Media | Articles

Garrett AiResearch’s Compressed Air–Powered Dragsters Started with Promise and Ended in Disaster

In the early 1960s, Garrett AiResearch, then best known as the maker of turboprop aviation engines, was moving into the automotive market. With a Garrett T05 turbocharger under the hood of the first production car with a turbocharger—the 1962 Oldsmobile Jetfire—it might have made sense for Garrett AiResearch to promote turbos at the drag strip. However, as a brand-promoting publicity campaign, the company instead drew from its existing aviation technology and hired some hot rodders to use turbines to slingshot their dragsters toward the 200mph mark.

Curiously, though, they weren’t jet turbines, although they were indeed turbines used in jets. Rather than a nitromethane-fueled V-8 equipped with AiResearch turbos, Garrett’s exceedingly fast dragsters were powered by turbines running on air, albeit in highly compressed form. Even more surprising was the fact that the two air-powered dragsters were among the fastest cars of the era. The project started with optimism and success but ended in a disaster.

The story begins in Tucson, Arizona in the 1950s. Gary “Red” Greth, Lyle Fisher, and Don Maynard were childhood friends who started drag racing in high school. After they graduated, they formed the Speed Sport racing team, running a roadster with a 331-cubic inch Chrysler Hemi V-8 fed by six carburetors. In 1957 they set a drag racing record of 169.11 miles per hour. A series of Speed Sport Roadsters followed, and the team gained enough credibility and prominence that they were able to turn professional, and took to competing in races and exhibition runs at drag strips across the country.

Their success both on the track and in promoting the Speed Sport team may have been why, in May of 1961, they were approached by three engineers working for the AiResearch division of Garrett with a novel idea to power a dragster. AiResearch was located in Phoenix and Don Hedinger, Cal Senson, and John Brown, approached the Speed Sport team at an Arizona drag strip with the proverbial offer they couldn’t refuse.

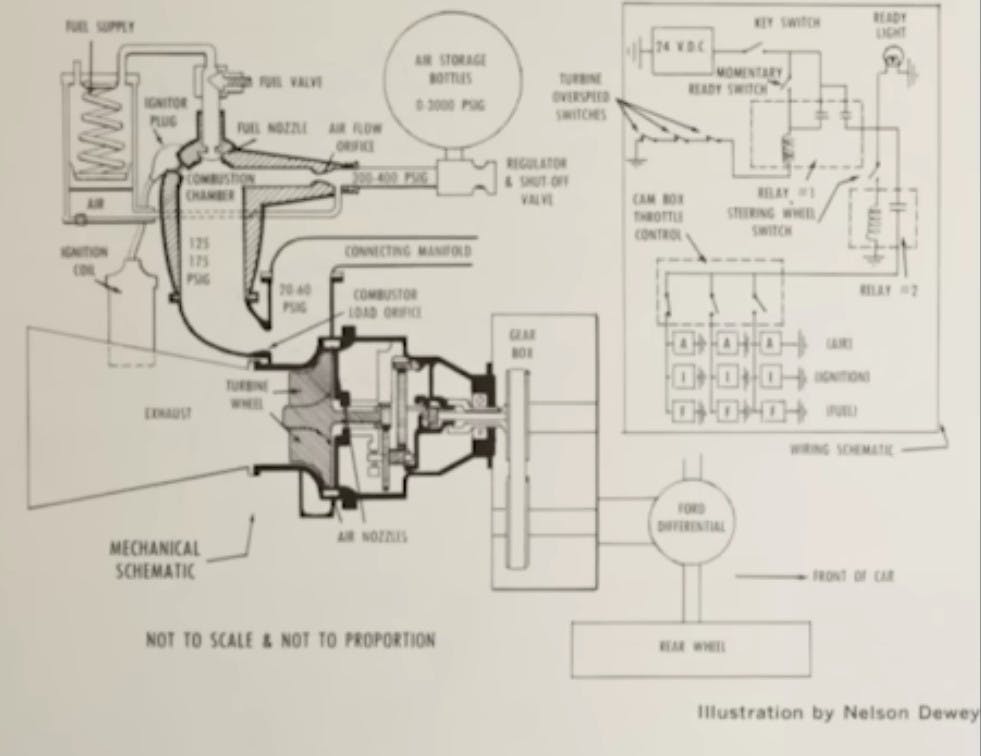

One of Garrett’s products was a line of pneumatically powered turbines used as starter motors for jet engines. A commercial jet airplane can have three different turbine engines—there are the main engines that provide the thrust needed for propulsion, and there is an Auxiliary Power Unit used to provide electrical power to the plane. The APU also provides compressed air to power a third turbine, the main engine’s pneumatic starter motor. That’s the type that got incorporated into the dragster.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

With sufficient air supply, a single starter turbine could produce 750 lb-ft of torque, far more than anything the Speed Sport team was getting out of their Hemis. Even better, the turbine only weighed 35 lbs. The AiResearch engineers proposed using multiple turbines to produce levels of horsepower and torque hitherto unheard of in motorsports.

What made the offer impossible to refuse was the fact that in addition to AiResearch doing all the drivetrain engineering, the project was financially underwritten by the turbine maker, and they were also going to handle the publicity campaign.

While the drivetrain was Garrett’s responsibility, the Speed Sport team was responsible for the chassis. It had a conventional tapered ladder frame with a ’37 Willys front end and a 115-inch wheelbase. The turbines were mounted behind the driver, who sat in approximately the middle of the car. The frame rails were a bit overbuilt for the job as the Speed Sport IV did its early runs without a body.

Garrett commissioned Indy 500-winning car builder Eddie Kuzma to hand form an aerodynamic body that evokes images of Land Speed Record jet cars. Famed customizer Dean Jeffries did the paint. While the three large exhaust ports might give the impression that the compressed air also provided some direct propulsion, in use the thrust proved to be minimal.

Initially, there was some friction between the AiResearch engineers and the Speed Sport team because what works in theory may not be practical when the rubber meets the road, or drag strip in this case. Eventually, the two teams worked out their differences.

Still, there were obstacles to overcome. Compared to nitromethane, air may not weigh very much, but the pressure vessels needed to store enough compressed air for a quarter-mile run can have some mass. The first iteration of the air-powered dragster used two oblong tanks that weighed 450 lbs each, almost half the total weight of the car, which tipped the scales at over 2,200 lbs. While that doesn’t sound like much for a road car, as a drag racer, that’s a super heavyweight.

Three starter turbines were ganged together in a triangular layout with splined output shafts, a chain drive and a single center sprocket that fed a reduction gear set whose output shaft was connected to a Ford truck rear axle. The reduction gears were necessary because the turbines could spin at speeds of up to 70,000 rpm.

There were teething issues. To begin with, between the torque of the turbines and the weight of the air tanks, even with 1962 vintage rubber, not nearly as sticky as modern compounds are, they were breaking axles. Also, they ran into a couple of problems caused by temperature, one more aesthetic and one more practical.

When it wasn’t breaking axles, the car got off the line quickly, trailing clouds of snow that formed as the compressed air expanded and cooled, freezing moisture in the air. However, the car would also peter out after only 200 feet as the tanks expended their air.

That was because the air hitting the turbine was very cold. If you remember basic physics, hot things expand and cold things contract, and the dense, cold air did not have sufficient volume to do a full 1/4 mile run.

To solve the problem with broken rear ends, the AiResearch team used a sophisticated electronics package, with metering circuits and cutoff switches. When the driver hit the throttle, a pressure regulator would open, feeding air to two of the three turbines. A second later, the third turbine would spin up.

To deal with the weight, AiResearch bought four lightweight spherical pressure tanks from Lockheed, which had been using them for an electrically powered aircraft project. They weighed just 200 pounds total, a 700 lb weight savings.

To address the air volume issue, they added a combuster with a constant fuel supply and a spark plug firing 25 times a second, in between the pressure regulator and the turbine. Just about any flammable liquid would work. The combuster would instantly heat the freezing cold air to 1300°F, causing it to expand greatly.

I suppose that one could say that the AiResearch guys turned it into a proper turbine engine, but the purpose of the combuster was just to expand the air, not provide power to the turbine blades.

The revisions turned the Speed Sport IV into a competitive drag racer, capable of smoking the tires for the full 1/4 mile run, and low 9-second elapsed times.

After fine-tuning things, on June 17, 1962, Greth ran an 8.75 with a trap speed of 161 mph.

AiResearch booked the team into exhibition runs across the United States, including at the NHRA nationals in Indianapolis. In July, at Cordova, Illinois, the Speed Sport IV reached 189 mph, and that was with some glitches that caused the turbines to shut down 200 feet short of the traps.

The teams spent the late summer and early fall trying in vain to hit the 200mph mark like the top fuel cars of the era. By October, though Greth and Fisher shared in an interview with Drag News that they’d need a new car that would be lighter and less complicated to hit that mark.

AiResearch would indeed build a second, lighter, car but for some reason, the Speed Sport team was not involved. It is speculated that Greth wasn’t thrilled with how the car sounded. Instead of the roar of a combustion V-8, the turbines ran mostly silently. Perhaps the Speed Sport team wanted to get back to competitive racing instead of doing exhibition runs.

Whatever the reason, the second air-powered car would be piloted by Dale Grantham, another Arizona drag racer. By 1962, Grantham was a touring pro, racing as a featured act as far away as the East Coast. Likely from all of them being at the same tracks at the same time, Grantham had gotten to know Hedinger, Senson, and Brown, and it was decided that he would be at the wheel of the second air-powered dragster.

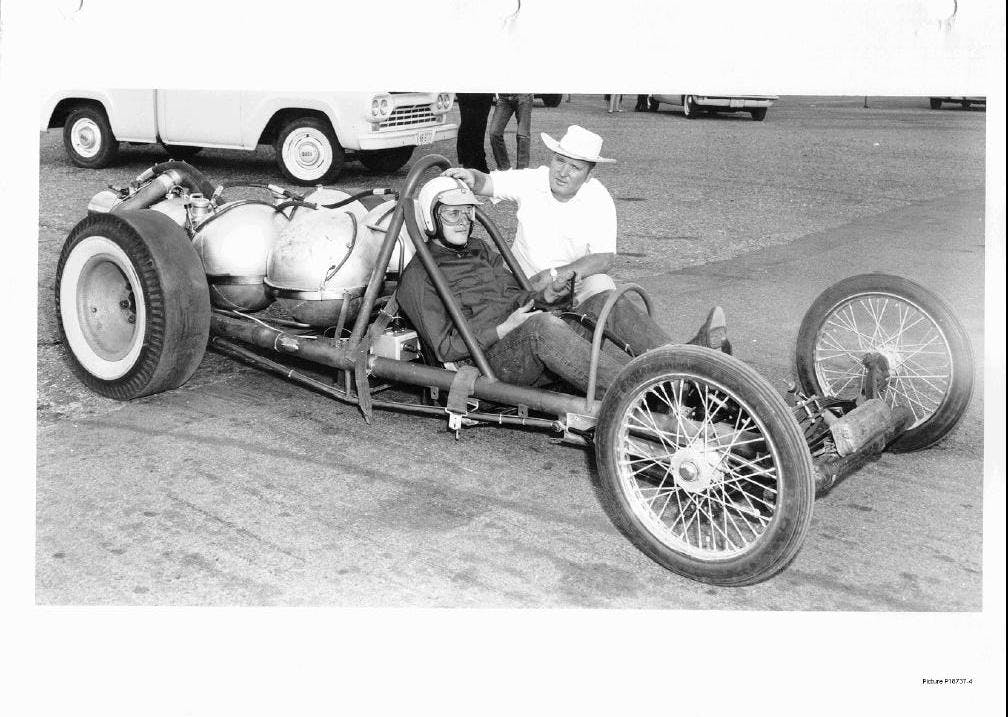

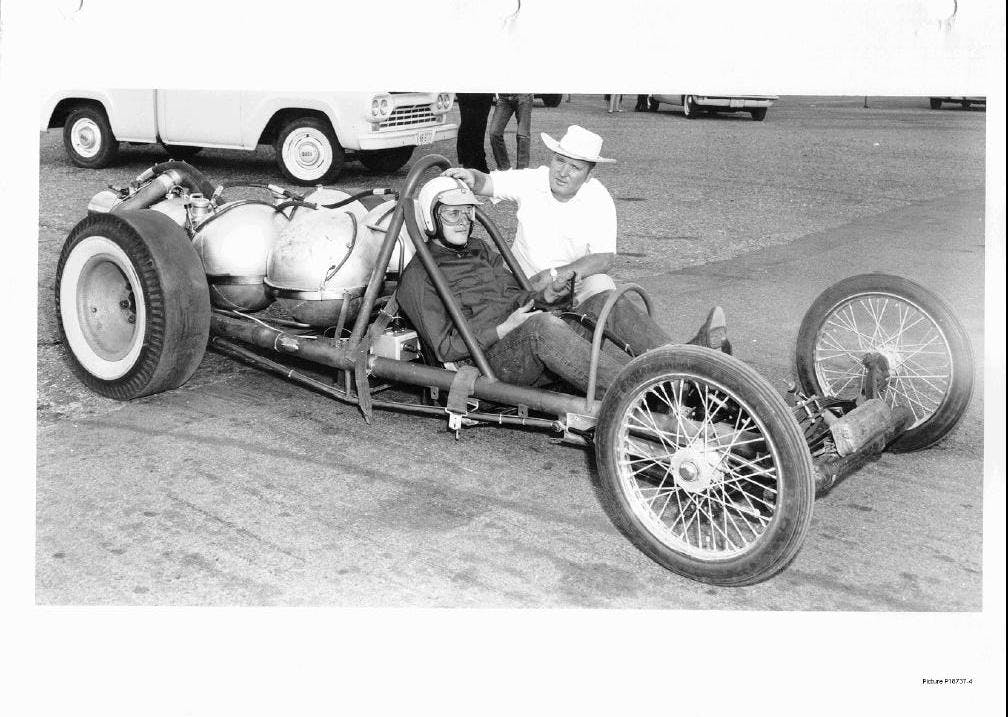

The second car was a scaled-down version of the era’s slingshot top fuel cars and weighed in at just 600 lbs without the driver. The top of the roll bar was just 33 inches from the ground, just taller than the racing slicks. The spherical air tanks were replaced with tanks similar to those used in welding, mounted at the sides of the frame ahead of the driver. The chain drive was replaced with a much lighter-weight system of planetary gears. Grantham drove the car in reclining position, not unlike that of today’s open-wheel formula racers.

Out of the box, the second air car was a half-second faster than its predecessor, running in the low 8-second range. The team hoped that by the end of 1963, the car would break into the 7-second bracket and hit 200 mph. Turbine speeds were reaching 85,000 rpm. The air dragster was getting major publicity and was seen as possibly the future of the sport.

Then, disaster struck on July 21, 1962, at Fontana Raceway in California. Grantham’s dragster was about halfway through its quarter-mile run when one of the turbines failed and exploded, sending shrapnel into the stands, injuring a young girl seriously enough that she had to be treated at a hospital. While her injuries were not life-threatening, the air dragster was immediately banned at Fontana and many other tracks in California. Track operators across the country stopped booking exhibition runs.

Apparently, someone at Garrett decided that they didn’t need the bad publicity and pulled funding from the project. Dale Grantham was injured in a racing wreck in another car, and while recovering his shop was broken into and looted. There’s no record of him racing after 1963.

The Speed Sport team returned to competitive racing in 1964 with a conventional nitromethane-powered dragster with a V-8 combustion engine.

In 1963 Garrett AiResearch merged with the Signal Corporation, taking its name, and that company later merged with the Allied Corp, forming Allied-Signal, which later rebranded under the Honeywell name. Honeywell spun off the turbocharger business into a company called Garrett Motion in 2018, and the brand makes turbochargers to this day.

There is no indication of the fate of the two air-powered dragsters.

Garrett APU’s and other turbine products are still made (under the Honeywell brand) at that same facility in Phoenix. Apparently, the 12″ concrete floors that the milling machines are bolted to, are hard to replicate. Next to the airport, it will eventually be the site of the next runway, when that happens. So many cool ideas were hatched there, I saw a turbine powered semi-tractor (18 wheel variety) prototype, in the early 80’s. Not great on fuel efficiency, but it sounded awesome driving on city streets.

Absolutely fascinating, I never knew of the existence of this car or any air powered car. I love reading articles of this nature on Hagerty, thank you.

Experimentation and risk-taking used to be hallmarks of the drag racing community. Not-so much these days, but those pioneers from the late ’40s through the ’70s made the sport exciting and interesting. I’m glad I lived through those glorious times as a low-level participant and big-time fan of the quarter mile!

This was a very interesting concept . Just think of the many “ rear Engine “ fabricated cars that used that early chassis fabrication.

The Power plant , and running gear and Hardware could be replaced with more Sophisticated,Materials today .

Pioneers , wonder where are the Cars !

This is a perfect example of what was going on that time. Technology was moving so fast that the supporting technologies couldn’t keep up with them. You could build an even more powerful jet engine but having the control surfaces on an aircraft ( while even in the hands of the very best pilots) to keep them stable was beyond their limits. A lot of lives lost pushing those boundaries. The Cold War era produced a paranoid belief that no matter what ‘you’ did, ‘you ‘ were falling behind that fed on itself. I always think of the movie ‘ Fail Safe’ ( a serious as a heart attack version of ‘Doctor Strangelove’ released that same year that I highly recommend ) when a general comments – paraphrasing – ” We’re moving too fast. Our machines are getting too far ahead of us .” That is in many ways what happened here.

“Technology was moving so fast that the supporting technologies couldn’t keep up with them. ”

If the “technologies” stayed where they were originally designed to be used, there would not have been a problem. Reading the descriptions of the aircraft components used to power a drag racer made it clear to me this was truly an accident waiting to happen. Obviously, human nature is to always push the limits and try new things, and it is easy to look back, but this was quite a risk.

Awesome article, like some of the others commenting I was not aware of these state of the art air dragsters back in the day. Thanks for a great read.

The most surprising thing to me was that Lockheed had an electric airplane project over 60 years ago?

Please revisit paragraph 11. It says 450 lbs is nearly half of 2200 lbs. Not sure where the typo is, but there is one

The first iteration of the air-powered dragster used two oblong tanks that weighed 450 lbs each, almost half the total weight of the car, which tipped the scales at over 2,200 lbs

Two at 450 lbs. each !

There were two of them

It looks like a Saturn rocket on the back end. It’s a very cool idea. I do wonder if this was tried today if they would be more successful. Still 8’s and 9′ in the 1/4 mile isn’t too bad.

AiResearch was a much different company in the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s than it is today. As the full name implied, AiResearch “Manufacturing” Company of Arizona—the courage demonstrated in those days was legendary.