Media | Articles

How Frank Zamboni’s frankensteined Model A revolutionized ice rinks

You may have heard that Italian design firm Pininfarina—famous for the Ferrari Testarossa, among other automobiles—has turned its proverbial pen to rework the Zamboni ice resurfacer. What better time to reshare the story of the original Zamboni and the man who invented it? —Ed.

You might be surprised that the Zamboni Ice Resurfacer, the motor vehicle most associated with ice hockey, was not invented in some frigid northern clime like Minnesota or Canada. In fact, it was created in a place not usually associated with ice at all—southern California. Frank Zamboni (1901–1988) first moved to southern California in 1920 with his brother Lawrence to work in their older brother George’s car repair shop, but the two younger Zambonis soon struck out on their own and opened an electrical repair service to install and repair refrigeration units for local dairies.

The pair eventually expanded their business to include block ice, which shippers of California produce used to keep goods fresh when shipped across the country; however, as the railroad and trucking industries embraced refrigeration, demand for block ice dropped and the Zamboni brothers started exploring other ways they could exploit their expertise in refrigeration and ice-making.

By the late 1930s, touring shows by Olympic figure-skating champion Sonja Henie and the Ice Capades greatly increased the popularity of ice skating, though there were few recreational rinks in southern California. Seeing an opportunity, Frank, Larry, and one of their cousins built the Iceland Skating Rink in Paramount in 1939. With 20,000 square feet of ice surface, Iceland was, and still is, one of the largest skating rinks in the United States. And with room for up to 800 people to skate comfortably, Iceland was an immediate success.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

However, in a classic case of “what were they thinking?” the Zambonis initially built Iceland as an open-air rink, not considering how southern California’s intense sun and hot, dry Santa Ana winds could affect the ice surface. A dome was quickly added to the structure to shade the rink.

Next, Frank Zamboni devoted himself to solving a problem facing rink operators and hockey teams across North America: how to resurface the ice to repair the wear and tear from skaters degrading the surface and producing cracks and ruts.

At the time, rink operators resurfaced their ice by shaving the surface with a scraper pulled by a tractor. A handful of workers would use shovels to gather up the shavings and then clean the surface by spraying it with water and then using rubber squeegees to get rid of the dirty water. Clean water would then be applied to create a smooth new surface as it froze. The whole process could take up to an hour.

Frank thought that a dedicated resurfacing machine might do the job better and faster. His first prototype in 1942, a machine built into a trailer-towed sled, was not successful. Five years later, he re-approached the problem with a more holistic solution: a single machine that would shave the ice, remove and store the shavings for disposal later, wash and squeegee the ice, and put down fresh water for a new surface.

Frank built that prototype in the back of the Iceland rink, located just a few blocks from the current Zamboni factory. Using war surplus material, the engine and transmission from a Jeep, and the front-wheel-drive front axle from a military truck, Frank fabricated a front-drive, front-steering ice resurfacer with water tanks up front and a tank for the snow shavings in the back. That prototype showed promise but was abandoned because of problems with a chattering scraper blade, a too-small snow tank, and traction issues—even when using tire chains, which were counterproductive to a final, smoothly-finished ice surface.

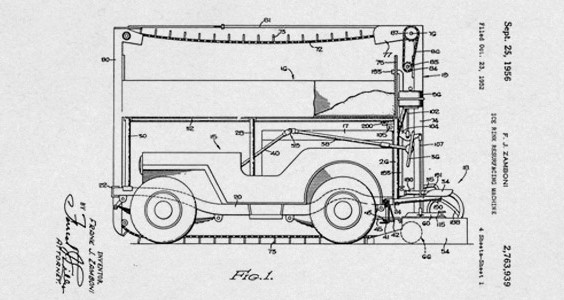

To overcome traction issues, the next prototype had both four-wheel drive and four-wheel steering, since Zamboni used the same surplus front-wheel-drive axle at both ends. Happy with the results, he applied for a patent in 1949, and in 1953, U.S. patent No. 2,642,679 was granted to Frank J. Zamboni.

The first truly practical Zamboni machine, the 1949 Model A, used a hand-built chassis and surplus components, as mentioned, in addition to a hydraulic cylinder repurposed from a Douglas bomber. It added a cover for the shavings conveyor so shavings wouldn’t fall back onto the ice surface, a large wooden tank for the snow, and an in-tank snow-melting system. The sides of the snow tank were hinged so the shavings could be removed with shovels.

The Model A introduced a feature used by every Zamboni machine since, a wash-water system that first cleaned the ice surface and then recycled that water before laying down a thin layer of clean water to create a perfectly smooth surface.

Frank found that while four-wheel drive was definitely an improvement, four-wheel steering was not. When driving near the side dasher boards of the rink, trying to steer away from the boards made the rear wheels steering directly into them, so the Model A had conventional two-wheel steering via the front wheels. Zamboni’s Model A was used exclusively as a prototype and resurfaced the ice at the family-owned Iceland rink in Paramount where it still resides, having been restored in the late 1990s.

In 1950, Sonja Henie’s ice show was using Iceland as a practice facility during a West Coast tour. After seeing how quickly the Model A put down a mirror-smooth surface, she asked Frank Zamboni if he could build one for her in time for an upcoming show in Chicago. By then, Frank had redesigned his machine to be mounted on a conventional Willys Jeep. The Willys’ four-wheel drive and front steering matched the layout the resurfacer needed and came ready-made as a functioning vehicle with a drivetrain. Frank worked day and night to make the resurfacer’s parts and then piled them into a U-Haul trailer, which he towed to Chicago with the machine’s own Jeep before assembling everything in the Windy City.

Zamboni would end up building four Model Bs, one for the Winter Garden rink in Pasadena, one for the Ice Capades, and two for Ms. Henie, who had one shipped to Europe for her across-the-pond shows.

With orders pouring in, Frank incorporated Frank J. Zamboni & Co. It wasn’t because he was bragging. He originally planned to call it the Paramount Engineering Co., after the city where his original Iceland rink was located, but that name was already taken by another firm.

The Model C and Model D machines, from 1952 and 1953 respectively, had noticeable changes though they were still built over a complete Jeep. The rear-seated driver’s position was raised and the snow tank lowered to improve the driver’s view and increase the tank’s capacity.

It was with the Model E that Zamboni standardized his resurfacers. Prior to the E, each successive unit had slight changes. In 1954 and 1955, the Zamboni company built and sold 20 Model Es.

One of them was purchased by the Boston Bruins of the National Hockey League, which came about thanks to the Ice Capades. The touring skating group had an evening show scheduled in the Boston Garden arena for New Year’s Day in 1954. Bob Skrak worked for the ice show and was responsible for operating the Model B Zamboni that traveled with the show. The Bruins had a day game, and after the teams practiced, Skrak took the Zamboni out to resurface the ice for the game. Bruins management was so impressed that it ordered a machine and even took out some of the Garden’s seats to facilitate getting the Zamboni on ice. In 1988, when the Bruins took delivery of a new Zamboni machine, they had their Model E restored by the manufacturer; it is now in the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto.

As ice skating’s popularity increased, so did Zamboni sales. Rink operators wanted machines that could carry more water and hold more shavings, so to gain more space, Frank switched from mounting everything on an already-assembled Jeep to using the chassis without a body for the Model F. Sales were high enough that Zamboni started dealing directly with the Willys factory in Toledo to source the chassis and other components.

In 1964, the Zamboni HD was introduced, which is the machine many people associate with the brand, since many are still in service. Zamboni eliminated the conveyor for shavings, replacing it with a vertical auger system in the back of the vehicle, and sped up the process of dumping ice shavings with a hydraulic lift on the snow tank. The HD was the first production Zamboni resurfacer to use a dedicated Zamboni chassis, rather than the frame from a stripped-down Jeep.

The year 1978 saw the introduction of the 500 Series Zamboni machines, the world’s most popular ice resurfacer. It was originally available with a choice of air-cooled or liquid-cooled engines but is now also available with battery power. Remember, ice resurfacers generally operate inside of closed buildings. Back in the 1950s, exhaust emissions from a Zamboni machine’s Jeep Hurricane engine were probably not noticeable, thanks to all of cigarettes and cigars then smoked at hockey games, but indoor air quality is a serious issue today. Many community rinks host youth hockey, and nobody wants kids needlessly exposed to exhaust emissions.

The Zamboni Model 550 was the world’s first production battery-electric ice resurfacer, and today the Zamboni company offers the model 560AC, which is not only battery-powered and emission-free but has also has automated many of the tasks that used to be operated by the driver. (As yet, however, Zamboni hasn’t offered a touch-screen-based infotainment system, or a driver-selectable Sport mode.)

By the way, it’s not really called a Zamboni. Just as not every hook and loop fastener is Velcro, not every ice resurfacer is a Zamboni. That basic patent expired a long time ago and the company does have competitors, so it prefers the trademarked name, the Zamboni Ice Resurfacer.

For some strange reason our youngest daughter was enamored with the Zamboni (well, likely not really the machine, but with the name, which was infinitely fun to say, I think). In the mid-’90s, I arranged to have her “win” a ride on one at our local hockey rink. We have video and pictures, and I must say, her sparkling grin rivaled the glisten of the ice. She even got to get in the seat and drive it for a bit, which we’d never seen any other winners get to do. After she returned to her seat, we found out why: the driver was hitting on her and offered to let her drive as an enticement to go on a date with him! (she was in her 20s)

She would have enjoyed reading this history. If I had known this story before her passing, I would have definitely taken a family trip to take her to the Paramount Rink and the Zamboni factory. Thanks for informing us and for dredging up a great family memory, Ronnie!

In addition to being something of a car nut, I was also a dedicated recreational hockey player until knee problems forced me to stop playing last year. A series of concussions didn’t help but I prefer to blame the knee as a “career” cut short by knee problems (albeit at the tender age of 68) is about the only thing my game will ever have in common with Bobby Orr.

Anyway, big thanks to Frank Zamboni for his invention. And the article is right, the fumes from the old machines would stink up the rink – newer propane or electric powered resurfacers are much preferred.

As my youngest son finished his hockey career last season after 7 years, I have always been amazed by the Zamboni as it does its job. Thank you for this enlightening story of its beginnings.

@DUB6, I hadn’t seen your post when I put in m somewhat trivial response below.

Sorry to hear of the loss of your daughter but I’m pleased to hear that she got to drive the Zamboni. I hope the story brought up a good memory.

Most of us old hockey players have an unfulfilled wish to drive the Zamboni but never get to. The closest I ever got to it was moving the nets out of the way at the end of the game and then racing the machine to the exit so I could get off the rink without skating through the fresh layer of water it laid down.

WRLotus, your response was neither trivial nor anything to apologize for – and I enjoyed all of your comments. Thank you for your nice words. She would be tickled to hear that she had driven a machine that maybe a bunch of hockey players yearned to do and not gotten the chance! 😄

[PS] – I never got her to tell me whether or not that guy got a date. I hope he wasn’t risking his job trying to get to go out with her!

I was a young specialist in Germany in the 80’s when our motorpool received a weird addition – a vehicle you see hauling bags at the airport (still not sure why we got that?!). It had a dodge slant 6 in it, and was heavy, but I swear it was like a Zamboni, and I would drive it around our motorpool imagining I was resurfacing the ice at Joe Louis Arena. ; )

My parents first dated at the Paramount rink in the late 1940s. They saw some of the early versions working after their racing and figure skating sessions, getting ready for hockey.