Media | Articles

How a band of motorhead execs hatched the Dodge Viper

Now and again, lightning strikes the Motor City. These rogue bursts of energy once nudged Stevie Wonder and Aretha Franklin to R&B magic, and they still drive the occasional auto icon down an assembly line. Heavenly magic is how the ’32 Ford, the ’55 Chevy, and the ’65 Mustang came to be. In 1988, one of these lightning bolts moved Bob Lutz to conceive the Viper.

We’re here to celebrate the super snake’s 30th birthday by revisiting its life and times, spanning 25 model years. Though the wily serpent has slithered out of Dodge showrooms, its ardent admirers aren’t about to let it rest.

Legend has it that Bob Lutz was inspired to build the Viper by driving his Autokraft Mk IV Cobra replica. Carroll Shelby, the original Cobra’s progenitor, frequently reminded Lutz that his rustic roadster formula deserved a reboot. Following stints at GM, BMW, and Ford, Lutz joined Chrysler in 1986 as the company’s product guru. His boss, Lee Iacocca, was in the thick of a buying spree, adding AMC, Jeep, Lamborghini, and later Maserati to the fold. It was Lutz’s job to make this FrankenMotors walk and talk.

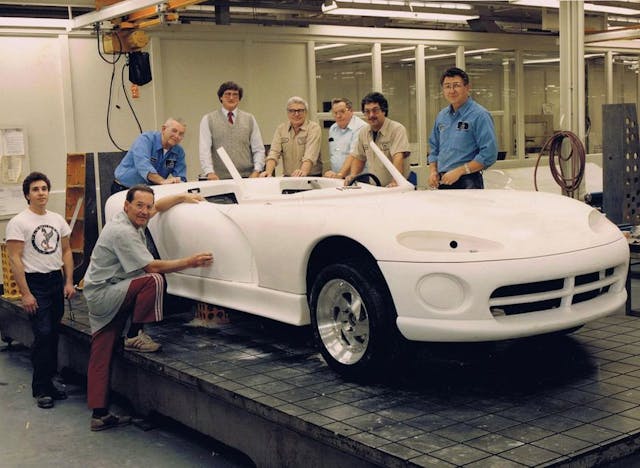

A hallway encounter between Lutz and design director Tom Gale set the “what if” stage. Bored with the K-car and its many derivatives, and impatiently anticipating the arrival of the cab-forward LH sedans (Chrysler Concorde, Dodge Intrepid, etc.), Lutz suggested that a revived Cobra could be a lightning bolt to energize the troops and signal to the automotive world that Chrysler had turned the K-car page. Like a school kid splitting for recess, Gale hustled back to his design studio to massage the clay.

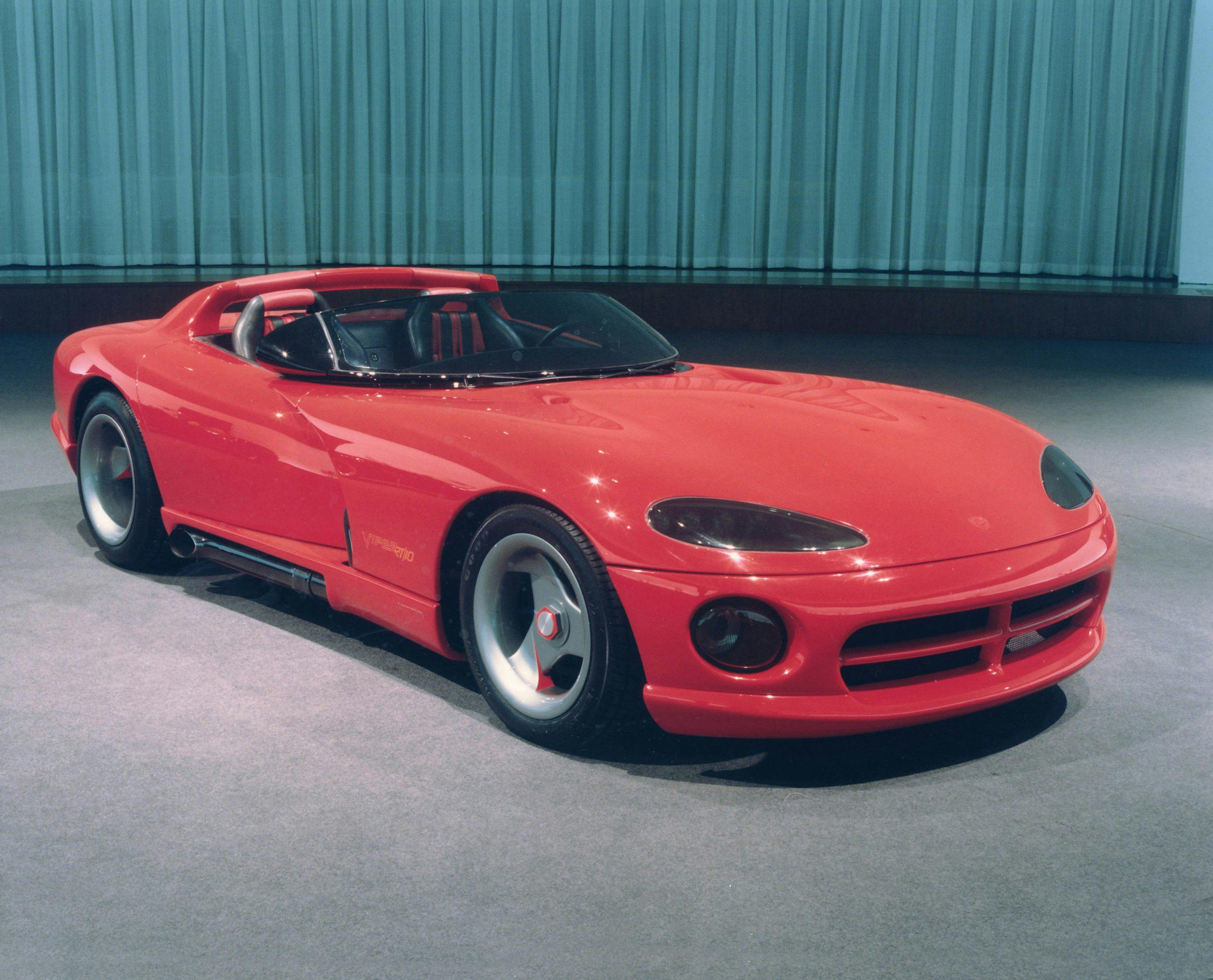

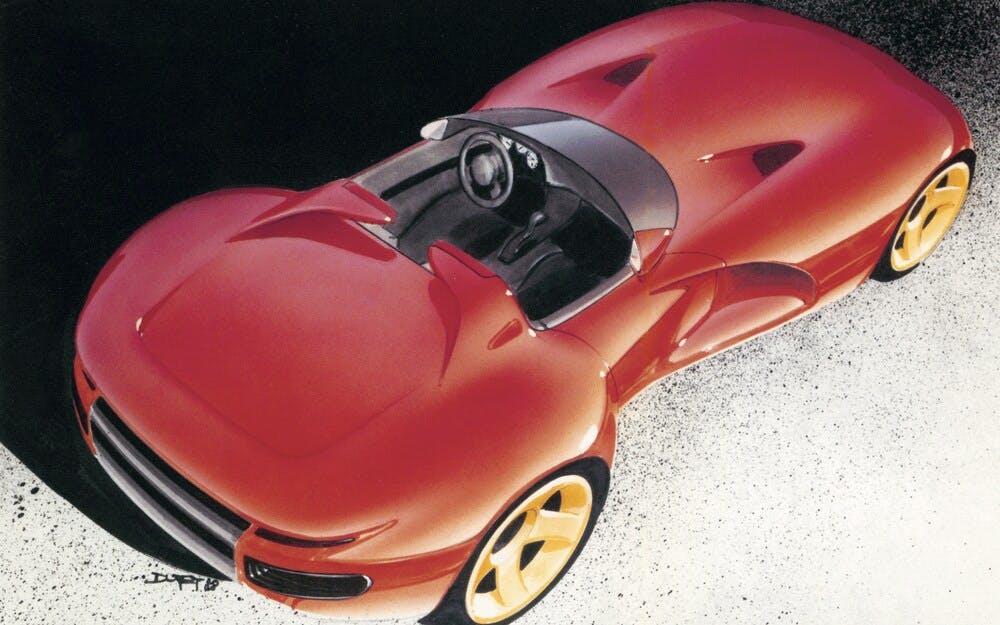

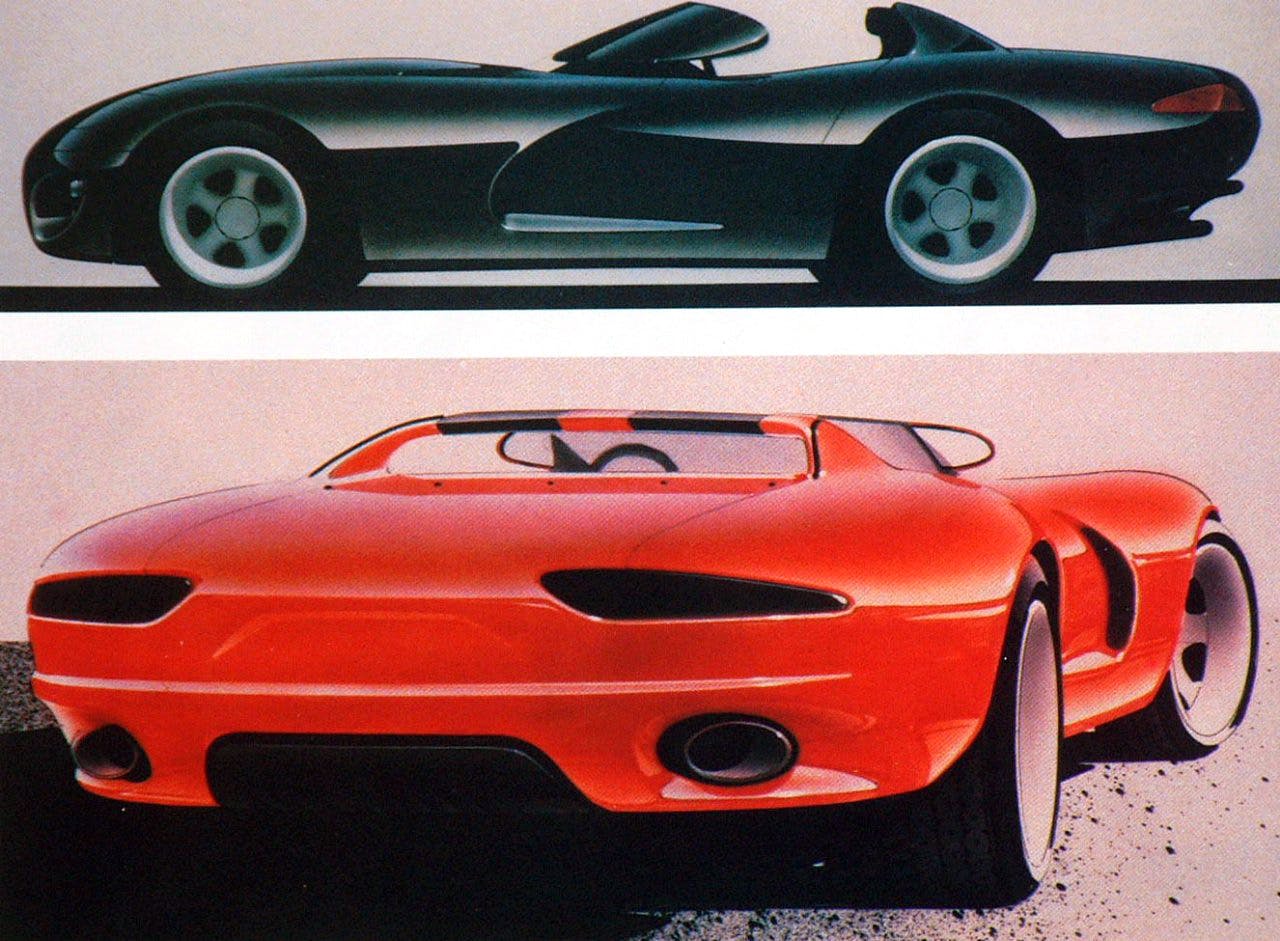

Gale’s first creation perplexed Lutz because it was more reminiscent of Jaguar’s low, shapely E-Type than AC’s simpler, blunter Ace, the forefather of the Cobra. The voluptuous bodywork was accented by a low windscreen integrated with the mirrors. Exhaust header pipes elbowed out of fender vents. Gale’s inspiration was unspoiled by side windows, door handles, or the targa bar that would later rise out of the deck surface. It was surely more than Lutz had expected.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The auto journos who witnessed Gale whisk the wraps off that clay model were shocked to their boxers. Its Viper name paid homage to the Cobra while confirming Dodge’s predatory intent. A barely running mockup was quickly constructed for a public debut at the 1989 Detroit auto show. Roush Engineering brazed two additional cylinders onto a Chrysler V-8, fabrication specialists Metalcrafters converted Gale’s clay exterior to sheet steel, and hot-rodder Boyd Coddington concocted a tubular space frame to support everything. The V-10 rattling the rafters moved showgoers to reach for their wallets to post a deposit. At the subsequent Chicago and Los Angeles shows, the Viper was again lauded as the most exciting Detroit development since the Corvette. Scores of newspapers and magazines splashed red ink celebrating the super snake’s arrival.

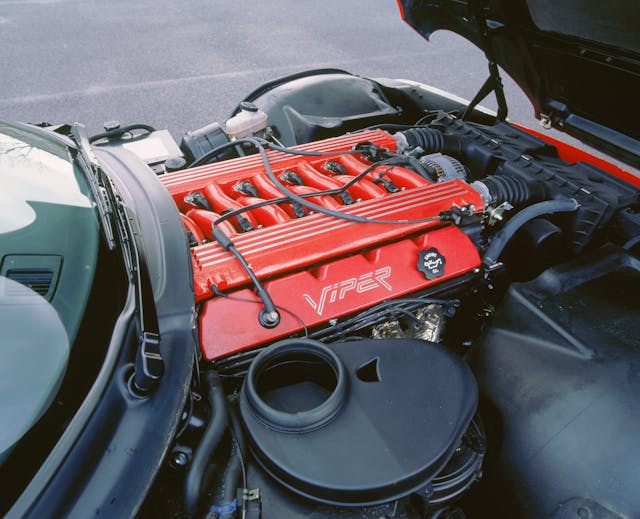

Why a V-10?

By 1988, Chrysler’s Hemi V-8 was ancient history, and a V-12 was too sophisticated for this malcontent. A V-10, created by tacking two cylinders onto the company’s 5.9-liter V-8, made perfect sense for Chrysler’s nonsensical sports car.

This was hardly the auto world’s first V-10. Audi, BMW, Lamborghini, and Porsche have all used them at various points, and Honda won Formula 1 races with such engines. Chrysler conveniently had a macho V-10 under development for Dodge Ram pickups when the Viper was conceived.

The one reason not to stretch a V-8 into a V-10 is that the V-8’s even firing intervals are lost. A cylinder fires every 90 degrees of crank rotation in a V-8, but adding two more cylinders results in firing intervals that alternate between 54 and 90 degrees. The syncopation moved one critic to liken Viper’s exhaust note to an angry UPS truck.

One lucky stroke was that Lamborghini, by then a Chrysler subsidiary, was available to help refine the Viper’s V-10. The brilliant Mauro Forghieri—who had recently moved from Ferrari to Lamborghini—guided the design of an aluminum block fitted with iron cylinder liners. His aluminum heads topped with magnesium valve covers had efficient combustion chambers and porting. The crankshaft and connecting rods were tough forged steel. The cast-iron truck V-10 that followed the Viper by two years never enjoyed such nurturing.

At birth, the 8.0-liter Viper V-10 produced a healthy 400 horsepower at 5200 rpm and 465 lb-ft of torque at 4000 rpm. During the four generations that followed, it grew to 8.4 liters and rose to a stout 645 horsepower at a rousing 6200 rpm and a meaty 600 lb-ft of torque at 5000 rpm. Of course, competition versions were even more potent.

Sequential electronic fuel injection, long intake runners, and tubular exhaust headers were instrumental in fattening the Viper engine’s output curves. While only two valves per cylinder operated by pushrods and rocker arms now seems mundane, Chrysler engineers cleverly implemented variable valve timing for this V-10’s fourth generation.

It was achieved by means of an unusual cam-within-a-cam arrangement, developed by German suppliers Mahle and Mechadyne. Their design uses two concentric shafts, a solid shaft inserted into a hollow one. During assembly, all 20 cam lobes for the engine and the six support journals for the shaft are installed onto the outer tube. The 10 exhaust lobes and the support journals are locked precisely in place with a press fit. The other 10 lobes for the intake fit loosely on the tube so they can move. They are secured in place by pins extending to the inner shaft. An electronically controlled phaser device, basically rotary vanes pushed by oil pressure, turns the inner assembly with up to 36 degrees of timing difference possible between the inner intake camshaft and the outer exhaust camshaft. Retarding exhaust valve timing at low rpm yields a smooth idle and low emissions. Advancing the exhaust timing at high rpm greatly enhances peak power and torque. To date, the Viper V-10 is the only engine in the world to employ this clever approach to variable valve timing.

Viper’s skunkworks

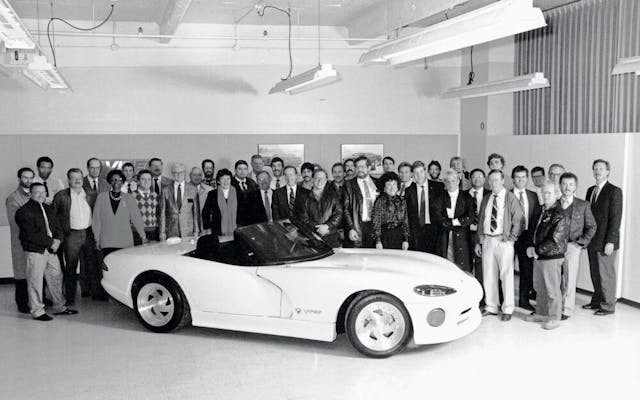

To study production feasibility, the seminal show car was handed over to an engineering team. Lutz specified three ground rules: a $50 million budget, a 36-month deadline to complete the effort in time for a 1992 Detroit auto show debut, and no shortcuts that would aggravate Chrysler management.

Roy Sjoberg, who joined Chrysler in 1985 after serving as Corvette godfather Zora Arkus-Duntov’s right-hand man, was appointed Viper’s chief engineer. He began by inviting a few dozen race-bred Chrysler engineers to a recruiting meeting. When word shot through the ranks at the speed of light, 300 showed up to offer their services.

Sjoberg selected 85 engineers, designers, and mechanics, many of whom had pro rally, Team Shelby road racing, or amateur track experience. He favored racers because he believed they could be trusted to work their butts off for long hours and modest pay. Sjoberg was inspired by Lockheed Martin’s Kelly Johnson, who developed the P-38 Lightning and U-2 spy plane in an agile organization known as the Skunk Works.

Sjoberg’s own skunkworks tapped Chrysler’s deep resources without getting mired in bureaucracy. Every engineer was authorized to make decisions on the fly. Members were instructed to act as if they had mortgaged their homes to underwrite this entrepreneurial enterprise. Chassis manager Pete Gladysz, who had headed Team Shelby’s SCCA racing program, explains: “Many of us had already worked together seven or eight years. We knew what the next guy needed and how he operates. You could hand such an associate a task and never worry about it being completed.”

Two mules were built with a $50,000 retail price in mind. The first one was powered by a V-8, the second by a cobbled-up V-10. Though the company had no experience manufacturing composite body panels, a craftsman appropriately nicknamed “Bondo” splashed fiberglass parts off Gale’s clay model. Upon driving the first prototype in December 1989, Lutz decreed, “You know what? You’ve got it!”

Iacocca’s turn at the wheel came less than a year later, in the second prototype. Upon completing a quick drive, he seconded Lutz’s motion, asking, “So, what are you waiting for?”

Driving toward the assembly line

Naturally, there were potholes in the road ahead. Getrag, initially tapped to develop the Viper’s six-speed transmission, couldn’t grasp how abusive American drivers could be burning rubber and slamming power shifts. Borg-Warner quickly stepped in to develop a gearbox with two overdrive ratios and a mechanism that forced first-to-fourth shifting during gentle driving to boost gas mileage. After a shootout between Goodyear and Michelin tipped the balance strongly in favor of the French brand, Chrysler’s purchasing authorities said no to using a “foreign” supplier. However, an expeditious phone call from Lutz resolved that issue.

In 1991, when the UAW objected to Chrysler’s use of a Japanese-built Dodge Stealth to pace the Indy 500, a preproduction Viper served as pinch hitter with Carroll Shelby at the wheel. That fall, scribes were treated to a scintillating week of Southern California preview driving. In addition to a trip through the Angeles National Forest, there was hot-lapping at Willow Springs Raceway followed by a freeway run south, during which California Highway Patrol officers stopped a few of the preproduction Vipers for close scrutiny. Phil Hill hosted an epic feast at his Marina del Rey restoration shop attended by several American Sports Car Heritage club members, including Carroll Shelby, Dan Gurney, Zora Arkus-Duntov, George Follmer, Sam Posey, and Parnelli Jones.

A key Viper mission was popping the Corvette’s bubble whenever possible. The timing was perfect to challenge the 1991 ZR-1 Corvette powered by a Lotus-designed DOHC V-8. The Viper’s 400 horses compared nicely with the Corvette’s 375, as did the Dodge’s $50,000 base price versus the Corvette’s $64,000 sticker. Car and Driver tests spotted the Viper a few tenths quicker to 60, while the ZR-1 won the quarter-mile race by two-tenths and 2 mph. From that confrontation onward, the Viper frequently served as the foil keeping Corvette engineers busy between coffee breaks.

Production of the Viper RT/10 commenced at Chrysler’s New Mack Avenue plant in Detroit in January 1992. The 150 or so workers initially built three cars per day, with a target first-year volume of 200–400 cars. True to the Viper’s rustic persona, the top was canvas material stretched between the windshield header and the targa bar. Side curtains were vinyl assemblies that plugged into place. Since there were no door handles, access to the cockpit was via inside latch releases. No options for air conditioning, airbags, antilock brakes, or automatic transmission were available. Due to the weighty V-10 and the heavy suspension components, the curb weight was 3450 pounds, well above the engineering team’s perhaps overly ambitious hopes of 3000 pounds, but hardly an issue given the car’s horsepower.

The second-generation Viper arrived in 1996 with notable upgrades. Engine output, heat management, and the soundtrack were all improved by a new exhaust system that replaced the blistering side pipes with mufflers hung under the tail. Actual sliding-glass windows were provided along with a removable hard top. The performance got hotter due to the addition of 15 horsepower and the loss of 60 pounds via lighter suspension components. Racy center stripes were available as optional equipment.

The grander 1996 news was the stunning GTS coupe with standard airbags, air conditioning, power windows, and power door locks. That warranted another stint as Indy 500 pace car, this time with “Maximum” Bob Lutz at the wheel. Both the coupe and the RT/10 roadster enjoyed a boost to 450 horses thanks to more aggressive valve timing and more efficient exhaust manifolds. Anti-lock brakes were finally added in 2001.

A GTS-R concept car revealed in 2000 previewed the fresh bodywork arriving on the third-generation 2003 coupe and convertible, both of which wore an SRT-10 nameplate. Sharp edges and angled lines supplanted the previous zaftig surfaces. Now the soft top was a clever folding design with the forward section doing double duty as a tonneau cover in the down position.

Both the V-10 engine and the chassis were notably lighter. A larger bore upped the displacement to 8.3 liters (506 cubic inches) and hiked output to a hearty 500 horsepower (later, 510 horsepower). When funds were too tight to develop a new aluminum space frame then under consideration, parent Daimler exported that technology to Germany for use on the Mercedes-Benz SLS AMG gullwing sports car.

For the fourth-generation 2008 Viper, V-10 displacement was increased to 8.4 liters. New cylinder heads boasting larger valves and more efficient ports were fed by dual throttle bodies. Adding variable valve timing enabled more aggressive cam timing, which boosted the horsepower to 600. An improved Tremec-built gearbox brought stronger synchronizers on all six forward gears, while a new speed-sensing limited-slip differential aided launch traction. To accommodate new Michelin Pilot Sport 2 tires, the chassis was retuned with spring-rate, antiroll bar, and damper revisions. A more modern electrical system improved engine cooling, throttle control, and fuel delivery. In spite of these fruitful upgrades, Dodge’s vice president and CEO Ralph Gilles announced that Viper production would cease in summer 2010, a victim (temporarily, as it turned out) of Chrysler’s 2009 bankruptcy.

Contradicting that edict, faithful owners and Dodge dealers were shown a fifth-generation 2013 Viper prototype in fall 2010, after Chrysler had begun merging with Italy’s Fiat. The public was taken with that car’s remarkable performance stats at the spring 2012 New York auto show: 640 horses, 0–60 mph in 3.5 seconds, and a 206-mph top speed. Larger Brembo brakes with ABS, traction and stability controls, and Pirelli P Zero tires brought improved braking and handling. The cockpit featured an electronic instrument cluster, a virtuoso Harman/Kardon sound system, and improved seating.

Unfortunately, when the fifth-gen Viper finally appeared in 2013, sales were lower than hoped for the Conner Avenue-built supercar, the result of base prices hiked to $100,000–$140,000. A desperate $15,000 price cut came with the 2014 model year. Chrysler finally pulled the plug in 2017 after a total of 31,069 Vipers had been sold globally.

Why the Viper died

Three years into the fifth-generation Viper’s five-year run, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles chairman Sergio Marchionne acknowledged, “The economics of the Dodge Viper’s exclusive architecture don’t add up to me.” What he didn’t mention was the major cost of meeting future side-impact collision standards.

The first year of any new model is often its best, but only 591 cars were sold the year the expensive fifth-gen Viper arrived for the 2013 model year. The later price cut sparked interest, but it didn’t stop average annual sales for that generation from dipping below 650 cars.

After the last Viper left the assembly line in August 2017, Lutz explained: “The Viper ran out of good reasons to live. The original premise was ‘more power and speed than anyone else.’ But the Viper was, in recent years, trumped by the Corvette Z06 and ZR1—and even in its own family by the Hellcats.”

Gilles, the fifth-gen Viper’s architect and now Stellantis’ global head of design, is more succinct when explaining his hero’s demise: “It was time. The Dodge Viper was an American supercar cloaked in mystique and legend. There will never be another car like it.”

We can only hope that Gilles is mistaken.

neighbor worked @ MASCO-TECH. Brought a [first year] mule Viper home w/Mfgr plate. Dash signed by

Dick Landy. Believe signed @ St. Ignace show that year. Big power!! Color? Red, of course!