Media | Articles

How Ford’s Model T helped create labor unions and the American middle class

The Model T was more than a car; it was a game changer—and not just in the auto industry. As the Historic Vehicle Association points out in part three of its four-part series The Fifteen Millionth Ford Model T, Henry Ford’s iconic automobile and his perfection of the moving assembly line caused a ripple effect that ultimately created the upper middle class … and suburbia … and commuting … and also, much to Ford’s chagrin, labor unions.

The third installment of the documentary, titled “Unexpected Consequences,” was released earlier today as part of the HVA’s Drive History video initiative, which will feature vehicles on the National Historic Vehicle Register as well as interviews with influential automotive historians and preservation experts. Videos are scheduled to be released every Wednesday.

Part III begins with a newsreel clip from the era, along with these prophetic words: “The age of the automobile changed every aspect of American life.” Indeed it did, and no vehicle did more to change American life than did the Model T. As historians point out, the car had a domino effect on the culture.

“When [the Model T] first came out in late 1908, it cost $850, which was not cheap … but it was the best value on the market,” says Bob Casey, Retired Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford museum. “Then Ford Motor Company set out on a relentless drive to lower the price. They kept improving production methods, they kept changing the parts on the car to make them cheaper to produce …”

“Henry Ford said that every time he dropped the price by a dollar, he gained 1000 customers,” says Michael Skinner, Ford Avenue Piquette Plant trustee.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“At one point you could buy a Model T for $295,” Casey adds. “Of course, in Ford’s desire to drive the price of the Model T down, that eventually led them to stumble onto the whole assembly line.”

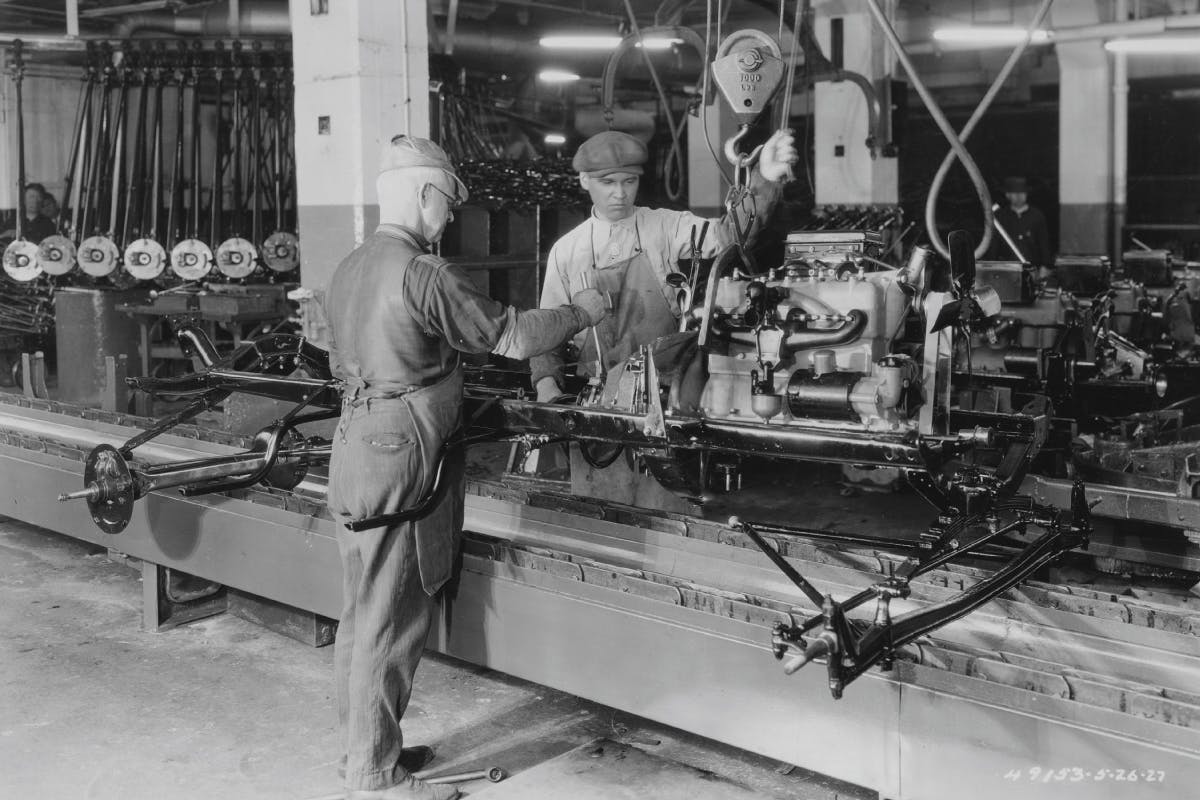

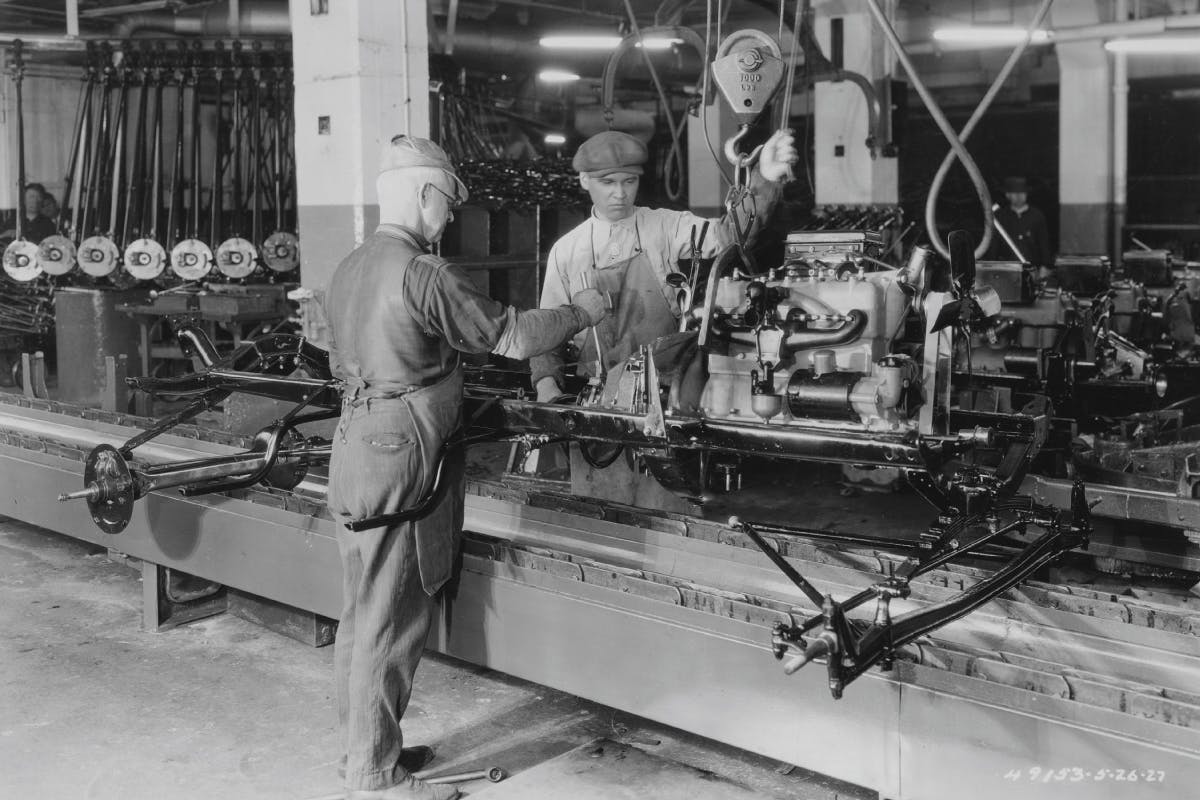

Matthew G. Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford, explains that Henry Ford didn’t invent the moving assembly line, but he did perfect it.

“Moving assembly lines had been around for a long time, and again this was a case when Ford was looking at other industries,” Anderson says. “Oddly enough, he was looking at the meat packing industry, where they would bring in animal carcasses, and they would move them on a line. Workers would take parts off those animals, and by the end of the line you have them leaving in cans.

“Ford said, ‘What if we turn that around and add parts to the vehicles that move through the plant?’”

As the newsreel explains, “Each man on the line became a specialist. He did one thing, and he did it perfectly, and passed the work along to the next man.”

The introduction of the moving assembly line reduced the build time from 12.5 hours to 93 minutes. By 1924, it took only 12 minutes to assemble a Model T from start to finish. The problem was, assembly line work was extremely tedious and the days were long. Workers began to quit. Then Ford announced that he was more than doubling assembly workers’ wage—from $2.34 per day to $5 per day—and suddenly so many men came looking for employment at Ford’s Highland Park plant that the regular workers couldn’t get in. Casey says “they had to bring out the fire hoses” to clear the crowd.

Potential workers came not only from across the U.S. but also from Europe. Most of the immigrants did not speak English, so Ford set up schools to teach the language and also established a sociological department to visit applicants’ homes and determine if they were worthy of that $5-per-day wage.

“There was a huge dollop of paternalism here that no one would accept today,” Casey says. “Ford was trying to encourage families to spend it wisely, spend it on the family, spend it responsibly. Be a responsible citizen—that’s what he wanted.”

The Model T offered unskilled workers a comfortable living, and the car itself allowed them to live outside the city and drive back and worth to work.

As Christian Overland, former executive vice president and chief historian at The Henry Ford, so aptly explains, the growth expanded outward from the cities. “When you leave 1915 and you go into the 1920s, people are building on the outskirts of towns, not only in towns. And then … boom!”

Of course, such a huge community of unskilled workers soon realized it possessed power in numbers. The workers could demand significant changes if they only banded together. The birth of labor unions turned out to be a thorn in Henry Ford’s side, which will be explored in Part IV, “The End of an Era,” next Wednesday.

We’ll be sure to keep you posted about each new HVA episode. You can also stay in the loop by following the HVA on Facebook, Instagram, and Youtube.