Media | Articles

How the child car seat went from deadly novelty to lifesaver

If you drive and have children in your life, you probably own some kind of car seat for carrying the little dears. Where to put the kids while driving has been an issue since the earliest automobiles. In 1906, the Waltham Mfg. Co. of Waltham, Massachusetts offered a “Detachable Child’s Seat” as a $25 option on its $425 Orient Motor Buckboard. As you can see from the advertisement, that seat was detachable and fitted to the very front of the vehicle. Great for visibility, not so great in a collision.

Today’s kids benefit from racing-seat levels of protection: federally mandated seat anchors, five-point harnesses, and side bolsters by their heads, to minimize neck movement and help avoid injury to developing spinal columns. It is thus tempting to say that in the early days of the automobile, safety was viewed as optional convenience. Parents mostly wanted to keep their children in one place in the car.

Still, there was a need, and aftermarket companies did use safety as a selling point. And so we have things like the Lull-A-Baby Car Hammock, the “safest, most comfortable car bed ever made,” and the Gordon Motor Crib, “The Safest Way, the doctors say.” While it’s easy to laugh at pitching like this, context helps: The Motor Crib’s ad copy boasted “no more weary arms” for driving mothers. The alternative, in other words, was Mom operating a 1920s automobile while holding an infant.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

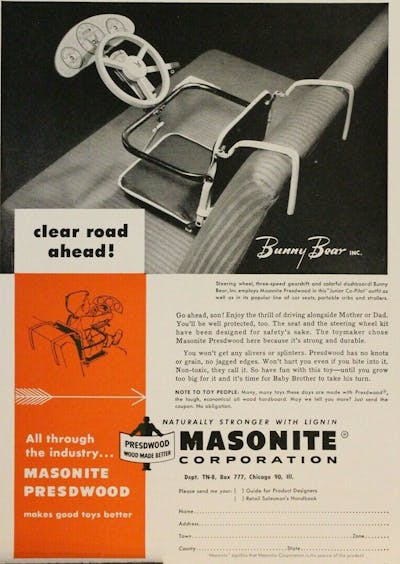

While the Waltham seat was a factory option, child car seats were typically not offered by car companies for much of the 20th century. Instead, they were sold by outside firms, like manufacturers of furniture and strollers. The earliest child seats were simple affairs, a fabric seat like you’d find in a swing set, often suspended from the rear of an adult seat by drawstring or metal hooks. In 1933, the Bunny Bear Company introduced a folding metal car seat that pretty much set the mold until the 1960s. While the Bunny Bear seat carried a rudimentary, three-point lap belt, there was no way to secure the seat in place—it looked as if it would literally just fold up during a collision.

Bunny Bear’s products did eventually adopt securing hooks, but safety remained an afterthought. Sometime in the 1950s or early 1960s, someone at the company must have realized that looking out the window might get boring: The Bunny Bear seat gained a toy dashboard, complete with steering wheel, shifter, and instruments.

Understand that while parents have always been concerned with child safety, consumers in general have not always been that safety-conscious. Ford first offered seat belts in 1956. General Motors and Ford both offered air bags more than 50 years ago. In each of those cases the “take rate”—the percentage of customers that chose to purchase those options—was so low that those features were discontinued.

Finally, in the early Sixties, a couple of inventors got serious about making it safer for children to travel in cars. In 1962, British journalist and mother Jean Ames designed a rear-facing child seat with a three point Y-belt for restraint. Three years later, she patented a five-strap harness with a quick-release pin and licensed it to the D.C. Morley Engineering company. Morley then marketed “The World’s FIRST Car Safety Seat for young children,” the Jeenay.

Convenience was still a factor, and the Jeenay’s ability to be double as a household high chair was a strong selling point. Today, it is illegal in many jurisdictions to carry a child in the front seat of a car; it is demonstrably safer for small children to ride in the rear seat. Sixty years ago, the Jeenay was advertised as being “anchored in the rear seat safety zone.”

In the late 1950s, Leonard Rivkin and his wife Reva owned a children’s furniture store in Colorado. When their car was struck from behind in an accident, their son Bart was launched out of the back seat and into the front of the car, where he landed at his mother’s feet, uninjured. Leonard had a background in civil engineering, and his son’s close call inspired him to design and patent a booster seat with a strong steel frame and a five-point harness. Rivkin later adapted the design to fit between a pair of bucket seats. After a brief stint manufacturing his seat with a business partner, Rivkin licensed the design to the Strolee stroller company, which sold it for more than a decade.

In 1964, Professor Bertil Aldman at Chalmers University in Sweden (home country of Volvo, where Nils Bohlin invented the three-point adult safety harness) was watching an American TV program about the U.S. space effort. He noticed that the astronauts in the Gemini capsule were lying on their backs during launch—this position allowed their bodies to better withstand the forces of a rocket’s acceleration. Aldman applied the principle to head-on collisions, suggesting that child car seats should face backwards. In this way, a child’s neck wouldn’t bend forward relative to his or her body during an accident, and force would spread evenly across the back and spine. Further research showed that the design also offered protection from side impacts.

Although evidence strongly indicated Aldman was right, it took him and researcher Thomas Turbell some time to convince people that a rear-facing child wouldn’t immediately suffer motion sickness. Sweden eventually instituted child-car-seat standards that made it difficult for forward-facing seats to become legal.

Where independent inventors showed the way, automakers followed. Ford came first in 1968 with the Tot-Guard, a forward-facing seat with a padded restraint. GM followed with the Love Seat for Toddlers, a more conventional forward-facer with straps, and then the GM Infant Love Seat, a rear-facing bucket design that carried my first child home from the hospital. Convenience was still a selling point, as GM offered an optional frame that turned the Infant Love Seat into a stroller. Both GM and Ford’s seats were secured with the car’s seat belt or a three-point harness.

Finally, in 1971, the government got involved. The Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards for that year carried regulations concerning child car seats. While crash-testing was not a requirement, those seats did have to be anchored into the car with the vehicle’s safety belts, and the seat had to have its own restraints for the child.

In 1979, Tennessee enacted the first American child-restraint law. The other 49 states quickly followed, and by 1985, car seats were mandatory across the nation. By the late 1990s, automakers had introduced LATCH (lower anchors tether children), a standardized and locking engagement system for attaching child seats to a car’s seat; federal regulations enacted in 2003 required automakers to equip new vehicles with child-seat lower anchors and top tether points. Child seats from companies like Graco, Evenflo, and Fisher Price are now larger and safer than ever, and competition in the market is driven by features offering genuine protection for our kids.

Car seats have come a long way in the last century. These days, it’s not unheard of for kids to walk away from collisions that leave adults in the same car seriously injured or dead. However, it’s important to note that child car seats only protect your children when they are used correctly. That process begins before you buy or borrow a child car seat. It’s important to ensure that you’re using the correct seat for your child’s height and weight, and to recognize that, as the child grows, they will grow out of that seat and into another, until they are big enough to use only the vehicle’s standard seats and three-point belts.

Like racing helmets and other safety gear, child seats can also have expiration dates, driven by material fatigue and predicted abuse. Note those when you acquire a seat, and make sure to dispose of the seat when it’s past due. Finally, no safety device can work if it isn’t used. Recent data shows that more than half of the children under 15 who die in modern car accidents do so while completely unrestrained.

Please, when you travel with children, put them in appropriate child car seats, and use those seats correctly.