Media | Articles

Exit via sunroof, and other tips to reorient the microcar novice

It’s pretty clear that any sane, modern-day driver who pays five figures for a silly 1950s bubble car doesn’t plan to drive it outside their over-55 gated community in Arizona. However, as someone who lived in the U.K. during the original age of the microcar, when it was simply a logical form of daily transportation, I have some wisdom to pass on to contemporary bubble-car owners. (Sense of adventure not included.)

These almost-cars found favor after WWII in a Europe which had been devastated, an era in which life moved much more slowly—often painfully so, as economies rebuilt from war. Rationing continued in the U.K. until July 4, 1954. Bombed-out building sites dotted major cities, industry struggled to get back on its feet, and thousands of returning troops searched for non-existent jobs.

“And to think we WON!” said my puzzled father as he cycled around Southeast England looking for steady work, meanwhile filling in with jobs such as a barker at Margate’s Dreamland carnival. “Step right up, ladies and gennlemen, boys and girls. Everyone’s a winner!”

In due course Pop found work as a draughtsman with the Ministry of Defense in Folkestone and graduated to a Solex-style motorized bicycle to commute to the base about five miles away. That served him well—except for the time I thoughtfully topped off his gas tank from the garden hose. In due course the bicycle turned into a 1950 Douglas Vespa 125cc scooter, then a Francis Barnet Plover 150cc motorcycle, and finally a 1949 Panther motorcycle combination with a Canterbury sidecar. We didn’t get a real car until our 1954 Hillman Minx station wagon in about 1958. If that counts as a real car, that is.

In the meantime, the strangest collection of half-pint tuk-tuks were cluttering the slow lanes in our seaside town. They were powered by two-stroke engines of dubious origin which definitely weren’t meant to operate in a confined space for very long—and they didn’t. By the time I was old enough to buy anything that moved (I had a low bar), such vehicles were like butterflies which had woken from a nap to discover was December.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

At least the names were musical: Berkeley, Bond Bug, Goggomobil, Heinkel, Meadows Frisky Sport, Messerschmitt, Piaggio, Powerplus, Reliant, Scootacar, Velorex.

My brother and I owned a number of “walking wounded” vehicles. Rather than write an enthusiast’s glossy memorandum, allow me to share some lessons we learned.

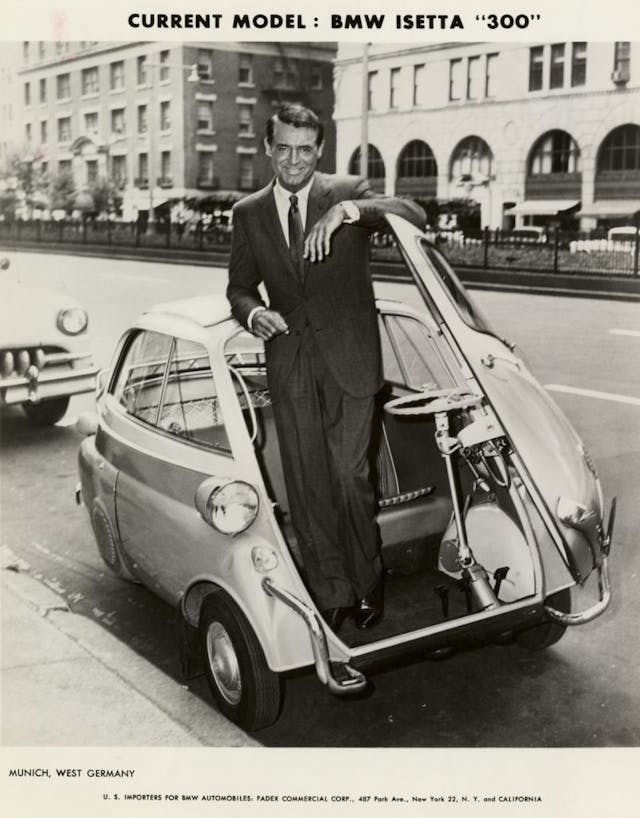

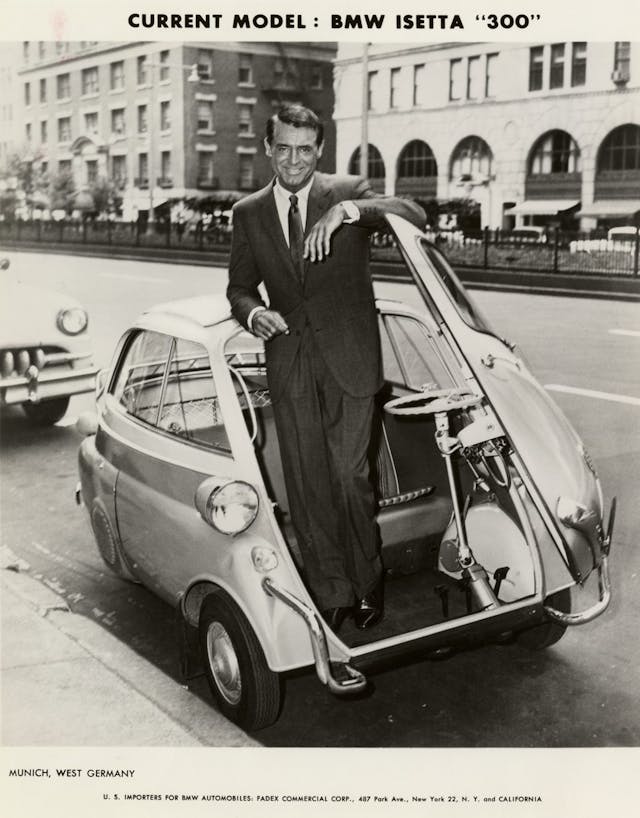

If you buy a 1959 BMW Isetta 300 and survive your first terrifying drive home in rush hour, be mindful of the following: If you’re going around a corner fast and the steering wheel starts twitching in your hands, it’s because the inside front wheel is about to lift off the ground. When it does, you will probably roll over, perhaps down the sidewalk on Surbiton High Street on a Saturday morning, scattering pedestrians.

If you come to a stop on your roof against a hairdresser’s window, you will not be able to open your front door because it opens upwards—and is now facing downwards. The trick is to rock sideways back and forth until (a) the car rolls onto its side or (b) two people push you upright, when they stop laughing. If you are lucky the engine will still be running, and you can sneak away before the constables arrive.

Other tips on Isetta ownership: Top speed is 54 mph—on the level. If you notice a sudden surge of power, reaching 60 to 61 mph, look at the ignition light. If it glows red, the Seib Dynastart (which doubles as starter AND generator) has succumbed to an oil leak from the main seal and is no longer a drag on the engine. Wherever you are, head for home, where you can pull off the engine covers and clean the brushes.

If your muffler has rusted out, DO try and get the right one. It’s heavy and the pipe runs forward, then back through the muffler. Do NOT succumb to the urge to fit a Burgess motorcycle silencer facing backwards because it (a) looks good and (b) sounds great. Why? There is nowhere to anchor it at the rear.

If you attach it to the body, the bracket will break or the sheetmetal will split. If that happens the muffler will fall off. If it does, do NOT hop out and pick it up—especially if you are wearing gloves because it is cold out and the heater is pathetic. If your gloves are synthetic (e.g. vinyl) they will attach to the hot muffler. As you realize that and drop it, they will stretch away from you, like Plastic Man.

Speaking of cold weather, warm the car up thoroughly on a frosty day. Do not figure that, oh, the windows will clear off soon enough. They won’t, and if you are unlucky, you will arrive at a junction at the same time as another car with right of way. If so, it could coast in front of you just as you set out behind your foggy glass.

Some Isettas have vertical loop bumpers on each front fender. These can be bent in a collision, pinning the front door shut and forcing you to exit through the sunroof.

If you need to get under your Isetta—to fix a clamp on the clutch cable for example—find a nearby lamp post, take off your jacket and lean the car against that stalwart bit of civil engineering while you repair the clamp.

Finally, DO NOT attempt to bump start an Isetta by yourself. While the car is easy to push, once it gets going downhill, it is virtually impossible to run around from the left side to the right front, open the front door, jump into the driver’s seat and grab the wheel. There is a very real possibility the car will run over your foot. When you fall down, it will go wherever it pleases—with catastrophic results.

I am indebted to my brother Phil for the next piece of advice, which applies to Bond Model D minicars. He had one in grammar school, in a fetching baby blue. The Bond had a 197cc, single cylinder, two-stroke engine which turned a front wheel in between two dummy front fenders. There was enough room under the hood that the motor could turn 90 degrees, obviating the need for a reverse gear. You just turned in your own length.

The starter motor worked like a lawnmower’s. A lever on the floor was attached to a piece of rope, which was wrapped around a pulley on the end of the crankshaft. If the rope broke, you could open the hood and use the kick start on the side of the engine. The rear suspension depended on the air in the 8-inch tires. But if you did get a flat tire, at least you could pick up the rear to change the wheel.

Phil drove it everywhere flat-out, which translated to roughly 50 mph. Since it was aluminum, that was quite possible, but after a while a large number of loose rivets rattled around on the floor! The worst thing about the Bond was the visibility—near-zero—through the side-curtains when the top was up. Once, Phil was easing out onto a four-lane highway, craning his neck to see if a car was coming. It was. A Morris Minor hit him at about 45 mph, slicing off everything ahead of the firewall and flipping Phil’s car several times. Amazingly, he was not hurt—but the Bond was removed from the scene in two pieces. I never could find the front part in the wrecking yard.

So be careful out there, microcar people. Remember, you will be small—but slow.

My best friend used to have an Isetta powered by a Honda 750cc V4 motorcycle engine. Can you say “Dangerous”? The car still had the stock 7″ drum brakes, and trying to stop that thing from the wayyy higher speeds it was capable of was a death-defying experience. Still it was pretty fun to drive!