Media | Articles

The father of Cord was a Gatsby-era genius

When the Cord 810 was unveiled at the New York auto show in early November 1935, it created a maelstrom of interest among the press. The New York Daily News called it “revolutionary” and noted that it was “one of the hottest looking, most distinctive cars that has made its appearance in a long, long time.” The Brooklyn Times-Union noted “its extraordinary design.” And the Los Angeles Times, in a story with the headline “A Car Unlike Any Other,” called it “radically different from any other motor car that has ever been offered to the public. Ultra-modern in appearance and greatly advanced mechanically, the new Cord will unquestionably set a trend affecting motor car design for many years.”

Public reaction was strong as well. Reporters described show attendees at the Grand Central Palace standing recklessly on the running boards and the hoods of nearby display cars. The Brooklyn Times-Union said that the car “drew many admirers,” singling it out as a magnet for the 40,000 people who had attended the show. Orders poured in. Cord’s charismatic founder, Errett Lobban “E.L.” Cord—who, at 31, was the youngest chief automotive executive in history—also controlled the innovative Auburn and Duesenberg car brands along with dozens of other manufacturing entities. He promised customer deliveries by Christmas of that year, just six weeks away.

The acclaim was understandable. The 810 was an intensely sophisticated piece of design and engineering from a company known for pushing forward in both fields. It capitalized on the radical front-wheel-drive technology Cord had pioneered in American production vehicles in his L-29 of 1929—which itself relied on technology that Cord had licensed from race car driver Henry Miller, whose front-drive car scored multiple Indianapolis 500 victories in the 1920s. And it included a compact but robust V-8 engine, produced by Lycoming, another Cord Corporation subsidiary.

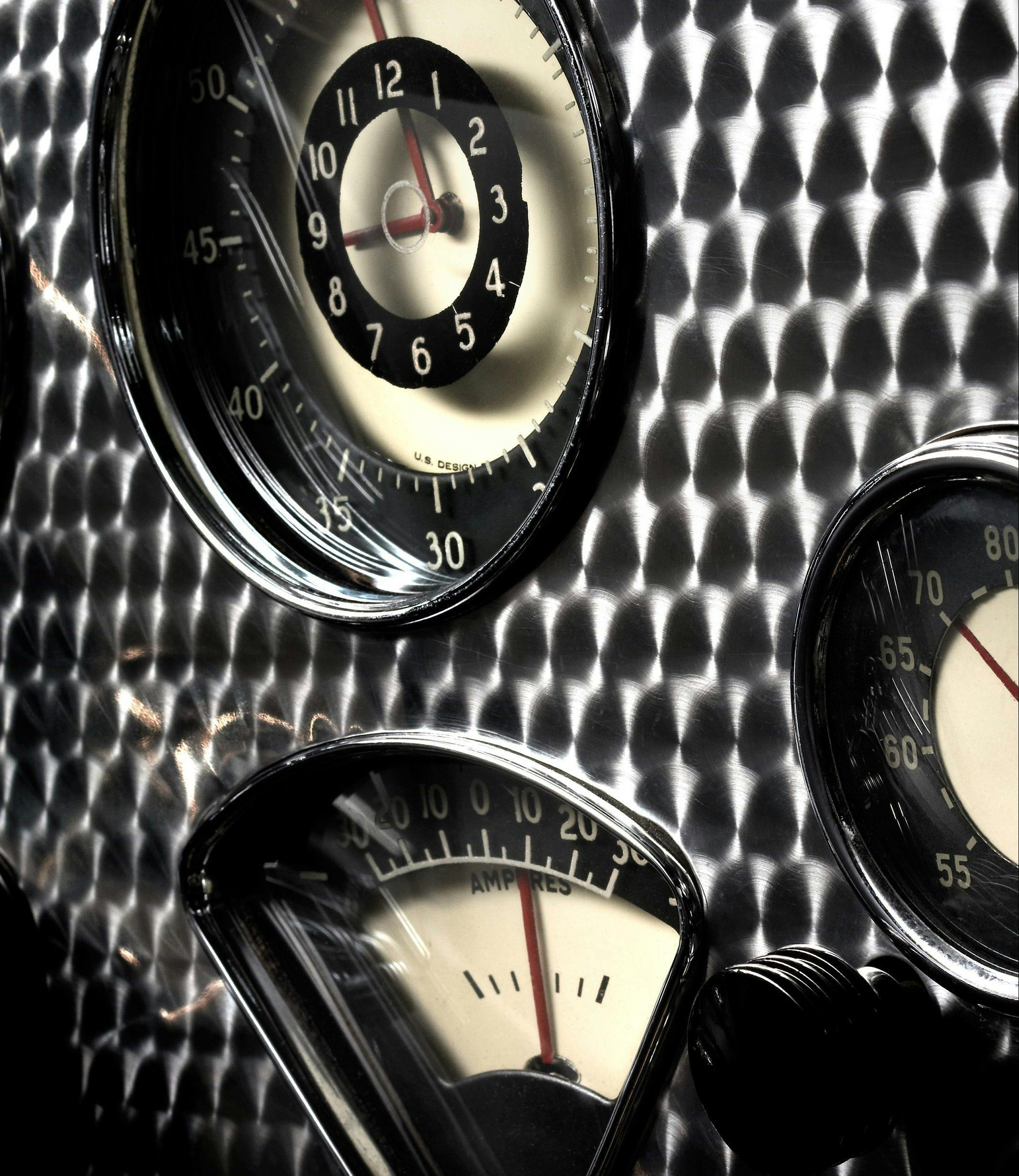

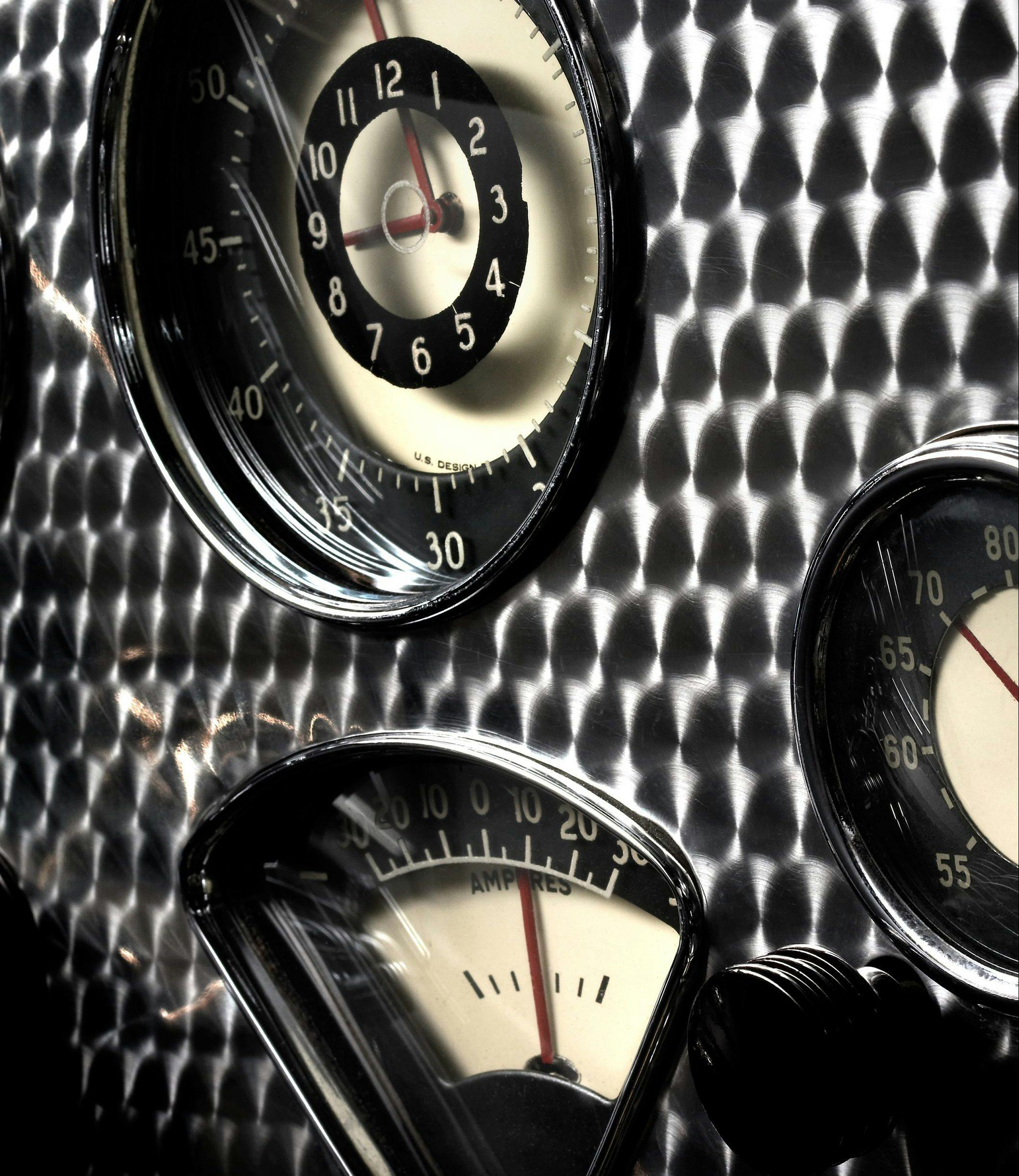

This layout, with no driveshaft or transmission tunnel, allowed the car to have a flat interior floor as well as an independent front suspension. The rakish looks came from its low ride height and low overall height—just 58 inches in convertible form, when a new Ford was nearly a foot taller. The low ride height allowed the Cord to do away with running boards, necessary for stepping up into taller vehicles. It was also the first car with a hidden radiator, accessed by the industry’s first rear-hinged (instead of side- or center-hinged) hood. The Cord could also lay claim as the first with a hidden fuel-filler cap, hidden door hinges, and hidden headlamps; little cranks on each side of the dash rolled them up out of each front fender.

Penned by Gordon Buehrig—who had already serviced Cord’s other brands with the stately 1929 Duesenberg Model J and flashy 1935 Auburn 851 Boattail Speedster—the 810’s styling was impossibly streamlined, with a recumbent windshield, prominent pontoon fenders framing a louvered grilleless hood, and a tapered teardrop-shaped rear.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The car exemplified Cord’s genius. “He was a visionary and an entrepreneur, very forward- and future-thinking,” says Sam Grate, curator of the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum, housed in the old Cord Corporation automotive headquarters in Auburn, Indiana. “As well as hiring an excellent support cast of engineers, designers, and more, which added to this perfect equation where the outcome was innovative and futuristic.”

The press clamored that, perhaps, this was the comeback that Cord Corporation needed in order to stanch the bloodletting in its core automotive properties. Although the overall automotive market, after reaching its nadir in 1932, was rebounding significantly, volume leader Auburn was tanking, and ultra-luxury marque Duesenberg was struggling to remain relevant. Likewise, the Cord could not pull through. “It was a bit ahead of its time,” says comedian and car collector Jay Leno, who owns an Auburn, a Cord, and eight Duesenbergs. “And there were a lot of teething problems with it.”

Cord couldn’t meet his end-of-year delivery deadline and sent waiting customers bronze mini replicas of their missing cars. The consolidating energies of the industry, and its Big Three players, took this lull to attack Cord’s radical creation as a dangerous death trap, christening the 810 the “Coffin Nose.” Cord rushed the cars out in mid-1936 before they’d been completely shaken down, shipping out vehicles haunted by problems that included sticky transmissions, overheating radiators, and underperforming universal joints.

The 810 was striking and sophisticated, and Cord reveled in advertising it to potential consumers. “A Champion Never Pushes People Around,” read a period ad in The Saturday Evening Post, trumpeting the car’s pulling front-wheel-drive layout. But after seven or eight years of the Depression, the public had lost its appetite for this kind of flash and newness. Within a year, the entire Cord Corporation was dissolved, and the automotive brands E.L. Cord founded disappeared from the new-car market.

***

Errett Lobban Cord was born in July 1894 in Warrensburg, Missouri, about 60 miles southeast of Kansas City, the son of a shop owner. The family moved to Los Angeles when E.L. was 10, and he attended school there, including a few years at L.A. Polytechnic High, but he dropped out at age 15 to pursue his interests. As a teenager, he found jobs selling or transporting cars or working in construction-related fields, but in 1913, when he was 18, he started painting, modifying, and reselling old Ford Model Ts.

This was before the advent of the term “hot-rodding,” but that is precisely what Cord was doing, adding higher compression engines, better radiators, and bigger carburetors to the tin lizzies, while stripping away body parts to further enhance their power-to-weight ratio. Cord raced these cars on the dirt and wooden tracks of the day because he loved speed, but also because he realized that winning cars could be sold for bigger profits. He would buy cars for $75, soup them up, race them, win, and sell them for five or 10 times as much. By 1914, he’d sold more than 20, profiting at least $500 on each one.

In the 1910s, Cord ran an ore-hauling company in the Arizona desert, worked as a car salesman for the Paige brand in Phoenix, had a one-car rental car agency and one-bus stage line in L.A., and tried to develop a portable gas-powered heater. He went broke repeatedly. Then, in 1920, he got a job in Chicago with car distributor/dealer John Quinlan selling the expensive St. Louis-built Moon. He was wildly successful, expanding Quinlan’s territory and eventually claiming the franchise for Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.

Being a salesman was his core achievement—knowing what people wanted and how to deliver it to them. His biographer, Griffith Borgeson, in his book Errett Lobban Cord: His Empire, His Motor Cars: Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg, described Cord as “having a mentality which understands human tastes, wants, and needs so well as to be able to invent the products to satisfy them, and even the organizations to produce them.”

By 1923, having saved the then-princely sum of $100,000, he decided he wanted to start his own car company. Quinlan introduced him to a consortium that controlled the Auburn Automobile Company, a failing Indiana manufacturer that traced its roots back to the Eckhart Carriage Company, set up by an ex-Studebaker wheelwright in 1874, and which had produced its first one-cylinder motor car around 1903. The company had fallen on hard times in the era of industry consolidation that followed WWI.

The board offered Cord a job managing sales and manufacturing, but he wanted more. Stories differ on what he demanded and what the board countered, but the general consensus is that he suggested that he could turn the company around, sell its existing backlog of 1500 outdated cars, and have a new model in production by the following year. If he succeeded, he wanted complete control, a portion of the profits, and enough stock options to buy a controlling interest in the company. The board accepted.

Cord managed to dump much of the old stock and moved on. He developed a new, sporting model, featuring a straight-eight Lycoming motor, providing an affordable car with an engine that, until that time, had been the exclusive province of ultra-luxury marques like Packard and Duesenberg (where it originated). It was a big hit at the 1925 New York auto show. Having fulfilled all of his obligations, the 31-year-old Cord took over as president of Auburn.

Wanting to expand further, in 1926, Cord set his eyes on Duesenberg Automobile and Motors Company. Founded by the brilliant racing engineer Fred Duesenberg and his brother August, the company’s goal was to build Indy-winning race cars and engines, followed by sporting consumer vehicles. Duesenberg had innovated with the world’s first straight-eight motor, the first four-wheel hydraulic brakes, and the first centrifugal supercharger, but it was foundering and nearly bankrupt. Cord bought it with flourishing Auburn stock and gave Fred the task of engineering the best car in the world, capable of competing with Rolls-Royce and Hispano-Suiza.

“Duesenbergs were a bit staid and boring-looking,” Leno says. “They didn’t have any flair, they weren’t sexy, but they were advanced cars. Cord walked in and said, ‘I want you to build the biggest, fastest, most powerful American car.’”

Announced in December 1928, that car was the Duesenberg Model J. Like the contemporary Bugatti Chiron, the J was to be offered in an extremely limited edition of 500. It hosted the most potent and advanced engine of the time. When a top-of-the-line Cadillac was making 95 horsepower, the double-overhead-cam, four-valve-per-cylinder Duesy straight-eight made a whopping 265 horses (320 in later supercharged trim, nearly 400 in special configuration). The company sold only complete rolling chassis, farmed the design work out to Gordon Buehrig and the best coachbuilders of the day, and charged customers orders of magnitude more than other cars.

“When a Ford was $260, a Duesenberg was probably $10,000 just for the chassis,” says Leno. “Duesenberg was flashy. Duesenberg was for the Gary Coopers and the Clark Gables, and the guy who wanted to make an entrance—kind of the way a Lamborghini owner would be today. You know, kind of the gold-chain set.”

The effort was successful; by 1930, the company had sold 250 of the highly profitable cars, even during the depths of the Depression. The ultra-rich, royalty, and the new Hollywood elite had to have a Duesenberg.

The Cord magic worked on his other brands as well. While national car production declined by nearly 60 percent from 1929 to 1931, Auburn sales went up from 13,000 to 31,000. Cord’s midrange eponymous nameplate sold over 5000 of its aforementioned front-drive L-29s, based mainly on their handsome, rakishly low profile. “He was building his version of General Motors,” says Leno, of Cord’s trio of marques.

He was building a vertically integrated transportation empire, too. He acquired Lycoming in 1927, to provide engines for his Auburn vehicles. That year, he also acquired Ansted Engineering and Lexington Motor Company, a manufacturing site in Connersville, Indiana, and started building closed Auburns and later Cords there. In 1929, he acquired the Limousine Body Company of Kalamazoo, Michigan, and built convertible Auburns and Cords there. That year, he also acquired the Columbia Axle Company, a body and engine manufacturing facility in Cleveland, as well as Stinson Aircraft, a small plane manufacturer in Michigan.

Provided with Lycoming engines from Cord Corporation, Stinson soon became the leading manufacturer of commercial airplanes, with unit prices so low that it pushed even Henry Ford out of the category. Cord started two commercial airlines, Century and Century Pacific, sold them Stinson planes with Lycoming engines, and flew routes—and delivered precious federal air mail contracts—from the Midwest to the West and throughout the West Coast, undercutting railroads in ticket prices. He even built seven-passenger Auburn sedans on a stretched wheelbase to use as airport shuttles for his airlines. Checker Cab and a big chunk of the Kansas City Southern Railway were acquired in 1933, along with the New York Shipbuilding Company—just the day before, a $38.5 million Navy contract came through.

Additionally, Cord diversified into Southern California radio station KFAC, as well as an ever-increasing portfolio of Beverly Hills real estate. He hired pioneering African American architect Paul Revere Williams to design for his growing family a grand 16-bedroom, 32,000-square-foot home on a 9-acre plot in Beverly Hills, which he named Cordhaven. Time magazine put him on the cover in 1932 and again in 1934, when it called him “Mercury to the Masses” and referred to him as a “purveyor of cheap speed on land and in the air.”

All of this wheeling and dealing attracted the attention of the newly founded Securities and Exchange Commission, set in place by Franklin Roosevelt to prevent the kind of stock market manipulation that was both standard at the time and one of the causes of the crash of 1929. Cord was made an example and investigated repeatedly for questionable dealings in Checker Cab stock, as well as that fortuitously timed Navy contract.

In the midst of this, his car business began to contract. Auburn sales plummeted, and the Cord 810 could not be saved by the introduction of an optionally supercharged variant called the 812. Duesenberg sales stalled, even after the introduction of a supercharged SJ variant, never reaching the promised 500 units. All three brands retracted from the market entirely in 1936 and 1937. The Duesenberg factory and land were sold to Marmon-Herrington. A Cadillac dealer from Chicago purchased 17 complete cars on-site for $18,000. The SEC found against Cord on August 5, 1937. The next day, he sold his Cord Corporation holdings for $2.5 million.

Cord went on to far more profitable careers in mining, radio and TV stations, aviation and home appliance manufacturing, and especially real estate—his Beverly Hills holdings sold for $10 million in 1948. Cord moved his family to various ranches in Nevada, where he owned 35,000 acres, and became active in state Democratic politics. He was elected a state senator of Nevada in the 1950s and was expected to run for governor, but he bowed out and didn’t accept the nomination; indications point to his fear of the mob, which, with the rise of the Las Vegas casinos, had infiltrated state government. When he died in 1974, he left an estate worth nearly $40 million.

His cars were never bestsellers, but they were, nearly to a one, memorable and notable. Cord loved speed, he respected engineers and designers, and he was generally cautious if sometimes reckless in his business dealings. But he was always prescient in his willingness to engage with forthcoming trends.

“Even back in the ’70s, he would say, ‘Why would anyone care about these cars?’” says Bill Cord Hummel, E.L.’s eldest grandson. “‘They’ve been gone for 30 years. You need to be forward-looking. Don’t be worrying about these old cars.’”

This thinking prevented E.L. from saving any vehicles from his empire. “He never kept the Auburns, Cords, and Duesenbergs,” Hummell says. “He said, ‘I sell them, I don’t collect them.’”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Cord was a visionary in the auto industry in design but really did it at the worst time possible in the economy. He also relied on new tech that was not always ready for prime time.

FWD and the Preselector transmissions were advanced but just not ready for the masses.

He did go on to other ventures but it never just was the same as the rest.

I believe it was his grandson Chis Cord who recently passed away that really made the Cord name in racing driving and winning for Dan Gurneys IMSA teams.

While the Cord it self did not change the world it did influence it much. I expect Harley Earls Show cars may have had more than a little ideas applied from the Cord. Hid away headlamps and low no running boards. Harley just took it even lower.

Great story