Media | Articles

Harley Earl’s GM styling team illustrated a pilot training manual in WWII—and it’s brilliant

We’ve seen an influx of creativity from the American automobile industry in the fight against COVID-19. Ford Motor Company repurposed fans normally used to ventilate F-150 seats to build powered air-purifying respirators. General Motors converted an automotive factory to produce medical ventilators. All sorts of automotive vendors have reassigned workers and repurposed equipment to manufacture the personal protective equipment (PPE) that keeps medical personnel and first responders safe.

This isn’t the first time the minds and machinery of the U.S. auto industry have adapted in times of crisis, however. In WWII, alongside dozens of other industries, automakers helped to comprise “The Arsenal of Democracy.” Franklin D. Roosevelt popularized the nickname during a wartime radio broadcast to commemorate how America’s industrial might switched, seemingly overnight, from manufacturing consumer goods to supplying wartime needs. Though the battle of today involves a microscopic enemy, American automakers’ recent switch from vehicles to ventilators has put the term back in circulation.

Similar to today, when PPE manufactured in the states is shipped globally, the transformed automotive industry of WWII supplied far more than just the U.S.—wartime supplies went to Great Britain and Russia as well. Though automotive manufacturers have recently adapted to medical needs, in some cases forgoing vehicles entirely, mobility was paramount in WWII. American automakers answered the call. A small, financially struggling company called American Bantam produced a preliminary design for what would become the Jeep. Ford famously ramped up production of heavy bombers to the point of producing one B-24 Liberator every 55 minutes at the Willow Run plant. Some older Russians still refer to medium-duty trucks as “Studebakers,” in homage to the fleets of U.S.-built trucks that roamed supply routes.

Everybody, it seems, did their part—and not just engineers and assembly line workers. Car designer Alex Tremulis, today known for designing the ingenious Tucker 48, spent the war years drafting advanced concepts for the United States Army Air Corps, one of which is today considered a predecessor to the Space Shuttle. Art Ross, who headed Cadillac and Oldsmobile styling in the ’40s and ’50s, drew tank destroyers during the war.

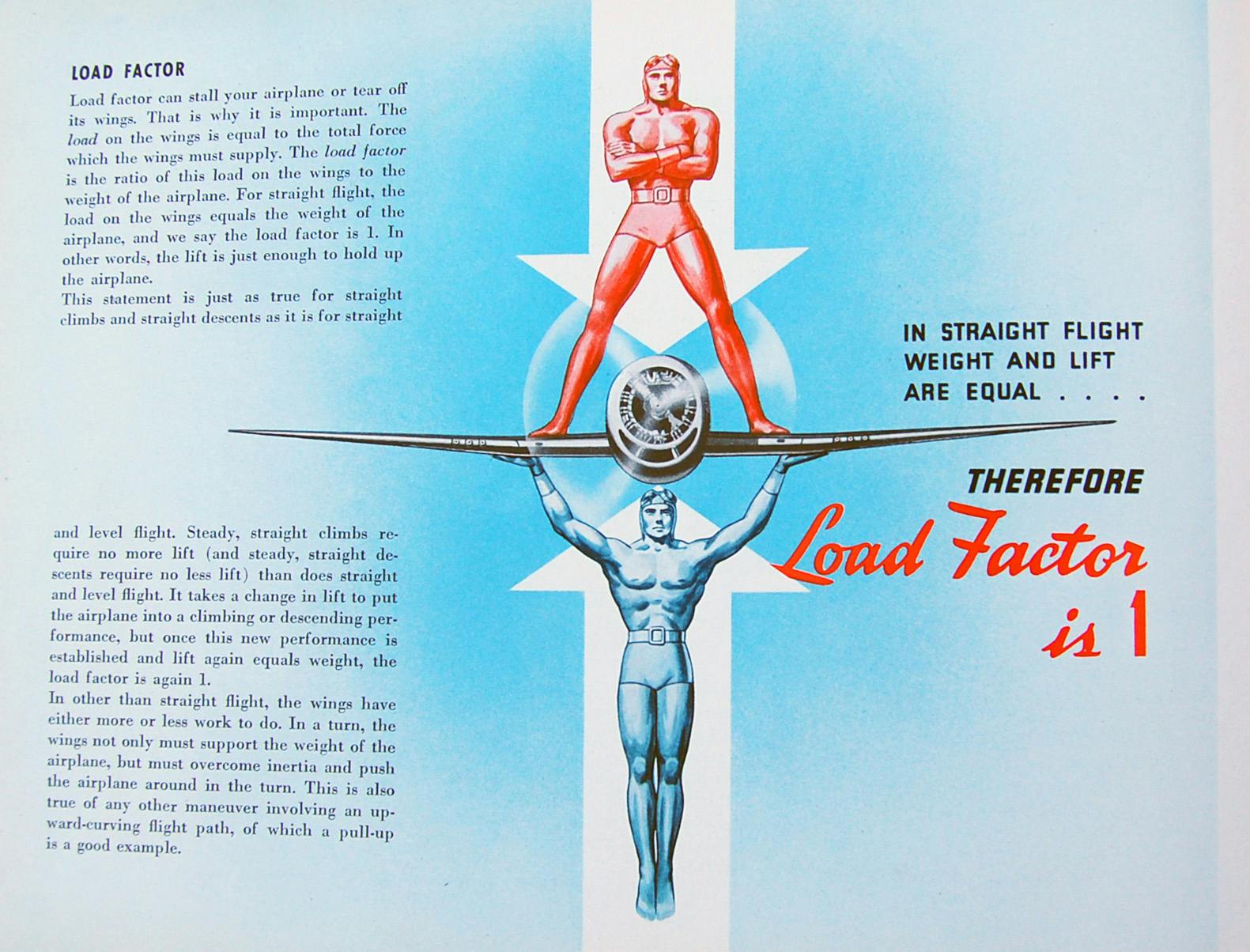

Over at General Motors, Harley Earl’s Graphic Engineering team drew designs that, unlike those of Tremulis and Ross, would never evolve beyond the printed page. However, the 1945 pilot training manual Flight Thru Instruments, illustrated by GM’s design department, is perhaps the pinnacle WWII contribution of General Motors stylists.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

First, some context. One advantage the United States had during World War II, particularly in the Pacific theater, was the ability to train pilots. Experienced American pilots would be periodically rotated back stateside to train novice pilots in the latest combat-proven strategies and tactics. After the Japanese lost about 400 pilots and their carriers at Midway, America’s ability to quickly develop its talent pool became decisive.

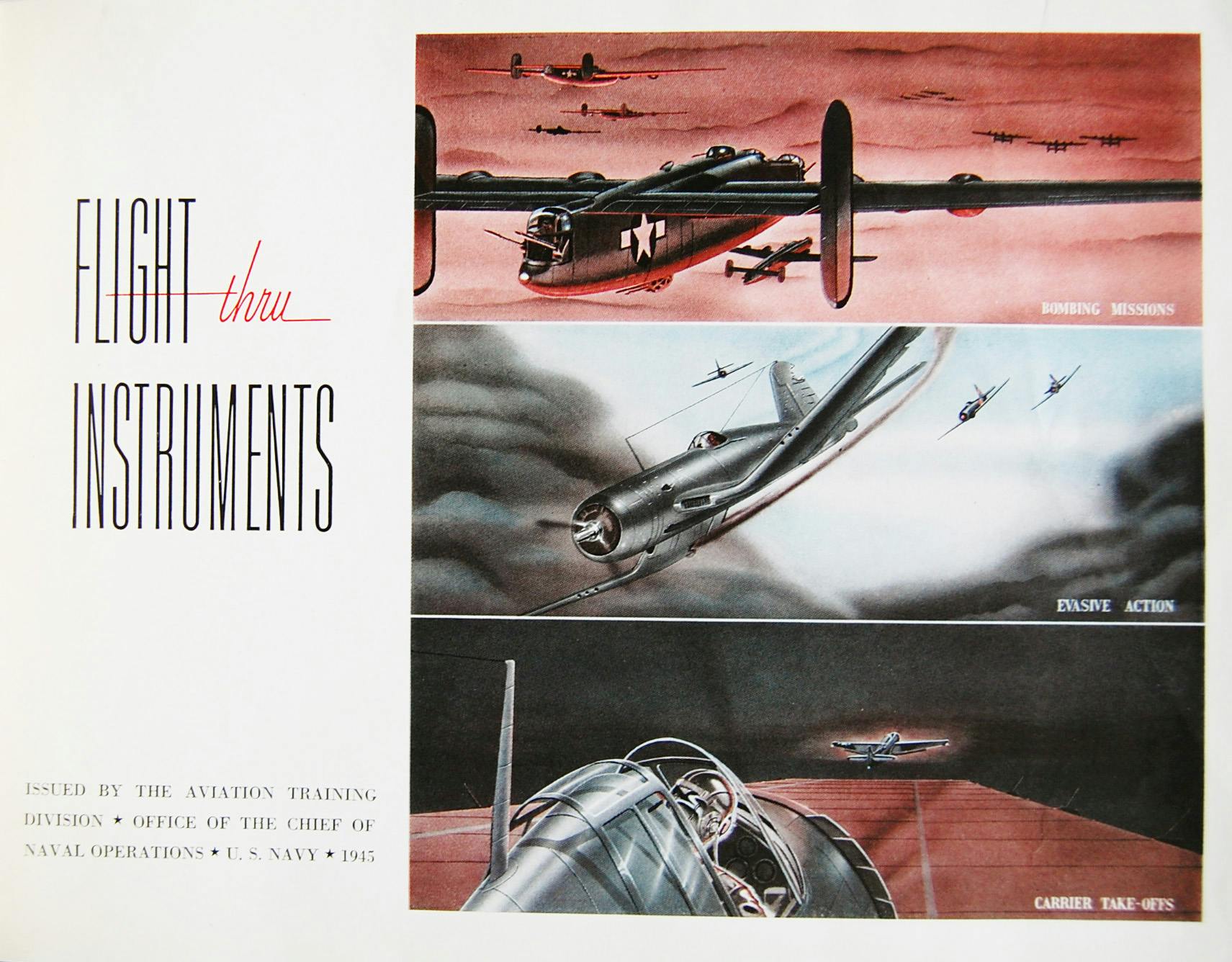

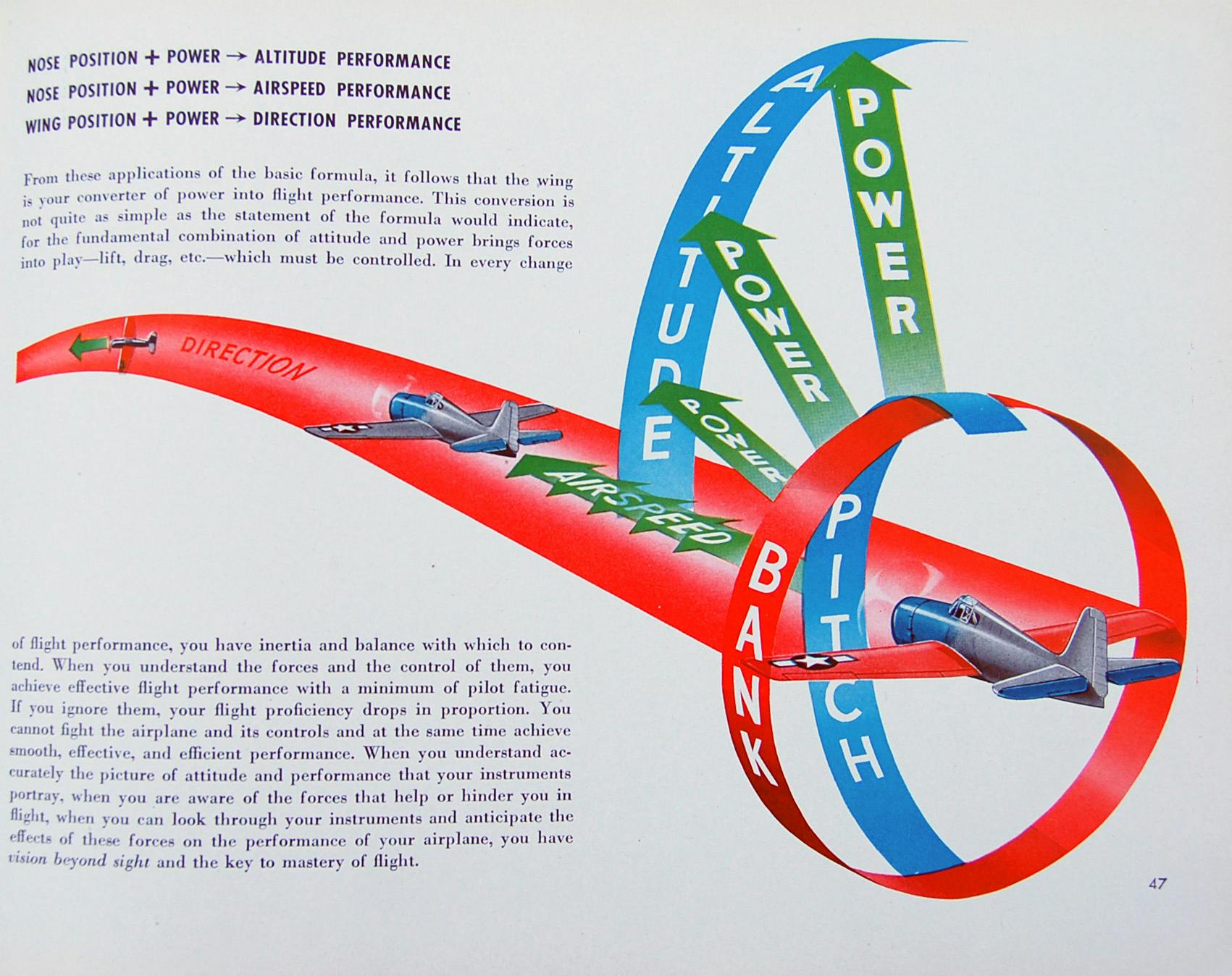

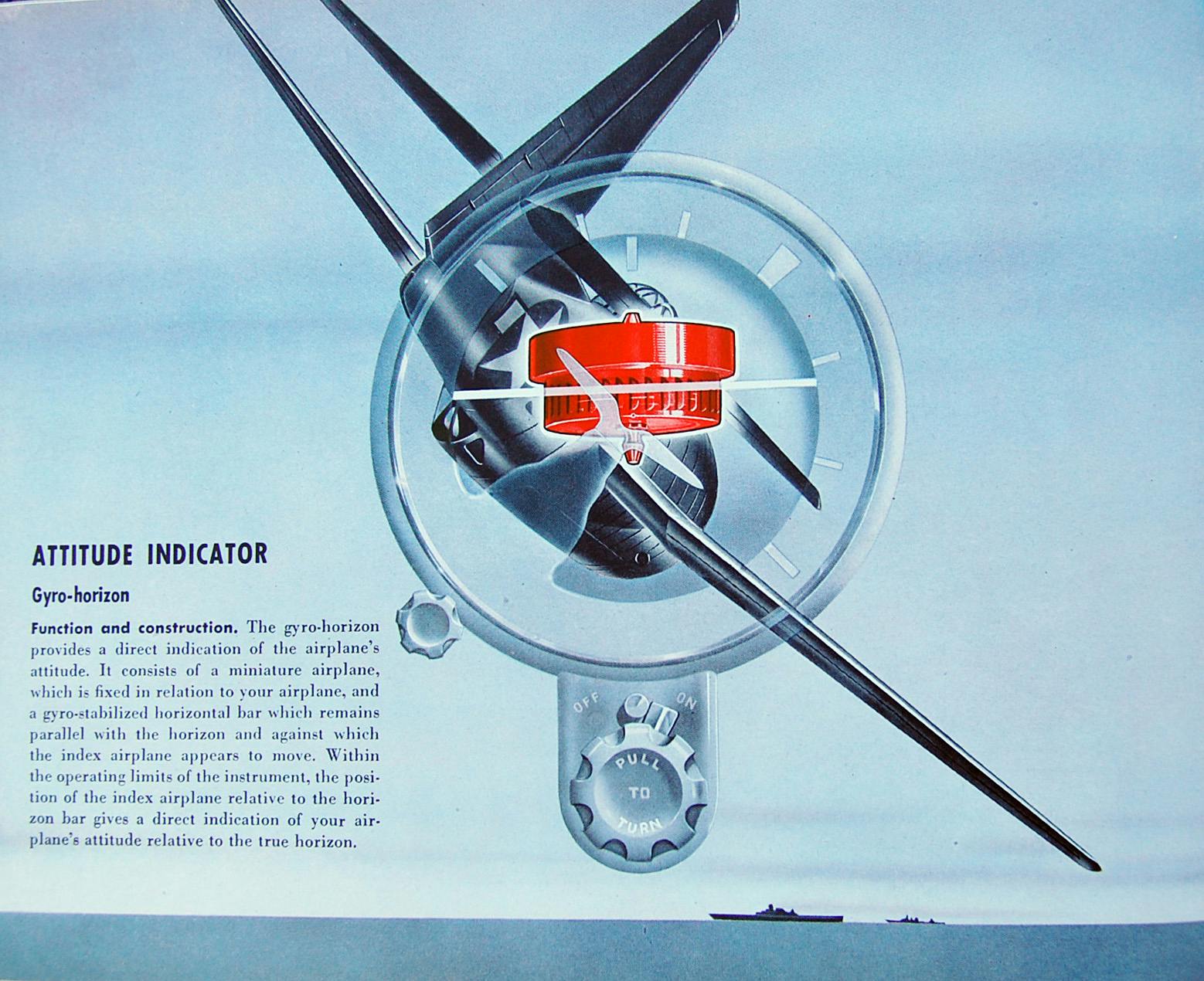

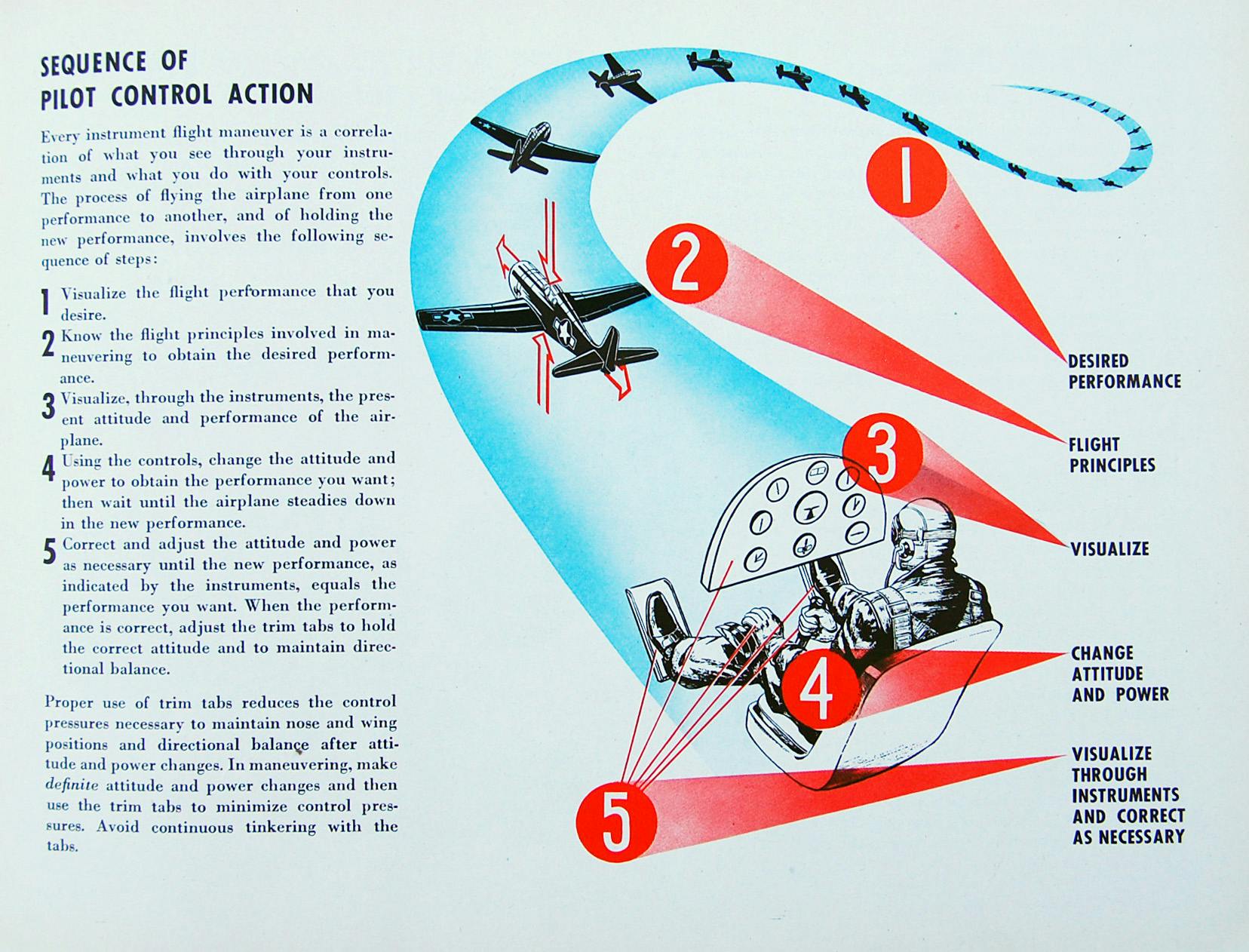

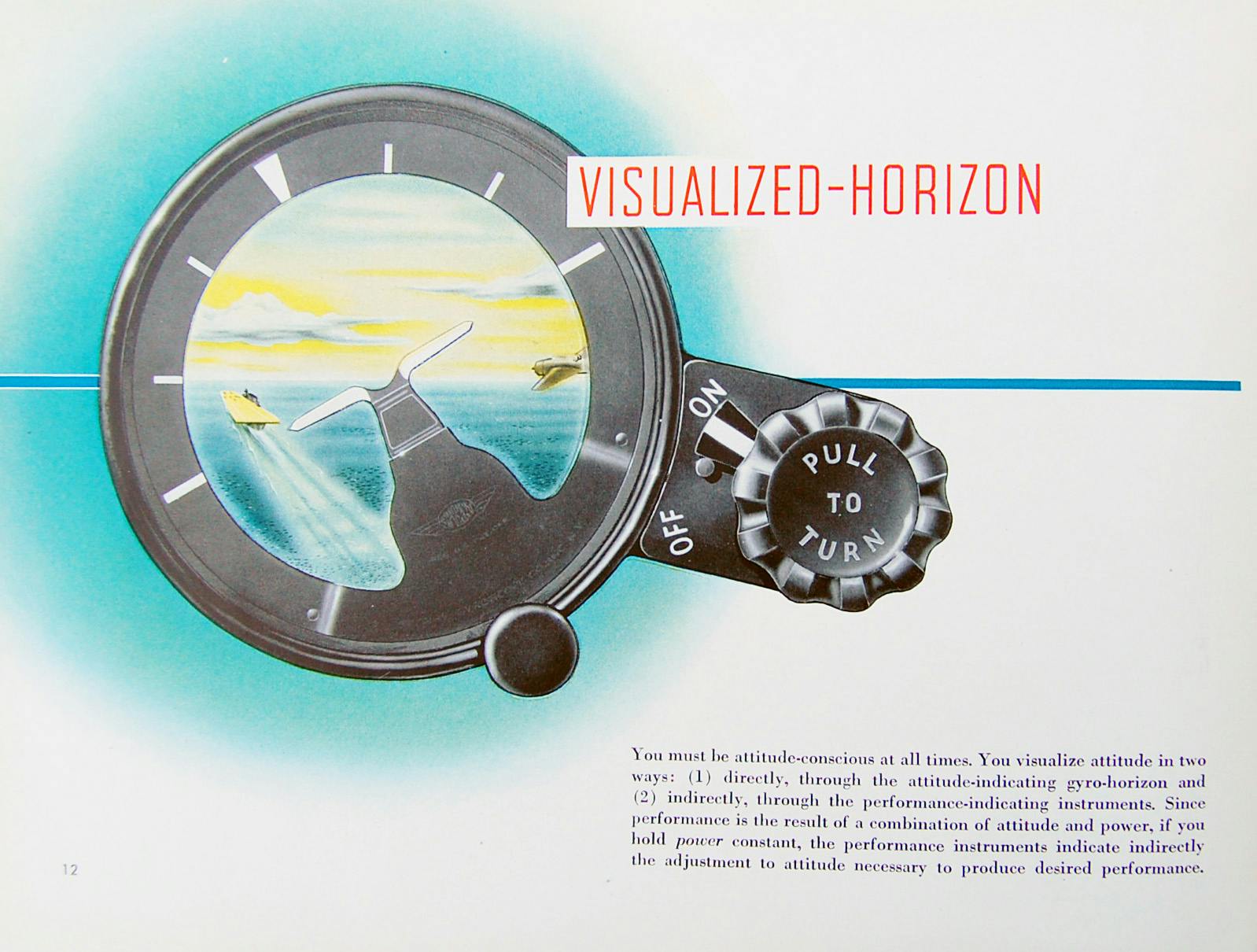

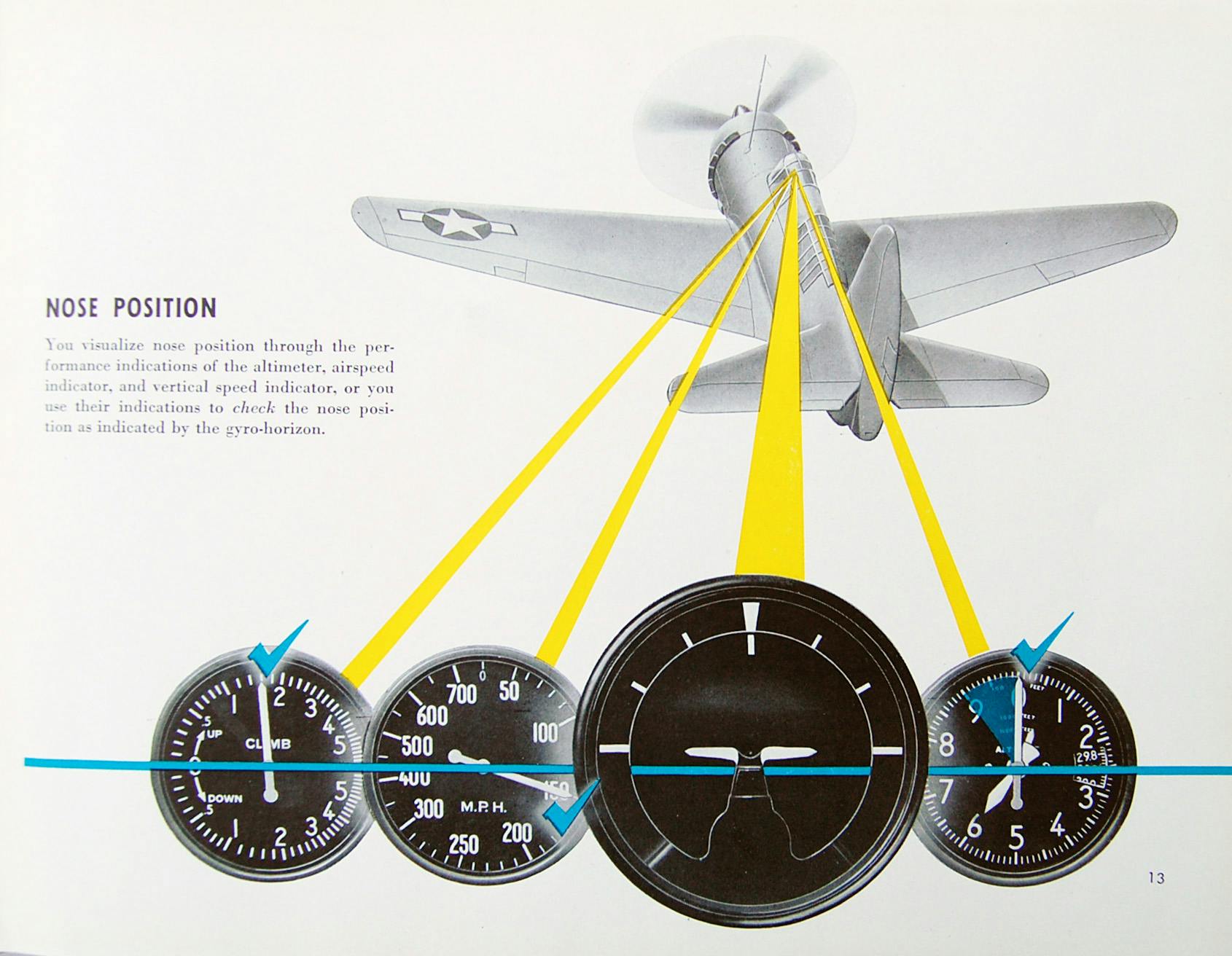

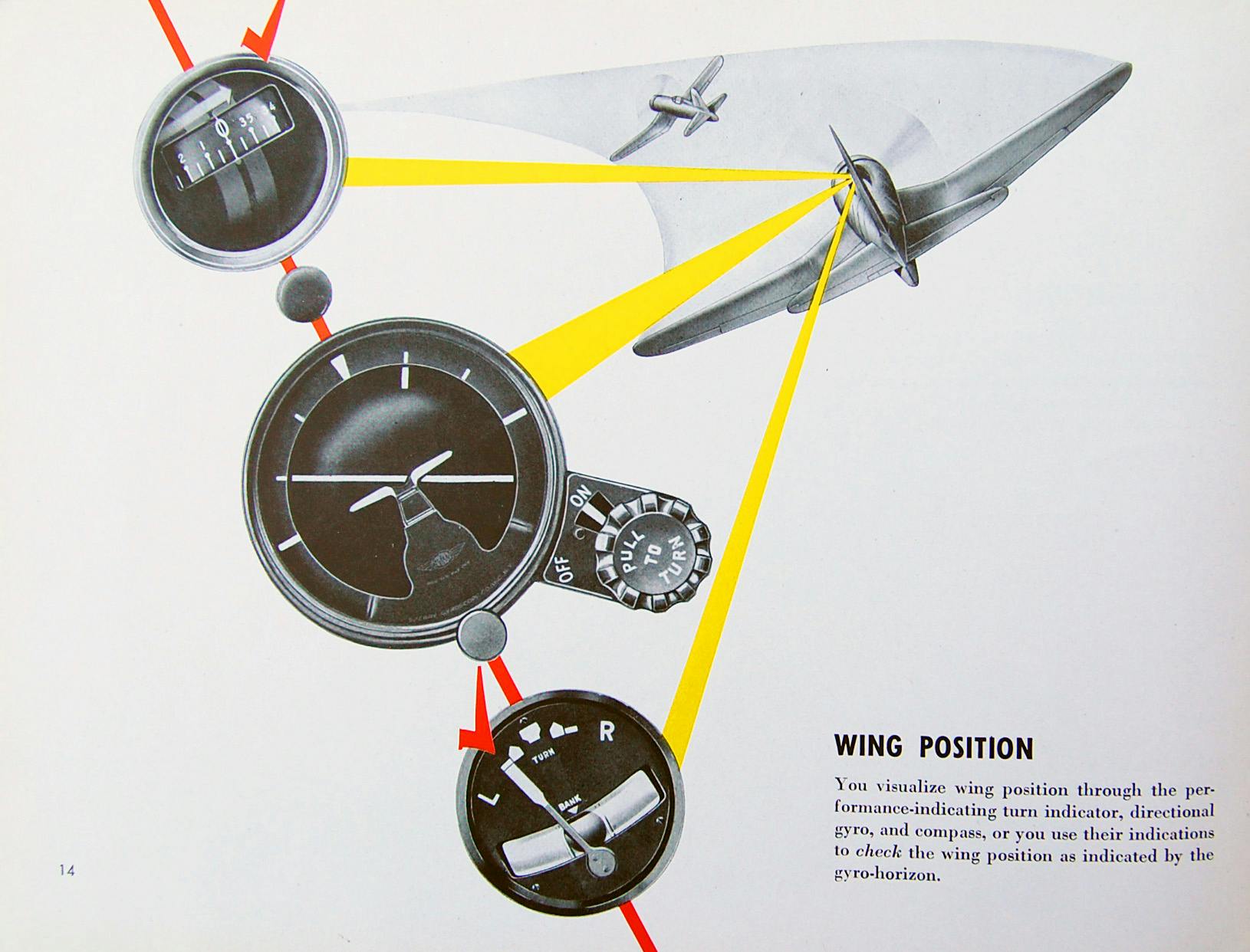

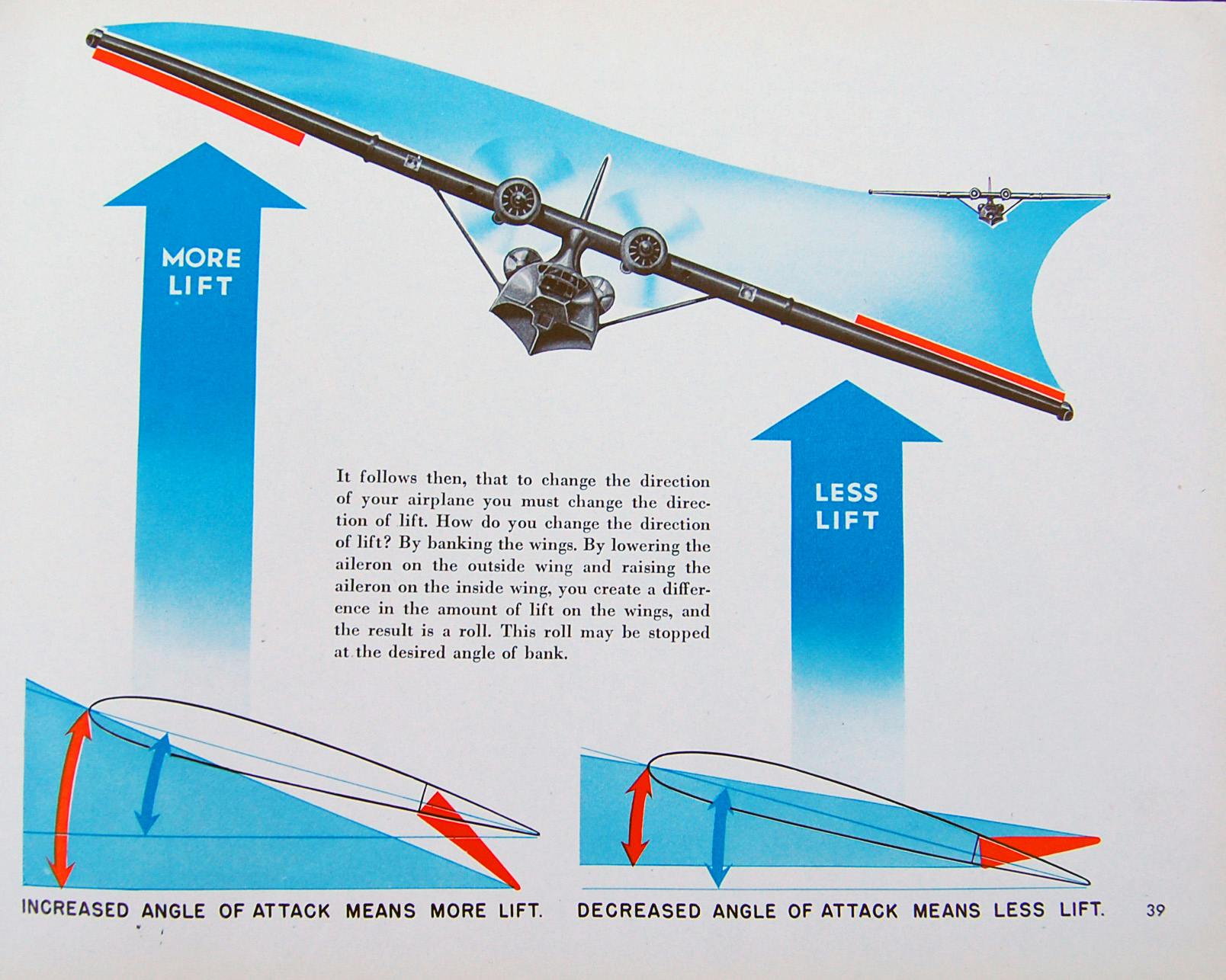

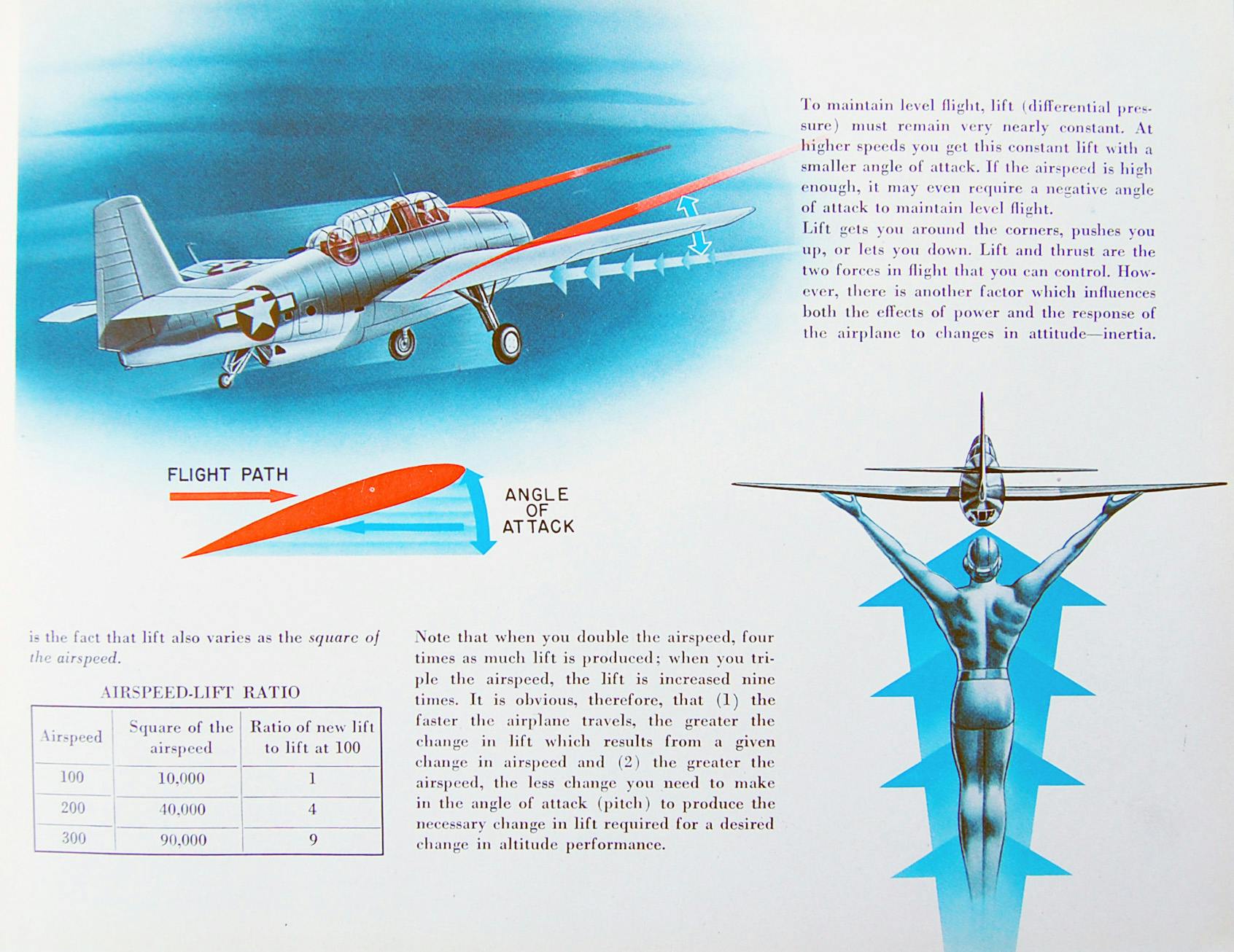

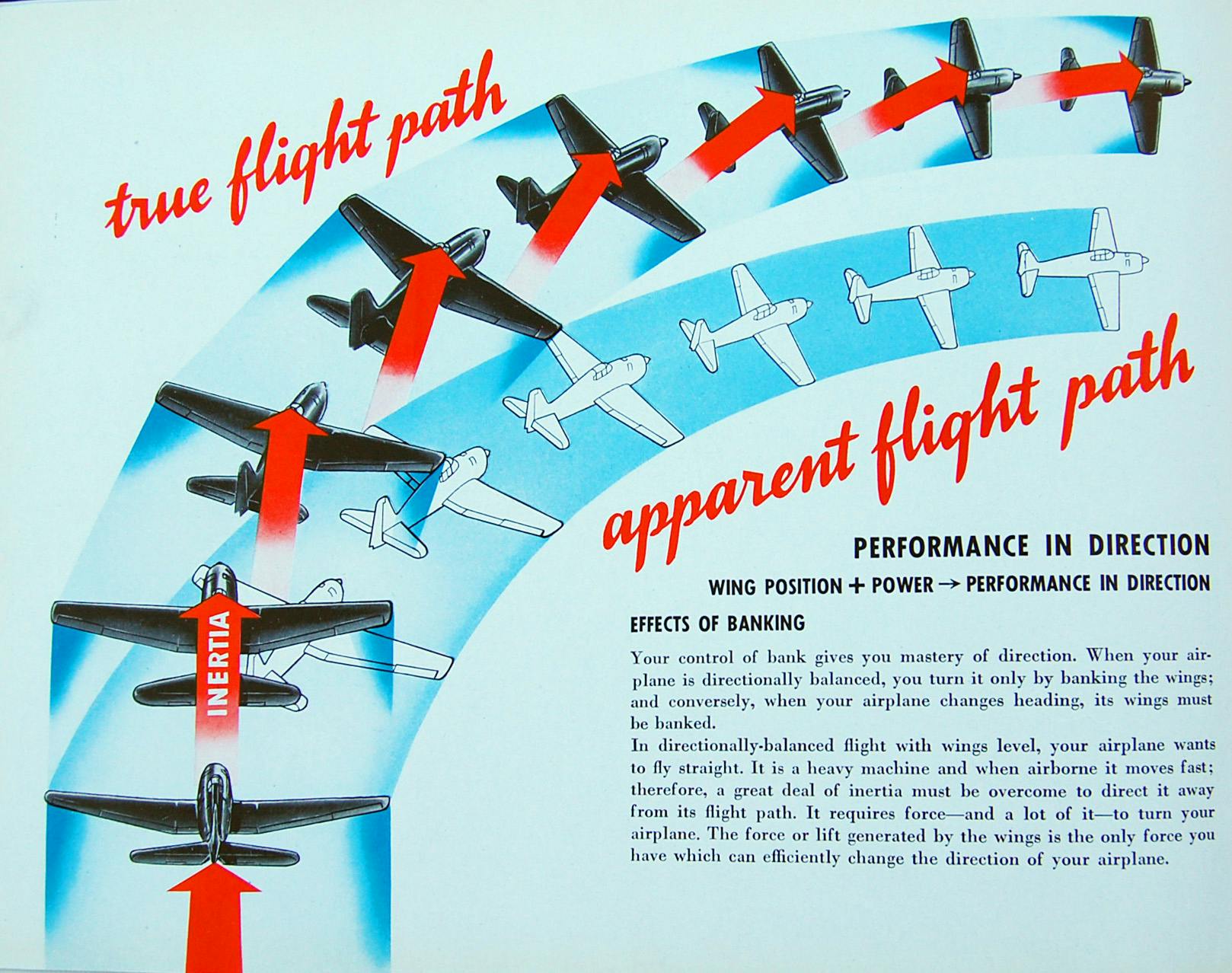

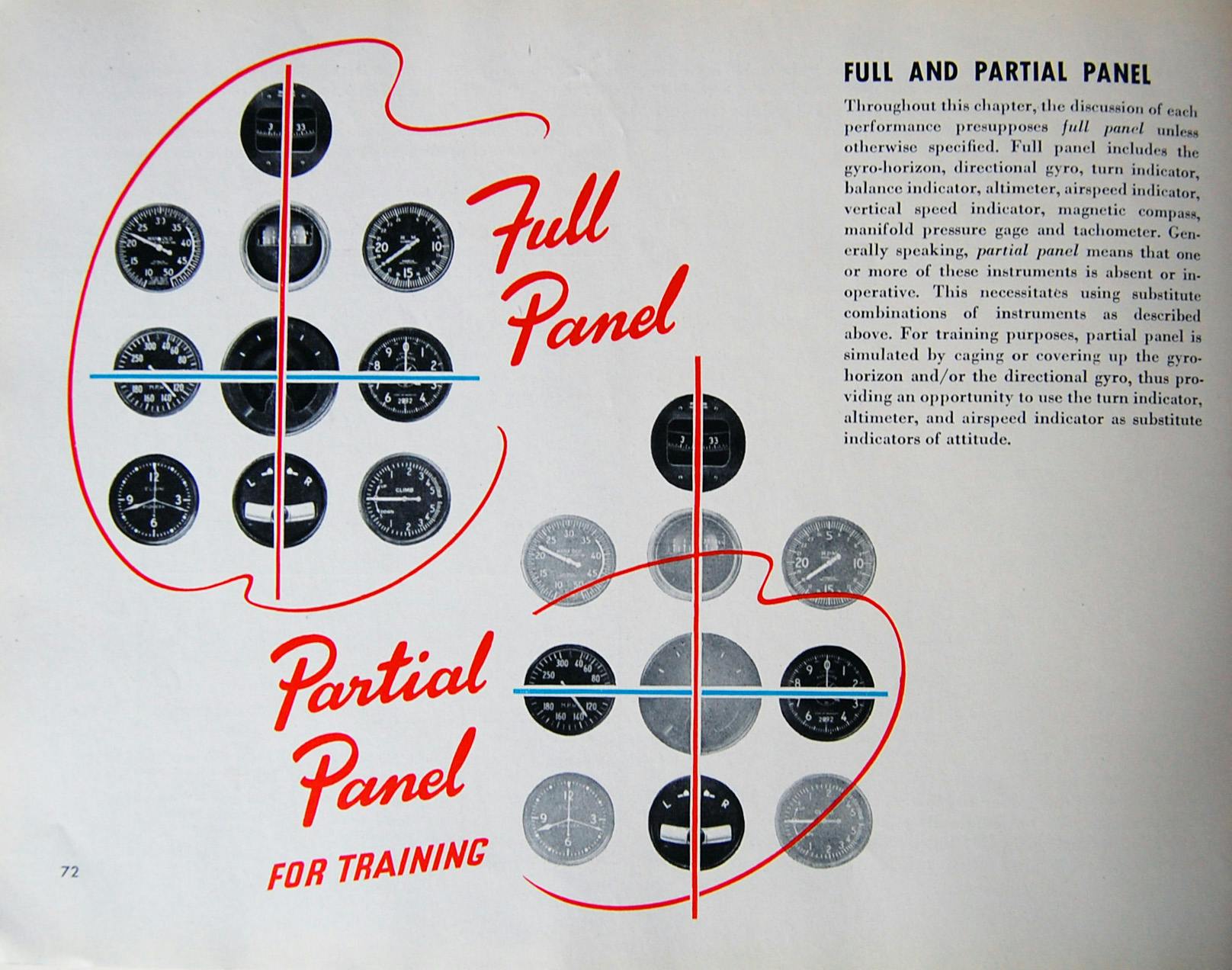

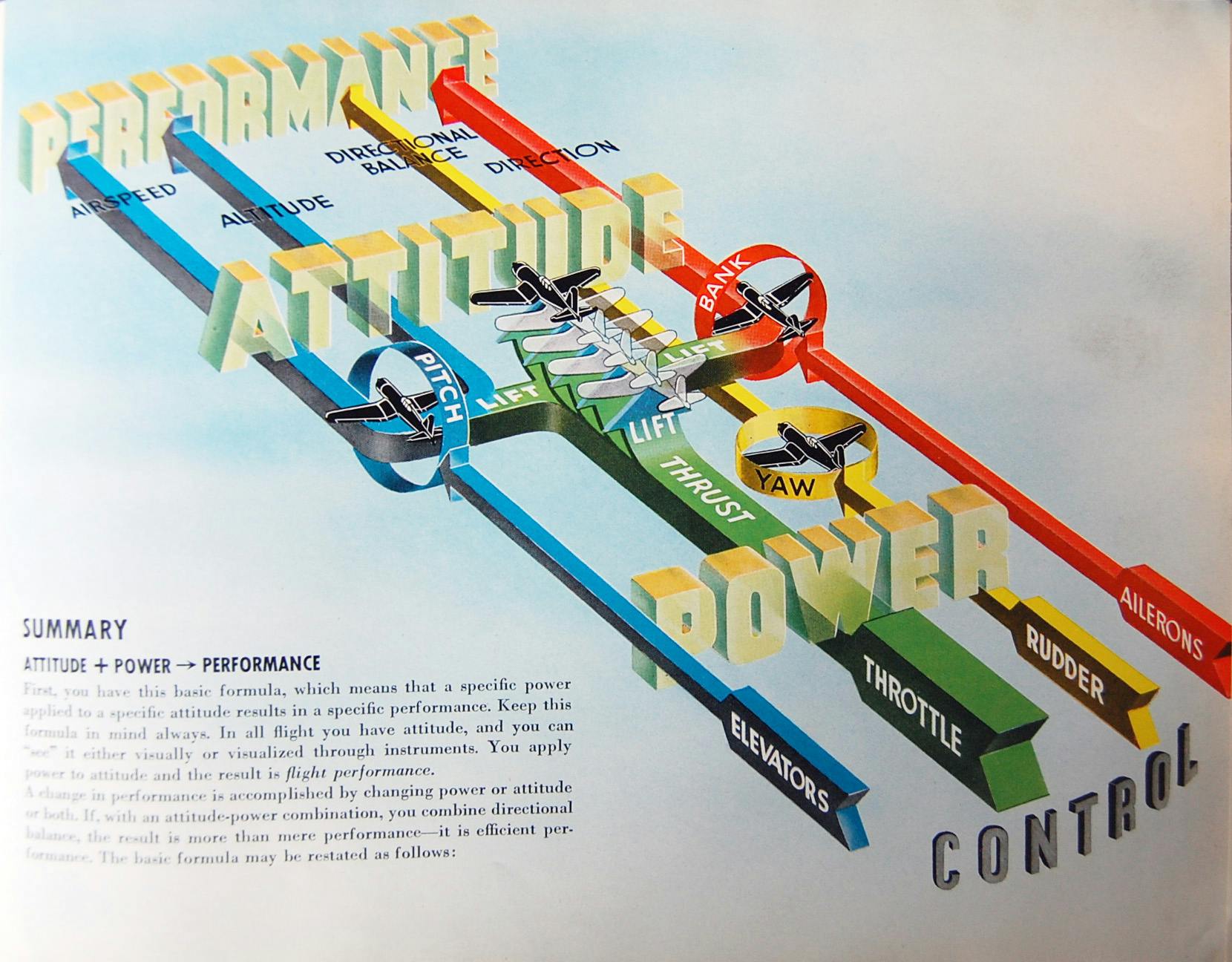

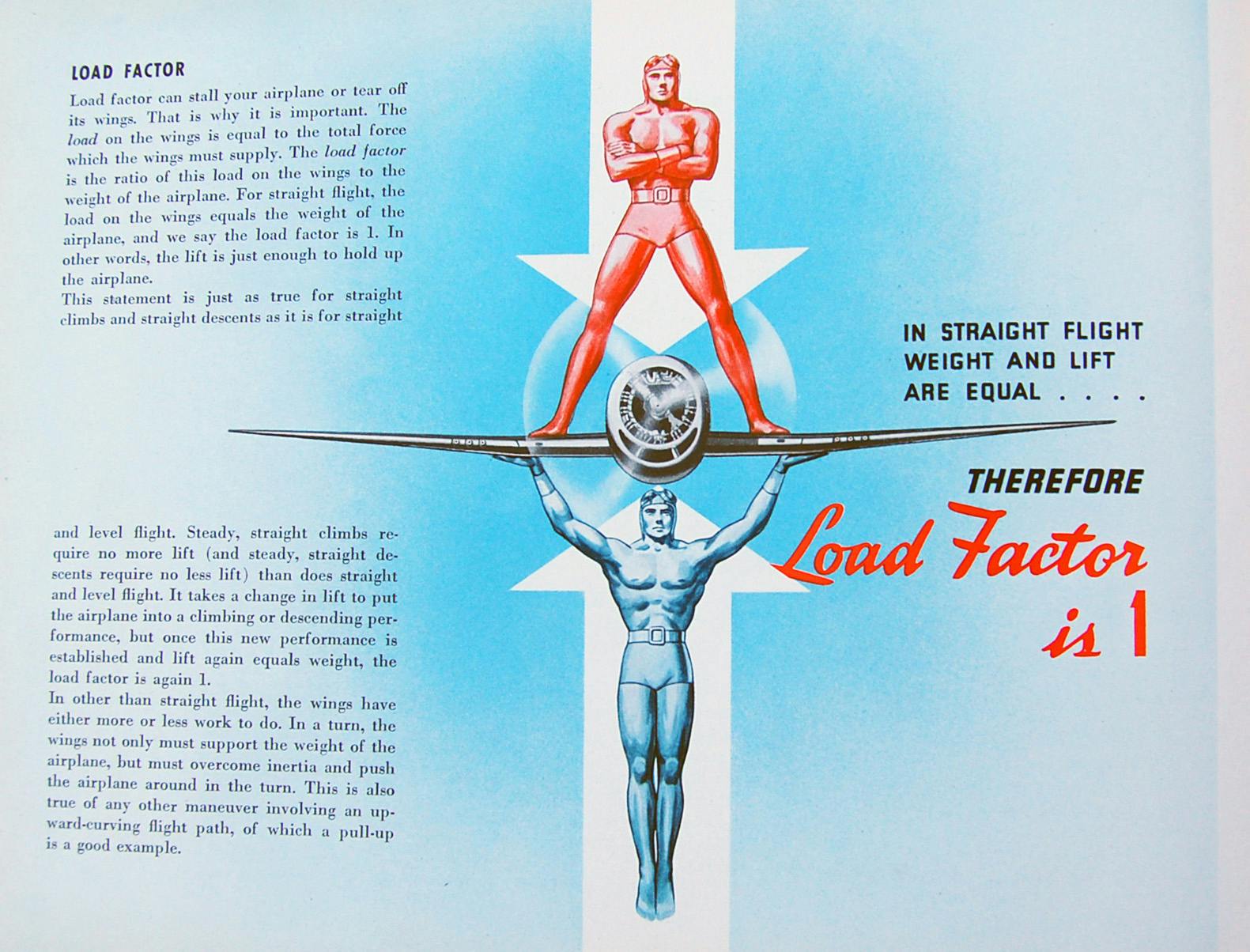

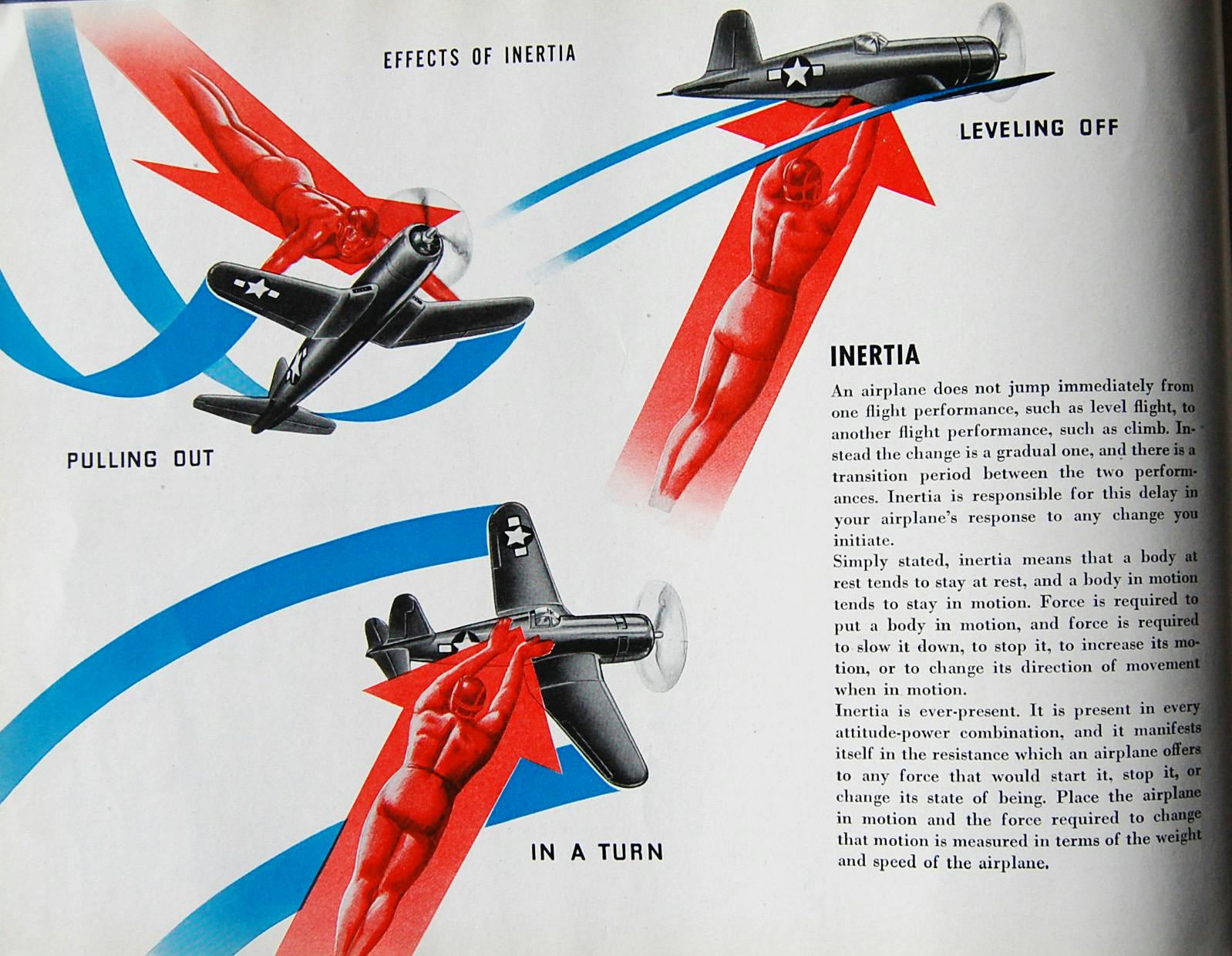

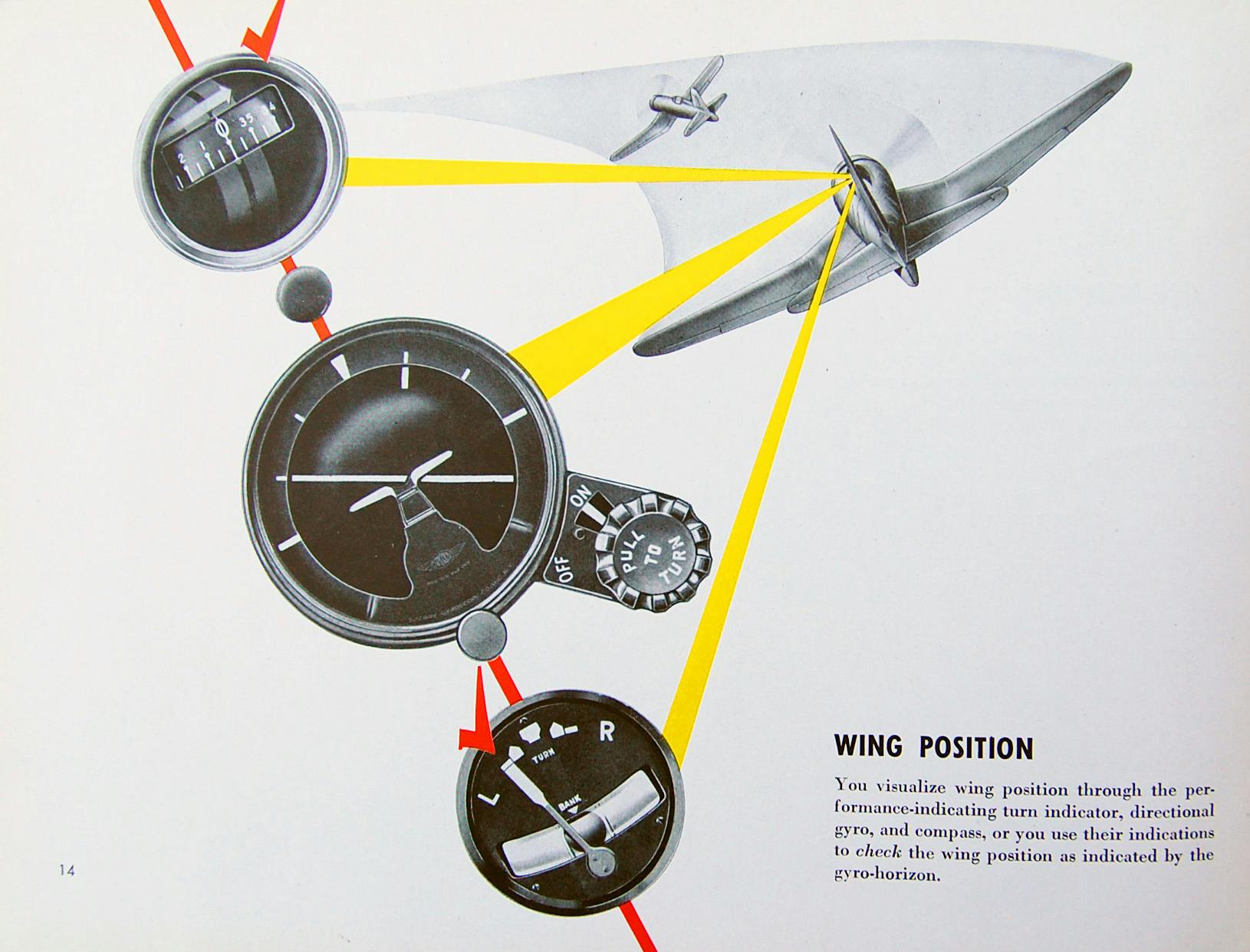

Technology rapidly changed during WWII, and new pilots also had to be trained to use it. One of the most challenging—and essential—techniques that green pilots needed to know was how to fly by instruments alone at night or in other low-visibility conditions.

To quote the U.S. Navy: “With the array of accurate and reliable instruments that are now standard equipment in all modern planes, flight is effective, precise, and successful under all conditions. These servants of flight attitude and performance are yours to command and to use if you will, but you must understand what they tell you and learn how to use them.”

In 1944, Earl’s Graphic Engineering department was contracted by the Navy to illustrate Flight Thru Instruments, a training manual for pilots. Earl’s department comprised the auto industry’s first dedicated design team, first established in 1927 as the Art and Colour Section and renamed the Styling Section in 1937 before switching to Graphic Engineering for the duration of the war. Earl was neither an engineer nor talented at rendering graphics. He did, however, have a good eye for proportions and lines and was skilled in communicating his vision to his designers.

When Earl’s department received the Navy’s commission in 1944, the only computers were the size of a large room and useful mostly for calculating trajectories for big naval guns. The drawings, of course, were all done by hand … and what drawings they were!

The planes are all rendered beautifully, with the associated graphics done in a visually arresting, late Art-Deco style. Nearly every page is worthy of a framed display.

The book was published by the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations on January 1, 1945. Lest you think that was late in the war, that date was right in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge in Europe and, in the Pacific, the bloody fight for Iwo Jima, which was still almost two months into the future. Pilots who trained with Flight Thru Instruments likely saw combat.

Though the book is now 75 years old, I asked a pilot whom I know, who is rated to fly multi-engine aircraft, to take a look at it. He said that while modern planes have “glass cockpits,” that is, fully digital instrument panels, the basic flight instruments still have the same functions. Most of Flight Thru Instruments is still relevant to pilots, and copies still circulate among flying enthusiasts.

The influence of automotive designers upon the war effort didn’t flow one way only. A well-known bit of automotive lore has GM design chief Harley Earl taking his staff of stylists to Selfridge Field (today Selfridge Air National Guard Base) north of Detroit in 1941 to get an early look at the then-secret Lockheed P-38. The dual rudders of the sleek, twin-fuselage plane proved inspirational. Designer Frank Hershey was particularly taken with the look of the plane, as William Knoedelseder records in his book FINS; to Hershey, the P-38 evoked the bodies of sharks and sailfish: “beautiful, sleek, shiny, and streamlined. The embodiment of power, speed, maneuverability, and stability.”

WWII would have a lasting effect on automotive styling, as Earl would later explain: “When I saw the P-38 rudders sticking up, it gave me an idea for use after the war.”

Earl’s idea would come into play for the 1948 Cadillac, the first all-new postwar design for GM’s flagship luxury brand. The flowing line sweeping from the front fenders to the rear gave the car a muscular look. (In the original drawings, the rear fenders tapered down to echo the curve of the trunk lid, following pre-war fashions.) Earl assigned Hershey the task of visually raising the rear end to grant the car a more modern look and stance. The younger stylist left the basic lines intact but turned up the end of the sweeping rear fenders sweep to incorporate the taillamps, thereby inventing what we know as tailfins.

The connection between Lockheed’s P-38 and the rakish tailfins of the ’50s, however, is only one expression of automotive stylists’ creativity in WWII. Earl repurposed the menacing lines of a fighter aircraft to add flair to civilian transportation, but in the 40s, WWII was far more than a design inspiration for Earl and his team. The automotive stylists who illustrated Flight Thru Instruments were trying to save pilots’ lives and make their own contributions to winning a war. Their work resonates as today’s automotive engineers and workers tirelessly labor to assists health care workers and their patients in the war COVID-19.