’59 Citroen ID19, with all of 70 hp, when on a Friday at noon, it started snowing. Snow ended noon Saturday, leaving 24 inches of snow over all of Chicago & burbs.

I cleaned the snow off the car, pumped up the hydropneumatic suspension, charged the snow with the car – whose powertrain was a true mid-engine – the transaxle being ahead of the engine – then dropped the suspension to pancake the 24 in. of snow. I pumped up the suspension repeatedly until i had made my own path out of that street to a main road which had been plowed. I never lifted one shovel full of snow – just used the car’s remarkable suspension to crush the stuff, and its FWD to pull the car thru the full 24 inches. Once out to a main road, I went around pulling V8s out of ditches and snowbanks – had a ball!

That Sat night I and two roommates drove the Citroen all the way from Evanston into the center of downtown Chicago, where absolutely Nothing was moving but us. No sweat at all – the car plowed its way thru every street with nary a hiccup. Back to Evanston after an evening of playing in the snow for the night – we never got stuck! THATS Traction.

Ken,

It’s so nice to see your name. I bet you have cars that even Myron Vernis doesn’t have.

To the other readers, Ken and I worked at the same DuPont automotive coatings laboratory for many years. I was just a lab tech and later an IT guy, but Ken is a brilliant chemical engineer. No job is perfect but it was nice to work with a lot of smart and creative people like him. One thing that I learned is that if you’re good at something, initials after your name don’t matter much. The first chemist I worked for was Eric Houze, who had a bachelor’s degree from a very small school. We shared a lab with Les Miller, who had gotten a degree from a mining school in Kansas but had done paint chemistry for four decades. I watched chemists and engineers with PhDs from impressive universities trod a path to consult with Eric and Les.

Glorious cars and great photos; like the ads too! But why did you show dePaolo at Indy driving what I think might be a Deusenberg which was decidedly rear-wheel drive?

As a mossback who learned to drive on front-engined rear-drive cars, I’m never completely at home with modern FWD: our newish Camry (the Japanese Buick?) has fairly neutral steering and handling, much ahead of our old Accord, but still has an ‘odd’ feel to me. Shows how any concept can be developed into something useful, though the ‘packaging’ issue was paramount for designers, nothing else.

But those Cords, Ruxtons, etc: I could spend a day just absorbing the bare chassis/drive-train details from the unbodied vehicles! And, there were a number of other American FWD’s too, in prototype. Amazing!

Ronnie Schreiber is to be commended for one of the most thorough, well-researched, accurate articles Hagerty has to date presented. Thank you for a concise look at this pair of early FWD cars and their background.

Thank you for the kind words. They are humbling.

The Bateman Company of Grenloch, NJ made the first front wheel drive car. The car now sits in the Harrahs Auto Museum in Lake Tahoe. They made the first front wheel drive truck as well. We have a picture of Henry Ford driving the car. The truck has not been located. My mother is a Bateman.