Media | Articles

How the 1955–57 “Tri-Five” Chevy became a midcentury masterpiece

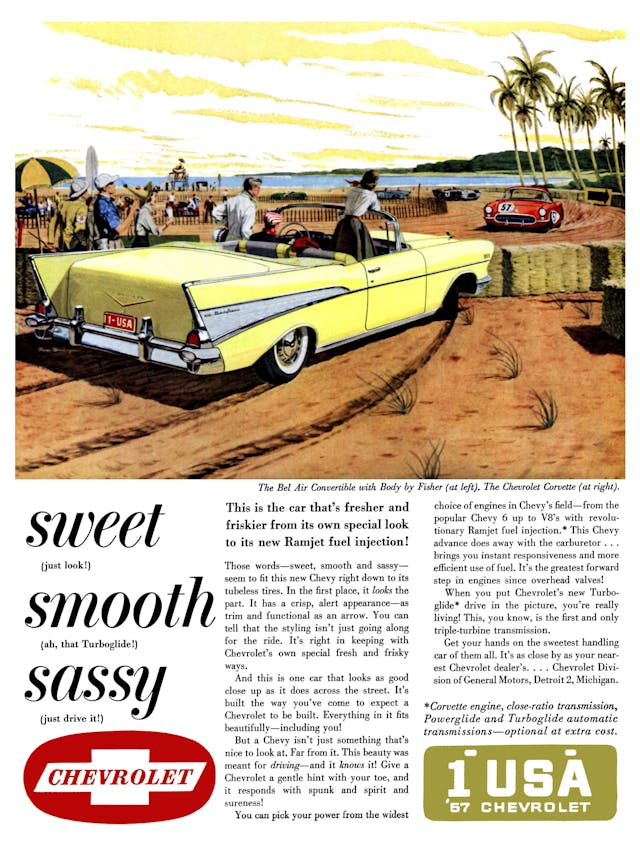

As companions to Aaron’s lovely historical feature below, we are publishing three Hagerty member stories about their own Tri-Fives. You can read the first installment, about a green 1955 Nomad ex-drag car, here. The second installment, about a 1957 Bel Air convertible dream car, lives here. And lastly, our final installment about Betsy, a tattoo artist’s 1956 Chevy Bel Air Sport Sedan, here. –EW

It’s strange to start a story about some of the greatest General Motors cars ever produced with a nod to Henry Ford. But that’s where it begins, with the famous founder’s resignation in 1945 and the handing of the company keys to his 28-year-old grandson, Henry Ford II. From his perch atop his mighty arsenal of American industry, the young Deuce could see an even taller mountain just to the east, and it had a chrome bowtie on it. Ford knew what he had to do. “Here’s the car that will lead the way,” ran a subsequent Ford advertising ditty, “and beat the hell out of Chevrolet.”

Well, there were 90,000 people working for Chevrolet in the early 1950s, headed by the likes of general manager Thomas H. Keating and chief engineer Ed Cole. They weren’t going to simply roll over while Ford ate their lunch. Competition spurs innovation, and when the wraps came off the 1955 Chevrolets, the Deuce must have known that he was in a fight. Chevy showed that it was quitting the business of selling plump little economy sedans for the old folks. The ’55s were trim and direct, with a Ferrari-inspired grille, a Corvette-influenced dash, a rakish two-tone color scheme, and a new V-8 if you wanted it. The chrome and other tick-tackery were kept to a minimum—the jet taking flight on the hood notwithstanding—and the car’s bluff body lines were left to stand on their own.

Somehow, in one car, Chevy captured the boundless optimism of a nation whose youthful population was growing by 11,000 souls a day while also embodying John Wayne’s maxim to “talk low, talk slow, and don’t say too much.” The rest, as they say, is history. The 1955, 1956, and 1957 Chevys sold in the millions and became the holy Tri-Five, the beloved Shoebox Chevys (because of their boxy profile), the three cars that for a graying generation today best represent the decade of the 1950s and all their fond memories of youth, freedom, rock-and-roll, horsepower, and a prosperous suburban America at peace.

For the rest of us, the Tri-Fives, a nickname invented in later years to encompass the ’55s, ’56es, and ’57s, are simply cool, sized and styled just right and in a way that transcended the era of excess into which they were born. Today, a ’55 Plymouth is delightful; a ’55 Chevy is a national monument. Drive one through Brooklyn, Highland Park, North Kansas City, or Compton and people will flash you a thumbs up. Ford sure tried, but it couldn’t bump off the bowtie as the most American of American brands.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Tri-Five’s genesis started when Ed Cole kicked the door in at the sleepy Chevrolet Division in May 1952. Demanding and energetic, Cole had led the development of the 1949 overhead-valve V-8 at Cadillac before going off to a GM defense plant in Cleveland to run tank production for the duration of the Korean War. He arrived at Chevrolet already determined to invigorate its fusty image, with the Corvette planned for 1953 and a cut-price V-8 coming to finally answer Ford’s decadelong lead in that department. Chevy wanted younger buyers, and the youth wanted horsepower. GM had earmarked $300 million for Chevy’s 1955 model overhaul, and Cole was determined to spend all of it.

He went on a recruitment drive, luring young engineers with the tantalizing prospect of reinventing Chevrolet with bold, exuberant products aimed at performance. Then he flushed whatever the division had already been working on, shelving a V-8 project based on the expensive and heavy Cadillac motor and tasking his staff with developing an engine that was smaller, lighter, cheaper to make, but still powerful. Precision thin-wall casting and stamped rocker arms were some of the enabling technologies for a compact new 265-cubic-inch “small-block” V-8 that would launch a dynasty, the descendants of which are still in production today.

Wisely, Cole nurtured his relationship with GM’s autocratic styling chief, Harley Earl. Thus, unlike other divisional chief engineers, he was not an unwelcome visitor to the styling studio on West Milwaukee Avenue, behind the GM headquarters building in Detroit. There, through the summer of 1952 and into 1953, the ’55 Chevys emerged from sketches and clay lumps under the guidance of the division’s styling head, Clare “Mac” MacKichan.

“We were working on front ends in the studio in the early stages, and one day Harley came in and said, ‘You know, I saw a Ferrari, and I’d like to try that kind of grille on the car,’” MacKichan recalled to author Michael Lamm in 1975 for Lamm’s subsequent book, Chevrolet 1955: Creating the Original. “And then he described what he wanted and, of course, we got out magazines and pictures and started to do this grille.”

On Milwaukee Avenue, they were aiming high, trying to produce a mini-Cadillac at a Chevrolet price. Hooded headlights and frenched-in taillights that recalled a lady’s elegantly enameled fingernail were prominent Cadillac riffs. As a flourish and to accentuate the rear haunches, the designers pressed a dip into the horizontal beltline just aft of the B-pillar and accented it with a chrome band that joined to a side spear. These ornaments formed a natural border for one of the ’55’s signature elements, a white accent color on the top trim level that wrapped over the trunk and onto the opposite quarter panel.

“The Hot One,” as Chevy marketers called it, debuted officially when dealers peeled the paper off their showroom windows on Thursday, October 28, 1954. The public pressed in to see the new car—and it was indeed totally new. Of the roughly 4500 parts that went into a 1955 Chevrolet, boasted Keating, Chevy’s general manager, fewer than 700 were carryover from the previous year. Including the switch to a 12-volt electrical system, the changes, crowed the former car salesman with perhaps understandable hyperbole, “were greater than have ever been attempted by an automobile manufacturer in one year.”

The new 162-hp Turbo-Fire V-8—or 180-hp with the optional four-barrel carb and dual-exhaust “power pack”—was said to benefit from “dynamic engine balancing” that involved spinning each engine to 700 rpm and using an “electronic brain” to measure and counterweight out any wiggle in the crankshaft. Other robotic machines were used to perfectly broach, plane, and mill the 190-pound castings of the V-8 block. For the first time, overdrive was an option on a Chevy, though priced at a steep $108.

There were three models—the base 150, the mid-priced 210, and the deluxe Bel Air—encompassing 16 separate body styles. Earl wanted to offer something special for the ’55 Chevys, so in 1953, he commanded his team to sketch a two-door wagon that used the upper half of the forthcoming 1954 Corvette Nomad show car and the bottom half of the ’55 lineup. Station wagons were red-hot sellers at the height of the baby boom, by which time 35 million Americans were said to have moved out to the suburbs. The Chevrolet Division built 160,000 wagons in 1955, the Nomad (as well as the lesser 150 and 210 versions, which weren’t called Nomads) being one of two wagon bodies offered that year. The two-door wagon claimed a healthy 54,000 sales in ’55.

However, sales were halting at first; the public took time to warm up to Chevy’s pivot. During the first two weeks, weeds grew at the dealerships, and GM president Harlow Curtice called a meeting of Keating, Cole, and other managers. Curtice arbitrarily pinned the problem on the grille, saying that Ferraris sold in the hundreds while Chevy was gunning for millions. The group sketched out a rush program to redesign the grille, but before it could be implemented, dealers began to see some traffic (the replacement grille concept was adopted on the ’56 models).

Perennial Chevrolet pitchwoman Dinah Shore rode the back of a Bel Air convertible to pace the 1955 Indy 500, while drivers Fonty Flock and Dave Hirschfield campaigned the new car in NASCAR’s various series. Kustom king George Barris wasted no time applying his touch, restyling a ’55 Chevy with Dodge trim pieces, Lincoln taillights, and a Corvette grille. Said Chevy designer Dave Holls: “If there was ever a time when the kids went 360 degrees from Fords to Chevys, it was 1955.”

By the spring of 1955, the cars were flying off lots. On April 28, a Thursday, the Chevrolet Division set a one-day industry production record, cranking out 7902 cars and 2178 trucks before the evening whistle. In announcing the record, Keating reeled off some statistics: the $20 million worth of vehicles produced by Chevy in one day would, if parked end to end, stretch 35 miles. The 33 million pounds of steel needed to make those vehicles had employed 20,000 steelworkers and was enough metal to erect a skyscraper with a base of one whole city block and a height of 25 stories. Altogether, Chevy’s plants and their suppliers had consumed 50,400 tires on that Thursday, 1.7 million pounds of paint and other chemicals, 7 million pounds of iron, 27 million gallons of water, and 650 tons of coal, while producing enough textiles to wrap around the globe four times.

Such was the postwar industrial colossus that was Detroit, the city’s Big Three (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) owned 95 percent of the U.S. auto market in 1955. Chevrolet handily beat Ford that year, as it did in 1956 when it softened the car’s look slightly and applied the ’55’s wider replacement grille. Always a fan of chrome, Earl pressed his underlings to gussy up the now spectacularly successful Chevy line for 1957. The result was an even larger and busier oval grille bracketed by prominent bullets and bisected by a chrome center bar housing inset parking lights. The flat hood sprouted two long bulges capped by chrome rockets jutting forward, and the treatments got more deluxe as buyers moved up the line. Flashy dorsal-shaped side molding inserts for Bel Airs accentuated the new tailfins.

Though it’s revered today, the ’57s proved less popular with the public then, and Ford regained the sales crown by about 30,000 registrations. Some economists blamed the fierce battle between Chevy and Ford, with all the attendant discounts, rebates, and overproduction, for sparking the 1958 recession. It was said that pie-in-the-sky sales targets involved shoving cars on to people who couldn’t afford them (auto loan defaults climbed dramatically in 1958) while driving the few remaining independents, Nash-Hudson, Studebaker, and Packard, to the brink of bankruptcy.

Whether true or not, Ford and Chevy continued their sales war, the latter largely abandoning vertical tailfins after ’57, flopping them over into horizontal blades before pruning them off entirely for 1961. The completely redesigned ’58 Chevys followed the industry trend toward longer and wider cars with even more chrome, and the all-too-brief Tri-Five era was over.

Except that it wasn’t. The Chevys from those three years took less time than most models to rebound from depreciating used cars into desirable classics. There’s always been something appealing about a big engine dropped into a cheap car, and the ’55 Chevy with its compact new V-8 was destined to rank with the ’32 Ford as the roots of America’s muscle car epoch.

GM turned against racing, starting with a 1957 ban by the Automobile Manufacturers Association and reinforced in 1963 by a company fearful of breakup by antitrust crusaders. That meant the Tri-Fives would represent at the drag strips in later years as the car of the grassroots independents and the little guy. Into the mid-’60s, small-block tuning pioneers such as Bill “Grumpy” Jenkins and his Monster Mash ’55 Chevy were cheered as underdogs against the newer factory jobs. Meanwhile, the Chevy Nomad seemed built to specification for the 1960s surf craze set to an epic soundtrack by The Beach Boys, Jan and Dean, and Dick Dale & His Del-Tones.

Early on the Tri-Five was a screen regular, starting with Rebel Without a Cause and the Highway Patrol TV show. Star turns in Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), American Graffiti (1973), and Diner (1982) kept the Tri-Fives in the public’s eye as the most 1950s of 1950s Americana. Go online today and you can buy Tri-Five metal signs, Tri-Five models, Tri-Five T-shirts, Tri-Five–only magazines, and couches made to look like the rear end of a Tri-Five Chevy. Those three model years support an enormous aftermarket parts industry that supplies everything to keep a Shoebox Chevy running, up to and including completely new steel body shells officially licensed by Chevrolet.

Which is why if you go to any car show, concours, cars and coffee, or cruise-in anywhere in America (and likely elsewhere), you’re all but certain to see at least one 1955–1957 Chevrolet. More than 3000 show up every year to the Tri-Five Nationals hosted by the American Tri-Five Association, whose members are certain to write in and point out with exhaustive detail any mistakes in this story.

A story which, at its heart, is about a commercial product. It was developed and built for the purposes of turning a profit over three short fiscal years in the life of a corporation that, once those years were over, quickly moved on to other matters. Car designers and engineers usually don’t know when they’re being timeless—not until some time has passed. They also don’t get to pick which of their creations qualifies; that’s for the rest of us to decide. And in the intervening years, the masses have spoken, blessing the Tri-Five with its well-earned immortality.

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

I’m fortunate enough to own a 57 nomad all original which i purchased from the second owner in 2019 with only 58k on it. runs and drives great. I don’t think we’ll ever see automotive fashion like that again.

To me – the 1955 Bel Air and Nomad were the best designs of the so called “Tri Five” Chevys…1956 the least attractive with its “change for change’s sake” squared-off headlight bezels and ugly tail lights that looked unfinished. The 1957 had too much glitz on it – and it was the 3rd year of a boxy, upright body style, while the Fairlane series of Ford and the Plymouth line were all-new longer, lower, wider cars that instantly made the 1957 Chevy look antiquated. While 1957 Chevy sales decreased compared to 1956, Ford sales and Plymouth sales both increased significantly…Ford beating Chevy for the 1957 model year sales crown. As for the article – which was also the magazine cover story – great pics, but the collector car hobby does NOT need another cover story on Tri-Five Chevys…boring – Haggerty editors are better than that – and could cover something more interesting – maybe 1957 Fords and Plymouths would be a good starting place!

The fame of the Trifive’s will soon completely die out, as will its baby boomer owners as myself.

By the time the Z generation decides to get a classic, the trifives will be over 100 years old. Anyhow, these cars will be restricted to garages like all the classic cars. You won’t be able to get it licensed. Everything will be electric. The kids will say, what’s an internal combustion engine.

I do like the Tri-5s, but for pure inspired design beauty, the ‘53-‘56 Studebaker Starliner coupe designed by Bob Bourke was the winner. The “Lowey Coupe” made everything else on the road look old.

The tri-fives are very attractive – and will be thought of that way for a long time. BUT they are NOT “timeless”. They are very much product designs of their own time. They are popular, good-looking icons of ’50s styling. But they will likely never be mistaken for being produced in another decade.

The Studebaker Loewy coupes (especially the ’53s and ’54s) were more what may be called timeless. They were so far ahead of the rest of the industry that they still looked beautifully styled next to most cars of the whole ’60s decade too. A lot of automotive stylists would likely agree.

In 1955 I was just married and had my first full time job. I took a bus to work. When I got off I walked through the plant parking lot. There it was a 1955 Chevrolet. I was struck by a bolt of lightening !!! All these years later, that sight is still burned in my brain. ………..Jim.

Chevrolet’s were marketed as economical transportation out selling the competition for 25 years prior to 1955. The 567’s just more of the same. Ford won the sales race now and again 1930,35 and 57 always a close battle.

My family had smooth body 49 and 51 Fords then my dad pulls in with a 53 Chevy. My mother hated it with it’s 1940’s big humped back rear fenders where as since 49 Fords we’re already streamlined. It took GM 7 years to get with it! Lucky for us he replaced it with a 57 Chevy (my mother went shopping with him for that one haha)

My parents had both a 55 Chevy 2 door wagon and a 57 chevy 4 door wagon. Both were the 210 series, but they were interesting. Used for their drapery business. My neighbor Cora sold her 52 Packard and bought a first year 210 4 door hardtop, in two tone red & white. With a PG and a 265 V8 2bbl it was a nice car. She made wedding cakes and my brother, and I would help her put those cakes in the trunk.

My first car was a beater 54 Bel Air post. It went thru a brick wall at a transmission shop, so I needed another car. It was November and my Yamaha was getting too cold to ride every day. I towed the 54 back to my house, put signs up at high school for parts. soon, those parts made the 54 a skeleton and I sold it for scrap.

Cora had just bought a 65 Buick and the 210 was for sale. for me, she said, $500, pay me when you can! I sold the Yamaha and paid her off with the scrap money and had George Reimche make that 265 a 283 with solids and a Duntov cam.

I wish I wasn’t so smitten some months later when I saw a 64 Elky at a dealer. The car eventually returned to my street with a neighbor kid buying from Cora’s husband who got it from a crooked dealer that turned the odometer back 30K.

I now own a 56 four door hardtop with a continental kit, skirts and visor but I have improved it with disc brakes, new smoked windows and custom seats with power windows. I have a Chevy addiction of pickups and a Chevelle SS to relive that 64 Elky only much tamer and Retromodded.

Though so many prefer the 2 door hardtops, I like the lesser is more tastes of the 2 door posts and 4 door hardtops 210 that have so much more subtle chrome trim.

If you are fortunate to find a copy of Rodding and Re-Styling magazine (November 1959) take a look at the most beautiful customized 1957 Bel Air convertible on the planet, both then and arguably now. I was privileged to know the history behind this car and had several opportunities to drive it. George Barris, custom car builder smiled greatly when he saw it at major car shows back then. And yes, it was a driver!!

Absolutely great cars with timeless legendary styling in the heyday of the all-American mid 20th century. I was only seven years old when the 55 Chevy came out. Every kid on the block of my Northeastern Ohio hometown had that envious look in their eyes……Someday!!!

WOW, what a great article to bring back memories to this 74 Corvette Stingray owner, always a “Bowtie” man!!!

My dad traded-in his stick shift 6 cylinder 1952 chevrolet for the foot longer, lower, wider, bigger, forward looking gently shaped 55 Plymouth …in two tone cream over turquoise with the Plymouth version hemi v8 with the Powerflite automatic and power steering. Great ride. Mom said easy to drive. Neighbor bought a 56 chevy in 6 cylinder version…when they came out the next year…because it captured the forward look of our Plymouth. A dozen years later all the cool kids liked the 55 and 56 chevy. Nice little mid size cars with many ways to juice up the performance. Agree. For nostalgia I preserve a 55 Plymouth identical to my parents Plymouth. I never see a 55 or 56 Plymouth at car shows. I see dozen tri fives every weekend show. Yup very iconic.

The ’58 Chevy as we know it was originally supposed to be the ’57 Chevy. But target dates were not met early on and they knew it would not be ready for the fall in 1956. So, they did a significant facelift to the ’56 and we got the ’57 as we know it today.

Great article. But sadly one more example of publishing before having a real human carefully proofread the copy. In the last line of the second paragraph, I assume you meant “buff body lines”, and NOT “bluff body lines”. Proofreading software will never equal what a human proofreader can do.

Beauty is strictly in the eye of the beholder, and for me one of the most beautiful eras of automobiles was roughly the mid 60s – mid 70s. Putting aside mechanics, speed, power and reliability, and just focusing on pure aesthetics, the 60s-70s produced some really gorgeous vehicles. They were sleek, slender and simply beautiful cars. It was that in-between era when cars still had lots of chrome and lots of style, just before the government started to choke the designers with burdensome safety rules and regulations which has been stifling creativity for the last 40+ years. Yes, the cars are much safer than in yesteryear, but color coded bumpers made of plastic composites and polyurethane (or whatever materials they use) can’t hold a candle to a shiny, gorgeous nicely contoured chrome bumper!:)

My grandfather restored 2 BelAirs, a 1955 Gypsy Red/India Doe Ivory 2 door, and a 1957 Harbor Blue 2 door. I tried to stake claim to the ’55 when I was a teenager, but walked in to the house to see my grandparents and another couple sitting at the kitchen table with stacks of cash in front of them. It turns out, they sold it. Fast forward about 30 years, and my grandfather passed away leaving the 1957 to me. I have made the decision to have the car completed restored again with some modernizing, such as Wilwood slotted power brakes, 383 Stroker crate motor (it wasn’t a numbers matching car), and various suspension upgrades. The interior is perfectly restored, so just upgrading gauge cluster, moving shifter to the floor and adding Power Steering. She has been named AlteredEgo for her mix of modern elements with many original “true to her era” elements. I am beyond grateful for my Grandfather’s gift and will enjoy her and respect her as long as I’m upright and suckin’ air.

I had a 1955 Chevrolet 210 4 door sedan in the early 1980’s. I drove it to high school in the 10th and 11th grades. It was a 6 cylinder, 3 on the tree car. Before I went into the 12th grade, I got a late model 1983 Monte Carlo that had a V-8 and T-top roof. I traded the 55 Chevrolet has part of the down payment. Wished I had both of those cars now. Lol.