Media | Articles

How Detroit’s transportation landmarks are—and aren’t—being saved from ruin

Across the digital world, most published content is bite-size, designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the breadth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears. Pour your beverage of choice and join us each day this week for a Great Read. Want more? Have suggestions? Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: editor@hagerty.com

The signs are everywhere, but they might as well be nowhere. Yellow markers, warning against trespassing and promising that violators will be prosecuted, no longer serve as deterrent, if they ever did. As Detroit’s once-proud Packard assembly plant continues its slide into ruin, interlopers have turned the automotive landmark into a giant dump. The buildings, or their remains, hold unwanted junk of all sorts—as large as cars and boats, as small as household waste.

Now it appears the brick and mortar will soon follow suit. After a foreign developer abandoned his redevelopment plans for the plant, the City of Detroit was given permission to level the place in the name of public safety. The wrecking ball could get to work any day. When that happens, a hundred-year-old landmark and long-contested symbol of a struggling city’s glory days will be gone for good.

Detroit being Detroit, the Packard plant is not alone. Eleven miles to the west, the former American Motors Corporation headquarters will also meet the wrecking ball as part of a redevelopment costing $66 million. Other historical industrial/transportation buildings are also undergoing change. In the Corktown neighborhood, the 18-story Michigan Central Station, opened in 1914, is receiving the finishing touches of a reported $738 million makeover. (USA Today says the number is closer to $1 billion.) Like the Packard plant, Michigan Central has been deserted for years. Unlike that plant, it is on the way to becoming the centerpiece of a new high-tech campus for the Ford Motor Company. Meanwhile, the long-vacant Fisher Body Plant 21 on Piquette Avenue is set to be repurposed as Fisher 21 Lofts, a $134 million project.

Detroit has been a home of “ruin porn” since the tail of the last century—these buildings are but the four most visible and well-known. Depending on where you stand, their diverging futures are either exciting or tragic.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“I grew up in the city. I know all these buildings well, and yeah, you’d like to preserve them, but it’s a balance,” says Tim Conder, vice president of acquisitions for NorthPoint Development, which is redeveloping the AMC site. “Sometimes you can preserve them, sometimes you can’t. People compare Central Station [which is essentially an office building] with AMC, but you’ve seen AMC—that’s not an office market out there … It just wouldn’t work.”

Claire Zimmerman is an associate professor of architecture at the University of Michigan. She favors at least partial preservation whenever possible. So much of Detroit’s architectural history, she says, has already been lost.

“When Detroit grew so fast [in the early 20th century], one of the defining typologies of the city, in terms of architecture, was the daylight factory,” she says. “It was a significant invention because daylight factories were so well lit, and the conditions were so much better than the timber factories and mill buildings. These factories were really the fabric of the city.”

The remaining daylight factories are valuable, Zimmerman says, not just for their history, but because they’re also big, well-built, and versatile. “You can use them for pretty much anything … They’re really kind of flexible. But they’ve been demolished one after the other.”

The problem with saving these buildings, Conder says, is the cost. And there are other considerations with structures like these.

“If you want to maintain the historical aspect of it, you want to get tax credits,” he says. “That’s a long process, it’s a tedious process, and it’s not an easy process. It’s like restoring a car; do you want to do it halfway? Maybe there’s adaptive reuse, and you can include portions of a façade, but that still costs money. That wasn’t factored in at AMC. That building is just too far gone.”

The Motor City is a place both shackled and bolstered by its past. These four buildings are a tangible version of Detroit’s complex relationship with history, but they’re also deeply representative of how the city operates and has always operated. How optimistic plans born of good intention can repeatedly stall. How tradition matters, but long periods of decline can bring too much entrenchment in the past. And how the city’s very strengths can stand in the way of it becoming the best modern version of itself.

The undeniable truth is that things in Detroit are changing, and not always as everyone would like. So, we went there to see the condition of these historic for ourselves.

AMC Headquarters

The former American Motors Company headquarters and factory sit at 14250 Plymouth Road, about 10 miles northwest of downtown Detroit. At 95 years old, the AMC complex is the youngest of the four sites in this story. It is also the only one not built from the start for the transportation industry.

Designed by the city firm of Smith, Hinchman & Grylls, and built under the direction of architects Amedeo Leoni and William E. Kapp, the facility’s administration building and factory were completed in 1927. They were constructed for the Kelvinator Corporation, which made home refrigerators. Originally 1.5 million square feet (later expanded), the park included a tall office tower facing Plymouth Road. Behind that building sat a huge, three-story factory in multiple sections, plus a self-contained power plant. Kelvinator’s name was chosen to honor the British physicist Lord Kelvin, who developed a scale for measuring absolute temperature. A Kelvin quote was once engraved above the doorway to the plant’s administrative entrance: “I’ve thought of a better way.”

For Kelvinator, the better way involved a merger with Nash Motors in 1937. In 1954, the resulting company, Nash-Kelvinator, merged again, this time with Detroit’s Hudson Motors, forming the American Motors Corporation. When AMC relocated its headquarters to suburban Southfield in 1975, the Plymouth Road facility refocused on Jeep. In 1987, when Chrysler bought AMC, the complex was renamed the Jeep and Truck Engineering Center.

Twenty years later, in 2007, Chrysler filed for bankruptcy. The Plymouth Road complex closed in June 2009.

Drama began soon after. In 2010, the AMC facility was sold to Terry Williams for $2.3 million. (The original ask was $10 million.) Williams announced that he was going to turn the facility into a school for autistic children, but he began stripping the factory of scrap metal, which authorities said “disturbed asbestos-containing materials and released ozone-depleting substances.” In 2014, Williams was convicted of violating the Clean Air Act and sentenced to 27 months in prison. The AMC property, seized by the court, was transferred to the Wayne County Land Bank. It wound up as property of the City of Detroit in a 2018 land swap. A subsequent environmental-cleanup operation included demolition of the power plant and much of the rear of the factory.

After the property sat vacant for more than a decade, Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan held a press conference on December 9, 2021. NorthPoint, he announced, would demolish the remaining buildings and replace the complex with a $66 million warehouse development.

“One by one,” Duggan said, “we are taking down the massive vacant buildings that for too long have been a drain on our neighborhoods and our city’s image, and putting something new in their place … (and) I expect we will be announcing plans for other such sites in the city very soon.”

Not everyone was so excited. Because NorthPoint pursued public incentives (the firm eventually secured $32.6 million in brownfield TIFs), the Missouri-based developer was required to hold public meetings about its plans for the site. Those meetings resulted in “a ton of pushback” from preservationists, Conder says, and a December 2021 editorial in Crain’s Business News—the headline was “Detroit needs a plan to save its industrial history”—advocated saving the historic structure. The Crain’s story immediately prompted an open letter to the editor from neighborhood residents, who were thrilled that something was finally being done with the abandoned complex. It was an eyesore near a public park, they claimed, one with racist ties to the area.

“The joy in our neighborhoods was indescribable,” the letter read. “For many years, that monstrous abandoned AMC site has devastated our community, driving down the home values of those who stayed, crippling any effort to rebuild commercial businesses on Plymouth, and permanently affecting our children’s view of the neighborhood where they are being raised … We won’t sit by while outsiders, who couldn’t find our neighborhood without a map, presume to tell us how much we should value their precious ‘Art-deco neighborhood landmark.’”

NorthPoint’s Conder, despite his admitted affection for historic buildings, agrees: The time to save the AMC facility has come and gone.

“Do you know how long that building has sat there untouched?” he says. “The moment someone is interested in the site, all of a sudden people come out of the woodwork and say, ‘You can’t do that …’ No one cared about it until we got it under contract. Talk to the community; they’re happy to see it go. Hey, I love historical buildings and want to preserve as much history as we can, but again, you have to balance that with economics and business going forward.

“The problem with Detroit is, there are not enough readily available sites to develop. So, when requirements come out for space in the city, they quickly realize there are no sites available, so they immediately look in the suburbs. And there are sites available in the suburbs, so none of the business stays in Detroit. What we’re really trying to do is help the city of Detroit create developable sites that are readily available … We’re trying to remove blighted properties, bring in new projects, bring in new jobs to the area.”

Northpoint says the plan to build a 794,000-square-foot warehouse or light industrial space on the former AMC campus at Plymouth Road will create 350 permanent jobs and 100 temporary construction jobs. Demolition is expected to begin this month. Conder says it will take approximately six months to “prepare the pad” and 12 months to complete construction.

“We approach these as spec developments, meaning we don’t have a tenant,” he says. “We buy the property, tear it down, clean it up, and go vertical—all while talking to prospective tenants.”

In addition to cost, Conder says, the number-one reason NorthPoint never considered saving even a portion of the AMC structure is that every bit of the 50-acre site is needed to deliver adequate warehouse space.

University of Michigan’s Zimmerman has not visited the AMC headquarters recently, so she admits that it might be too far gone. Regardless, she says, the facility never should have reached this point. On historic Detroit buildings in general, she reasons, “The City of Detroit is not thinking about the city’s heritage here; they’re thinking about the city’s budget … (but) once these things are gone, they’re just gone. You can’t recapture them.

“I think it’s a little bit of a failure of the public realm not to have some provision to guard the history of the city and its significant buildings. Yes, they require some maintenance, and you’d have to do serious work to bring them back up to a usable state, but what do we have city governments for? We have them to keep law and order, and to preserve civic identity.”

Fisher Body Plant #21

Daylight factories, Zimmerman says, can be used “for pretty much anything.” Perhaps as evidence, the 600,000-square-foot Fisher Body Plant 21 is in the process of being resurrected as Fisher 21 Lofts. Standing at the corner of Piquette and Saint Antoine—but officially listed at 6051 Hastings Street—Fisher 21 is only a few blocks east of the refurbished Ford Piquette Avenue Plant Museum, where the Model T was born. Visible from both I-94 and I-75, Fisher is often referred to, Zimmerman says, as “the big white factory with all the graffiti.”

Since it was abandoned, she notes, the plant has been a magnet for “urban explorers, music-video performers, and what you might call informal social events, like raves. It has had quite a devoted audience.”

Designed by architecture firm Smith, Hinchman & Grylls, the Fisher factory was constructed in 1919. The company operated as an independent coachmaker, producing bodies for Cadillac and Buick, before being purchased by General Motors in 1926. Among Fisher 21’s many production roles was the assembly of tanks and war materiel during both World Wars. It built limited-production limousine bodies starting in 1955.

Historically speaking, Zimmerman says the significance of Fisher Body goes beyond the war effort and vehicles produced.

“Sort of controversial was Fisher’s role in the emergence of the UAW—not so much in Detroit, but in Flint, where sit-down strikes occupied Fisher Body No. 1. It essentially gave the UAW a foothold in Detroit, and that ultimately included all of the Fisher plants and other automotive plants in the city. No matter how you feel about the union, it was a feature of midcentury American history, and these modern factories helped to bring it into being.”

On November 29, 1982, GM announced that Fisher Plant 21 would cease operations, citing the building’s inefficiency as reason for closure. The facility was officially shuttered two years later. In 1990, the Carter Color Coat Company purchased the plant, using it for industrial painting. When Carter declared bankruptcy in June 1992, Fisher 21 was abandoned for good. The City of Detroit took ownership of the plant in 2000, and the Environmental Protection Agency began remediation work in 2008, removing and disposing of soil, contaminated equipment, and underground storage tanks.

In March 2022, Mayor Duggan, echoing his AMC comments just four months earlier, announced that Fisher 21 would no longer be a blight on the city. Duggan exulted in the news that the former factory would be saved and redeveloped as a $134-million residential building with 433 apartments and ground-floor retail: “It is very exciting to be able to save this historic landmark and put it to work for the residents of this city for decades to come.”

The Fisher 21 Lofts venture is believed to be the largest African American-led project in Detroit’s history. It is helmed by developers Gregory Jackson of Jackson Asset Management and Richard Hosey of Hosey Development. In a press release, Jackson said, “This project is being done by Detroiters and for Detroiters. This project is proof of the potential of Detroit, its spirit, and its people. We are honored to become stewards of this forgotten piece of the city’s storied past and turn it into a key piece of its future, bringing catalytic investment, quality housing, and destination retail to this proud neighborhood.”

According to the Detroit News, the Fisher 21 Lofts project triggers a city ordinance that requires developers to work out a benefits package for the community. Project officials have promised to hire city workers and contractors.

“Not only will they be taking Fisher Body 21 from blight to beauty,” Duggan tweeted, “they have committed to making sure Detroiters are able to take part in the redevelopment.”

Fisher 21 Lofts will be a mix of studio, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom apartments, and at least 20 percent of them will be at or below 80 percent of the area median income. Designers with architectural firm McIntosh Poris Associates are planning 28,000 square feet of commercial space and 15,000 square feet of co-working space, plus a two-acre roof with views of the city, a quarter-mile walking track, an indoor lounge, a fitness center, and dog areas.

Zimmerman, naturally, is elated.

“The Fisher Corporation had so many of these body plants—I mean, this is number 21—so to me it’s representative of a type that was widespread across the United States,” she says. “I think it’s going to be great as a refurbished building. Some of the splendor of these ruins is lost when they’re reused, but it’s far better that they be reused, than demolished.”

Michigan Central Station

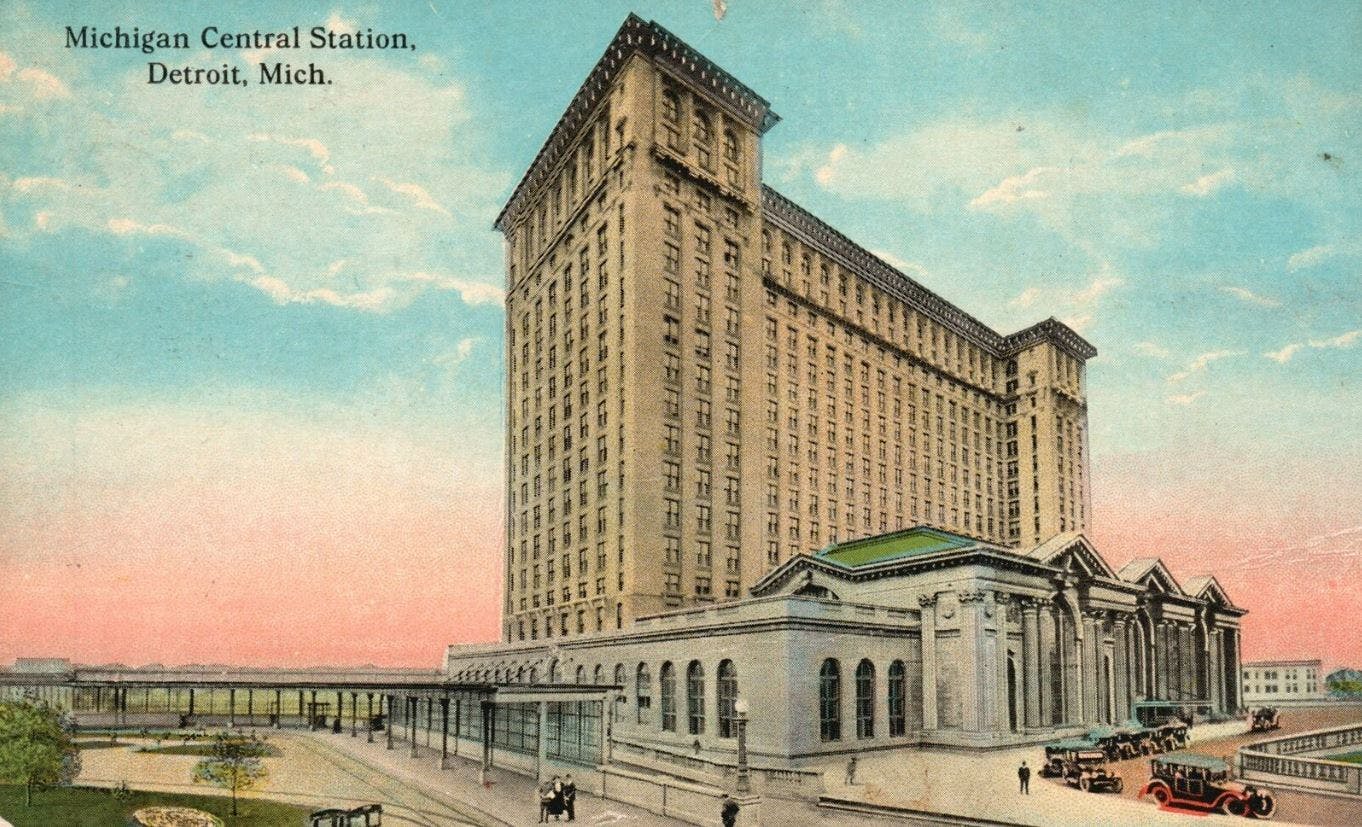

Years before airplanes became the preferred choice for long-distance travel, Michigan Central Station—located at 2001 15th Street, southwest of downtown—served as Detroit’s transport hub. To acquire the space required by the 500,000-square-foot structure, the city began buying out homeowners and condemning property as early as 1908.

Hastened by a fire at the city’s old depot, Michigan Central opened five years later—and two weeks early—on December 26, 1913. The mammoth building, a three-story train depot underneath an 18-story office tower, was a collaboration between architectural firms Warren & Wetmore of New York and Reed & Stem of St. Paul, Minnesota. The two firms also created New York City’s Grand Central Terminal.

For decades, the glistening marble floors, elegant bronze appointments, and 54-foot ceilings of Michigan Central’s majestic main lobby bore witness to soldiers heading off to war, sad goodbyes and happy hellos, and the comings and goings of entertainers and politicians. As historicdetroit.org so aptly put it, Michigan Central also served as Detroit’s Ellis Island, where generations of Detroiters “first stepped foot into the city,” pursuing factory jobs and a better life.

At the station’s opening it represented the tallest railroad station in the world and was the fourth tallest building in Detroit. The Michigan Central Railroad, a subsidiary of the New York Central, invested $16 million (nearly $450 million today) in the grounds, including the office building, the rail yards, and an underwater rail tunnel to Windsor, Canada. The station itself cost $2.5 million and featured a restaurant, a main concourse with copper skylights, a lunch counter, and bathing facilities.

At the beginning of World War I, when American rail travel peaked, more than 200 trains left Michigan Central each day. But as the auto and airline industries grew, train travel began to wane. In 1956, historicdetroit.org says, the New York Central System offered Michigan Central Station and 405 other passenger stations for sale for $5 million ($55.5 million today). There were no takers. Railroad companies began to merge, pooling their resources. In 1971, the U.S. government formed Amtrak, and there was a glimmer of hope as an oil crisis that hurt the auto industry sparked an uptick in rail travel. Locals applauded when Michigan Central’s main waiting hall underwent a $1 million upgrade in 1975, but the depot was never able to return to its former glory or retain enough riders to stay afloat. By 1985, as few as six trains per day passed through Michigan Central. On January 5, 1988, the last train rolled out, bound for Chicago.

Potential buyers and tenants came and went. So did trespassers, looters, and vandals. At one point there wasn’t a single unbroken window in the place, and water filled the basement. In 1995, the station was purchased as an investment by billionaire Manuel Moroun, who refused to spend any money on its upkeep until he found a suitable purpose and tenant.

Finally, on June 11, 2018, the Moroun family announced that the depot and surrounding property had been sold to Ford Motor Company, for $90 million. Ford said the building would become the centerpiece of a 1.2-million-square-foot Detroit campus focused on new technology, an area it has since named the Michigan Central Innovation District.

Multiple requests to interview a Ford representative familiar with the project were unsuccessful, but officials have said that Michigan Central will serve as hub of a 30-acre facility dedicated to entrepreneurs, workforce development, and testing. Some 5000 workers—half of them Ford staff—are expected to be employed there. Google has signed on to become a district “founding member,” providing cloud services and training for students and job seekers.

“This is not going to be a Ford campus,” Ford Motor Company executive chair Bill Ford said, at a press conference. “This is going to be a campus where entrepreneurs, big and small, (will) help develop the future.”

The Michigan Central renovation is expected to be completed in 2023. “I’m thrilled about it,” University of Michigan’s Zimmerman says. “What they’ve done is really kind of amazing.”

Describing the massive transformation of the old train depot, which has received $126 million from the state of Michigan, Bill Ford said, “We are in the process of turning this from a national punchline into a national treasure.”

Packard Plant

Once upon a time, many hoped the same would be said of Detroit’s Packard plant. The gargantuan facility, once the standard-bearer of modern automotive factories, is now a globally recognized symbol of urban decay. Part of the complex will soon be torn down. Like the AMC headquarters, the plant has been subject of debate for years.

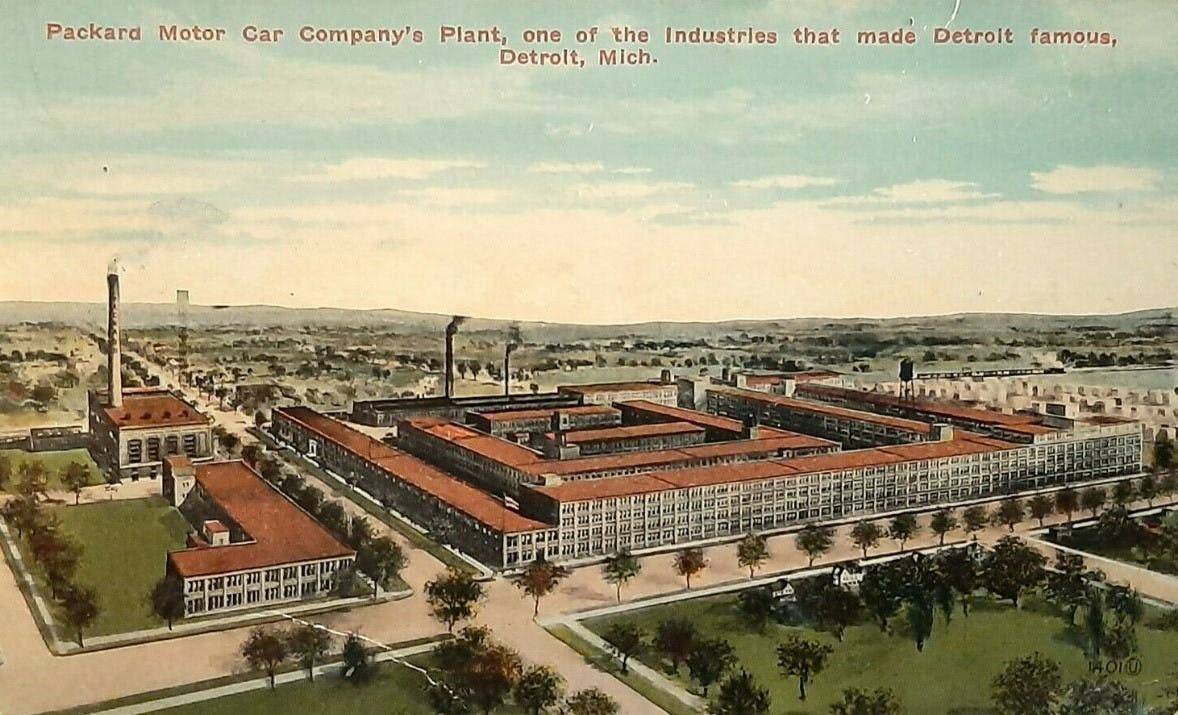

Just after the turn of the 20th century, investors persuaded the Packard Automotive Company to move its headquarters from Warren, Ohio, to Detroit, and company president Henry Joy tasked Albert Kahn to head up the project. Built on 40 acres of pastureland on Detroit’s east side, at 1580 East Grand Boulevard, the first buildings opened for business in 1903. With 10,000 square feet of floor space, the Packard factory was considered the finest and most-efficient automotive plant on earth.

From 1903 to 1905, Kahn built nine structures at Packard. Then he decided those buildings were too cramped and didn’t provide enough light. While constructing building #10, he improved the design—more windows and open space, for better light and ventilation, to make Packard workers more comfortable and more productive. Kahn tapped his brother, engineer Julius Kahn, to design a trussed-concrete rebar reinforcement system. The resulting masterpiece became the most well-known of the daylight factories. Kahn quickly renovated those nine earlier buildings in similar fashion, and other manufacturers soon followed his lead, even outside the car industry. The complex would eventually comprise four million square feet of factory space and employ up to 40,000 workers at its peak.

“Albert Kahn was a giant in Detroit’s heroic age, the visionary who created the humane ‘daylight factories’ for Packard Motor and Henry Ford,” author Michael H. Hodges writes in Building the Modern World: Albert Kahn in Detroit. “And in the process, (he) helped birth both modern manufacturing and modern architecture.”

Owning a Packard automobile was considered prestigious, and buyers were considered particularly intelligent for doing so. Packard vehicles were known for their cutting-edge features, which included the modern steering wheel and air-conditioning in a passenger car. Following WWI, Packard made the transition from hand-built products, high in labor hours, to production-line assembly. In 1939, it constructed a bridge over East Grand Boulevard to connect the north and south halves of the plant, and that bridge became a landmark.

Tasked with building Rolls-Royce aircraft engines during WWII, the Packard Plant required further expansion and upgrades, and additional improvements were necessary following the war. By the mid-1950s, however, the plant’s multistory layout had become obsolete. Worse, sales were down. In 1954, Packard merged with Studebaker—also struggling financially—and two years later, production was moved to a smaller plant on Conner Avenue. The last true Packard from East Grand Boulevard rolled off the line on June 25, 1956.

Portions of the Packard site were used by numerous small businesses until the late 1990s, when most of the structures were abandoned, left to scrappers, squatters, and the elements. The last tenant moved out more than a dozen years ago. Wayne County eventually took ownership of the property, offering it to the highest bidder in a 2013 tax-foreclosure auction.

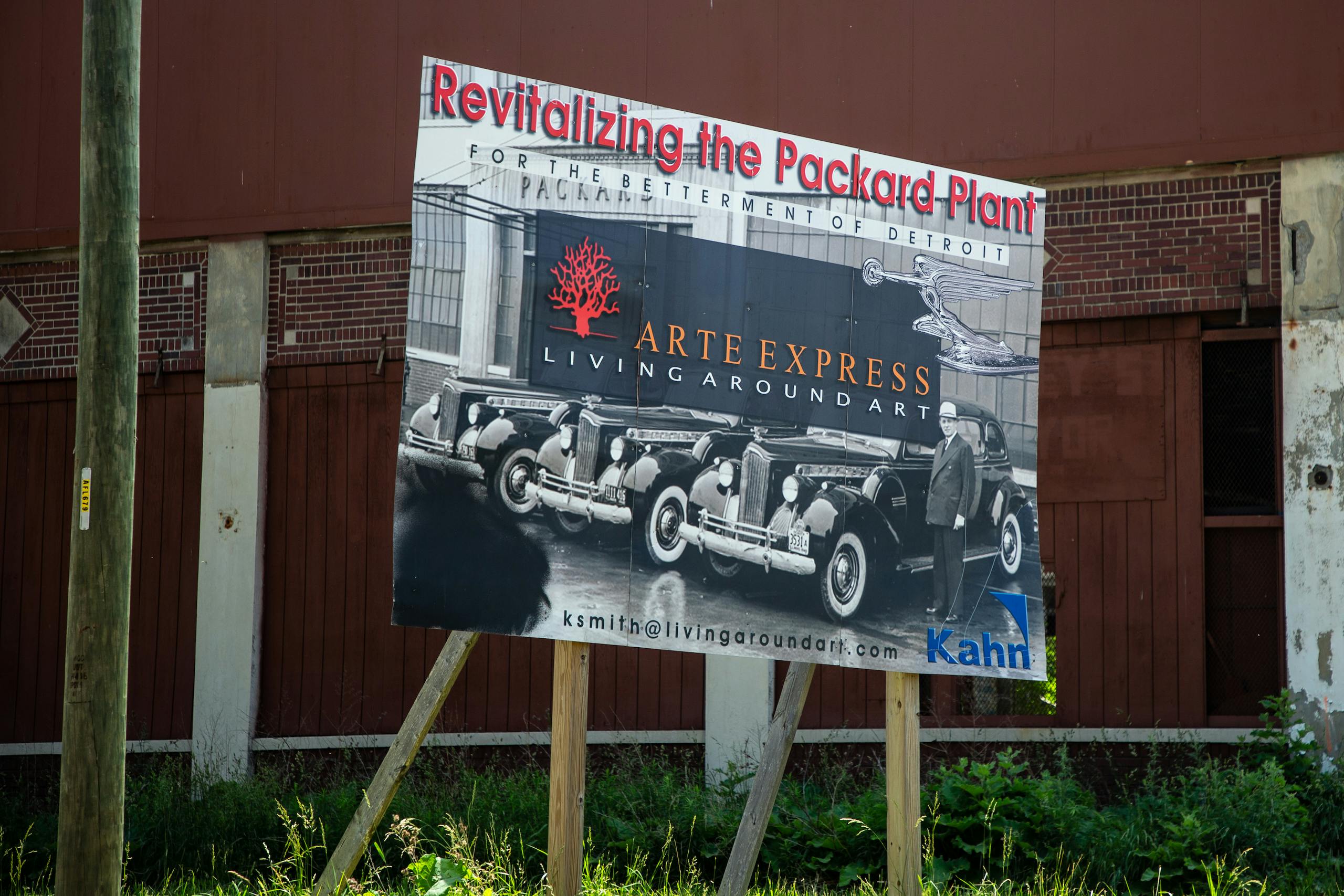

Despite many years of neglect and abuse, Packard’s reinforced concrete structures were then mostly intact and structurally sound. Peruvian developer Fernando Palazuelo bought the complex, two 20-acre sites, from Wayne County for $405,000. Palazuelo’s local company, Arte Express Detroit LLC, immediately began cleaning up the property, and in 2017 it officially broke ground on a 15-year, $350 million plan to redevelop the complex into a mixed-use site.

“I was really impressed (with) the power, the charisma, and the future,” Palazuelo said. And then, quoting Napoleon, he declared, “I assure you, we will not fail.”

Zimmerman believes Palazuelo was sincere. “I’ve been there many times over the years,” she says. “The first few times, it was like they’d just walked out the previous day and left everything behind … But the last time I was there—in 2018 or ’19—all of that stuff had been cleared away. The floor plates were clear, and you got the sense that he was planning something new for that building, that it had been prepared for that.”

There was a bit of a setback in January 2019 when the iconic bridge collapsed and had to be razed, and then a year later the COVID-19 pandemic hit. In November 2020, Palazuelo announced that he was scaling back his original plan. In October 2021, a lack of progress caused him to lose tax incentives tied to the plant’s development. That resulted in Arte Express announcing plans to sell the site for $5 million.

Company representatives have not commented publicly since.

After Palazuelo’s attorney missed a March 24, 2022 court appearance to address safety issues at the Packard site, Wayne County Circuit Judge Brian Sullivan ordered Palazuelo to immediately raze the structures and foot the bill. Sullivan, calling the crumbling Packard Plant a “public nuisance,” said it threatened “the public’s health, safety, and welfare.”

When Palazuelo missed a court-ordered deadline of April 21 to apply for a demo permit, the city began seeking bids from demolition contractors. On July 12, the Detroit Demolition Department announced that it had selected Michigan contractor Homrich Wrecking Inc. to perform partial demolition. The $1,685,000 contract will be paid for using funds available through the American Rescue Plan Act.

Charles Raimi, attorney for the City of Detroit, expressed frustration and disappointment when he told Detroit’s Fox 2 News in April that Palazuelo “never delivered on anything. He just left this horrible, blighted, dangerous property sitting in the middle of the city for years … all these grand plans … turned out to be not true.”

Regardless, for historians, there remains a flicker of hope. According to a report in the Detroit News, in his State of the City address in March, Mayor Duggan vowed that the Packard Plant would be redeveloped. He also said that the process would save the front portion of the city-owned building, along the south side of Grand. If that happens, it would be a win for both the city and for preservationists.

The plant, awaiting its fate, remains a bit of tourist attraction. The day I visited with a photographer, we were all alone with the ghosts, walking among trespassing signs, rubble, and trash. On the south side of the plant, in a doorway near a pile of bricks from a collapsed floor above, we found a tattered Look magazine, dated April 9, 1963. Its pages flapped back and forth in the breeze, much like the Packard plant’s fate has for years.

Zimmerman chooses to remain optimistic. “If you can rehab Fisher 21,” she says, “you can rehab Packard—at least some part of it. What these buildings have going for them is that they’re really hard to tear down; they’re so big and well-built. At this point, a lot of it may be too far gone and no longer structurally safe, but hopefully some of Packard can be saved.”

The clock is ticking. As always, in Detroit, the question is what happens when it stops.

Want more stories from our Great Reads project? Click here.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

The Old Buildings Have A lot of History of Americas Past with Many Photos of what America was All About ,

but now they are Like old Battle Ships , time to melt it Down , and Start New History

The central train station is such a cool building.

OUR TOWN HAS ABOUT A DOZEN OR MORE HISTORIC BUILDINGS LEFT, INCLUDING THE ORIGINAL SHAW-WALKER OFFICE FURNITURE BUILDING. PART OF IT HAS BEEN RAISED AND PART HAS BEEN TURNED INTO CONDOS. GOOD, NEW BUILDING SPACE IS A PROBLEM ALL OVER. AS I GO AROUND TOWN I REMEMBER A BUILDING OR TWO AND I THINK , WELL EVERYONE WHO WORKED HERE HAS DIED OR IS SO OLD IT DOESN’T MATTER, WHAT EVER HAPPENED THERE ISN’T GOING TO EVER HAPPEN HERE AGAIN. TAKE DOWN THE BRICKS, AND LEAVE THE MEMORIES.