Media | Articles

How the Duesenberg brothers redefined the great American automobile

In California’s high desert, U.S. Route 395 meanders under the eastern shadow of the Sierra Nevada. Cruelly hot in summer and freezing in winter, it can also be windblown, sweeping Isetta-size tumbleweeds across the gritty terrain like demonic medicine balls. Or it can be benevolent, with only the caw of a wheeling crow and the distant drumming of tires rending the stillness. Nearby are an ancient lava flow, leering overhead like a battalion of case-hardened gargoyles, and several volcanic cones, their iron-rich alluvium spilling about like the train of hell’s wedding dress. And right beside the highway are scattered chunks of pure obsidian, gleaming black and smooth as a Duesenberg at Pebble Beach.

But what do volcanology and Duesenberg have in common? Insolent natural forces, and chance. The Earth’s surface was shaped by physics and time. And so was Duesenberg, which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2021. The “physics” that shaped America’s greatest luxury marque were the collective vision, drive, and innovation of Frederick and August Duesenberg—and, later, Errett L. Cord. The Duesenberg brothers were, figuratively, forces of nature in their time, developing and producing what some regard as America’s greatest cars, the 1928–37 Model J and supercharged Model SJ. Based on the brothers’ racing technology, they unequivocally delivered the most power, performance, and prestige at an unashamedly high price.

That is, until it all crashed and burned.

Two hundred miles south, the streets of Burbank, California, are the polar opposite of the high desert, with the maximum imaginable quotient of concrete and asphalt. Inside Jay Leno’s Big Dog Garage are eight Duesenbergs, including a supercharged 1932 Model SJ with a Murphy convertible body.

On a Tuesday morning last spring, Leno said, “If you’re going to write about Duesenbergs, you have to ride in one.” So I turned the passenger-side door handle, stepped in, and obediently sat, like a 5-year-old on the first day of kindergarten. There are no seatbelts. The engine-turned dashboard is crowded with instruments—including an altimeter, stopwatch, and brake-pressure gauge—plus four ingenious annunciators for chassis lubrication (every 80 miles), battery water level (every 1500 miles), engine oil service (every 700 miles), and the lubricant level in a chassis greasing system. Electromechanically operated, they are akin to an early computerized maintenance minder.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Leno was already inside, after unplugging a charger from the 6-volt batteries. With practiced precision, he set the ignition-timing lever and updraft carburetor’s choke, centered the gear lever, switched on the ignition, and pulled the starter knob. The big engine whirred slowly, laboriously turning its massive 350-pound crankshaft through 12 quarts of 50-weight oil and groaning like a massive radial on a Mitchell bomber. And then the 420-cubic-inch straight-eight engine sneezed, caught, and settled into a smooth, easy idle. Fred Duesenberg was passionate about engineering, and his engines prove it. The 3.5-foot-long forged-steel crankshaft has five main bearings and runs supremely smoothly, thanks to an integrated balancer incorporating cartridges filled with mercury—a liquid metal 13.5 times denser than water—that quell vibration. The forged camshafts are drilled hollow, and the aluminum pistons and tubular steel rods (Duralumin, or aluminum-copper alloy, on the Model J) are blueprinted.

The straight-eight drives through a three-speed non-synchro gearbox and a torque tube to the live rear axle. Though silky, the motor is busy-sounding, a telltale of the twin-cam cylinder head. The cams are driven by two chains; one from the crankshaft to a reduction sprocket on a jackshaft, and another, longer chain wrapping around the camshaft sprockets. Thirty-two tappets, located under polished aluminum covers, add more commotion. Add in the shaft-driven centrifugal blower and the deep, free-flowing exhausts (a cutout lever lets the driver bypass the muffler), and a Duesenberg SJ sounds like a machine shop in full production.

“Duesenbergs were bought by extroverts, Hollywood people, flashy people,” Leno said. “In 1928, there were hardly any roads you could go fast on, so there was really no need for a huge twin-cam four-valve straight-eight engine.” But the way you rose in stature in 1920s America was by flaunting it, and these were the fastest, most powerful you could buy. “Packard probably outsold Duesenberg 4 or 5 to 1,” continued Leno. “And because Packards were for bankers and conservative old money, you didn’t even hear them coming up the street. But a Duesenberg announced itself with the roar of the engine and all that kind of stuff. It was a showoff car, and certain people just loved it.”

Double-clutching between first and second gear, Leno guided the SJ out of the garage and toward the Golden State Freeway, accustomed to the stir that his impressive mug and such cars cause among Burbank’s populace. Although only a two-seater, the Murphy convertible is huge. Its 142.5-inch wheelbase is similar to a Ford F-150 SuperCab, and it weighs close to 6000 pounds. Mounted on 19-inch rims, its beaded tires stand nearly 3 feet tall—merely a hand’s width lower than the 1966 Le Mans–winning Ford GT40. With 6-inch-high sidewalls, the tires roll over city streets like an M4 Sherman tank over Rice Krispies.

Reportedly, the SJ could hit 90 mph in second gear, reach 100 mph from a standing start in 17 seconds, and go nearly 130 mph. “Imagine that in 1930, when going ‘a mile a minute’ was considered over the top,” Leno shouted above the engine noise. “This is a classic you can drive like a regular car, because it can keep up with traffic.” Then he punched it up the freeway on-ramp. The man gets on the gas.

***

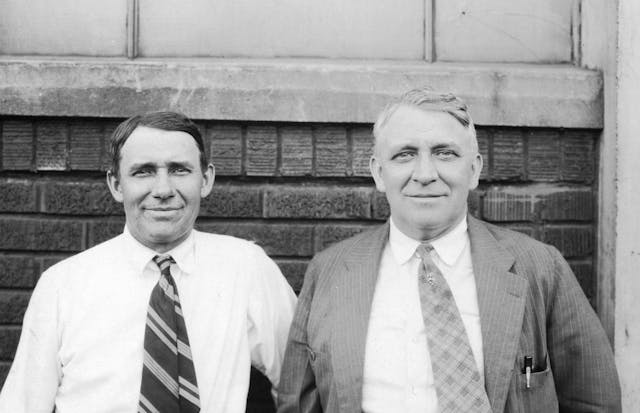

If you thought Duesenberg was a German car, well, it might have been. This constitutes the first bit of chance that let America birth Duesenberg for her own. Brothers Fred and Augie immigrated with their mother in 1885, settling in Iowa. In that agrarian state, they finished their formal education early. They were ambitious, though, and with Fred the hard-headed mechanical innovator and Augie the production specialist, they started building and racing bicycles.

Over time, Fred became chief engineer of Mason, an early car company based in Iowa, and with financial backing from founder Edward R. Mason, the brothers began developing four-cylinder race cars. They won several important races and finished 10th in the 1914 Indianapolis 500 with future World War I ace of aces Eddie Rickenbacker at the wheel. The brothers also began building truck and marine engines.

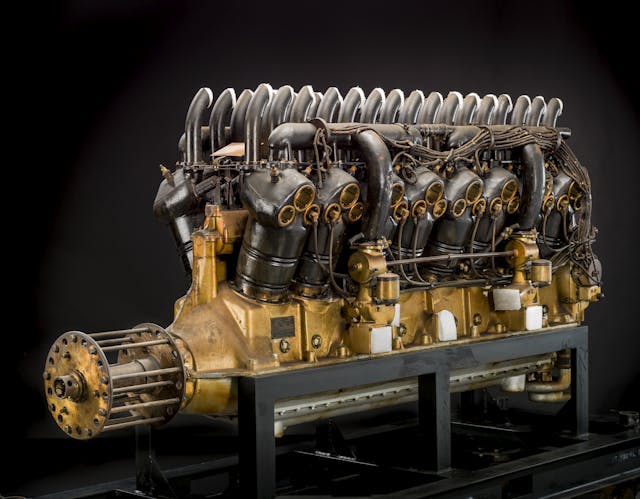

When Europe’s first war of the 20th century came pounding at America’s door, Fred Duesenberg was ineligible for active duty due to a leg injury from racing. So the brothers started manufacturing military aircraft engines in New Jersey. By chance, the Duesenbergs’ airplane unit was based on a powerful 16-cylinder Bugatti aero motor, created by pairing two straight-eights at the crankshafts in parallel to create a unique “U-16.” And since multicylinder airplane motors were more powerful, faster, and lighter for their size than car engines of the day, why not adopt their architecture? Motors made to kill might make killer car engines, too.

Wartime was hell for people but outstanding for technology. In the U.S. Army Air Service, a precursor to the Air Force, engines had to be light, high-revving, and powerful. This bred lighter valvetrains, aluminum pistons, higher crankshaft speeds, tougher bearings, and pressurized oiling systems. And so, while the Duesenbergs produced high-output inline engines for war, their interest in racing and Fred’s engineering acumen soon begat the Duesenberg straight-eight. By chance, the Duesenberg game board was set.

“Before the [Duesenberg] Model A was produced, they were looking at the market,” explained marque authority Randy Ema. “They followed the American Springfield-built Rolls-Royce concept, which was to build the chassis and engines and let coachbuilders create the bodies. One of their experiments was with early alloy pistons, an Achilles’ heel for automobiles. Production cars had cast-iron pistons and their engines operated at low speeds, up to maybe 1800 rpm. But eventually, the Duesenberg Model A could turn 4000 rpm and racing Duesenbergs could turn 5000 rpm.”

Soon after Armistice Day in 1918, the Duesenbergs focused on building a production car, the Model A. “They were already successful in racing,” Leno pointed out later. “They were like Ferrari—they liked to build racing cars. Well, how do you finance your race car wins? Build production cars and sell them.”

Their masterwork was the 260-cubic-inch, 88-hp engine, with its eight inline cylinders and gear-driven single-overhead camshaft, which made the Duesenberg Model A exotic for its day. America’s first such engine, its prescient layout became an essential part of production and racing cars, particularly at Indianapolis, until the mid-1950s. Cradling the motor was a ladder frame consisting of a pair of 8.5-inch rails made by Parish of New Jersey (later acquired by Dana Corp.), with six cross-braces. To these were bolted semi-elliptical leaf springs and solid axles, including a tubular front unit.

The Model A braking system was another Fred Duesenberg invention. He didn’t formalize the principles of fluid dynamics or make the discovery that fluids are noncompressible, but he did apply them to the Model A by using four-wheel hydraulic brakes with large, 15-inch drums. In lieu of brake fluid as we now know it, Duesenberg used a mixture of glycerin and water in the lines. And Fred never patented the invention. Imagine if he had.

Ironically, the racing- and aero-based engineering existed beneath typically unremarkable bodies. But to the Duesenberg brothers’ way of thinking, the whole idea was to achieve functional excellence, so letting owners and coachbuilders create the bodies was both logical and practical.

Some context may help here. In 1921, when the Duesenberg debuted, the automobile industry was transitioning from horse-and-buggy-era craftsmanship into mechanized moving assembly lines. Of course, Henry Ford, Walter P. Chrysler, and GM co-founder William Durant had head starts, but mass production simply wasn’t a mountain the Duesenbergs wanted to climb. Instead, every Duesenberg was hand-built from commissioned parts and assemblies at Duesenberg’s Building No. 1 at 1501 West Washington Street in Indianapolis. Part of the structure remains today.

With the engines and chassis done, bodies could be as elegant and rich as the buyer wanted. Coachbuilders including LaGrande (a Duesenberg holding in Indiana); Judkins Co. of Massachusetts; Brunn & Co., LeBaron, Rollston, and Willoughby Co. of New York; Derham Body Co. of Pennsylvania; and Bohman & Schwartz and Murphy of California created Duesenberg bodies. Fundamentally, period body designs needed to: a) cover the engine; and b) accommodate passengers. “You know, owners would sometimes put 10 people in their car—it was crazy,” Leno later said from a comfy couch in his “Brough Room” at the garage, named for the extensive collection of British Brough Superior motorcycles it holds. “So they just made the bodies as big and strong as they could. And particularly with the later Model J’s powerful engine, it worked fine.”

Want to know why a 2021 Mercedes-Benz S-Class looks the way it does? The dual necessities of covering the engine and accommodating passengers created the archetypical luxury look of a long hood joining a long body, which included a convenient side entrance we now simply call “doors.” And the forms stuck. Adding these requirements together, plus the period luxury element of a setback radiator, yielded two Model A wheelbase variants, one 134 inches and the other 141 inches. Long, sweeping fenders protected passengers from dust and mud on the primitive roads.

In 1921, the Model A chassis cost about $6500, with the coachbuilt body pushing the total price upward of $8500. For contrast, in 1921, Briggs & Stratton produced the Flyer, sort of a soapbox racer for the road, with two bucket seats and an air-cooled engine, advertised for $125. The wealth disparity of today recalls the wealth disparity a century ago. In all, 650 Duesenberg Model As were made.

***

Long before slogans such as “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” were bantered around conference rooms by marketing flacks, the Duesenberg brothers went racing. In contrast to Europe’s road races, in America, racing largely meant ovals, and so the two primary forms of motorsport already started diverging; the Indy 500 had only existed since 1911, and permanent road circuits didn’t exist at all yet.

This affects the Duesenberg story because oval racing and road racing required different approaches. The former rewarded durable high-speed engines, high-capacity oiling and fuel-delivery systems, high-speed tires, and reduced frontal area; it also required fewer speeds in the transmission. Conversely, road racing required flexible engines, multispeed transmissions, and strong brakes. The Duesenbergs’ interest and appetite for both forms of racing ultimately yielded a production car that was more fully rounded than those of its competitors, even though production Duesenbergs were not intended to be racers—just technically superior luxury cars.

Following their early U.S. efforts, including Indy, with four-cylinder single-seaters, the Duesenbergs went to Europe with bespoke 3.0-liter eight-cylinder racers. Their breakthrough was the French Grand Prix at Le Mans in 1921. An early form of today’s Circuit de la Sarthe, it then measured 10.7 miles and was rough as hell. To even call it tarmacadam would be a big stretch—during the 322-mile race, it grew rutted and the cars’ tires threw stones with punishing force. After battling the favored French Ballot entries, American Jimmy Murphy won by some 15 minutes despite losing his radiator water and driving the last lap with flat tires and a cooked engine. The Duesenberg racers were that strong. Importantly, it was the first time an American car and American driver had won a grand prix, a feat not repeated until Dan Gurney drove his Eagle Mk 1 to victory at Spa-Francorchamps in 1967. (Sadly, although the French GP–winning car returned to the States, where it continued racing with Miller power, it did not survive.)

Racers to the core, the Duesenbergs continued building engines and chassis for Indianapolis. In some form, their inventions raced at the Brickyard most years from 1913 to 1937 and won three times against their technological archrival, Miller, another dual-overhead-cam machine patterned after the Duesenberg. The Duesenbergs set land speed records as well, including a 1-hour run at Bonneville in 1935 at an average speed of 153.97 mph with a rebodied, supercharged Model SJ driven by Ab Jenkins.

***

The Model A clearly wasn’t for everyone, due to both size and cost, although these cars ultimately accounted for the majority of Duesenberg’s total production. Fiscally, this left Duesenberg on the ropes in 1926. Along came E.L. Cord, a captain of industry and the owner of Auburn, who had deep pockets and a flair for style. He visualized an even larger Duesenberg to headline a three-brand company that would include Auburn and, eventually, Cord.

Cord enacted his plan: Buy out Duesenberg Motors and provide the resources and freedom to build the most technologically advanced, the most powerful, and the most luxurious American car ever. This was, after all, the Roaring Twenties. And that’s what happened. From 1926 on, as chief engineer, Fred focused on creating the Duesenberg Model J, a machine that is still considered, nearly a century later, a pinnacle of American ingenuity, performance, and quality.

Rightfully confident with the cars’ engineering, their racing successes, and the infusion of cost-no-object capital from Cord, Fred Duesenberg embarked on building the finest motorcar the world had seen to date. Unsurprisingly, its essence was its engine. Debuting in late 1928, the Model J straight-eight was 420 cubic inches of dual-overhead-camshaft, 32-valve brashness. Valve actuation used a single cam lobe and follower for each of the valves, a dizzyingly complex arrangement for the day. Producing a reported 265 horsepower at 4250 rpm, the Model J engine was—by more than twice—the most powerful American production car engine. It was also the only DOHC eight-cylinder production car engine on the planet. Bugatti, Bentley, Hispano-Suiza, and Mercedes-Benz couldn’t touch a Duesenberg’s output, nor could any other American car until the Chrysler Hemi three decades later.

The Lycoming-built mill had European influence beyond Bugatti. In 1912, Peugeot, a maker of family cars, had created the world’s finest grand prix car using a DOHC hemi-head engine with four valves per cylinder, devised to reduce valve-train mass and thus valve float, a side effect of high revs that limited both engine speeds and volumetric efficiency. Swiss engineer Ernest Henry deserves credit here, but the Duesenbergs saw the value and first harnessed it in a production car. It’s worth noting that over a half-century later, Mercedes-Benz in 1986 and Oldsmobile in 1988, with much fanfare, announced their four-valve engines, the 190E 2.3-16 and Quad 4, respectively. Now they are commonplace in most every variety of automobile except those with pushrod valvetrains.

Duesenberg’s sophistication came at a price, however, because (for example) a Model J valve adjustment requires both camshafts come out and it consumes an entire 40-hour workweek. “But Duesenberg said, ‘We don’t care what it costs,’” Leno said, shoes propped on a coffee table and gazing at a Brough SS100 worth maybe half a million. “‘We’re going to have four valves, twin cams, and perfect balance.’ It was just ridiculously amazing. To me, the two greatest [cars] are the four-valve 8-liter Bentley—although it was only a six-cylinder—and the 7-liter Duesenberg. And by the way, compared with the Model J, I think the Mercedes 540K drives like a truck.”

Ema added later, “I personally have driven everything, including the Bugatti Royale, Hispano-Suiza J12, and Bentleys. None are as drivable as a Duesenberg. Even comparing apples to apples, at the time, a Rolls was more money and a fifth the car, with less than half the drivability. The Rolls turned 2100–2200 rpm max, and in terms of power, in 1928, the closest American car was a 115-hp Auburn Model 115 flathead-eight. Nobody had anything close to the Model J. The Duesenberg was a Veyron compared to a Fiesta.”

The Model J “chassis,” as the rolling machine was called, still used a ladder frame, with elliptical springs and Columbia axles that were stiffer than those of the Model A. The wheelbase options were 142.5 inches or 153.5 inches. Innovations included lightweight aluminum castings for the firewall, the instrument panel, and for its hollow mounting brackets. It was an elegant contrast to other luxury cars that used sheet metal in these places. Up front, in lieu of a thermostat to control water temperature through flow restriction, automatic radiator shutters opened and closed as the cooling needs dictated. A bimetal spring inside the radiator tank moved a bell-crank to open the shutters as water temperature rose or close them as it cooled. This was in 1928; Honda ballyhooed its own active shutter grille 90 years later.

There’s more: As an early form of antilock brakes, the Model J had an adjustable valve that increased or lessened vacuum in the brake booster. In ideal road conditions, the driver opened the valve fully, thereby allowing maximum hydraulic pressure during pedal activation. The valve could be adjusted for rain and snow, reducing clamping force at the drums to lessen the likelihood of wheel lockup in low-grip conditions. A gauge displayed hydraulic pressure on the instrument panel. Note: Electronic ABS finally gained prominence in production automobiles in the 1990s.

With Cord’s blessing, the Duesenbergs maintained their focus on building the best possible “chassis” while entrusting coachbuilders to finish the car. Both American and European coachbuilders were used, per Model J buyers’ preferences.

Prior to delivery by driving, truck, or rail, every chassis was driven several miles to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and tested for 100 miles, with each driver responsible for sorting out any problems found. Exactly 481 Model J chassis were built, at a nominal cost of $8500. A done-to-the-nines Model J could cost $25,000 at a time “when a house cost $1200,” noted Leno.

***

Like a town built unknowingly on a giant strike-slip fault, Duesenberg’s undeserved misfortune was that it began producing America’s grandest car right before the Great Depression of 1929 knocked the country flat. Worse, this happened when the company was having its biggest year (200 cars sold), employing 42 people (at a typical wage of 50 cents per hour) and turning out a chassis every 22 days. The Depression, predictably and historically, ended Duesenberg Inc. in 1937, but not before the untimely demise of Fred Duesenberg, who succumbed to pneumonia in 1932 after suffering injuries in a road accident. Duesenberg had lost its engineering seer, its magma source, its soul.

Included in the Model J build were 38 supercharged Model SJs, whose chassis were priced at $9500. A shaft-driven centrifugal supercharger turning at seven times engine speed—up to 31,500 rpm—pushed a dense, powerful air-fuel mixture into the cylinders. Bolstered by their tubular-steel connecting rods, SJ engines produced a claimed 320 horsepower at 4200 rpm, enough to propel the 3-ton cars to 140 mph. But it takes a big commitment with the right pedal to make this happen; the supercharger is ineffective below 2500 rpm, about where the SJ cruises at 65 mph. Like in a race car, in a Duesenberg SJ, you must step on it if you want to go.

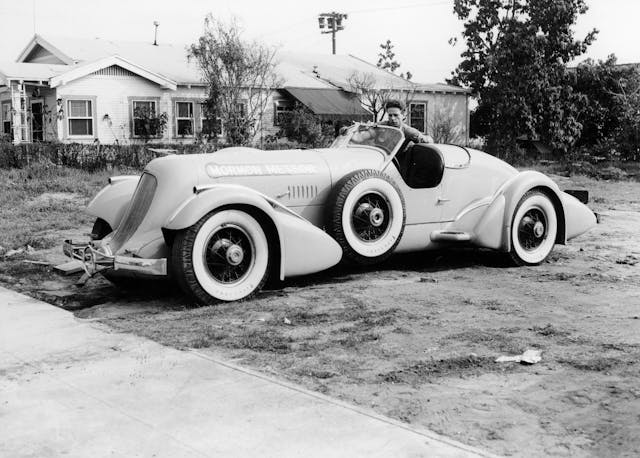

The iconic side exhausts, initially an SJ exclusive, were adopted for their flash appearance on numerous normally aspirated Model J cars. Two special, shorter, 125-inch-wheelbase two-seat roadsters were delivered to actors Gary Cooper and Clark Gable. They featured twin updraft carbs and reportedly made 400 horses, slightly shy of the audacious 1967 Corvette L88’s rated 430 horsepower.

***

Richie Clyne and Sam Mann are friends and collectors who own seven Duesenbergs and actually use them on tour. “I have driven my 1933 Murphy Town Car all over the country,” Clyne said. “If you’re standing still in traffic or parking, it’s hard to turn, but on the open road at 70, there’s a wonderful sweet spot where the engine torque, gearing, steering, ride compliance, noise, and vibration are all in harmony.”

“I organize an all-Duesenberg tour where we drive 200 to 250 miles a day for four straight days,” Mann added. “If you are going to do twisties and drive fast, your technique needs some maturity and it’s a little tiring, but I would say no more so than driving a 300SL.” But once you’re familiar with the car on halfway decent roads, it’s very much a serene experience, he added. “They’re not like a needy World War I–era car to keep running—they just need gas.”

In a final bit of chance, Augie Duesenberg died in 1955, the year Chrysler’s C-300 broke the 1928 Model J’s 265-hp figure with a dual-quad 331-cube Hemi. The great book had closed. As automobiles evolved and WWII came and went, Duesenbergs met with mixed fates. Some stayed with their families for generations, while others were summarily scrapped, or in the case involving Leno’s incomparable aerodynamic Walker Coupe, used as a tow truck. “During World War II, a Duesenberg might be found for $600,” said Leno. “If that sounds cheap, consider that, at the same time, a used Ford Model A cost $5. So they’ve always been expensive.”

Today, 378 Duesenbergs Model Js are known to exist, and Ema has seen all but a few. As for value, the SSJ owned by Cooper and later Briggs Cunningham sold for $22 million in 2018, making it the most valuable known American car. On the low end, a decent “starter” Duesenberg Model A might run $300,000 today. Author Ken Purdy couldn’t have predicted such values in his 1960 book, Wonderful World of the Automobile.

“Many Americans have never seen a Duesenberg automobile, the most luxurious and expensive this country has known,” he wrote. “Today the cars rarely come on the market at all and when they do the price asked ranges from $3500 to $10,000 … it’s unlikely that we will ever build $25,000 cars again.”

The numbers may have changed with inflation, but the sentiment is correct: Duesenberg will likely never be topped as America’s greatest force of nature in the art of the automobile.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

I was lucky enough to ride in a Duesenberg. A black roadster was shipped to my mechanic the late, great Mark Lambert here in Nashville to prep for the Pebble Beach Concours. After he finished it was shipped to California. He dropped by my little house in it one night and took me for a spin for a few blocks. Can’t believe there was a car like that in my driveway. This was in 2011. Remember all the gauges and how tight the seating was for two guys. I actually got to go to that show that year. The work Mark did for me was rather plebeian as my old cars are a ’48 Chrysler Windsor club coupe and a ’54 Chrysler Windsor sedan. Mark was a judge that year at Pebble. He was a wonderful man. I am sure some of you on here either knew him or knew of him.

That was an Outstanding article John !!

I commend you on all the time , effort and research you put into it and I thoroughly enjoyed it and the pictures were just amazing to say the least.

Nice job, I’ll be saving this one for future reference as the persons collection I take care of , is considering one for his collection.

Great article. Well done!

Actually Fred Duesenberg did patent the hydraulic brakes used on the Model A Duesenberg. It is #1,603,668 issued 10/19/1926. He actually received several patents besides the hydraulic brakes.

Saw Lee Anderson’s 2022 Pebble Beach Best of Show winner & his 8 others at his museum in Minnesota this past September. Absolutely incredible!! All of his Deuseys & the rest of his amazing collection was a car enthusiasts dream!