Media | Articles

How plastic model cars stoked interest in their real-life peers—and vice versa

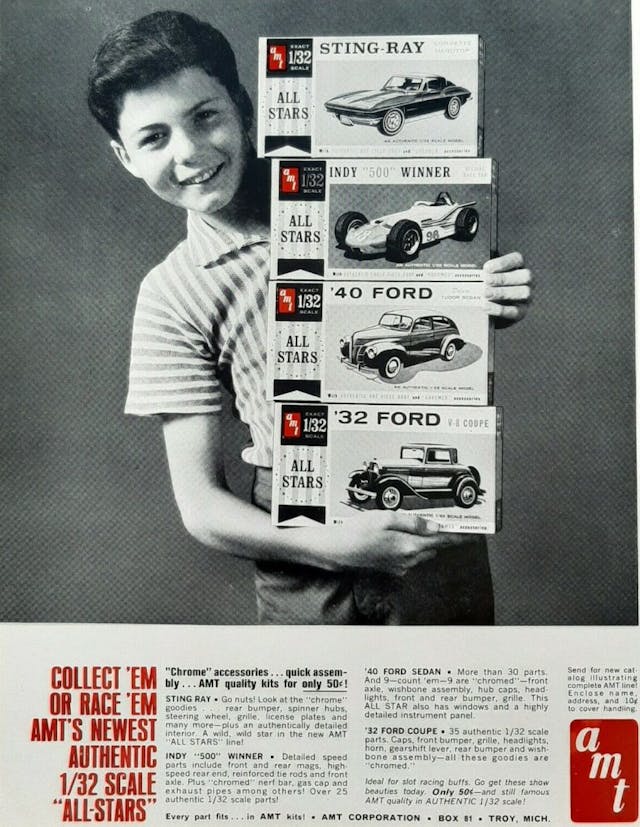

Most car enthusiasts older than about eight years old have likely assembled a plastic scale model car kit at one time or another, though the hobby is long past its golden years of the 1960s. It shouldn’t surprise you that like their full-scale siblings, much of the history of plastic scale-model cars took place in and around Detroit. While California’s Revell and Chicago’s Monogram were major players in the model kit industry, they didn’t concentrate on model cars. It was companies in the Detroit area, Jo-Han, AMT, and later MPC, that provided the foundation for the model car kit industry.

While some histories put AMT as the originators of the plastic model car, that acronym actually stands for Aluminum Model Toys, which Detroit attorney West Gallogly Jr. started in 1948 to make cast aluminum scale-model Fords. Gallogly had family connections to Ford, and the models were marketed as promotional items through Ford dealers.

While plastics like celluloid and Bakelite were in use in the first half of the 20th century, the development of acrylic and other more advanced polymers during World War II gave postwar entrepreneurs new materials to use making consumer goods.

Product Miniature Company, known as PMC, was started by brothers Ed and Paul Ford in Milwaukee in 1946. At the time, car dealers gave away promotional metal cars used as coin banks made by companies like Banthrico. PMC made car shaped coin banks, only molded from cellulose acetate. The company had at least some success as the line stayed in production until 1965. Cellulose acetate, however, has a tendency to warp, and the company was slow to embrace styrene-based plastics, which were both more dimensionally stable and also could be molded in finer detail. Perhaps that was why PMC abandoned making model cars in 1965, at a time when that industry was booming.

In between the founding of PMC and AMT, in 1947 a Detroit-based tool and die maker named John Hanley started a company to make promotional advertising specialties and model aircraft. He also made industrial models. Hanley got into making model cars after producing a model of Chrysler’s then-new fluid drive automatic transmission used for training mechanics. That led to a contract to produce promotional models of vehicles for the automaker. In the 1950s, automakers came to the conclusion that “the little ones sell the big ones,” and just about every brand of cars had promotional scale models, typically in 1:25 scale, that they would ostensibly give away to the children of prospective customers—though the only times my older brother and I got any was after our father or grandfather actually bought new cars.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As Ideal Models took off, a potential trademark conflict with the much larger Ideal Toy company was resolved by renaming the company Jo-Han, after Hanley’s names. While Jo-Han produced models for Oldsmobile, Cadillac, Studebaker, and American Motors, the company was closely associated with Chrysler. It continued to make plastic promotional models until 1979, its last promo model being the 1979 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. AMT made promos for Ford, and later MPC would work primarily with General Motors.

Getting back to West Gallogly, in 1948 he set up AMT in a shop on Detroit’s Eight Mile Road. As mentioned, Gallogly was an attorney with a practice to run, so in the early 1950s he hired George Toteff Jr. to run AMT for him. Toteff was a skilled pattern maker with an understanding of manufacturing. He would often say that a model car company was very much like an actual automaker, with many of the same engineering and production departments, they just made smaller cars. During the industry’s heyday, it made models of virtually every production car built in America. To get a leg up on competitors, model car kit makers even used industrial spies and possibly even bribes to get early details on new car models yet to be introduced.

The design process was the reverse of how the big car companies did it. A typical automotive design studio starts with a sketch, creates a detailed rendering, and then sculpts a scale model, usually in 1:10 scale, before scaling it up to a full-size clay model. At AMT, artists would reproduce the full-scale cars in 1:10 scale, which were then reduced to 1:25 using pantographs.

By 1949, modern injection molding presses started proliferating. Plastic bodies could be molded in a spectrum of colors, eliminating the need for painting. In time, Toteff would also implement a method for vacuum deposition of a chrome-looking finish on plastic that is used to this day in the making of brightwork for actual automobiles.

Gallogly switched to plastic bodies and renamed the company to its acronym, AMT. In the early days of plastic model kits, car bodies were made similarly to how real cars were assembled, glued up from different panels. That made alignment and assembly of the bodies fairly difficult for a child. Toteff developed “side sliding” injection molds that allowed the molding of complete, detailed bodies in one piece, greatly simplifying assembly.

In 1958, someone at AMT, likely George Toteff, came up with what in retrospect was an obvious, though brilliant idea. The promotional car models were sold to the dealers in ready-to-play form, already assembled. At that time, the West Coast hot rod scene was exploding, and custom car makers like Dean Jeffries, George Barris, and Detroit’s Alexander Brothers were putting wild customs on the covers of magazines. Also, at the time, there were the well established model airplane and boat building hobbies.

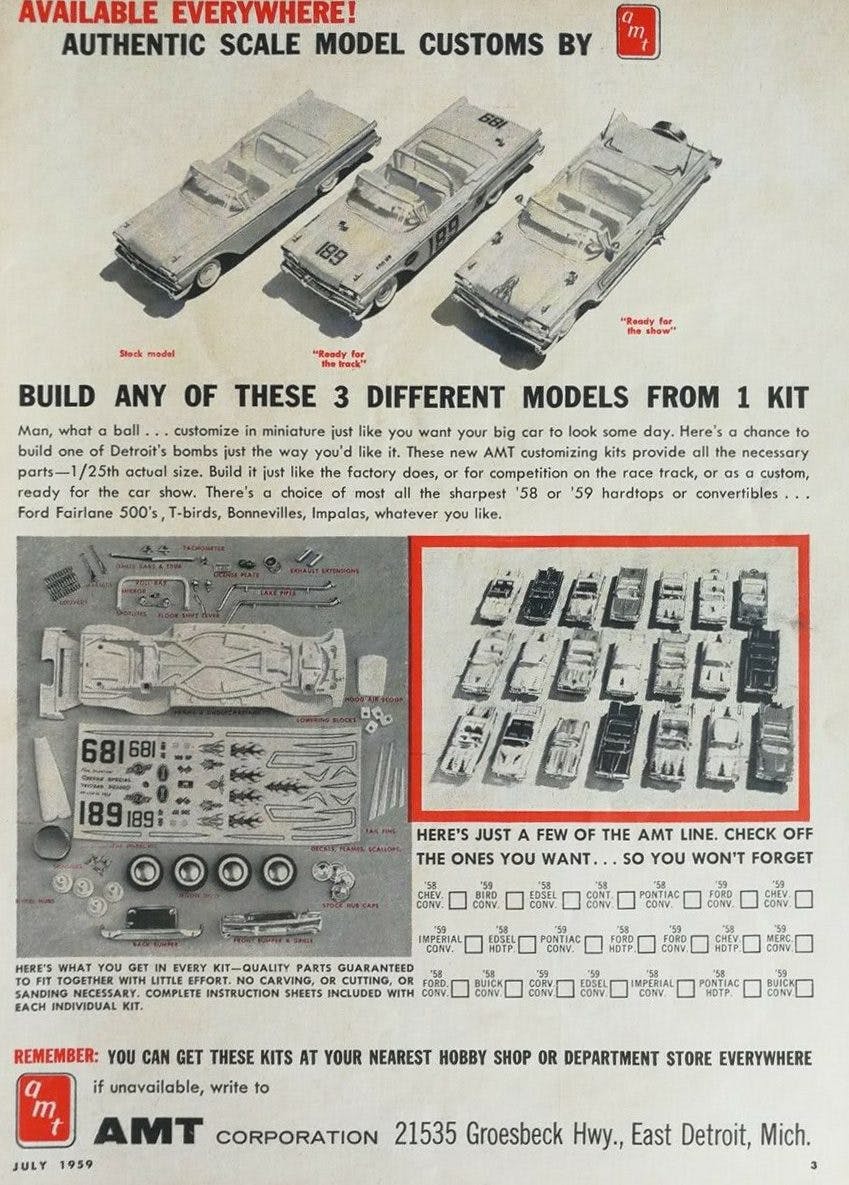

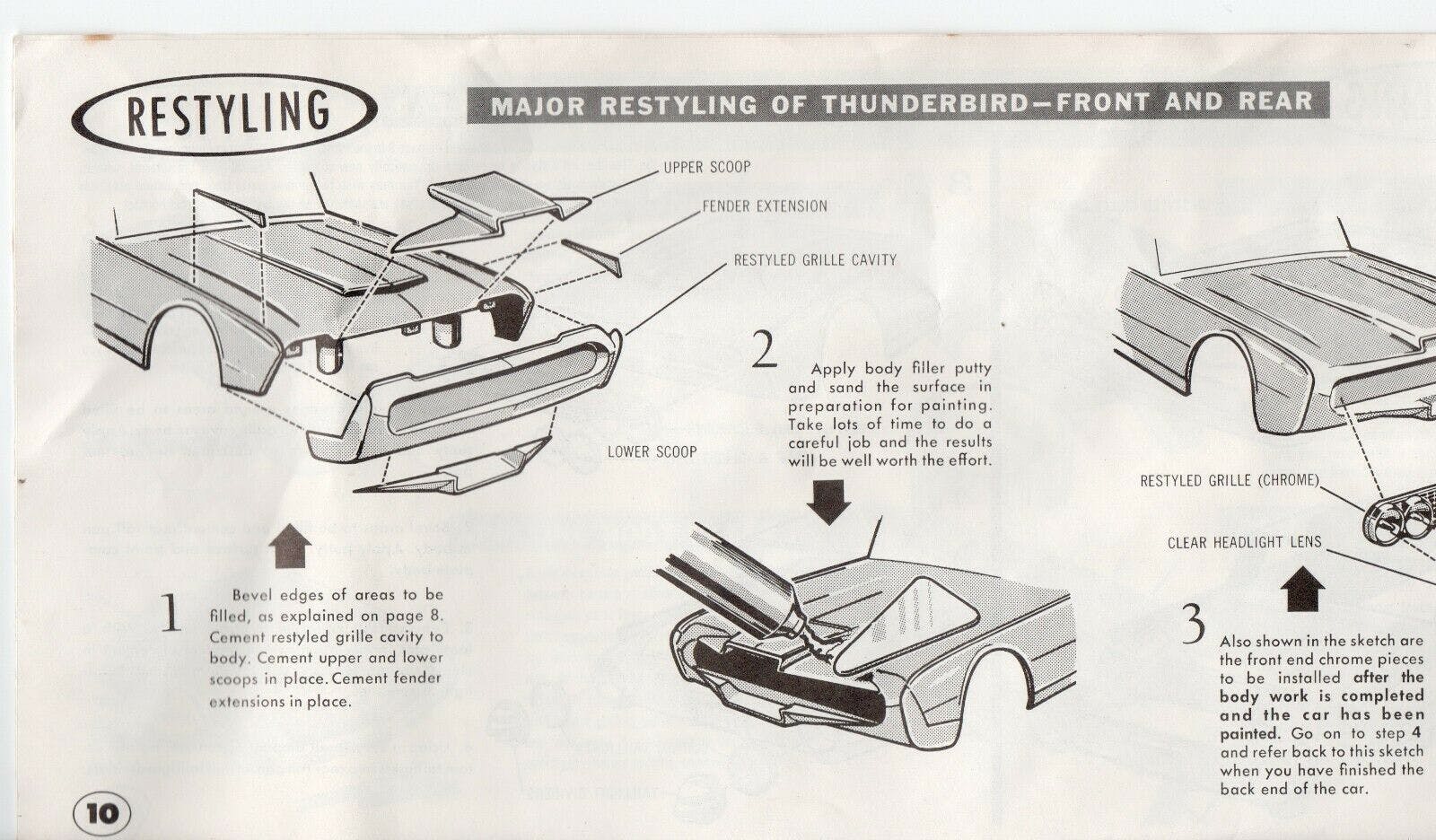

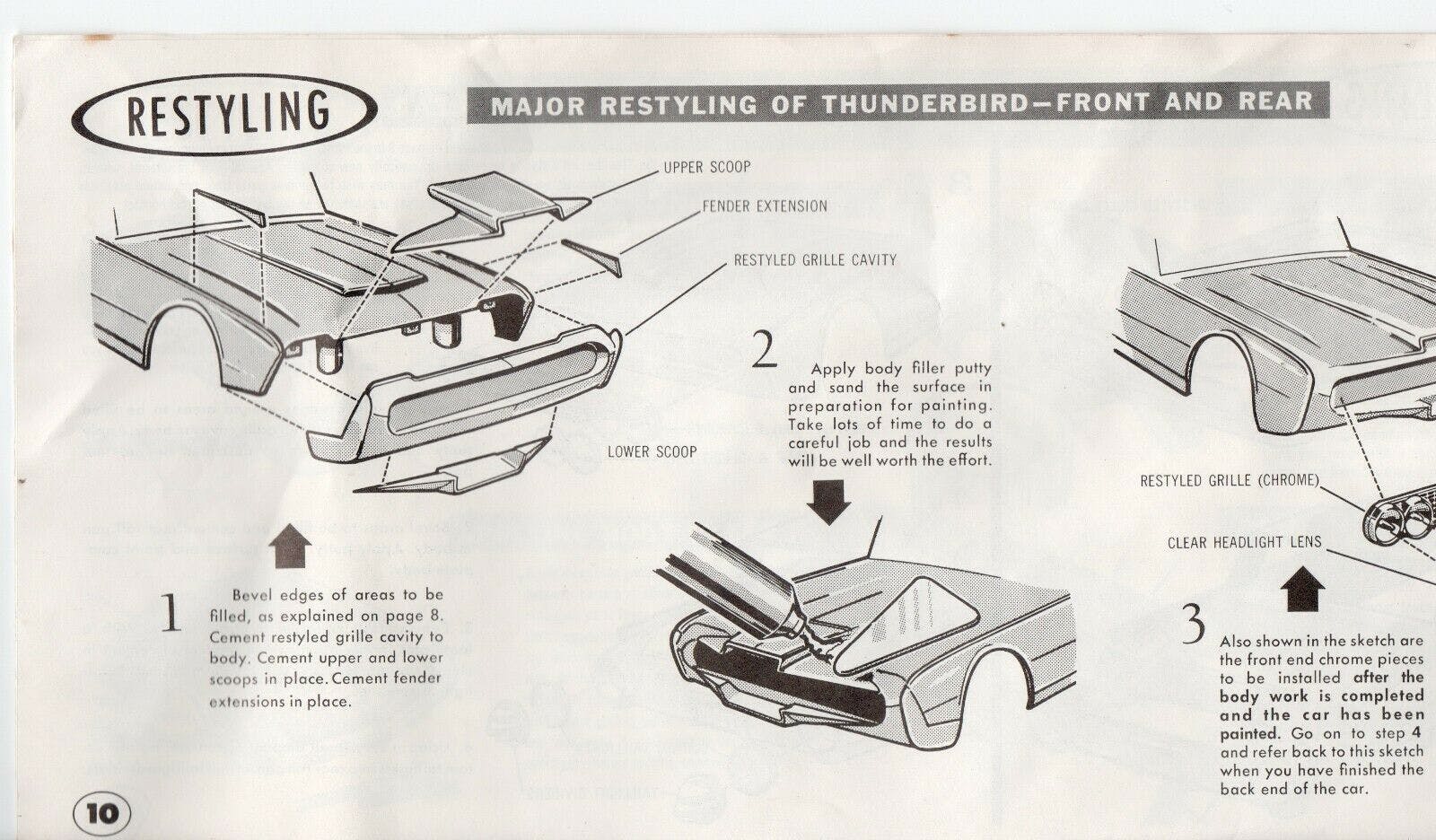

AMT decided to take unassembled promotional models, add some extra parts, including popular automotive accessories like fender skirts and continental kits, and sell them in kit form for the hobby market. They were marketed as “3-In-1” kits that could be assembled three different ways: as a stock production car, some kind of performance or race car, or in customized form. Toteff also figured out that splitting some parts to be molded separately allowed AMT to sell model convertibles and hardtops in the same kits.

One of AMT’s early model kits, for a Buick, sold more than a half-million units. By 1959, AMT offered 10 model car kits, including a Corvette, a Lincoln, and an Edsel model that itself may have sold better than the real thing.

While they were not exactly inexpensive—for example, the 1959 3-in-1 Ford retailed for $1.39, or about $12.50 in 2020 (a lot of money for a kid)—the new kits were a huge success, essentially creating a new segment in the hobby industry. It should be noted that the hobby market is distinct from that of toys in general. That would create problems decades later when large toy companies bought some model kit makers and tried to market model kits through their traditional toy supply chains.

Another innovation of Toteff’s was switching from acetate, which warped, to styrene, which was more stable, could mold finer details, and also could be easily assembled with solvent based glues. In 1959 Jo-Han followed AMT’s lead, moving to the more durable and stable plastic, and also started making 3-in-1 kits.

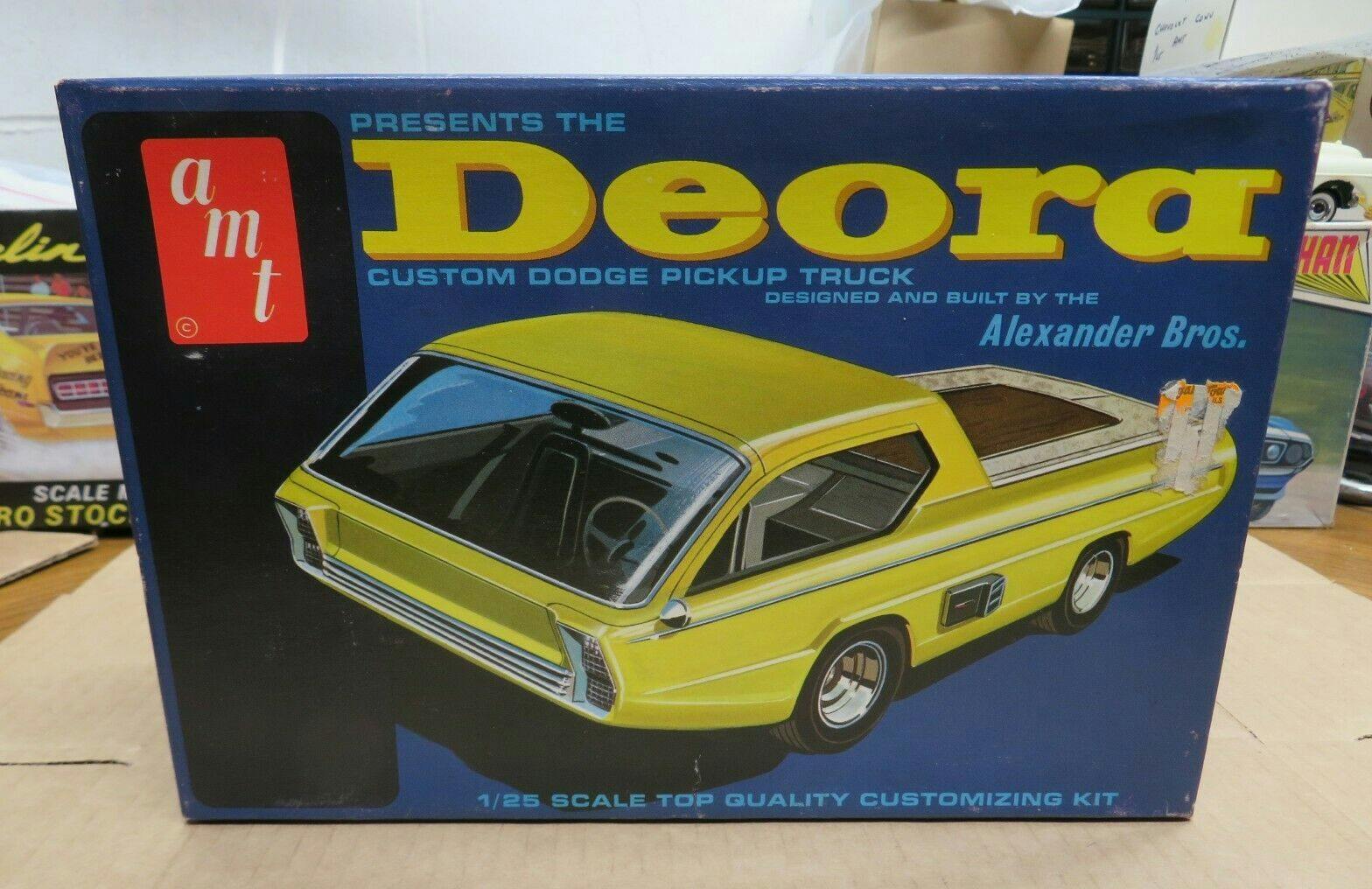

As mentioned above, the custom scene was burgeoning, so AMT made licensing deals with many of the leading customizers of the day, including Barris, Jeffries, Bill Cushenberry, and Gene Winfield. Jo-Han countered with accurate, detailed reproductions of NASCAR racers, starting with Richard Petty’s 1964 Daytona 500 winning Plymouth.

Around that same time, George Toteff decided to leave AMT to set up his own company, Model Products Corporation, better known as MPC, in Mt. Clemens, Michigan, just north of Detroit. The parting was on amicable terms, and there were deals to license molds and models in both directions. Toteff was also able to keep the license with Dean Jeffries, the result of which was one of the most successful model car kits ever, Jeffries’ Monkeemobile for the fabricated-four’s 1960s television series.

While the model car kit industry thrived in the ’60s, a decade later tastes in hobbies had changed. Many of the boys who were active model builders were now teens working on real cars and dating girls, not playing with model kits. Automakers and dealers soured on giving away the relatively expensive, finely detailed promotional models, and after the 1973 oil embargo plastics started getting more costly.

MPC was eventually bought by General Mills, for the food processor’s toy division. Wisely, it retained Toteff, who ended up running Lionel trains after General Mills bought that company too. Ever the innovator, Toteff introduced low-friction wheels and needle bearings that allowed Lionel’s existing engines to pull longer trains. He also introduced the “sound of steam” sound effects to model trains.

In 1977, AMT was bought out by Lesney, the British maker of Matchbox diecast models, and its facilities were moved out of the Detroit area to Baltimore. In the early 1980s, AMT was saved from brand death when it was sold to modelmaker Ertl, just prior to Lesney’s bankruptcy.

When General Mills decided to divest from its core businesses, Ertl also bought MPC. Both MPC and AMT brands then operated under Ertl, which has since sold them to Round 2, in South Bend, Indiana, a company which also owns the Lindberg and Hawk model brands.

Jo-Han stayed in business until 1991 by reissuing models based on their old molds. That year the company was bought by Seville, a Detroit area vendor of plastic parts to the automotive industry, although things didn’t work out and Jo-Han models disappeared from shelves for a few years.

In 2000, model enthusiast Okey Spaulding bought the Jo-Han brand and molds from Seville, putting some classic models back into limited production, but that enterprise seems to be now restricted to selling parts, not complete model kits.

George Toteff had some success reviving the Lindberg brand of model kits in the early 1990s, using old molds. He died in 2011 at the age of 85. He once said that the only job he ever had was making models.

Toteff had few equals. Though it has produced many, many millions of model kits, the model car kit industry was actually the product of a small number of men: Gallogly and Toteff at AMT and MPC, Hanley at Jo-Han, Revell’s Lew Glaser, and the men who founded Monogram, Jack Besser and Bob Reder.

That small circle created a hobby that has provided countless hours of entertainment for millions of people, young and old.