Media | Articles

Enzo Ferrari proved empires aren’t forged by the squeamish

Today, Enzo Ferrari graces the silver screen in a new biopic, titled Ferrari. The film recounts Enzo’s risky bet on the 1957 Mille Miglia, the 1000-mile sports car race whose outcome could determine the fate of his namesake company. In celebration of the big debut, which features Adam Driver, Penelope Cruz, and Patrick Dempsey (read our exclusive interview with the actor here) we’re resurfacing this October 2022 article. —Ed.

They called him the Old Man, Il Commendatore, or simply Mr. Ferrari. But Enzo is said to have preferred the title of l’ingegnere, the engineer. Few would argue that he deserved the label, though Enzo Ferrari washed out of technical school and only adopted the honorific after the University of Bologna conferred on him a ceremonial degree in 1960. It was just one pantomime in an operatic tale of struggle, cunning, triumph, carnage, and ego warfare that were the pillars of Enzo’s life and empire.

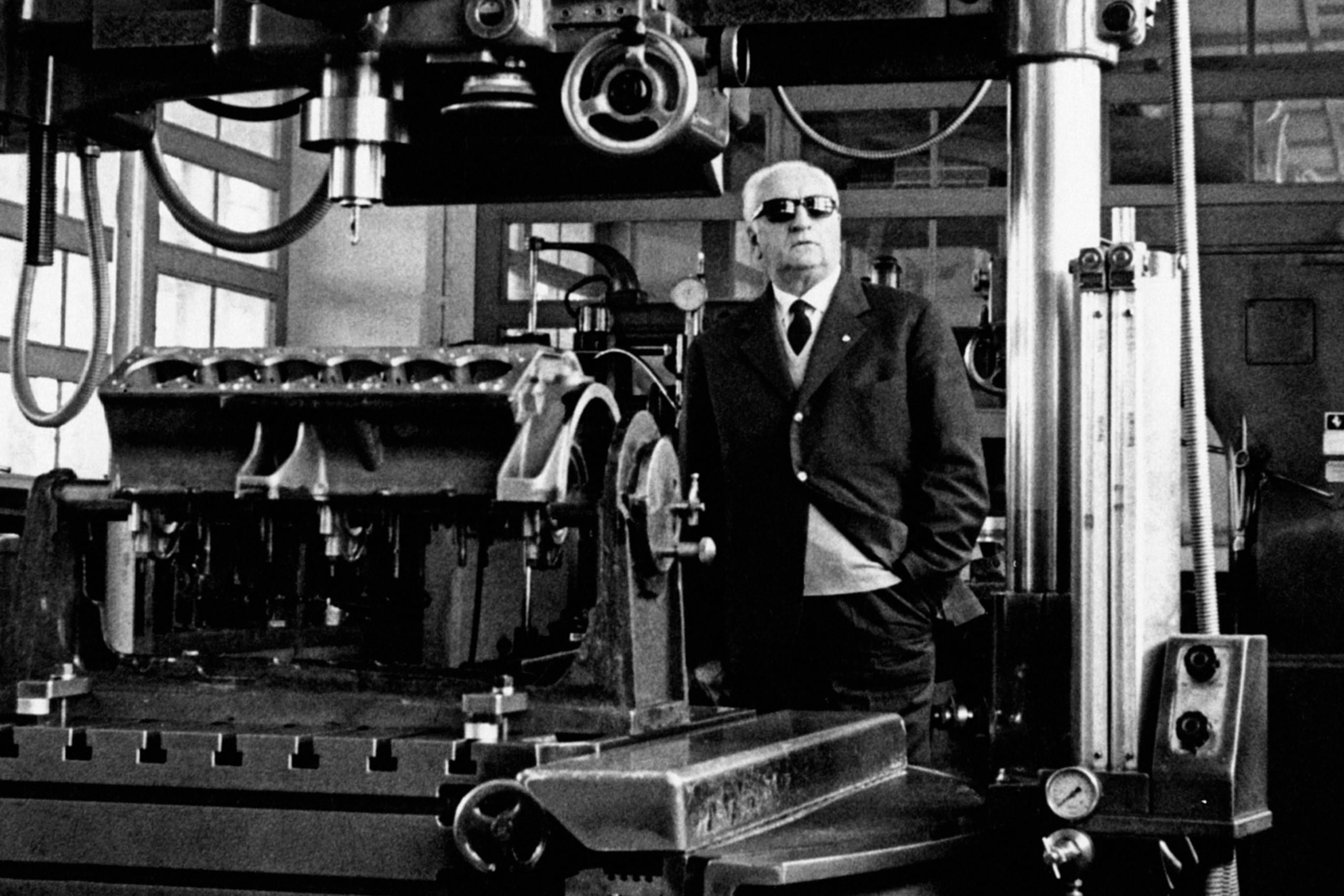

To outsiders, he was an inscrutable, 6-foot-2240-pound golem of stone hiding behind dark glasses. To insiders—at least those who wrote books about or spoke of their days in Ferrari’s orbit—he was an often-exasperating puzzle, a confusion of contradictions and emotions propelled by a bunker-like insecurity informed by a worldview firmly fixed in 19th-century Italian masculinity.

Was he a genius? Well, he knew brilliance when he saw it. In engineers, such as Vittorio Jano, Gioacchino Colombo, Giotto Bizzarrini, and Mauro Forghieri. In designers, from Battista “Pinin” Farina to Sergio Scaglietti. And in drivers, from Tazio Nuvolari to Juan Manuel Fangio to Mike Hawthorn to Phil Hill to John Surtees to Niki Lauda. He turned proud, ambitious, and gifted men into fawning supplicants willing to devote their careers and risk their lives for the splendor of the Scuderia. Then he often drove them out, or mad, or into early graves with relentless pressure tactics applied through endless political intrigues.

People said Enzo Ferrari preferred his cars and his mechanics to his drivers and his customers. According to Ferrari biographer Brock Yates, somebody once asked Luigi Chinetti—who cracked open the hugely lucrative American market for Ferrari—if Enzo deserved the reproach. After considering it for a moment, Chinetti replied, “I don’t think he liked anyone.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

It’s no accident that the history of Italy’s auto industry is largely confined to a crescent on a map defined by the Po River and the broad plain it bisects in Northern Italy. The region has been known for its metalworking since the Middle Ages and for its sophisticated design and engineering since the Renaissance. Enzo’s father was a metalworker, starting with a dirt-floor workshop next to a dirt-floor house in Modena, an ancient gray burg that swelters in summer and is often enveloped by a dismal, greasy fog in winter. When his second son, Enzo Anselmo Giuseppe Maria Ferrari, was born on February 18, 1898 (the exact day is a matter of dispute and speculation), Alfredo Ferrari was busy growing his business into a thriving workshop that supplied the national railway with bridge and canopy iron.

Though Enzo would claim later in life that he came from rags, his father bought the family its first car, a single-cylinder De Dion-Bouton, in 1903, when many Italians still dreamed of a donkey cart to call their own. Young Enzo’s romantic visions of his future drifted, from opera singer to Olympic sprinter to sportswriter. However, Italy, more than any other European nation, had gone mad for the automobile. Every region, practically every town, hosted a hill climb or a trial or a circuit race, and Ferrari was caught up in the fever.

World War I and the untimely death of both Enzo’s father and older brother, Alfredo Jr., or “Dino,” delayed events and decimated the family business. In November 1918, Enzo was rejected for a job at Fiat, sparking a grudge that would endure until 1969, when he extracted millions from the Agnelli family in exchange for Fiat’s half interest in Ferrari. However, rather than head home from Turin, Enzo started to pal around with the drivers and mechanics who infested the backstreet garages and pubs of Italy’s burgeoning motor city.

His results as an amateur racer drew the notice of the Alfa Romeo team, which invited him to join the squad as a journeyman driver in 1920. Despite modest success as a piloto, though, Enzo longed to return to Modena, where he saw more opportunity as an Alfa Romeo dealer and racing-team manager than as a driver, which was a filthy, bare-knuckled profession in those early days that routinely racked up a horrific butcher’s bill. Racing laurels brought fame, money, and women, but Enzo had an innate sense of both his limited driving talent as well as his true calling, which, given the bleak odds back then, probably saved his life. After he founded Scuderia Ferrari and began building his own cars in 1947, he rarely drove himself, preferring to be driven by his former riding mechanic and longtime valet and chauffeur, Peppino Verdelli. His fate was to wear a tie instead of leathers, to sit behind a desk rather than a steering wheel, and to die in bed at the age of 90 rather than against a tree or upside down in a burning wreck.

Seasoned racers say their chosen sport brings the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. Such was true of Enzo’s entire life, a melodrama of glory and bitter personal and professional grief, the latter often coming hard on the heels of the former as chronicled in his aptly titled autobiography, My Terrible Joys. For the most objective reading on Ferrari, see the two best biographies, Enzo Ferrari, the Man and the Machine, an amusingly sardonic take by the late Car and Driver editor and Cannonball Run founder Brock Yates, and Enzo Ferrari: Power, Politics, and the Making of an Automotive Empire, which, at nearly a thousand pages, is a more academic (and less deliberately iconoclastic) undertaking by Luca Dal Monte, a former Ferrari PR man.

One walks away with an impression of a figure who saw himself as a David constantly in battle with one Goliath after another for the honor of his little duchy of dedicated artisans and, by extension, Italy itself. From Nazi-funded Germans before the war to the chastened but still very potent Germans after, followed by his hated crosstown rival, Maserati. They were replaced by a band of British innovators such as Cooper and Lotus—Enzo dismissed them as the garagiste because they operated out of small garages and didn’t build their own engines—followed by the mighty Glass House presided over by a spurned and vengeful Henry Ford II. After Porsche arrived with 917s that could top 220 mph on the Mulsanne Straight at Le Mans, Ferrari retreated from sports car racing to focus its limited resources on Formula 1.

Subterfuge was a tool that never got rusty in Enzo’s box. In September 1953, he summoned the Modena police to the factory, claiming that plans for a new grand prix car had been stolen and sold to a rival. The brouhaha hit the press and suspicion immediately fell on Ferrari’s nemesis, Maserati. Company president Adolfo Orsi called his lawyers, and Enzo was compelled to appear and sign a witnessed statement saying Maserati was not a suspect. As with so many of Ferrari’s little opera buffas, the controversy evaporated as quickly as it erupted.

In response to some perceived slight or to gain some small advantage, Enzo threatened to quit racing entirely so many times that journalists lost count. In 1953, he announced that he was retiring and closing the factory “for delicate personal reasons,” adding that “racing no longer interests me.” That September, Enzo amended his list of unbearable injuries to include the supposed theft of the blueprints. By December, the press reported Ferrari’s plans to continue into 1954. End scene.

And so it went; the Royal Automobile Club of Belgium canceled the 1957 grand prix at Spa because Ferrari refused to come unless the starters’ fees were increased. By then, wrote one reporter, staging a race without Ferrari was like staging Hamlet without the prince. In 1960, Ferrari pulled out of Sebring because of a dispute over the fuel sponsor (the cars were instead sent to Chinetti, who campaigned them under the North American Racing Team—NART—banner). In 1976, having lost an appeal over two contested grands prix, Enzo again said Ferrari was done with Formula 1.

“Withdrawals and threats of withdrawal used to be a regular feature of Ferrari’s end-of-season press conferences,” observed Eric Dymock, for many years the racing correspondent for Britain’s The Guardian newspaper, in a 1976 column. “For some reason or another, the 78-year-old autocrat, who has been connected with motor racing for nearly 60 years, took the huff over something and said his beautiful cars would never run again. Always he changed his mind.”

Experts seem to agree that Enzo sold road cars to pay for his racing mania. And that he scorned his customers, the dandies and poseurs and idle rich who groveled for his attention and threw reckless sums at him for cars. You can just imagine some of the characters who bought a Ferrari in the 1950s, when European cities still showed the scars of war and there were shortages of everything. One had to be a particular sort to want to flash wealth in that environment. In the 1960s and ’70s, their kids came back for their own cars, putting Enzo in a unique position to observe a particular kind of generational human folly.

But the tycoons and the toffs couldn’t help themselves; the exquisite driveway jewelry assembled behind the famous red gate on Via Abetone in Maranello set hearts aflame across all classes and nationalities. With Pininfarina’s growing involvement beginning in the early 1950s, Ferraris developed a more familial look in an expanding product catalog that was slowly becoming more organized, planned, and marketed. The factory’s output rose from dozens in the 1940s to hundreds in the 1950s to thousands in the 1960s. Enzo’s hidebound allegiance to solid axles, drum brakes, wire wheels, and front-engine configurations left him open to competitors, but nobody who ever bought a Ferrari was asked why. It remains a blue-chip purchase to this day.

Enzo surely had his eccentricities, but it’s hard to judge a man whose life was so equally blessed and cursed. He was at his son’s bedside in June 1956 when the 24-year-old, long suffering the slow erosion of muscular dystrophy, said, “Dad, it’s over,” and slipped into a coma and died. “I have lost my son,” Enzo wrote in a journal he kept of Dino’s illness, “and I have found nothing but tears.”

It was a ghastly period for Enzo and the Scuderia. Alberto Ascari had been killed in 1955 while he was taking a few quick practice laps at Monza in teammate Eugenio Castellotti’s 750 Sport. Castellotti himself died at Modena in March 1957. Luigi Musso and Peter Collins were both killed the following year at the French and German grands prix, respectively. And Phil Hill’s 1961 world championship–sealing win at Monza was clouded by the fatal crash of the popular and affable Count Wolfgang von Trips, which also massacred 15 spectators.

But it was the disaster at the 1957 Mille Miglia that was to haunt Ferrari for years. Alfonso de Portago, the handsome, athletic, and fabulously wealthy son of an Irish heiress and a Spanish count, was the sort of aristocratic playboy whom Ferrari derided and distrusted. Enzo always claimed to not have favorites, refusing to rank his drivers as other teams did. But he took the best shine to poor, up-from-their-bootstraps gunners such as John Surtees, whom he affectionately called “Giovanni,” and Gilles Villeneuve.

However, the 11th Marquess of Portago could drive, having earned his chops competing in the Carrera Panamericana and winning the Tour de France Automobile as well as the Nassau Governor’s Cup. Though Portago was infamously hard on his equipment, Ferrari assigned him as a last-minute substitute to one of the factory’s state-of-the-art 335 S roadsters. Enzo then turned the screws. He pointed out to the 28-year-old Portago that the Scuderia’s more experienced drivers, Piero Taruffi and Olivier Gendebien, had been given less powerful cars. Enzo then sniffed to Portago that it didn’t matter, that they would probably beat him anyway. Such were the standard mind games at Ferrari.

Near the end of the Mille, Portago’s 390-hp, 4.0-liter V-12 rocketed him and co-driver Ed Nelson, an American bobsled racer along for the ride as part of Portago’s clique of hangers-on, to 180 mph on the long straights across the Po Plain toward the Mille’s finish in Brescia. At the final rainy fuel stop in Mantua, Portago was running fourth behind both Gendebien and Taruffi, but he was told that the leaders were having mechanical trouble and that he was closing on Gendebien. Portago was offered a fresh set of Englebert tires to replace his badly worn skins, but he refused, taking a swig of orangeade and roaring off in haste toward Brescia.

Some 17 miles up the road, the slimy and battered Ferrari shrieked toward the village of Guidizzolo at around 130 mph. A front tire exploded. The car jinked left, clobbered a stone kilometer marker, and spun violently into a ditch, emerging 15 feet in the air as a pinwheeling, shrapnel-spraying buzz saw of death. It sailed over one line of spectators, hit the road, tumbled, and plunged into the crowd. Portago and his co-driver were killed instantly, as were nine bystanders, five of them children. The mayhem was so grisly that police had trouble identifying the bodies.

Italy erupted in rage. Protesters thronged the crash site and, later, the Ferrari factory, shouting, “Assassins! Criminals!” The conservative newspaper Il Tempo joined a media chorus denouncing the race, labeling it “an absurd fight between defenseless crowds and a small group of irresponsible men.” Enzo was brought up on murder charges, and the Vatican issued a statement calling him “a modernized Saturn devouring his own sons.” The Mille Miglia was finished but the legal wrangling lasted four years, until Enzo was dragged into court, where he broke down in tears after the first question from the prosecutor. He was soon acquitted, as it was estimated that up to a million people had lined a route with zero crowd control. The Scuderia soldiered on.

Italians obviously forgave Ferrari. The armies of tifosi swarmed to the tracks to cheer their nation’s gladiatorial heroes, even as Italian drivers appeared less and less frequently on Ferrari’s roster. It didn’t matter; if you drove for Ferrari, you were an Italian. Niki Lauda, who won two world championships with the Scuderia, wrote in his memoir, My Years With Ferrari, that after he flew his own plane to Italy in 1977 to end his stormy relationship with the team, the control tower at Bologna airport refused him clearance to leave. “You’ve got a delay of two hours,” Lauda recalled the tower radioing him. “No more priorities, no more VIP treatment. You left Ferrari, you bastard.”

As Enzo’s stature grew, so did his isolation. He never attended races, only the Saturday practice at nearby Monza. His sparse office was likened to a tomb, the walls bare except for a giant portrait of Dino looking down above a small shrine of flowers. His desk drawers were stuffed with trinkets to give away to the few visitors granted entry.

One such visitor in May 1963 was Ford Division assistant general manager Donald Frey, who had come to settle the question of Ford’s purchase of Ferrari. Enzo was content to let the road-car operation go for a relatively modest sum, but control of the racing team was a sticking point. Enzo began, “If I wish to enter cars at Indianapolis and you do not wish me to enter cars at Indianapolis, do we go or do we not go?” Frey’s immediate response was: “You do not go.” The meeting ended abruptly, with Enzo presenting Frey as a parting gift an autographed copy of My Terrible Joys.

Enzo regularly held court for his inner circle in the bar of the Hotel Real Fini in Modena, across the street from his house, then conducted his many liaisons in the rooms above. Family life was never simple or easy. His wife, Laura, whom he married in 1923, feuded endlessly with his widowed mother, Adalgisa, who lived with them until she died in 1965 at the age of 93. Laura’s increasing involvement in the factory was said to have contributed to a mass walkout of the top engineers in 1961. After that, she stepped back to a solitary life defined by a lost son and a wandering husband.

Over time, the question of the role of Piero, Enzo’s son by his longtime mistress Lina Lardi, became more pressing. Born in 1945, Piero began working at Ferrari in the early ’70s as Enzo’s personal translator, then moved into an assistant manager role of the F1 team. But it was awkward and not widely discussed until Laura died in 1978. Piero then adopted the Ferrari name and, after Enzo died, inherited his 10 percent share of the company along with a vice-chairman title.

The irony of Enzo Ferrari is that this famously unemotional man, who lived a virtual hermit’s existence in his later years when his dynasty was at its peak, evoked the greatest passion in everyone around him. “He was,” concluded Brock Yates, “exactly what he repeatedly said he was: an agitator of men.” The company bearing his name maintains no resemblance to the one Enzo left behind when he was laid to rest in the family crypt in San Cataldo. Years of modernizing by successors, especially Luca di Montezemolo, under the supervision of Fiat produced a publicly traded and thoroughly advanced engineering and marketing machine that Enzo would not recognize.

But there, on the next F1 grid, will be two blood-red Ferraris bearing the black Cavallino Rampante, the Scuderia showing up as it has for over seven decades to write history one lap at a time. Ferrari the man and Ferrari the company remain as inseparable today as they were when Enzo was alive. And as we all know, you can’t stage Hamlet without the prince.

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Enzo was a very driven and focused man.

He was not always poor but there were some very lean times as he forged what he wanted.

He was a motivated racer and competitor be it on track or in business. People to him often were the weak spot in business.

He really did have a heart. We see that with Dino as he never did recover from the loss.

Also while he did not mourn many drivers he did respect and loved Gilles Villeneuve to which he put a statue as a shrine to the very talented driver who in Enzo’s eyes gave 120% all the time. He also never blamed the car.

Was Enzo an easy man to be around no and most drive goal objective people are not. But like a true artist he left us with masterpieces we still treasure.

I just was in a F40 Enzo’s last car. This car was exactly what a Ferrari was to him. It was fast, light and had one reason to be. Just be fast.

His cars may have been great, but the man himself sounds like a “stronzo”.

In Which we worship a-holes this Christmas.

He is a complicated man, his story is very complicated. He gave the world some amazing cars. What the world thinks of him and his cars is now legend. Legends usually don’t resemble the actual people they are about. I do wonder what his life would have been if Dino had not passed away.

Your comment is awaiting moderation. – Arrrggghhhh!!!! Stupid system.

I think the title may be a little too broad; there’s definitely been some empires forged by the squeamish. Howard Hughes as a germaphobe comes quickly to mind. Some insecure rulers (ancient and more modern) seem like they may have been the “squeamish” types ha (“Let’s invade England and quickly setup armed forts because they’re not going to like us” – Some Roman dude and some Norman dude). The dirty peasants seemed to have made the aristocracy squeamish, more than once. Some of the food industry giants might have been on the squeamish side; I don’t get the impression they were all forceful business people.

On the flip side, I’ve seen some mid-level managers fall from graces for their lack of empathy/squeamishness. Confidence doesn’t always work out.

I saw the movie today. It was about what I was expecting.

This was limited look at Enzo in 1957. It only shows him fighting for his company and dealing with a distant wife and business partner and his second family while Morning for his first son.

When watching this movie you really need to keep in mind the Italian culture. Hard work, Catholic, in post war years and how relationship there can be very different. Not justifying anything but it was a different time and place and things just go differently in other cultures in the past.

Ferrari was a very driven man, yes he could be cold but the movie tried to show why he was like he was. We could debate the man but he was who he was and that is it.

The cars looked good, the crashes a bit computer generated like.

Scenery was spectacular.

Do not go with the intent of a feel good happy movie. It is about struggle and death.

I did wish they had more factory scenes and more with the cars. But by far this was a good movie.

I still rate Grand Prix as the best racing movie of all time. To be fair it may always be as you could never make a movie like that today.

But I would rate this in second tied with Rush. Rush had better action scenes with the real cars but Ferrari a much better story.

Ferrari vs Ford #4 as it is very entertaining but not exactly historically accurate.

#5 Stroker Ace just for fun and it was more like the real NASCAR than Days of Thunder. You would know what mean if you recall the JD Stacy era.

I do recommend to see this. I will add the Blu-ray later.

I could see a sequel to this as they could do a different era of his life.

It is very difficult to understand and appreciate the life of someone who witnessed two World Wars and a Depression through the lens of an Italian citizen. To this day, on its best days, the country seems to always be on the brink of chaos. Add in the post-war rebuilding and scrambling to survive, and nothing about his way of living and treating the people around him surprises me. As a DiMarco (Sicily), and an Ipolito (Naples), trust me when I say “It’s an Italian thing, you wouldn’t understand”

While not Italian I grew up around a Sicilian family.

Great people and great food but very different in how communicated and lived at time.

While still a very wealthy family my buddies mom dressed like she did in the old country with no flash. Now going out to dinner was something else.

His father loved to set up espresso for others that could have been used for battery acid. He loved to watch people trying to remain polite. He was a psychologist on top of that.

Communication was mostly yelling in Italian.

My buddy spent his summers in the old country with his grand parents. His experiences there were handed down to me and I ,earned much.

We hear in America are generations from our heritage. My people landed in 1650. My buddies 1950. He did not get the watered down version.

That is how you need to view this movie. Understanding Italy, their laws, their Culture to an extent and a bit of the Catholic faith in Italy at that time.

You have to remember the two most important people were Enzo and the Pope.

Even today at Monza if the Ferraris go out of the race at the start the massive crowd leaves.

It is just a different culture.

“”Vatican issued a statement calling him “a modernized Saturn devouring his own sons.””

It wasn’t the Vatican that issued that statement. It was the very conservative Vatican newspaper ‘Il Tempo’.

The Holy See didn’t control what is written in this daily newspaper.