Media | Articles

How a woman and a Jewish racing driver beat Hitler in 1938

In May of 1940, soon after the German army overran and occupied France, a Gestapo officer visited the headquarters of the Automobile Club de France on the Place de la Concorde in Paris. He demanded that the club’s librarian bring him the records for races sanctioned by the club. As his subordinates carted off the record books, he dismissed the librarian, saying, “We will write the history now.”

Consensus holds that Nazis wanted to rewrite a particular piece of racing history, an embarrassing break in Germany’s state-supported teams’ dominance of Grand Prix Racing in the 1930s. The Silver Arrow cars campaigned by Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union had to remain the übercars, according to the Nazi narrative. The Gestapo wouldn’t stop at paper records, either; according to rumor, the Gestapo was also trying to locate and destroy the very cars that disgraced the Reich in one of motorsports’ great underdog victories.

Fortunately, the Nazis’ revisionary attempt failed, and the truth prevailed. The Silver Arrows’ defeat has now been ably documented by New York Times-bestselling author Neal Bascomb, in his book Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, 2020).

Bascomb, who traveled the world exploring private archives and experiencing 90-year-old vintage race cars firsthand to research the book, has done a remarkable job; in addition to documenting in great detail the pre-war Grand Prix scene, Bascomb has captured the flavor of the era and the larger-than-life personalities that inhabited it.

African-American track and field star Jesse Owens winning four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Olympics refuted Nazi notions of Aryan racial superiority at those competitions, but Owens’ victories were not entirely unexpected. Owens had already established himself as a world-class athlete, setting track and field records in America before the ’36 Olympics. On the other hand, when René Dreyfus sat on the grid for the 1938 Pau Grand Prix, in a Delahaye 145, few gave him a chance at winning—but Dreyfus, whose father was Jewish, would also put the lie to the Nazi narrative.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Dreyfus had a notable racing record and could boast Grand Prix victories with Alfa Romeo (then headed by Enzo Ferrari) and the Maserati brothers on his resume. He competed against legendary racers like Ascari, Caracciola, and Nuvolari but in 1936, he hadn’t had a competitive ride in years.

By the later half of the 1930s, Grand Prix racing had become intertwined with international politics. The German racing teams received substantial financial support from the Nazi regime and their parent companies aimed to turn profits making military material for the Reich. While René did not identify religiously as a Jew, there was simply no way that Mercedes or Auto Union would put someone with Jewish blood and a Jewish surname behind the wheel of race cars intended to demonstrate Aryan superiority. Nationalism in Mussolini’s fascist Italy meant that Dreyfus, a native of France, also could not get a ride at Alfa or Maserati.

Today, we know Delahaye as a French marque that made beautiful Art Deco roadsters and coupes and folded in the mid-1950s; but, if weren’t for a rewarding foray into racing, Delahaye might never have survived that long. In the early 1930s, the company made staid sedans and a line of commercial vehicles, neither of which were selling particularly well. With a worldwide economic depression in full swing, difficult decisions loomed.

The company was then owned by Marguerite Desmarais and her brother Georges Morane. Together with Desmarais’ late husband, Morane had bought the company from its founder in the late 19th century. In 1932, Delahaye’s manager, Charles Weiffenbach, presented the owners with two paths forward: drastically expanding midrange passenger vehicle production to compete with Citroen, Peugeot, and Renault, something that would require a substantial investment; or dropping the passenger cars altogether and concentrating on commercial vehicles. Neither option was guaranteed to save the company.

Madame Desmarais surprised Weiffenbach by offering a third proposal: “If you can’t build automobiles in quantity, build fewer but better ones. Win races to make the marque better-known and to sell more luxurious and expensive cars.”

Weiffenbach assigned engineer Jean Francois the task of turning Delahaye into a performance brand. Francois designed a lightweight chassis that boasted independent front suspension, a first for Delahaye, and a 3.2-liter straight-six gasoline engine based on one of the company’s truck engines. That choice of a reliable truck engine was deliberate, based on the need of race cars to run at full throttle for extended periods of time. Testing at an average speed of 100 mph over 500 miles on the high-speed, banked Montlhéry autodrome proved the design was worthy.

At the 1933 Paris Salon de l’Automobile, Delahaye introduced two new luxurious and fast models based on the test car, each clothed in a sweeping coachbuilt body. There was the short-wheelbase, 2.1-liter four-cylinder 134, and the larger 138, with the 3.2-liter six. The new models were a hit and put Delahaye on firmer financial ground.

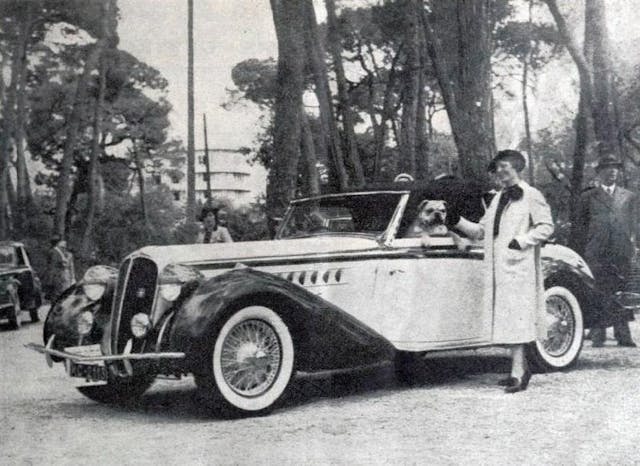

While one woman made it possible for Delahaye to get into performance cars and racing, it was another woman to put those cars on the track. Lucy O’Reilly Schell was a wealthy American expatriate heiress, whose husband Laury also possessed considerable worldly means. They lived in the Paris suburbs with their two sons and Lucy’s beloved bulldog. The Schells competed, fairly successfully, in a number of international rallies, including the Monte Carlo rally.

Though not as well known today as some other female automotive pioneers like Alice Ramsey, Dorothy Levitt, and Hellé Nice, Lucy was one of the best female drivers of her era. More impressively, she remains the only woman to own a winning Grand Prix racing team.

The Schells approached Weiffenbach with the idea of going rallying in a short-wheelbase 134 powered by the bigger six-cylinder engine. That concept became the Delahaye 135. While they never won a rally outright in the cars, the Schells rallied Delahayes until a bad accident convinced Lucy to retire from competition. She didn’t leave racing, though.

For much of the 1930s, the polished aluminum-bodied cars from Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union, nicknamed the “Silver Arrows,” traded Grand Prix victories. Although the two companies had radically different approaches, with Mercedes favoring traditional front-engine layouts and Auto Union, which hired Ferdinand Porsche as a consultant, using rear-engine (and later mid-engine) configurations, both teams were technically proficient. With government support, they also had the resources to effectively develop and campaign their race cars. At one point, Mercedes had about 300 people working for its Grand Prix racing team, including dedicated and trained pit crews.

In 1936, organizers proposed a new formula for the Grand Prix championship, with engine displacements limited to 4.5 liters for naturally aspirated engines and 3.5 liters for supercharged or turbocharged motors. While Delahaye had never previously competed at that ultimate level of motorsports, Lucy Schell approached “Monsieur Charles,” as Weiffenbach was known at Delahaye, with a deal he could not refuse.

Schell wanted to take on the Germans in Grand Prix racing, and she was willing to completely underwrite a Delahaye effort to create a competitive French team under her leadership. She wanted Weiffenbach to build her four race cars suitable for the Grand Prix events to race for her own team. That seems to have been an important point for Lucy, because some journalists had been dismissive of a female-owned racing team and often treated her rally team as the Delahaye factory crew.

Francois designed an all-new, 4.5-liter V-12 engine with a lightweight magnesium block for the new race car, which had a blunt, cigar-shaped body with a large hood scoop and aerodynamically shaped “motorcycle” fenders that could be removed, depending on the event.

When it came to picking a suitable driver, it appears that Schell had only one logical choice. Dreyfus was the most experienced and successful Grand Prix racer who, at the time, had no ride. He was also French. To give him some seat time in the Delahayes, Lucy had Dreyfus compete in the 1938 Monte Carlo rally and then Italy’s Mille Miglia, where he finished fourth despite having to repeatedly stop to top off a radiator, which was leaking from a puncture caused by a flying rock.

Coincidentally, embarrassed at the continued German success in auto racing, the French Popular Front political consortium had offered a million franc prize for the first French race car to average 146 km/h over 200 kilometers on the Montlhéry track. Though the competition was tilted somewhat in Bugatti’s favor, Dreyfus was able to exceed that mark in the newly completed 145, with just seconds to spare, just a day before the prize’s September 1, 1937 deadline. He wore his Dunlop tires down to the fabric cords in the effort. Weiffenbach split the prize with Lucy, who, in turn, gave Dreyfus half of her share.

To honor the French national racing colors, the four Delahaye 145 racers and the team transporter were painted in a lovely shade of blue, for Écurie Bleue, the team’s official name.

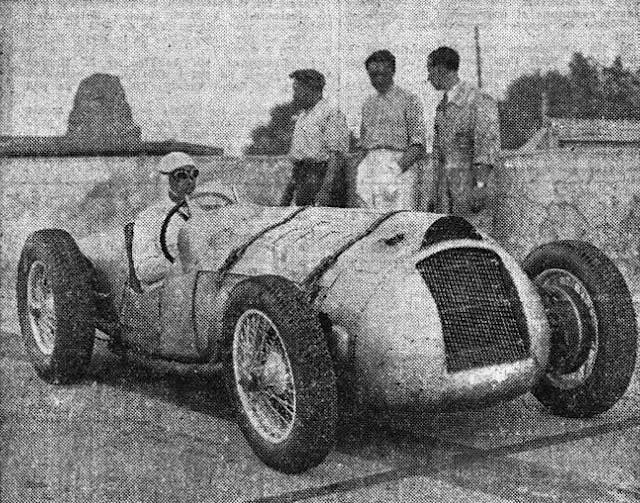

The first Grand Prix race with the new 145s was the 1938 Pau Grand Prix. Auto Union’s new mid-engine racer wasn’t quite ready, but Mercedes-Benz brought its new W154, designed by Rudolf Uhlenhaut, which had a substantial horsepower advantage over the Delahaye. Though Écurie Bleue was well-funded by Lucy, compared to Mercedes-Benz her team was a shoestring effort.

In practice and in qualifying, Dreyfus, however, noticed that Caracciola had a hard time controlling wheelspin from his W154 when accelerating out of corners; the Mercedes was overpowered for the course. The Pau Grand Prix was held on city streets, with tight corners and short straightaways, thus minimizing the Benz’s power advantage. That power advantage also came at the cost of a fuel burn rate of about 1.5 miles to the gallon. The Delahaye, however, could run the entire race without refueling.

Dreyfus’ strategy was to hang close to Caracciola until the W154 had to pit for fuel and then pull away. Dreyfus was able to pressure Caracciola so much early in the race—even swapping the lead position—that when Caracciola pitted for fuel, the German asked to be replaced by Hermann Lang, a reserve driver. (An earlier racing accident had left Caracciola with a severely damaged and painful leg. Much of the time he drove in pain, and most of the time he overcame that pain—but at Pau in 1938, he was dispirited by Dreyfus.) René finished ahead of Lang easily. Two weeks later, Dreyfus would go on to win the Cork Grand Prix in Ireland, but neither of the German teams competed in that race.

Surprisingly, Lucy Schell wasn’t at the scene of Écurie Bleue’s greatest victory; she was busy showing her award-winning Delahaye cabriolet by Chapron at the Cannes concours d’elegance.

Jean Francois designed a new car, the 155, for the 1939 racing season, but the car was not successful. Frustrated by French officials’ favoritism, which cut out Delahaye, Lucy switched to Maseratis, which also struggled to place. The German teams continued to dominate.

In September of 1939, soon after Germany invaded Poland, Lucy Schell and her husband Laury were seriously injured when their chauffeur collided with a van as they were being driven from Monaco to Paris. Laury died soon after. Lucy was heartbroken by his death and seems to have lost some interest in racing.

As the war approached France, Lucy used her influence to have Dreyfus exempted from military service so he could drive in the 1940 Indianapolis 500, where he finished 10th in relief of René Le Bègue. (It’s possible that Schell was more concerned about getting Dreyfus out of Europe than representing France in the race, because she later convinced her friend and driver to stay in America.) Dreyfus first started working at a restaurant and then enlisted in the U.S. Army where he served as an interpreter after the invasion of Italy. After the war, Dreyfus started another Manhattan eatery, Le Chanticlair, with his brother and sister, who had survived the Nazi occupation of France. The restaurant became an unofficial club house for much of the international racing community.

Whether or not the Gestapo hopied to destroy the car that embarrassed them, it appears that’s what the French automotive community anticipated. When Lucy Schell was done with her four 145s, she sold them, with Weiffenbach apparently handling the sales. The cars ended up at the shop of coachbuilder Henri Chapron, who dispatched two of them far from Paris, where they were hidden in barns and caves for the war’s duration. He disassembled the other two, scattering the parts around his shop.

After the war, Chapron reassembled and rebodied those two 145s with Art Deco designs. The cars changed hands a number of times until they were both acquired by Peter Mullin for his incomparable collection of classic French cars. One of the two remaining 145s hidden in the countryside was rebodied as a roadster by Franay and eventually acquired by New Jersey collector Sam Mann.

As for the provenance of the fourth Delahaye 145, it was raced after World War II, but then spent decades sitting abandoned under the banked track at Montlhéry, missing the front two-thirds of its body. In 1987 Mullin and his partner Jim Hull negotiated its purchase for $150,000, after which it underwent a three-year restoration to the specification in which it ran the 1938 Pau Grand Prix.

Mann and Mullin have a good-natured rivalry as to who owns the actual car that Dreyfus drove to victories at Pau and in the “Million Franc” competition. They both have documentation and experts to argue their cases, though Mann concedes that Mullin’s car may have the stronger case. In reality, though, race teams swap parts on their cars all the time, so it’s just as likely that each collector owns parts of the “Million Franc” car that took on the Nazis and won.

Bascomb has done a commendable job with Faster. He could have focused exclusively on Dreyfus and Schell’s success at Pau in 1938 and it would have made a compelling story. Instead, he took a deeper dive into the subject and produced a comprehensive look at the European racing scene of the 1930s—the racers, the cars, the engineers, and the political intrigue as well. Documented to an academic level with 40 pages of endnotes, Faster will likely become a reference source for automotive historians for years to come. Some reviewers have quibbled with Bascomb’s nearly lap-by-lap detail of a decade of racing, but his focus on the personalities of Schell and Dreyfus and their competitors behind the wheel, behind the drafting tables, and behind the political scenes keeps the book an entertaining and engaging read. We highly recommend it.