Media | Articles

Ford’s Flathead V-8 Gave Power to the People

In the early 1900s, horsepower was almost exclusively for the Gatsbys of the world. Ford’s flathead V-8, introduced in the depths of the depths of the Great Depression, changed all that. But it needed some help from car obsessives, who went on to invent what we now know as hot-rodding. Preston Lerner tells their story. —Ed.

This story first appeared in the September/October 2024 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Join the club to receive our award-winning magazine and enjoy insider access to automotive events, discounts, roadside assistance, and more.

They call Ed Iskenderian the Camfather. Now 103, the founder of Isky Racing Cams has been grinding camshafts for nearly eight decades. He has worked his magic on just about every engine you can imagine—big ones and small ones, race winners and boat anchors, motors that became legends and others destined for junkyards. But if you want to put a smile on his wide, grizzled face, ask him about the engine that put him on the map: the flathead Ford.

“I started off with the Model T, of course,” he says. “That was simple and easy to understand. They made 15 million Model Ts, they say, and almost everybody could afford one. But then the flathead V-8 came out in 1932, and, by golly, Ford did a beautiful job with that engine. It looked like a racing engine, and it was so well built! Man, they made that engine for almost 20 years. All I can says is, ‘Wow!’”

We all know the basic story: The flathead came, the flathead saw, the flathead conquered. It introduced millions of car buyers to what eventually became a kind of American birthright: V-8 power. Immediately after World War II, it then powered the popularization of the hot rod. In fact, it’s hard to imagine how hot-rodding would have developed if the flathead—affordable, widely available, and wonderfully receptive to high-performance modification—hadn’t existed. “The flathead ruled,” says automotive historian Ken Gross, who owns two hot rods motivated by venerable Ford V-8s. “I mean, it was the motor for hot-rodding.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Yet as much as the flathead spawned hot-rodding, hot-rodding undoubtedly helped shape the flathead and, more broadly, the all-American obsession with horsepower that still rules today. Contrary to the creation myth, the Ford V-8 didn’t spring to life as an instant icon. It was born prematurely, and it suffered from all sorts of debilitating childhood diseases. Over the years, Ford implemented plenty of cures—so many that you almost need a shop manual to tell one model year from another. But the flathead was transformed into a masterpiece only after it was massaged by a coterie of brilliant self-taught machinists, fabricators, and engineers such as Isky, Ed Winfield, Vic Edelbrock, and Stu Hilborn.

These giants—and dozens more like them, some household names, others remembered now only by the cognoscenti—designed and built cylinder heads, intake manifolds, carburetors, camshafts, fuel-injection systems, and so on that doubled, tripled, and finally quadrupled the horsepower of the simple, relatively crude V-8. They also established the ethos that underpins hot-rodding to this day. As Alex Xydias, the founder of the famed So-Cal Speed Shop who recently passed away at 102 years old, put it: “Once a hot rodder got ahold of something, he was determined to improve its performance. That’s how the flathead became the king of hot-rodding—and helped create hot-rodding, really.”

It seems only right and fitting that Henry Ford should be the conceptual father of the flathead. The success of the company had been the product of his seminal insight into what consumers wanted at the turn of the 20th century. But the America of the Roaring Twenties was a more affluent and technologically savvy place than it had been when the Model T was introduced in 1908. So, in 1928, the Tin Lizzie was replaced by the Model A. Sales were brisk—until Chevrolet introduced a smoother, more powerful straight-six the following year. Model A sales cratered, and in 1931, Ford shuttered the mighty River Rouge plant, putting 60,000 employees out of work.

To compete with Chevrolet, Ford’s son, Edsel, spearheaded the development of a six-cylinder engine. But Henry had a bug up his you-know-what about sixes. “I have no use for an engine with more cylinders than a cow has teats,” he once declared. To prove his point, he terminated Edsel’s project by having one of the prototype motors hoisted on a crane, then dumped on the pavement below. It was a perfect metaphor for the up-and-down relationship between father and son.

Still, with the country mired in the Depression and Chevy eating Ford’s lunch, Henry realized that he couldn’t let the anatomy of a cow determine the fate of his company. What Ford Motor Company needed, he decided, was an eight-cylinder engine, and he believed that a V-8 was the way to go. This configuration was more compact than the straight-eights found mostly in race cars and top-of-the-line luxury cars, and two extra cylinders meant more power than the Chevy inline-sixes, plus a whole lot of bragging rights.

V-8s had been around since the turn of the century and were, in fact, already a staple of the Lincoln model lineup. But the V-8s of the day were built up from separate crankcases and cylinder barrels, then put together by hand. So they were expensive to produce and time-consuming to assemble—an obvious nonstarter for a car that was being developed to appeal to the masses.

Ford wanted an engine that was cheap, simple, robust, and reliable. His solution? Casting the block as a single unit. At the time, this was a daunting metallurgical challenge, and Ford engineers endured countless failures during months of secret experimentation. They finally got a prototype to live on a dyno in early 1932. When engines began rolling off the assembly line later that year, they became the world’s first mass-produced monoblock V-8s.

Contrary to the creation myth, the Ford V-8 didn’t spring to life as an instant icon.

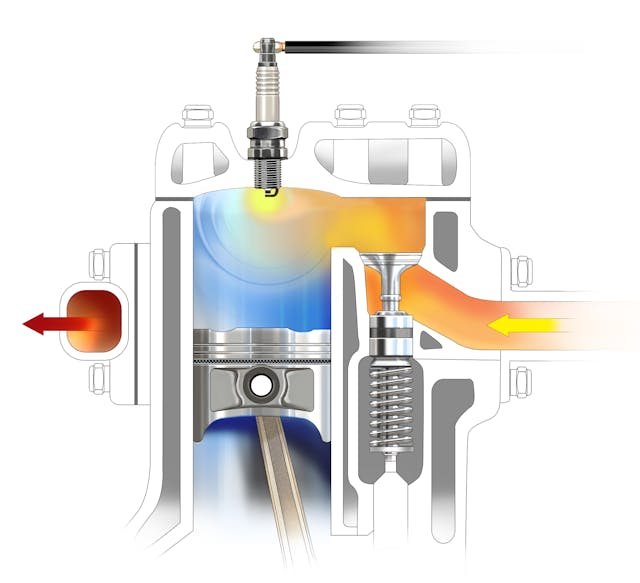

The top of the engine was no less ingenious. Ever since the Ernest Henry–designed Peugeots won the French Grand Prix in 1912 and the Indy 500 in 1913, everybody understood that dual-overhead camshafts with hemispheric combustion chambers was ideal, as it allowed for more fuel and air to enter the cylinders and for higher-rpm operation. But this was also the most costly option, which is why a DOHC motor didn’t carry the blue-oval logo until the all-conquering four-cam Indy Ford debuted in 1964.

Performance-wise, the best alternative to a twin-cam motor, where the cams directly actuate the valves, is one in which a camshaft located in the center of the engine block actuates overhead valves via pushrods. It’s no coincidence that a few hundred million pushrod OHV motors have come out of Detroit over the past three-quarters of a century. But Ford was looking for something even cheaper and more basic. So he commissioned a so-called L-head engine, whose signature feature is intake and exhaust valves situated in the block, next to the cylinders. If you want to get technical, this is a side-valve design. But because the cylinder heads are flat, the motor is known generically as a flathead.

The Ford V-8 debuted in March 1932 in the all-new Ford Model 18, producing 65 horsepower. To put that number in context, the Model A, which had been discontinued in 1931, made only 40 horsepower. The Model B, which still had a four-cylinder and cost $10 less than the Model 18, made 50 horsepower. It was, in short, a major leap—and, by the way, edged out Chevy’s six (which made 60 horsepower that year).

Ford promoted its wonder engine with a slick, intertwined “V8” logo and a killer slogan: “The greatest thrill in motoring.” Unsurprisingly, the Model 18 outsold the Model B by more than 2-to-1. It would have been more like 10-to-1 if Ford had been able to build V-8s fast enough to meet demand. Ford offered flatheads for sale as stand-alone units as well. Engines were so cheap and plentiful that the owners of Model As started swapping out the old four-bangers for junkyard V-8s. The converted cars were dubbed AV8s.

In 1934, Ford reclaimed the U.S. sales crown that Chevrolet had held for the previous three years. That April, Henry Ford received a grammatically challenged handwritten note signed by Clyde Champion Barrow, of “Bonnie-and” crime-spree fame. “While I still have got breath in my lungs I will tell you what a dandy car you make,” he wrote. “I have drove Fords exclusively when I could get away with one. For sustained speed and freedom from trouble the Ford has got ever other car skinned and even if my business hasen’t been strickly legal it don’t hurt anything to tell you what a fine car you got in the V8.”

Alas, killjoy historians believe the note is a forgery. Ditto for another letter extolling the virtues of the flathead supposedly written by Public Enemy No. 1 John Dillinger, which lends credence to Henry Ford’s oft-quoted dictum that “history is more or less bunk.” So, too, is the modern notion that his V-8 sparked an immediate revolution in the automobile industry. The truth of the matter is that all wasn’t rainbows and unicorns in flathead country.

The engine had been rushed into production to save Ford’s bacon in 1932. Early models suffered from core shifts that caused blocks to crack. Customers complained about chronic overheating, cracked pistons, bearing failures, and excessive oil consumption. Then as now, racing was seen as a good way to show off an engine’s potential. So, in 1935, Edsel Ford agreed to a proposal floated by master promoter Preston Tucker (covered in great detail in “Tucker: The Man, The Machine, The Dream”) to build a fleet of race cars to compete in the Indianapolis 500.

Harry Miller, the colossus of early American racing, was hired to design the car. He created a lovely, low-slung, thoughtfully streamlined body to house a mildly uprated version of the flathead Ford. Ten chassis were built. Five cars went to the Speedway. Four qualified. None finished. Although the engines didn’t fail, the humbling experience soured Ford on racing, and the company largely stayed out of motorsports until Henry Ford II, Henry’s grandson, greenlit a return to Indy in 1963.

The fiasco at the 500 spotlighted the larger failure of the flathead to win converts in the burgeoning universe of automobiles modified by enthusiasts to speed them up. Hot rods, as such, didn’t yet exist; the term wasn’t coined until after World War II. But ambitiously modded cars known as “hot iron” or “gow jobs”—for “get up and go,” Isky theorizes, though nobody knows for sure—were popular in Southern California, and car clubs staged meets at Muroc and the other dry lakes in the Mojave Desert, north of Los Angeles, to see how fast their stripped-down, hopped-up roadsters could go.

Although it seems like these proto-hot rodders should have been all over the V-8, they avoided it for a couple of reasons. First, a full complement of effective speed-demon parts already existed for the four-cylinder Fords, and better the devil you know, et cetera. The larger issue was the systemic weaknesses of the flathead, whose fundamental design had been compromised to cut costs.

The architecture of the engine, with the valves adjacent to the cylinders, meant that it didn’t breathe well, and a lone single-barrel carburetor didn’t help. Additionally, the V-8 was something of a teakettle because the water jackets ran through the block, and the middle two exhaust ports were siamesed, or combined. Subsequently the header (the part of the exhaust that bolts directly to the engine) had six pipes rather than the eight you’d expect—a major choke point. Worse, the blocks were susceptible to cracking because the deck surface was thin, and the placement of some of the studs securing the cylinder heads was suboptimal.

Ford recognized these problems and took corrective action over the years. By 1938, the flathead featured 24, rather than 21 cylinder-head studs, a two-barrel Stromberg 97 carb, and a pair of water pumps relocated to the front of the block for better cooling. Ford also replaced the poured Babbitt crankshaft bearings with modern inserts, which were easier to manufacture and service. By bumping up the compression ratio to 6.12:1, the flathead now made 85 horsepower at 3800 rpm.

By the late 1930s, the go-fast guys were finally showing the engine some love. The most important of these figures was the reclusive Ed Winfield, who was venerated like an ancient oracle. After going to work for Harry Miller when he was 14, he formed his own company to build the carburetors that won 11 consecutive Indy 500s. “Winfield was regarded as a true genius,” Gross says. “He was the first guy to really figure out the magic of camshafts.”

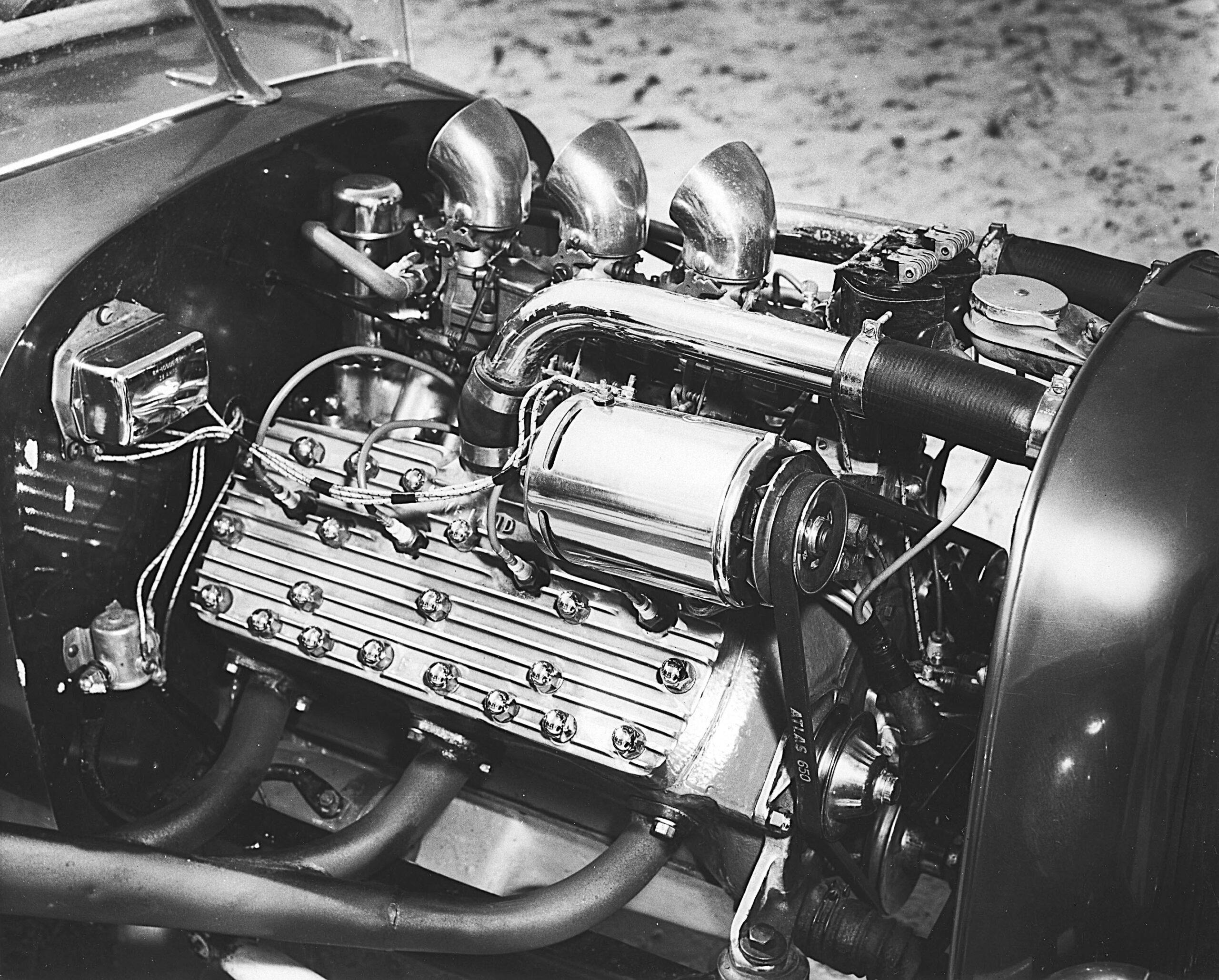

Cam design was—and still is—something of a black art. But designing and fabricating intake manifolds was a more straightforward exercise. Over the years, hundreds if not thousands of manifolds were built to adapt the flathead for two-, three-, and quad-carb setups. Prewar manifold pioneers included Hollywood’s Eddie Meyer, the nephew of three-time Indy winner Louis Meyer, and native Angeleno Phil Weiand, who used a wheelchair after a crash in his flathead-powered ’27 T roadster.

By 1940, dry lakes records were being set by a formidable Kansas transplant named Vic Edelbrock, who’d outfitted his ’32 roadster with a Winfield cam and a high-rise dual-intake manifold sold by another leading Los Angeles manufacturer, Tommy Thickstun. Edelbrock later redesigned the intake runners to improve airflow and built a manifold that resembled a slingshot. In years to come, his “slingshot” manifold was so successful that it helped launch what we now think of as the speed-equipment industry.

But just as aftermarket development of the flathead was taking off, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. World War II was a mixed blessing for guys like Edelbrock and Iskenderian. For the next three years, most of them served in the military or went to work for shops and factories that supplied the war effort. But this exile from the world of high-performance cars primed Southern California for an explosion after the war.

“There was a massive boom,” says hot-rod historian Tony Thacker, who owns a ’32 Ford chassis with a ’27 roadster body and a 1940 flathead. He’s also the co-author with Mike Herman of Ford Flathead Engines: How to Rebuild & Modify. “You’ve got all of those returning service people with a little bit of money. They’re looking for the excitement that’s gone out of their lives, and there are masses and masses of cars around. Here in Los Angeles, they had foundries, machinists, pattern-makers—everything needed to make stuff reasonably cheaply and really, really quickly. And they had the dry lakes, which gave them a place to race.”

In 1946, Ford raised its game by boring out the flathead to 239 cubic inches and bumping up the compression to 6.75:1. The stock engine was now rated at 100 horsepower. But this was merely the blank canvas. Speed shops and DIYers machined ports and cylinder heads to improve airflow. Stock intake manifolds and carburetors were replaced, sometimes by fuel injection. “Hotter” cams, whose lobes are typically ground so as to push valves open farther (“lift”) and/or keep them open longer (“duration”) were fitted. (This had the added benefit of making the flathead sound even gnarlier.) Cylinders were bored out and stroker cranks were installed to increase displacement.

Aftermarket cylinder heads could be found everywhere. More enterprising suppliers did away with the “flat” part of the flathead altogether. Dixon and Alexander converted the L head to an F head by moving the exhaust valve outside the block. Meanwhile, Riley and Tornado offered cylinder heads that transformed the flathead into an overhead-valve engine. But the most exotic OHV conversion was the Ardun head named for its creators, the Arkus-Duntov brothers, Zora and Yura.

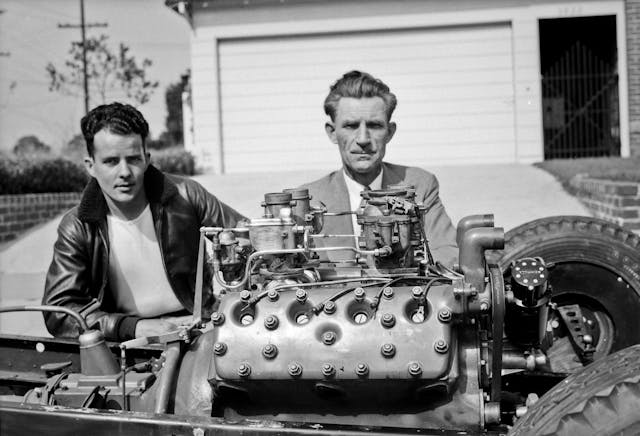

Prewar players such as Winfield, Weiand, and Edelbrock picked up where they’d left off after the war, and they were soon joined by big names from the track racing world, like Fred Offenhauser and Clay Smith. But as hot-rodding grew, it attracted fresh blood. Ed Iskenderian was one of the newbies who jumped into the flathead-tuning game.

“I decided I’d like to try making my own cams,” he recalls. “Winfield had told me how to build a cam-grinding attachment. So I went to an auction and bought a cylindrical grinder for $700. I looked in a book that told you how to design a cam, and I practiced and practiced until I had a cam that looked good. Then a kid I was helping with his Ford V-8 bought it from me for $20, not realizing that I had no reputation.” He chuckles. “When he got it running, I could hear the tappet noise a half-a-block away.” He chuckles again. “I was ashamed of the noise, but it ran good on account of that.”

Ed Pink was another newcomer. Later, he’d become famous for building Hemis for drag racing, Porsches for endurance racing, and Cosworths for Indy. Like Isky, he started messing around with flatheads—in his case, under the hood of his ’36 Ford—while he was a teenager. And like Isky, he was mentored by a wise, old head—longtime Edelbrock employee Bobby Meeks, who’d helped establish the best practices for optimizing the Ford V-8. In years to come, Pink would modify flatheads so radically that just about the only original piece was the block.

“The block was a weakness; it would crack cylinder walls,” he says. “The three main bearings were another weakness. It wasn’t made to be a race engine. Stock, they were rated at 85 horsepower. On methanol alcohol, if you had a really good one, you got it up to 200 horsepower. Most of the time, they got around 160, 170 horsepower. I had one with a 3-71 supercharger, and with straight alcohol, it made about 380 horsepower. But when we went to 30 percent nitro, we put the rods on the ground.”

Just as important as the mechanical advances was the growth of a broader audience. By the end of the 1940s, the feared postwar recession had largely failed to materialize, and a rising generation of young enthusiasts was hungry for automotive fun. The country’s first major hot-rod show was held at the National Guard Armory in Los Angeles in January 1948. At it, Robert “Pete” Petersen distributed copies of the first issue of his hot-off-the-presses publication, Hot Rod magazine. The cover featured a flamed, flathead-powered Model T roadster that went 136.05 mph on the dry lake at El Mirage. The next year, the first organized drag race was held between a pair of Ford V-8s in Goleta, near Santa Barbara. The favorite was Tom Cobbs, who was driving a ’34 roadster with a then-rare supercharger. But he was beaten by Edelbrock shop manager Fran Hernandez in a ’32 coupe with three carbs—and a jolt of nitromethane, a closely guarded trade secret.

The market for high-performance parts, especially flatheads, was big, and dozens of builders filled the void: Barney Navarro, Frank Baron, Harvey Crane, Chuck Potvin, Earl Evans, Al Sharp, Jack Engle, the Spalding brothers, the list goes on and on. A network of speed shops sprang up to sell everything from manifolds and cylinder heads to T-shirts and fuzzy dice. The biggest player was Ansen Automotive Engineering, co-founded by midget racer Lou Senter. (Coincidentally, Ansen and Iskenderian shared booth space at the Armory hot-rod show in 1948.) But the outpost that proved to have the most staying power was the So-Cal Speed Shop, originally situated in Burbank and still in business to this day.

In 1949, owner Alex Xydias, who’d been a B-17 flight engineer in World War II, teamed up with Road & Track editor-to-be Dean Batchelor, who’d been a B-17 gunner and radio operator, to build a car for the first hot-rod meet at the Bonneville Salt Flats. They re-bodied a dry-lake belly-tank chassis with a streamlined shell of their own design and installed an Edelbrock-built Mercury flathead that was more or less par for the course.

“We were doing what everybody else was doing,” Xydias admitted. “I know it isn’t very exciting when you ask somebody what he did, and he says, ‘Not very much.’ But by the time we got to it, thousands of kids and mechanics had been dickering around with the flathead for years, boring the crap out of it, porting and relieving and grinding a little bit here, a little bit there, using all those sacred speed secrets that they’d learned in somebody’s garage at night.”

That streamliner carried Batchelor to a one-way pass at a mind-boggling speed of 193.54 mph. The next year, the car set a record at 208.927. To put this in perspective, the flathead gow jobs that ran on the dry lakes had topped out at about 130 mph before the war. “It showed that if you have a streamlined body and a flathead, you’re going to go fast,” Xydias said.

The performance of the So-Cal ’liner proved to be the high point for the flathead. Yes, Ford significantly improved it in 1949, and by 1953, it was making 110 horsepower—125 in Mercury form, with a longer stroke. But by then, the engine had become a victim of its own success. It had demonstrated the viability and market appeal of affordable V-8 power, and the competition had rushed to join. Cadillac and Oldsmobile introduced overhead-valve V-8s in 1949, and the Chrysler Hemi, which arrived in 1951, was in another league altogether. The final nail in the flathead’s coffin was the debut of the small-block Chevy in 1955, which was GM’s rain dance on Henry Ford’s grave.

Automakers had also, by this point, taken note of hot-rodding culture, brazenly promoting horsepower in advertising. Many of those who had honed their craft on the flathead found their way into factory-backed programs: Zora Arkus-Duntov, for instance, joined General Motors in 1953 and circulated a memo arguing that Chevrolet could use hot-rodding as a way to sell cars to younger buyers. He soon found himself in charge of hopping up the company’s floundering sports car, the Corvette.

Hot-rodding itself continued to mature over the next half-century as the rough edges were sanded off the hobby. The Boyd Coddington–style street rod, with glossy paint and machined billet accents, became the standard-bearer of the era, and seemingly infinite variations on the 350-cubic-inch Chevy emerged as the preferred powerplant. And everybody was happy—until they weren’t. Critics started grumbling that hot-rodding had become too homogenized and predictable. Aficionados agitated for a return to the hobby’s roots, with more individuality and ingenuity. And how better to embrace the spirit of hot-rodding than to re-place a ho-hum small-block Chevy with the flathead V-8 that Henry Ford had developed as his gift to the American workingman?

Thanks to this sort of thinking, the flat-head is enjoying an improbable renaissance. Ground zero is H&H Flatheads in La Crescenta, north of Los Angeles, where the storage yard looks like a junkyard filled with flathead flotsam—blocks, heads, cranks, cams, distributors, oil pans, studs, bolts, and everything else needed to build motors that would have been at home on the dry lakes in the 1930s or Van Nuys Boulevard in the 1950s. “I try to get out three [turnkey] engines a week, and I’ve got 50 on back order,” owner Mike Herman says.

And these engines have to be built, not just assembled. He can’t go to the Ford Performance Parts catalog and buy a fully dressed crate flathead or a short block easily accessorized with goodies from aftermarket suppliers. A ton of labor goes into each build, and even then, he’ll never come close to matching a small-block Chevy on a dyno. Which is fine with Herman.

“You don’t need 350, 400 horsepower to go from light to light or drive to a car show,” he says.

“Flatheads’ll run with dirt in them, they’ll run on six cylinders, they’ll run with s***y spark, they’ll run with s***y gas. They sound so good and look so iconic, and they’ve been in so many movies and magazines over the years that people still love them. The flathead helped build our country. It’s Americana.”

Ford’s flathead V-8 isn’t the best engine ever built. But in some corners of the hot-rod world, it’s still the best-loved.

***

What Makes the Flathead Special?

The simplest stuff often takes the most work. That was certainly the case for the flathead. Ford’s quest to create an affordable, mass-production V-8 required a $50 million investment (more than $1 billion in today’s dollars).

Ford design engineer Charles Sorensen’s strategy was to integrate as many components as possible into a single elaborate casting to save cost, weight, and machining. FoMoCo’s final design combined eight cylinders, the upper half of the crankcase, oil galleries, coolant passages, the flywheel housing, and all intake and exhaust runners into a single iron casting.

Two Ford Model A four-cylinder water pumps were employed to save cost. The “flat” heads were drilled and tapped for spark plugs, and they provided combustion-chamber clearance for the opening valves. While the intake runners were nicely direct, exhaust passages had to wrap either around the ends of the block or between the two center cylinders. To resolve overheating issues, water pumps were moved from the heads to the block after a few years of production. Carburetion advanced from a single- to a two-barrel Stromberg riding atop a two-plane intake manifold in 1934.

The result was a genuinely mass-production V-8, with a single Dearborn, Michigan, foundry supplying 3000 engines per day to 33 Ford assembly plants. Machining required less than three hours. A bare block became a fully assembled V-8 in two hours.

The engine at launch delivered five more horses than Chevy’s overhead-valve six and was notably lighter and more compact. Pricing initially ranged between $460 and $650 (about $10,000 to $14,000 today). No wonder it was a hit. Nearly 100,000 customers placed orders for the ’32 Ford V-8 sight unseen. By the time production ended, more than 15 million had been built. —Don Sherman

In 1937 Chevrolet got 4 main bearings (splasher) 85 HP and hot Rod potential.