Media | Articles

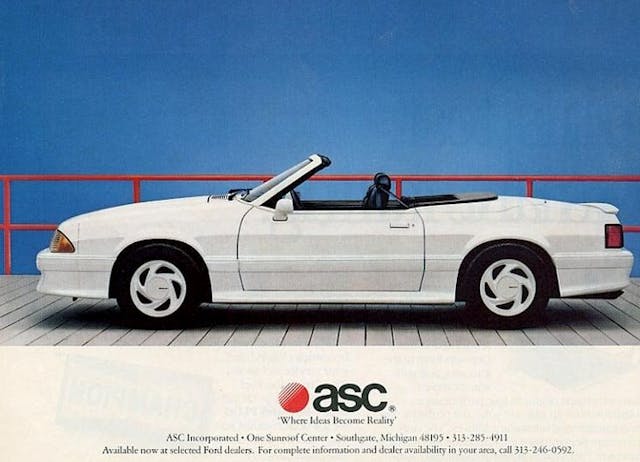

How ASC brought convertibles back from the dead

A funny thing started to happen when the American auto industry moved from the go-go ’60s into the uncertain ’70s. Over the course of the decade, Detroit’s Big Three seemingly lost the will to build convertibles.

In reality, the downfall of the American drop-top was deliberate and strategic. During the five-year period following their 1965 U.S. sales peak, convertibles plummeted in popularity, felled by increasingly affordable air conditioning in fixed-roof models, the popularity of sunroofs, and the rising frustration of owners tired of dealing with noisy, leaky, fussy tops that often needed repair or replacement within a few years from new.

Unwilling to invest in a slice of the industry that had dwindled to a mere two or three percent of total business, Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors began to slowly excise open-air models from their lineups, starting with full-size machines and moving down gradually to their smaller siblings. This cull was accelerated by the fear of toothier regulations regarding rollover safety, a specter dangled by the federal government. Many in the industry feared such regulations would make it impossible to build a compliant convertible.

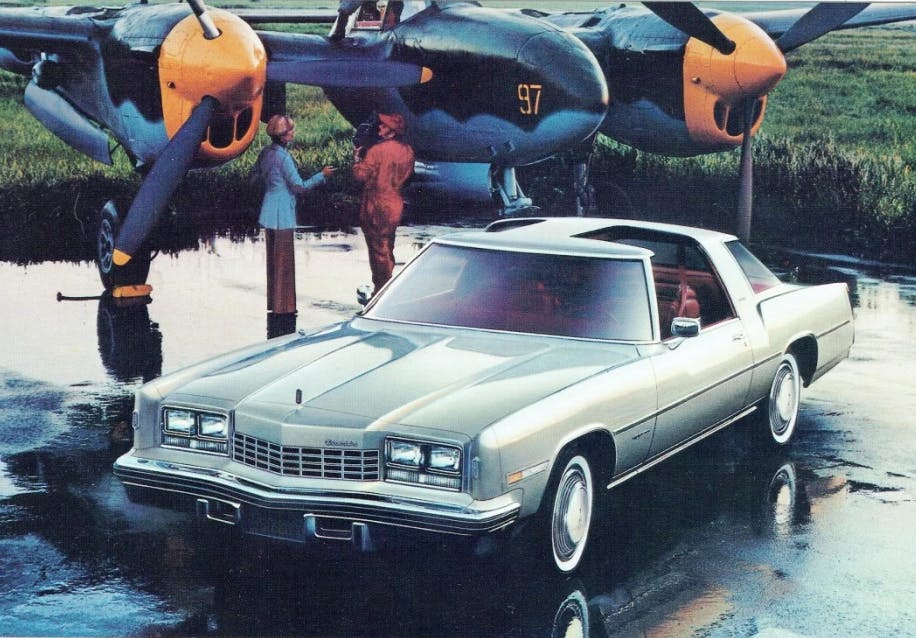

By 1976, the final American-built convertible of the era—the Cadillac Eldorado—had rolled out of the factory and into the garages of nearly 14,000 collectors. These enthusiasts were confident they had just purchased the last of a dying breed, and for a time they were right on the money. Automotive designers and product planners alike left ‘verts in the rearview, turning their backs decades of history.

Then, hope. Out of nowhere, it seemed, convertibles made a stunning comeback in the early 1980s after a nearly six-year absence from the nation’s highways. Standing at the forefront of this renaissance were three letters—ASC—representing the company responsible for reviving America’s love for windblown hair and scalp-searing sunburns.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

From sunroofs to no roofs

The roofless rejuvenation spearheaded by the American Sunroof Company (ASC) didn’t arrive without a hint of irony. After all, ASC was both an accelerant of the convertible’s demise as well as the spark for its resurrection.

First, some context. Heinz Prechter, who founded ASC in 1965, had democratized sunroof access as both an in-house option (starting with the Mercury Cougar in 1967) as well as an aftermarket addition, but that accomplishment did not scrape the surface of his ambition. By 1975, ASC had expanded its coachbuilding operations, producing limousines, wagon conversions, and unusual “custom” interpretations of various Cadillac models. It also jumped in on the T-top craze, standing alongside Hurst and Fisher as a purveyor of open-air fun for models like the Ford Mustang II and the Chrysler Cordoba.

ASC had also experimented with building full-fledged convertibles of its own. “We were never worried about convertibles being legislated out,” explains Henry Huisman, who worked at American Sunroof in the 1970s and who is currently the keeper of the ASC/McLaren flame. “The demand just wasn’t there for convertibles like it used to be, and major automakers didn’t want to do large-scale production anymore. There was a niche for outside manufacturers to fill.”

And fill it, ASC did. After producing an unusual power-operated T-top design for the Oldsmobile Toronado XSR concept car in 1977 (that was ultimately not produced), ASC continued to make inroads at General Motors. It was with Buick that the company got its break into full-convertible conversion in 1981, first slicing the roofs off of a pair of Indy 500 pace cars based on the Regal platform, and then one year later snagging the contract to build the first official convertible from GM in more than six years: the 1982 Riviera.

Small-firm savvy, third-party revolution

“Building convertibles was cost-prohibitive, it slowed down the assembly line, and automakers at the time weren’t interested in that kind of hassle to sell only a handful of cars,” says Huisman. “It’s not so much that Detroit couldn’t build a convertible if it wanted to, but they had so many alternatives—sunroofs, moonroofs, targa tops, T-tops—that it was no longer on the menu in-house.”

Although coachbuilders like Griffith had recently produced targa-like interpretations of dealer-available cars like the AMC Eagle and the Toyota Celica Sunchaser, before the Riviera true drop-tops remained the exclusive province of staggeringly-expensive third-party conversions. Buick made for an interesting test case for getting mainstream American convertibles back on the road, and Heinz Prechter identified the Riviera as a well-styled vehicle suited for convertible duty. And, critically, GM could sell it at a price point justifying such a project’s extra expense.

ASC’s Riviera convertible prototype so impressed the automaker that it was incorporated into the lineup not as a specialty model, but rather as a full-fledged member of the Buick family. The arrangement was simple: Buick sent Rivieras to ASC’s shop in Lansing, Michigan, and the company shipped them back, sans-roof, so they could be sold at a startling $9000 premium over the cost of the base coupe. That’s a $26,220 mark-up in 2022 dollars.

Making the Riviera the most expensive model in the entire GM portfolio might have seemed an unusual strategy, but it was an instant success. In short order, Chevrolet, Pontiac, and Cadillac were all knocking on ASC’s door for convertible versions of vehicles like the Cavalier, the Sunfire, and the Eldorado. International suitors soon began turning up for small outfit’s expertise. Prechter took the design lead on Saab’s convertible version of the ultra-popular 900, which incorporated more than a little of his company’s Riviera-derived know-how (as well as a number of the same parts). The Saab project was followed by requests from both Nissan and Toyota to perform similar surgery on models like the 300ZX and Paseo.

The early-’80s convertible whirlwind was entirely dominated by third-party companies eager to exploit the apparent delta between renewed demand for convertibles and Detroit’s reluctance to devote any internal resources to their production. The same year the Riviera hit, Chrysler tagged in Creative Industries to build a convertible version of its wood-laden LeBaron K-car, followed a year later by Ford outsourcing the Fox-body Mustang to Cars & Concepts for the same treatment.

A legacy of excellence

Above all of these contenders, however, ASC looms large. Over the course of the next 20 years, Prechter’s company had a hand in the design and execution of convertible versions of the Chevrolet Camaro, Porsche 944, Buick Reatta, Infiniti M30, Dodge Dakota, Mitsubishi 3000GT, Mitsubishi Eclipse, Chevrolet SSR, Toyota Solara, and both the BMW Z3 and Z4. These are merely the highlights of the dozens of models whose owners were shown the light of day by way of ASC’s convertible prowess.

“ASC definitely moved quality up a notch,” says Huisman. “It produced higher-quality tops compared to the older, mass-produced designs, thanks in part to the lower production numbers. It also introduced the retractable hardtop.”

Interest in convertibles peaked in the 1990s, during the NA Miata’s heyday, when models like the Mustang (whose production had been returned to Dearborn) counted on ragtops as an important sales pillar. Today’s convertibles once again represent a diminished niche of the auto industry; the Mustang and Camaro are the only ones left from America’s brands. Still, they never went away entirely like they did after 1976, and for that we can point to ASC’s Riviera-led explosion of coachbuilt convertibles as a major reason why American motorists have been able to enjoy 40 straight years of fun in the sun.

Pretty sure Corvette is available in convertible spec as well.