Media | Articles

How BMW’s towering “Four-Cylinder” HQ almost never happened

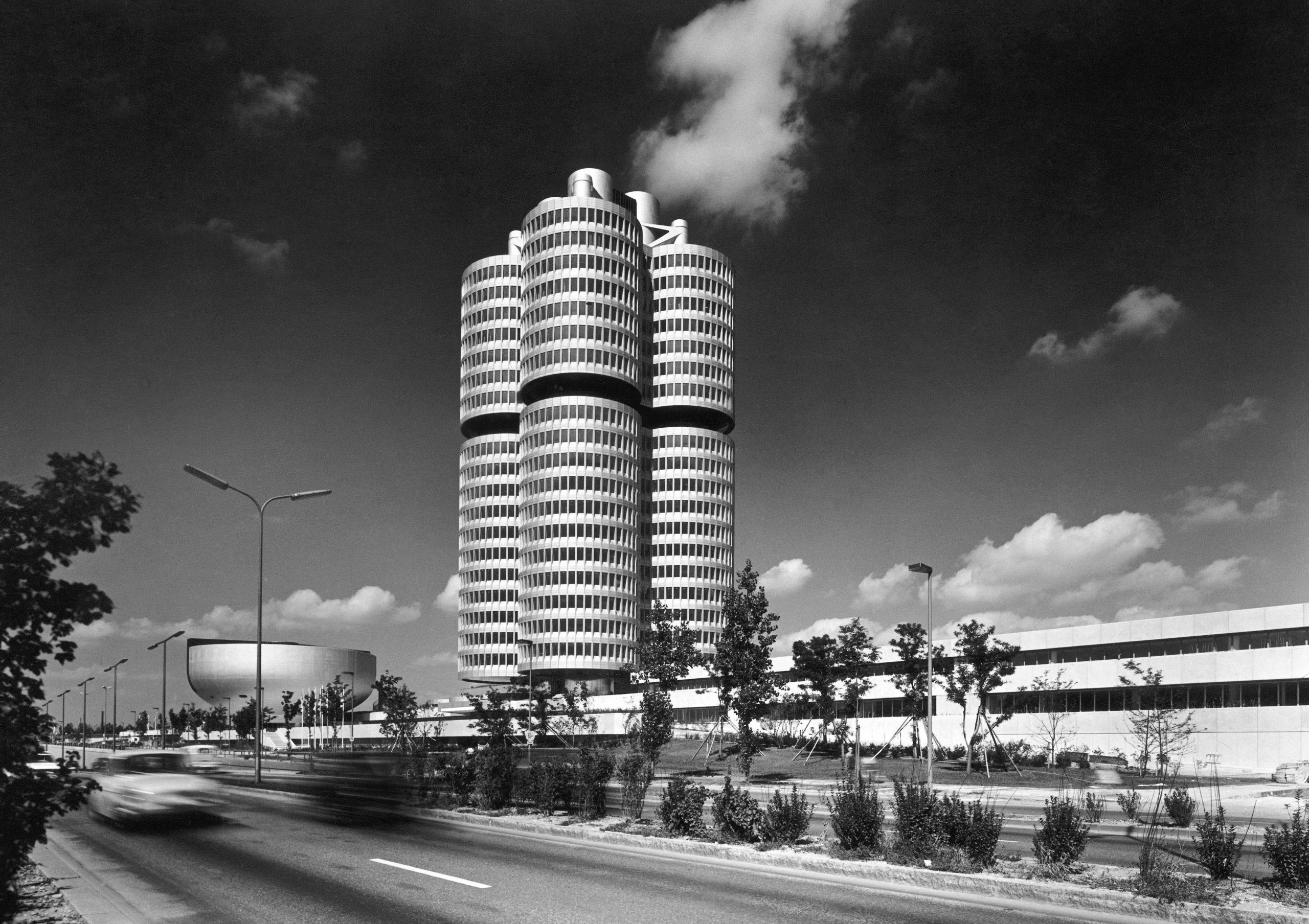

Any motoring enthusiast who’s visited the home of Bayerische Motoren Werke has surely made a point to visit the Vierzylinder, BMW’s quadruple-towered headquarters. Looming 330 feet in Munich’s northwest skyline, the “Four-Cylinder” sits just across a footbridge from the BMW Welt, the company’s flagship showroom where more than three million pilgrims worship at the temple of sheet metal and glass.

Breaking ground in 1968 and opening in 1972, the BMW tower was an architectural marvel of its time. Instead of standing on a more conventional resting foundation, all 22 floors hang from a series of cantilevers and central supports. It’s a structural approach more akin to a suspension bridge than an office building. The cloverleaf-shaped floor plan, designed by Viennese architect Karl Schwanzer, offers open, circular spaces originally meant to enhance collaboration and productivity among workers. This year marks the structure’s 50th anniversary.

In the late 1960s, however, the company was not yet the automotive powerhouse that Germany—and the rest of the world—later came to know. Not even a decade earlier, BMW had narrowly escaped acquisition by Daimler-Benz after the prohibitively expensive 507 roadster took the Bavarian company to the brink of financial ruin. (Examples now fetch $5 million at auction.) After shareholder Herbert Quandt rescued the business, BMW finally found its footing with the 02 series—a range of small, affordable, fun-to-drive cars based on a shortened version of Wilhelm Hofmeister’s Neue Klasse sedans.

Against this backdrop, BMW needed space for its expanding operations in land-scarce urban Munich. It launched a design competition for a new facility who opening would coincide with two auspicious events. First was the 1972 founding of BMW Motorsport GmbH—aka BMW M—to spearhead the company’s racing program. Munich hosted its first Olympic games that same summer, with the festivities somewhat overshadowed by terrorist attacks that left 17 people dead. Nevertheless, the world’s gaze was on Munich and that attention symbolically welcomed Germany back into the international post-war community.

Schwanzer’s firm won the contract with its design for the tower, as well as a futuristic-looking parking structure and the adjacent, bowl-shaped BMW Museum. Although its shape resembling a four-cylinder engine—the configuration at the heart of the popular 2002—was not strictly intended by its designers, it nevertheless became a fitting representation for a company focused on engineering and precision. “It’s hard to imagine Munich without the Four-Cylinder,” says BMW Group’s former chief designer Chris Bangle.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The building, however, almost didn’t make it past the drawing board. In a new documentary about Schwanzer, He Flew Ahead, one of the architect’s former employees reveals how the tough but supportive boss would walk around after hours, fishing out discarded doodles from the wastebasket that the junior architects had drawn during brainstorming sessions. “We drew a cloverleaf just for fun and threw it away,” recalls one colleague. Schwanzer retrieved the paper from the trash and returned it to the young architect’s desk, along with the words “keep it up” written across the crumpled sketch.

A dynamic analysis of the BMW tower, published in 2016 by the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Sydney, notes that “The structural design of the BMW Tower represented a major challenge to Germany’s finest engineers because the suspended 99.5-[meter]-high structure had to withstand not only static loading, but large wind dynamic loading while having deflections within appropriate serviceability limits.” Although there were already a handful of examples of this type of suspended building around the world, none had ever been built to the height of Schwanzer’s design. When it was completed, the suspended portion of the tower weighed in at 16,800 tons.

The tower was technical achievement, and builders still managed to save money and time by using many pre-fabricated elements. The entire project was completed in only 26 months. The 21-story building consists of 18 office floors and four technical floors. Each cylinder contains a concrete shear core for stability as well as vertical ties and compression columns that run along the exterior façades. The indented level visible near the top third of the structure contains lattice girders made of reinforced concrete that transfer loads between the columns and the cables. BMW reference materials explain that the four cylindrical elements were initially constructed at ground level before being raised hydraulically and completed in several segments. Each cylinder was suspended from four giant “crane arms” positioned in the shape of a cross at the building’s central core. These can be seen at the top of the building today, visible on either side of the gargantuan BMW roundel logos, which, incidentally, were positioned perfectly in the line of sight for nearly every spectator and camera lens at the 1972 Olympic games. Despite this visual prompting the city of Munich to fine BMW 100,000 Deutsch Marks (about $52,300) for violating no-advertising laws, one imagines that this was chalked up as a huge marketing win.

In the mid-2000s, the Four-Cylinder experienced a significant renovation. Changes included replacing two of the elevator banks with a fire elevator. One former BMW employee claims psychologists were consulted on the redesign of certain interior spaces, which included deliberately making some conference rooms feel “uncomfortable.” However, current BMW spokespeople couldn’t confirm whether this was indeed the case.

Looking into the future, BMW is working on a plan to redesign its current Werk 1 factory site next to the Four-Cylinder building as it prepares to transition that assembly line from internal combustion engine-vehicles to its “New Class” electric platform slated for 2026. The master plan includes a transformation for old buildings into new structures that BMW spokespeople claim will focus on “openness and transparency as well as sustainability.” Expected to be completed by 2030, the reimagined campus will have spaces for recreation as well as work for its 7000 employees from 52 countries.

The Four-Cylinder continues to stand as a beacon of BMW’s corporate identity, even as that identity has evolved over the decades. It, along with the nearby Olympic Village, is an enduring symbol of Munich and continues to attract visitors from near and far. “The relationship between the park, the building, and everything works extremely well together,” Bangle observes. “It makes you proud to work at BMW.”

Schwanzer died in 1975, just three years after the Four-Cylinder was completed. He may not be around any more to rescue great ideas from the shredder, but his legacy—and BMW’s—lives on in that cluster of four towers.