Media | Articles

How automotive air conditioning went from miraculous to mundane

It was at exactly this time of year in the late 1970s when my family embarked on our longest-ever road trip from our home in New York state to visit relatives in Louisiana. We drove our Plymouth Satellite station wagon, which had the sticky summer combination of vinyl seats and no A/C. The trip took us four days, because by late afternoon my mother and my sister would be complaining so much that we’d have to stop driving and search for a motel with air conditioning and a pool.

When we finally arrived, I discovered that, although summers in New York were hot and humid, the liquid air of New Orleans was on another level entirely—particularly during the daily afternoon thundershowers when you couldn’t even roll down the windows.

Outfitted in engineer-spec (power steering and brakes, automatic, AM radio, and that’s about it), our ’73 Plymouth was a little behind the times, but not much. The modern miracle of air conditioning came first to commercial buildings, starting in the early years of the 20th century. Central air conditioning systems for private houses started to become available in the 1930s, although it was the arrival of mass-produced window A/C units in the late 1940s that first brought cooled air into most people’s homes.

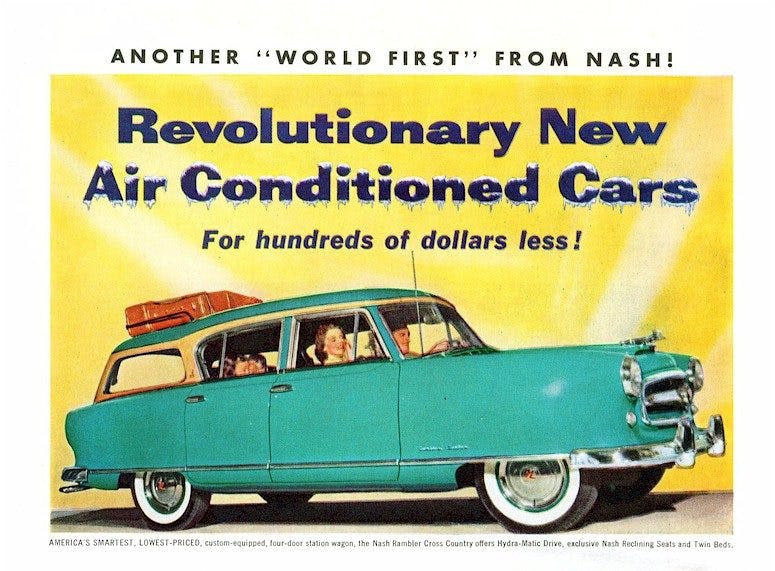

When it came to automobiles, Packard, Cadillac, and Imperial offered crude, trunk-mounted systems in a handful of vehicles just before World War II, but modern automotive A/C did not arrive until the mid ’50s. By 1958 the feature had spread to all major makes, but it was expensive ($446 on a ’58 Plymouth, for instance). In 1965, less than one-quarter of new cars were so equipped, but that figure rose steadily to more than 70 percent by 1973. The take rate reached nearly 99 percent by 1994—at that point, even the engineer dads were on board.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As a standard feature, however, A/C was adopted at a much slower rate, even at the high end of the industry. When Ford’s Continental Division (at the time, separate from Lincoln) introduced the new ultra-luxury Continental Mark II for 1956, the $10,000 automobile came standard with everything—except air conditioning, which was the sole option. The first car to make it standard was the competing Cadillac Eldorado Brougham, which arrived the following year.

A/C was still an option on most Cadillacs and Lincolns when the luxury-wannabe AMC Ambassador made the feature standard in 1968 and trumpeted that point in its advertising. Lincoln went to standard A/C for ’71. Chrysler’s Imperial followed in ’72 and Cadillac in ’75. For most brands, however, it was later—much later.

As recently as 2010, you could still get a sweatbox version of the Hyundai Accent and Elantra, Kia Forte and Rio, Nissan Versa and Frontier, Dodge Caliber, Jeep Wrangler, Chevy Aveo, Honda Civic, Mazda3, Mitsubishi Lancer, and Toyota Tacoma. During the 2010s, A/C finally became standard in even the cheapest cars as brands capitulated one-by-one.

The Tacoma pickup was the last holdout at Toyota; the bare-bones trim didn’t get A/C until 2011. The Dodge Caliber also cooled down with standard A/C in 2011. The Kia Forte added the feature as standard for 2011, while the Rio got it with its 2012 redesign. The 2011 Aveo was the last un-air-conditioned Chevrolet; the Sonic that replaced it for 2012 had A/C as standard. The base Nissan Versa also made the switch for 2012.

At Mazda, the low-budget 3 in SV trim finally came factory cooled in 2013. That same year, the Hyundai Accent and Elantra adopted the feature as standard, as did the Honda Civic. Mitsubishi dropped the Lancer DE after 2014, and the entry level for 2015 became the A/C-equipped ES. The Smart fortwo was a late holdout. It was 2015 when the base Smart fortwo Pure moved A/C from options list and onto its standard equipment sheet. The Nissan Frontier pickup had to wait all the way until 2018.

While the last of the miser-trim economy cars and pickups joined the air-conditioned era in the 2010s, at the far opposite end of the automotive spectrum, a counter-trend was developing. Super-sports cars deleted air conditioning for weight savings on track-focused, limited-edition models. McLaren has seen more examples of this configuration than most, with such cars as the 600LT, the 675LT, and the Senna. In all cases, McLaren customers can choose to add air conditioning back in at no cost—and one suspects that most do.

Outside of those hardcore supercars, there is one final holdout sold today in the U.S. without air conditioning. Can you guess? It’s the Jeep Wrangler Sport two-door. Unlike our old Satellite wagon, however, it offers relief from the heat in the form of a removable roof and doors. Even so, I’m not sure I’d want to drive one from New York to New Orleans in July.