Media | Articles

Ford vs. Everyone (including Chevrolet) at the dawn of American car making

Breaking into the car business, Henry Ford failed twice. To make his third attempt stick, he became the fastest man on earth and beat rivals at racing.

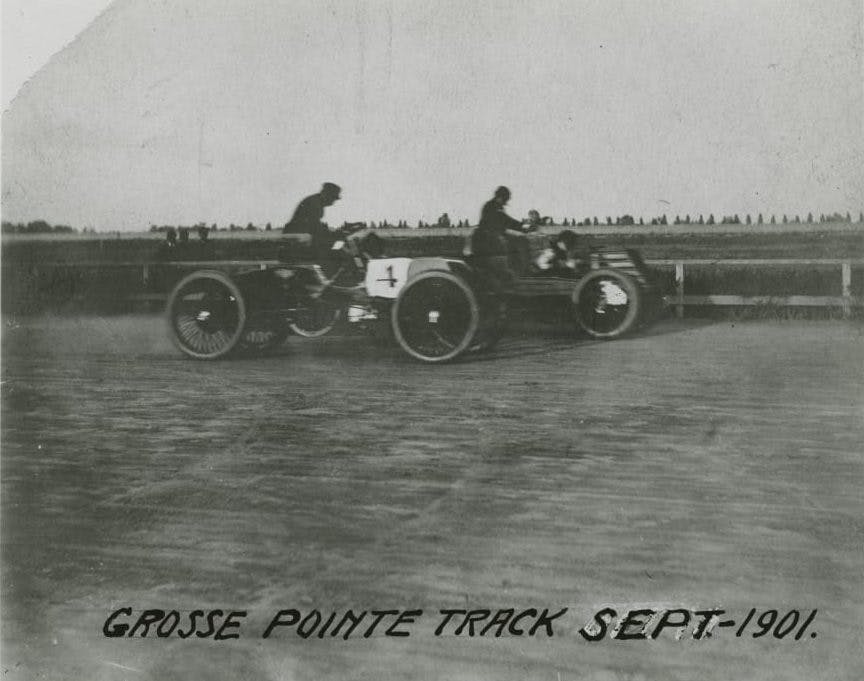

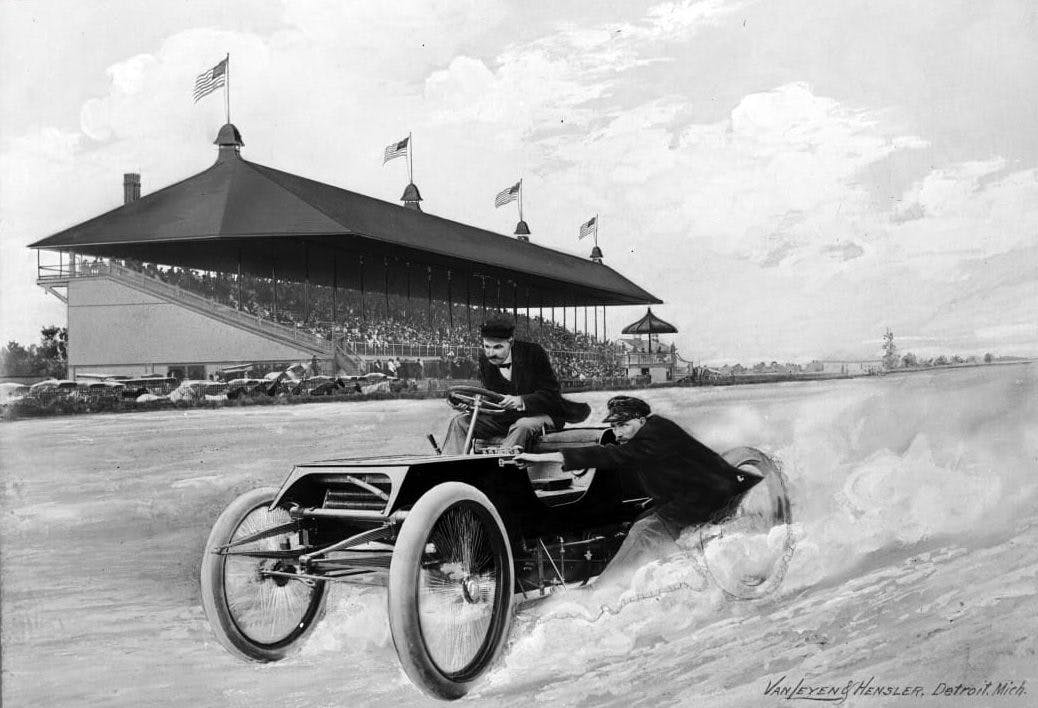

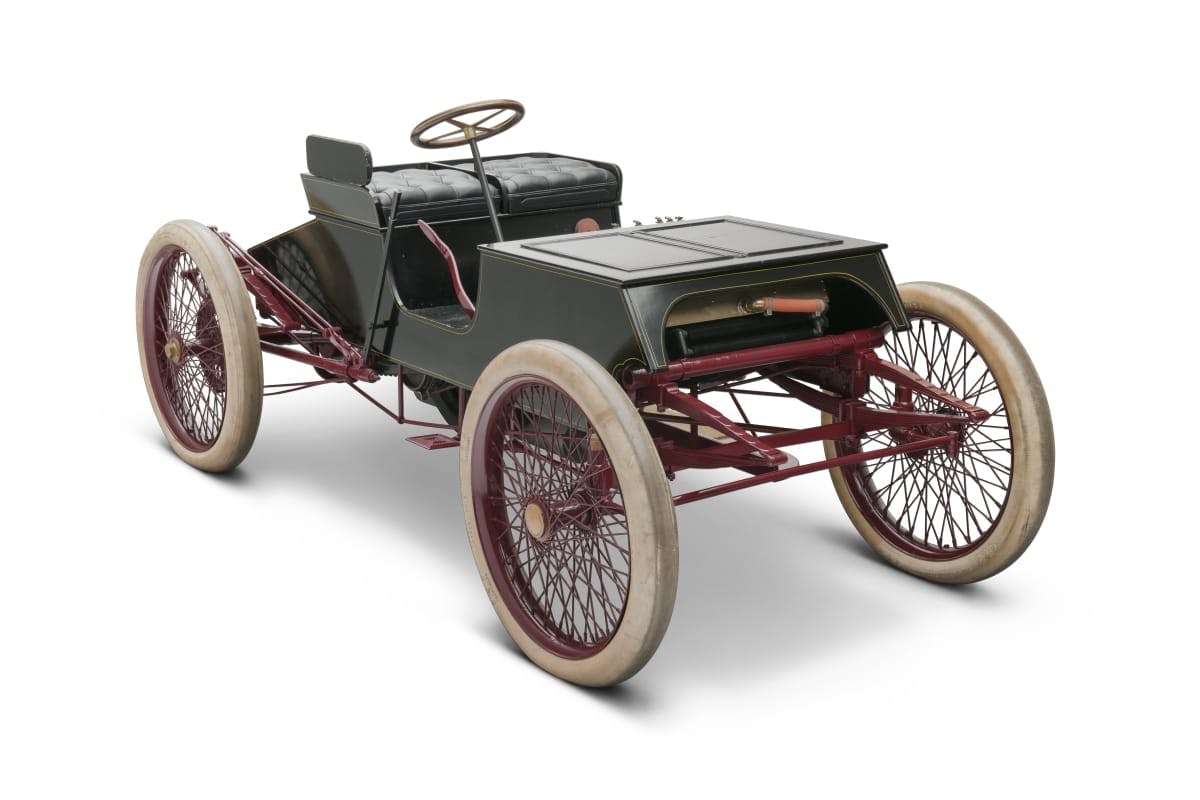

In 1901, shortly after dissolving his Detroit Automobile Company, Henry Ford challenged Alexander Winton to race around a one-mile horse track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. Winton, a Cleveland-based car maker and the favored entry, seized an early lead. Driving “Sweepstakes,” a car designed by his partner Oliver Barthel, Ford hung in with his riding mechanic Spider Huff leaning into bends to help maintain the cornering line.

On the fourth lap, smoke began pouring out of Winton’s exhaust. Ford gunned his two-cylinder, 26-hp engine to pass his opponent, averaging 44.8 mph for the 10-mile race. In addition to $1000 in prize money, Ford took home a lovely crystal beverage bowl with matching cups.

A month later, Ford used this new-found cash and notoriety to establish his second enterprise, the Henry Ford Company. Unfortunately disagreements with investors led to his departure after only a few weeks. But this time, thanks to Henry Leland’s reorganization efforts, Ford’s start-up survived. In August 1902, the Cadillac Motor Company rose from the HFC’s ashes.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

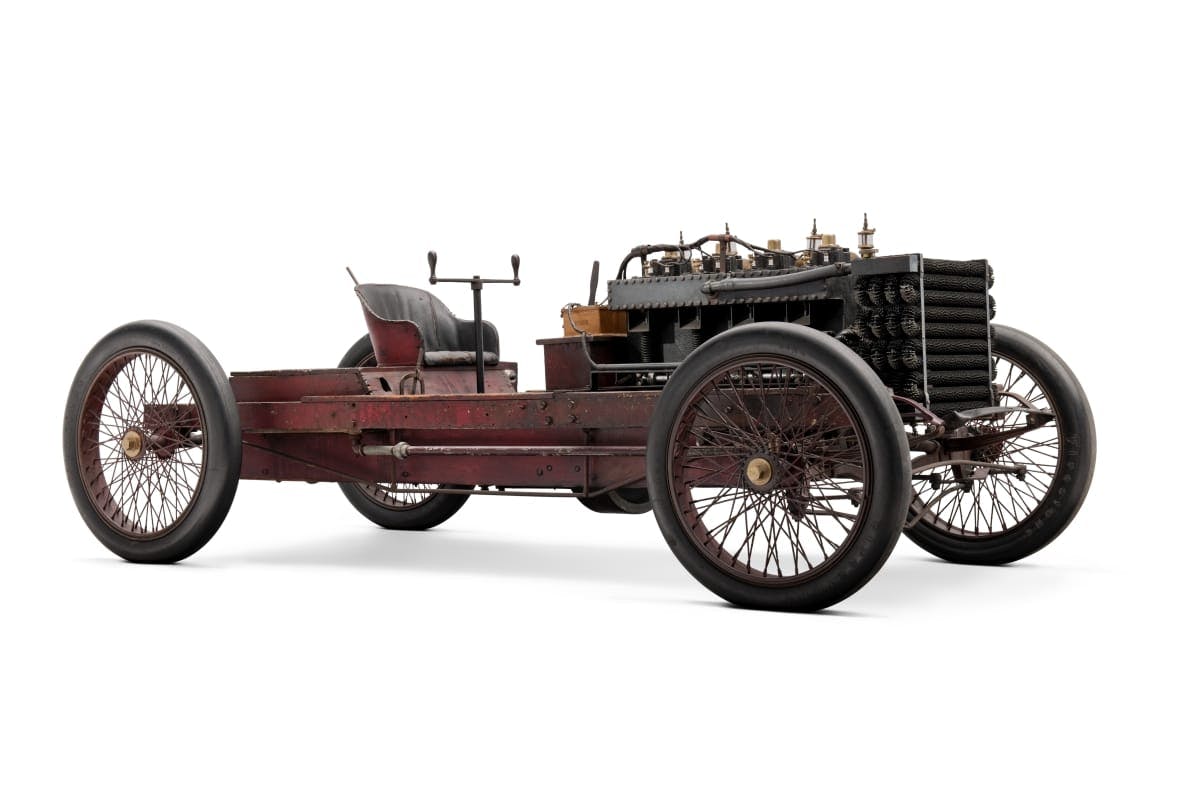

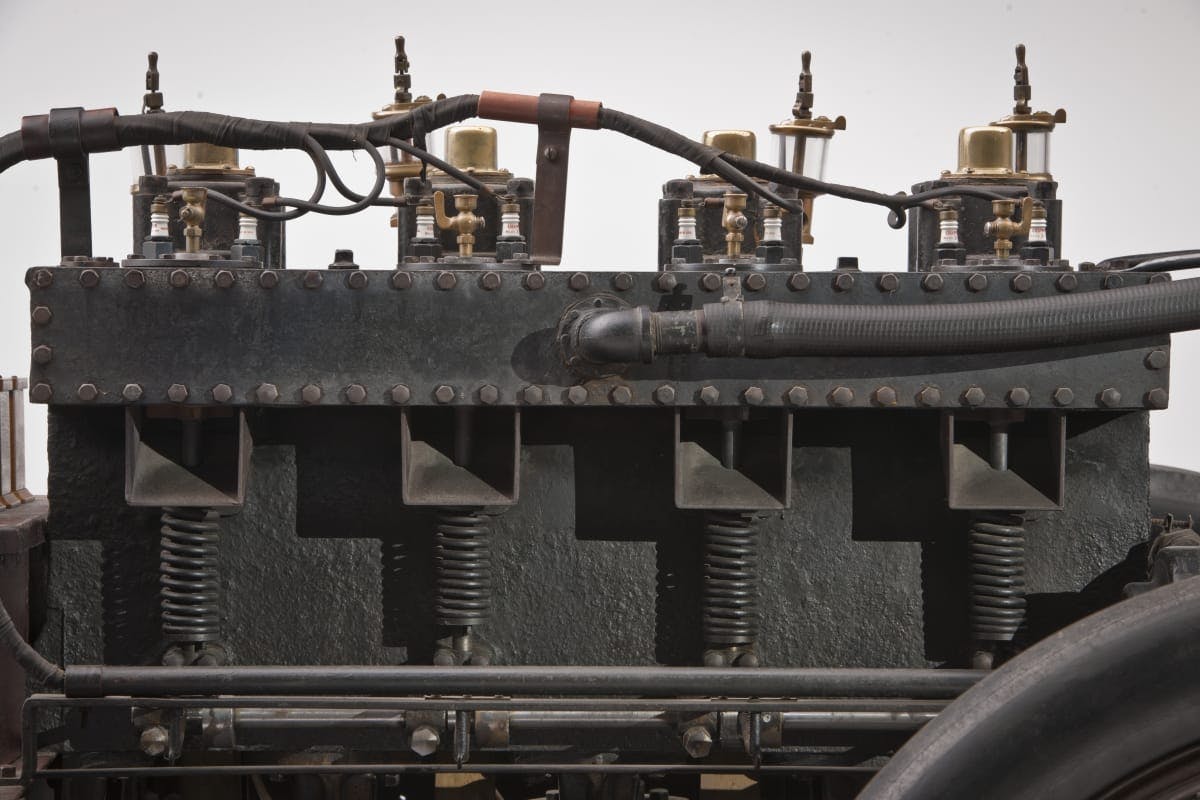

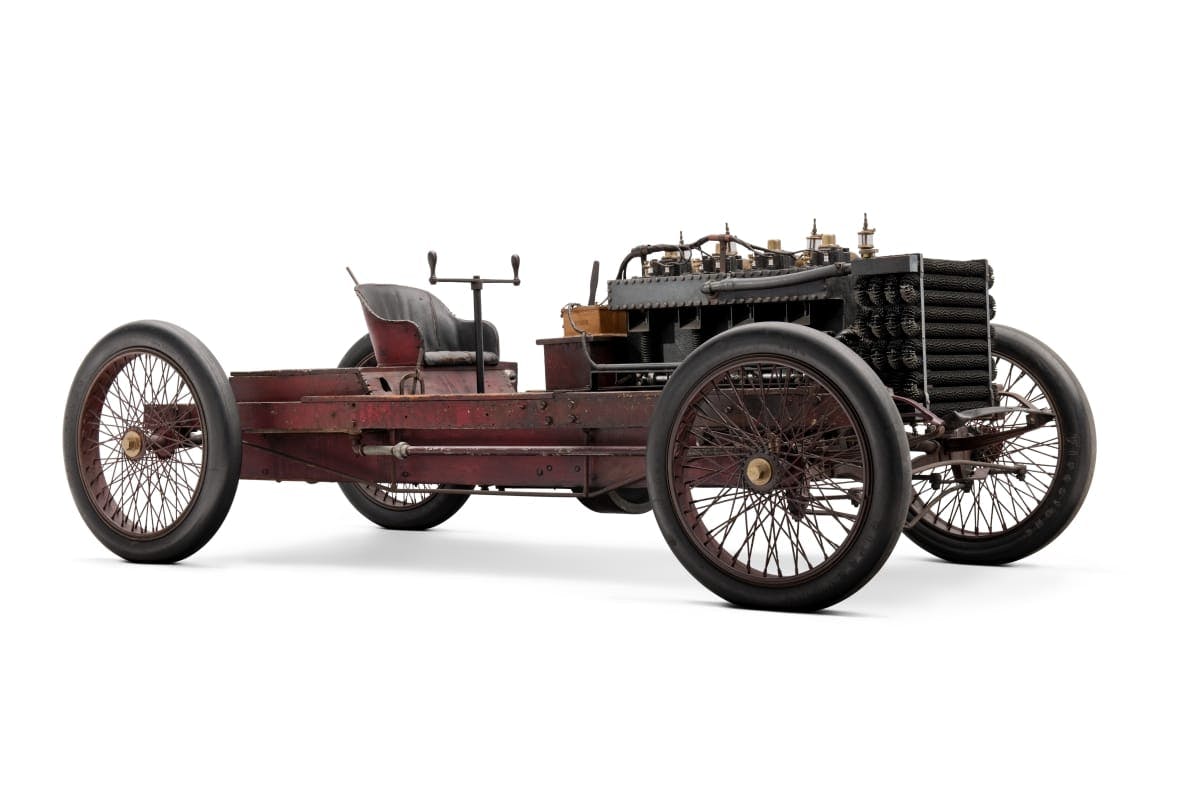

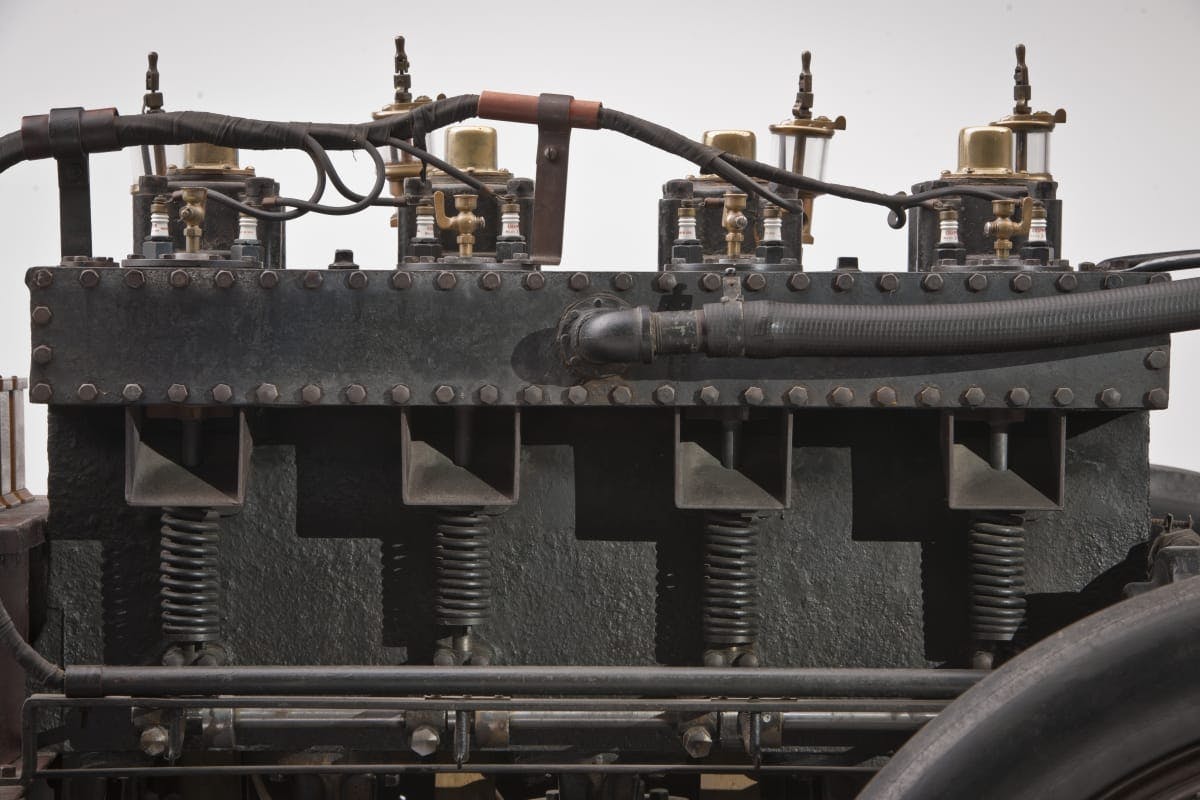

By then Ford and his colleagues had a more ambitious racing enterprise under development to challenge the 69.5-mph land speed record set by Frenchman Henri Fournier on New York’s Coney Island. Ford’s four-cylinder monsters—one called “999,” after a speedy locomotive, the other dubbed “Arrow”—produced 70–100 horsepower. Ex-bicycle racer Barney Oldfield was recruited and trained to drive the racers, which he described as “an engine on four wheels with brute strength but none of the qualities of a modern automobile.”

The resulting October 1902 race pitted the novice Oldfield in 999 against a never-say-die Alexander Winton and two other competitors. It was déjà vu all over again; when his car misfired on the fourth lap, Winton dropped out and Oldfield prevailed with a 54.9-mph average. Oldfield’s distinction as the first driver to lap a one-mile oval in less than a minute quickly spread. He ultimately won 20 or more races in Ford’s racers before retiring at age 40 in 1918.

After founding the Ford Motor Company in June 1903, Henry’s attention again ventured toward motorsports. The Arrow racer was shipped back to Dearborn for reconstruction in preparation for a land-speed-record attempt across Lake St. Clair’s Anchor Bay. Once that inlet iced over, a three-mile-long course was marked and groomed for attempts to top the existing 76.6-mph record held by Henri Fournier, driving a French-made Mors. Since Oldfield now drove for Winton, Ford took the driver’s seat with the ever-faithful Huff along to help hold the throttle open over the bumpy surface.

On January 12, 1904, Ford’s Arrow bounced off snow banks a few times before crossing the finish line with a record-smashing speed of 91.4 mph over one mile. What the two-man crew neglected to prepare for was stopping from such velocities. Their brakes were rudimentary, and there was inadequate distance to slow their 2730-pound monstrosity. To avoid colliding with a schooner locked in the ice, the wily Ford spun his Arrow into a nearby snowbank.

Ford’s success as a speed merchant again helped his budding Motor Company gain traction. Unfortunately, his reign as the fastest man on earth was fleeting. On January 27, 1904, on Florida’s Ormond Beach just north of Daytona, William K. Vanderbilt, one of the world’s richest men, drove his 90-hp Mercedes a mile in 39 seconds, raising the land speed record to 92.3 mph.

Florida beaches were first identified as the ideal place to worship the velocity gods in 1902 when Alexander Winton and Ransom E. Olds drove their latest creations there. Two years later, Ford and his wife, Clara, were on hand to witness the loss of the speed record he held only 15 days. A driver was hired and the Arrow was readied for shipment south to defend the Ford Motor Company’s honor, but that effort never bore fruit.

In 1905, Ford’s new six-cylinder Model K did venture south to meet the boss, residing in a tent and subsisting on cheese and crackers until funds arrived to mount his speed runs. Meanwhile, the record was lifted to 104.6 mph by a Napier, then to 109.7 mph by a twin-engined Mercedes. Realizing that this was beyond the reach of his Arrow, Ford headed north for summer beach racing in New Jersey.

The course at Cape May, New Jersey, wasn’t that fast, suiting Ford just fine. The top runners included A.L. Campbell, who achieved 94.7 mph in an 80-hp Darracq, and a 120-hp Fiat driven to 91.4 mph by Swiss mechanic Louis Chevrolet. Chevrolet went on to beat Barney Oldfield three times in 1905. The best Ford could do before 20,000 spectators in his 60-hp Model K was 90 mph. Failing to earn enough funds to pay his way home from New Jersey, he was forced to sell his Model K on the spot for $400.

This 1905 confrontation was the first and last time Henry Ford took on Louis Chevrolet. The next year, Ford hired Frank Kulick, one of his company’s first five employees, to drive a Model K tuned to 100 hp for the Ormond Beach speed week. The best Kulick could do in qualifying was 90.0 mph, versus Chevrolet’s 117.6 mph in a Darracq. Worse, Kulick spun out in a 30-mile race for American touring cars and Fred Marriott boosted the land speed record to 127.7 mph in a Stanley Steamer.

Rising velocities prompted Florida locals to consider a permanent course unimpaired by the vicissitudes of tides and erosion. Bill France Sr. (yes, of NASCAR fame) started competing there in 1937, when the course was a mix of beach sand and a portion of concrete highway adjoining it. France also saw the need for a better track: It took another 20+ years for his 2.5-mile paved Daytona Beach oval to come to fruition.

Louis Chevrolet and his two younger brothers, Arthur and Gaston, gained sufficient fame as race car builders and drivers that they drew the attention of William C. Durant, who had founded General Motors as a holding company before leaving that enterprise in 1910. The success of the Chevrolet Motor Car Company, established the following year, enabled Durant to regain controlling interest in GM by 1917. But by then, Louis Chevrolet was long gone.

While Chevrolet’s next attempt at car building, the Frontenac Motor Company, ultimately ended in bankruptcy, he did compete in four Indy 500s with cars he designed, with a best finish of seventh in 1919. His brother Arthur also ran two 500s and his brother Gaston won the 1920 500 race driving a Frontenac. Following his death in 1941, Louis was honored for his motorsports contributions with a memorial erected near the Speedway Hall of Fame Museum.

Upon the introduction of his wildly successful Model T in 1908 and the opening of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway the following year, Ford helped his driver Kulick earn victories around the country in stripped and reworked Fords. When he filed an entry for the 1913 Indy 500, officials insisted that 1000 pounds be added to the Model T. Ford’s apt response was, “We’re building race cars, not trucks,” and he promptly withdrew his entry.

Citing dissatisfaction with trivial rules and classifications, Ford imposed a moratorium on motorsports that lasted more than two decades. With his plate full building cars to suit overwhelming demand, there was no need for racing-related publicity.

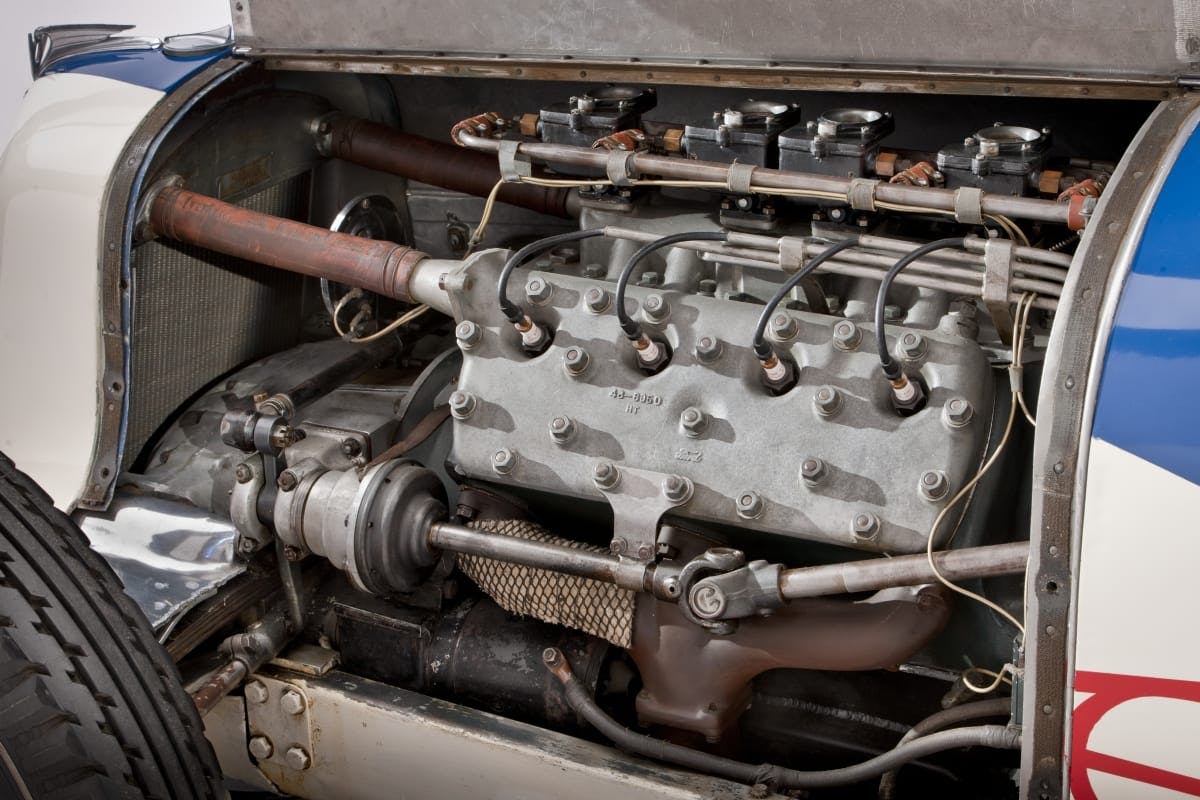

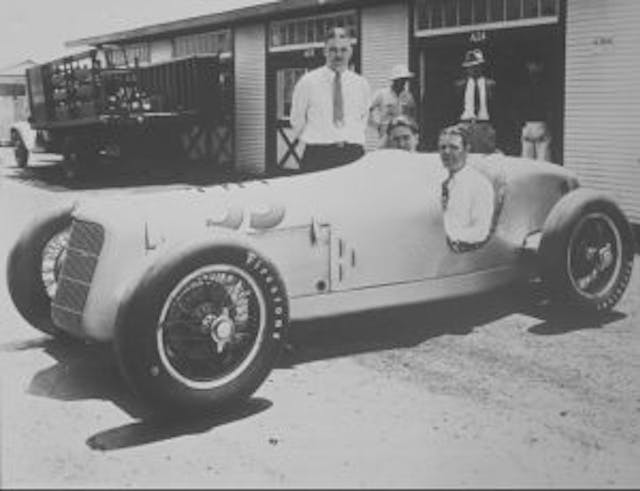

Shortly before the 1935 Indianapolis 500, Ford’s son, Edsel, teamed with the brilliant Harry Miller and promoter Preston Tucker to build no less than 10 racers with front-wheel drive, fully independent suspension, and flat-head V-8 power. To make the ’35 race, Ford engineers toiled 12 hours a day, seven days a week. Half the fleet was finished in time for qualifying and four of these striking racers lapped between 110–113 mph to qualify for the race.

Unfortunately, these Miller-Fords suffered a design flaw. A universal joint connecting the steering shaft to the pinion shaft was positioned too close to the left exhaust manifold. Heat build-up during the race resulted in u-joint failure and a total loss of steering control. After all four entries DNFed, a disgusted Henry Ford locked them away in storage in Dearborn. One car later finished third at the speedway, powered by an Offenhauser racing engine. In 1947, the Granatelli family ran a Miller-Ford with a Ford V-8 to 12th overall.

The Chevy-versus-Ford rivalry that began in 1905 quickly achieved immortal status. Today, there is no greater battle throughout the car business and motorsports. Honing their products to win has elevated both brands to the auto industry’s highest plateau.