Media | Articles

Coachbuilding has survived, but not without modern challenges

Henry Ford introduced the rolling assembly line in 1913 and brought automobile ownership within reach of the masses. He also put in motion the eventual decline of coachbuilding, a trade that is thought to date back to the Romans and which produced some of the most spectacular automobiles of the 20th century. Coachbuilders delivered a few handmade bolides produced by irreplaceable craftsmen using ancient tools and techniques, while mass production harnessed unskilled labor and mechanized automation to deliver millions of identical vehicles at an affordable price. One form of production flourished while the other diminished until, in the postwar period, it was practiced by only a few specialized design houses—and most of those are gone today. But has coachbuilding died out completely?

No. Thanks to new technologies and materials, plus an innate aversion by people of means toward commonplace consumer goods, coachbuilding has never really gone away. Today, the art of coachbuilding fuses cues from traditional hot-rodding, new-car customization, and old-car restoration. No surprise: Many of the skills and techniques for those various disciplines overlap. What fans of hot rods, customized new cars, and restored classics all have in common is the desire to own a car that is completely singular and not made on an assembly line.

“There’s something magical about things that are made by hand, whether it’s a leather handbag or a boat or a piece of pottery or a car,” says Steve Moal, whose family has been in the coachbuilding business for more than a century and who runs Moal Coachbuilders in Oakland, California. “Handmade things are not plentiful these days.”

Moal’s customers tend to be looking for one-off vehicles that evoke the past but are not replicas. For example, in 2012, Moal completed the Gatto, a Ferrari-powered coupe built from scratch that conjures—but does not copy—the 1950s work of Italian masters such as Zagato, Touring, and Pininfarina. Another current project in Moal’s shop is a tube-frame, aluminum-bodied roadster with the powertrain from an Aston Martin DB4. The owners, rabid Aston collectors, “just wanted their own Aston Martin-ish car that was completely unique. Nobody is trying to fool anybody—it’s not a real Aston. They’re just trying to pick up the spirit of the period,” Moal tells us.

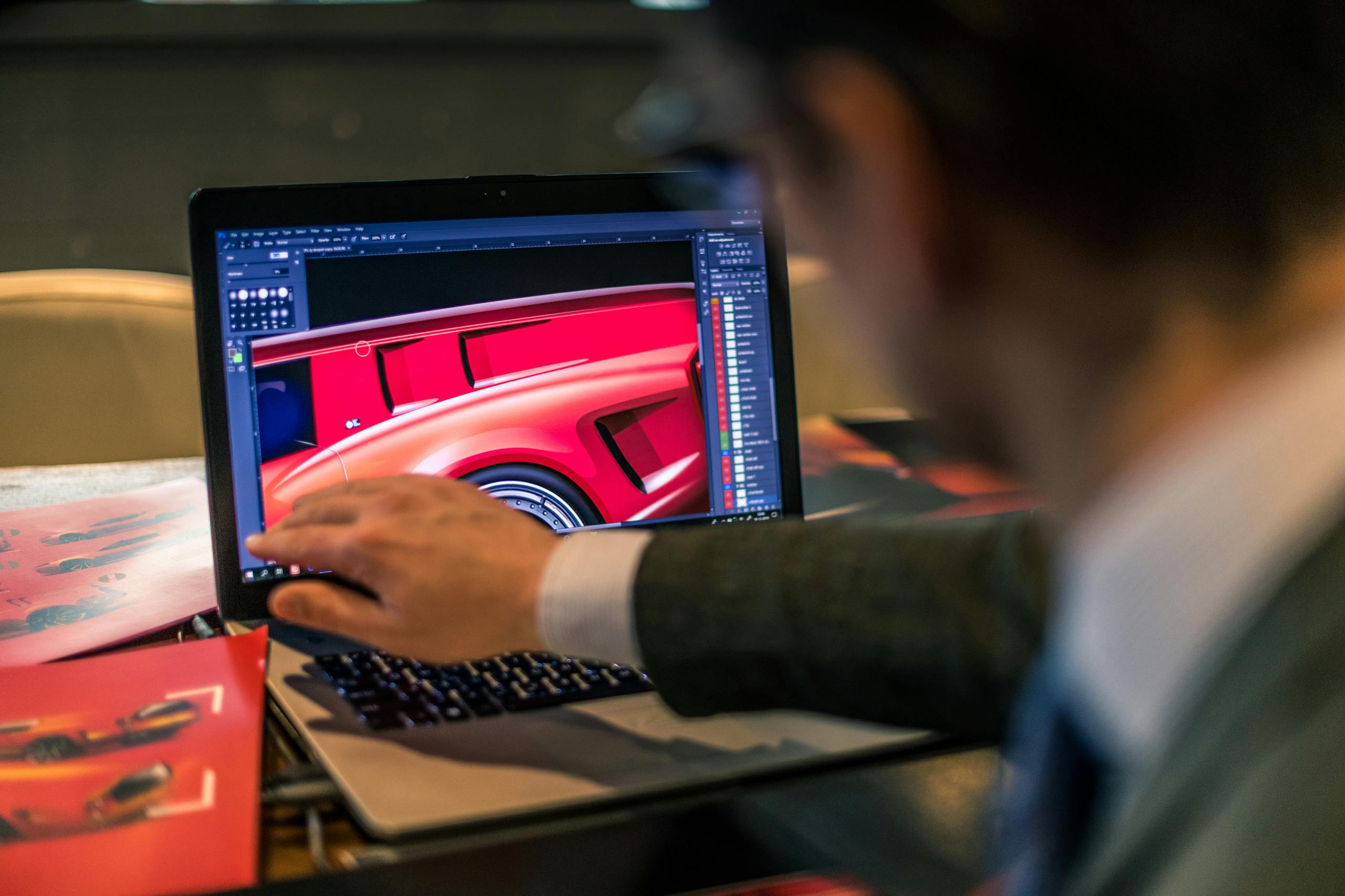

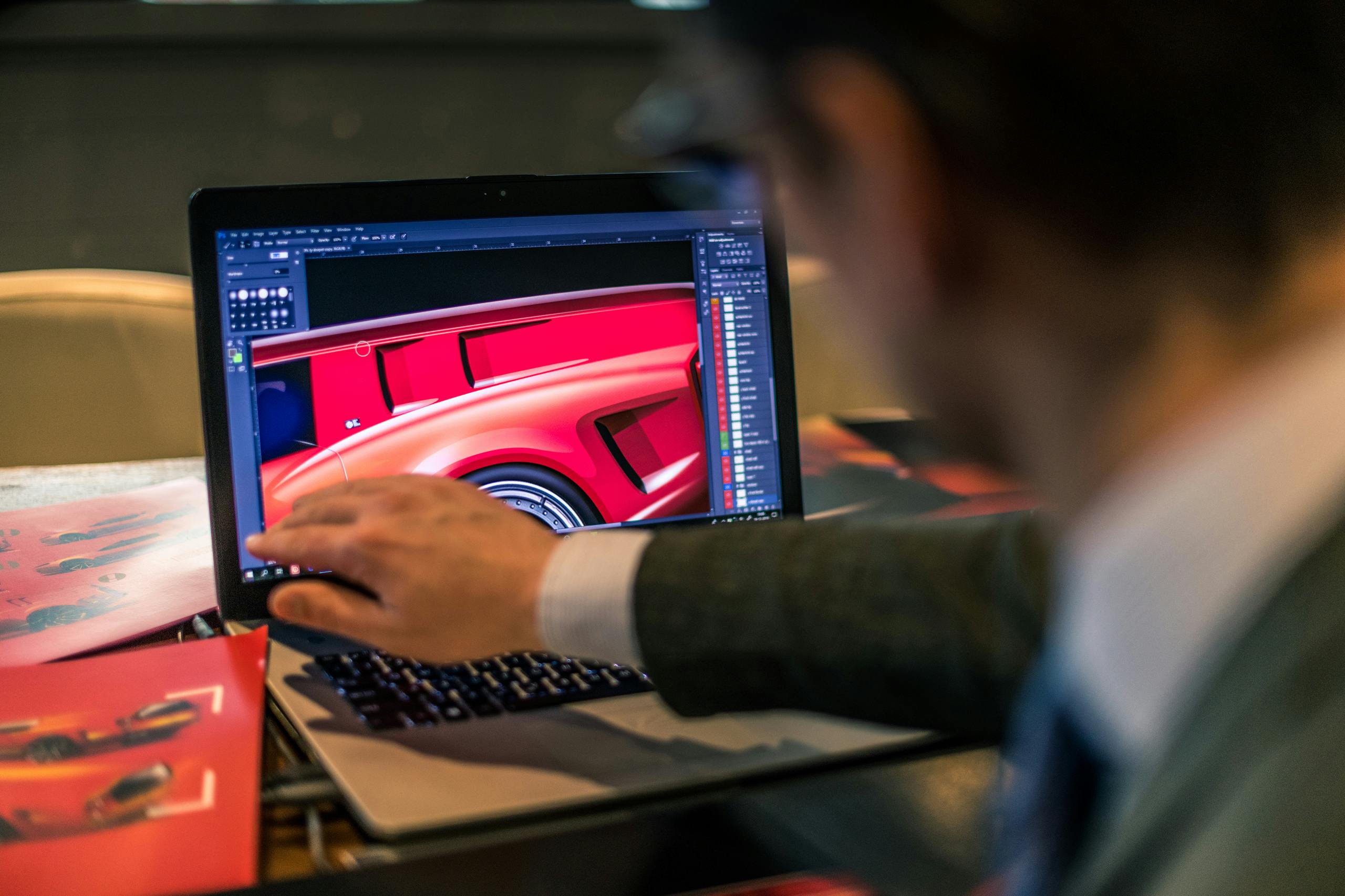

In another arena of modern coachbuilding, designers try to merge classic themes with 21st-century standards of technology, performance, and safety. “It will never be as free as the 1930s,” says freelance automobile designer Niels van Roij, who in 2016 was commissioned to create a one-off wagon version of a Tesla Model S, a project that led van Roij to make custom coachbuilding his full-time job. “We can’t possibly develop a whole car; it would never be at the level of an OEM. But there is still a lot we can do.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Van Roij’s “Breadvan Hommage” (pictured below) is just the sort of mad, nerdy fever dream that makes you both smile in amusement and nod in respect. You can’t believe somebody would be crazy enough to build a modern-day tribute to one of the oddest cars ever to turn a wheel in competition, and yet you love that somebody pulled it off. “In all honesty, the original car wasn’t a very good piece of design,” says van Roij of the original 1961 Ferrari 250 GT Breadvan. “They did it in a hurry.” But as an expression of one person’s obsession with Ferrari’s lesser-known history, the Breadvan Hommage is a perfect example of the unexpected directions that modern coachbuilding can take you.

Thanks to safety and emissions rules, you can’t walk into an automobile showroom, as you might in the industry’s golden years, and buy a naked chassis ready for a unique body from your favorite carrozzeria. But you can still commission a vehicle today that is entirely your own. That is, provided you’re willing to pay a lot, wait a long time, and make a million decisions about shapes and colors and materials.

“I once had a customer who squirted out a pack of Colman’s mustard and said, ‘Make that color,’” says Tim Gregorio, senior director of product experience for Singer Vehicle Design, which restores old Porsches with a highly contemporary flair. “What shocks me isn’t the number of people who go into this overwhelmed by the choices, but the number of people who know exactly what they want.”

Today’s coachbuilders stand on the shoulders of the giants who first recognized that the invention of the automobile could be a boon to the carriage-making industry that flourished at the end of the 19th century. Car buyers were no different from the buyers of horse-drawn barouches, landaus, and cabriolets, said Arthur F. Mulliner of the famous Mulliner coachbuilding family. Addressing the Institute of British Carriage Manufacturers in 1907, he said that “the purchaser of the motor carriage purchases because the carriage work meets his requirements or taste, and it is therefore the carriage work that sells the car.”

The interwar period of the 1920s and ’30s was the heyday of coachbuilding, mainly at the upper echelons of the market where the buyers of Duesenbergs, Bentleys, Bugattis, and other exotic marques could order bespoke bodies from separate firms. Their names echoed those of any fine clothier at the time: the Walter M. Murphy Co., J. Gurney Nutting & Co., Carrosserie Gangloff, and Figoni & Falaschi Carrossiers, among the many that hammered the metal that graces the cars that today populate the major concours. It’s said that the level of opulence (plus the simplicity of the engineering at the time) was such that some owners had both summer and winter bodies for the same car.

Social upheaval in the Depression and the subsequent world war ended many of these firms, while the auto industry that emerged from the era was leaner and more focused on volume through line production. Still, the coachwork industry thrived for a time, especially in Italy, where ancient metal-working skills were still nurtured and where design has always trumped most other considerations in manufactured goods. “It is in my country’s nature to have specialists,” Sergio Pininfarina once told a reporter. “Our people are artisans. We take pride in our work and perhaps we also know something about form and function.”

Through the 1950s and early ’60s, famous design houses such as Pininfarina, Bertone, Touring, Boano, and Zagato continued to sculpt fabulous creations for discerning buyers who craved exclusivity. However, the business was changing fundamentally. To survive, the coachbuilders turned from catering to individuals to catering to automakers, competing to build the high-profile, low-production models that larger companies were either too busy or too focused on volume to produce themselves. The business became less about individual taste and more about pleasing corporate clients and their committees of designers, engineers, and bean-counters. “I’ve known car builders from all over the world,” commented Nuccio Bertone to the author of a book about his company. “And every man jack of them had his own opinion.” (The only exception, Bertone noted, was Ferruccio Lamborghini. According to Bertone, “He said, ‘I’ll make the mechanical bits, you see to the body. The Bertones of this world don’t need my ideas.’”)

But the blazing meteor that took out most of these remaining firms was the increasing regulation that in the 1970s drastically drove up the costs of developing new cars. Over time, the industry responded through model consolidation, producing fewer specialty vehicles; in the 2000s, design work was pulled almost entirely in-house. Even Ferrari ended its nearly 70-year relationship with Pininfarina in 2017 when it cut the front-engine F12, the last production Ferrari to wear a Pininfarina badge. It was part of the decimation of the independent Italian coachbuilding industry. Pininfarina was purchased by India’s Mahindra Group and now lives on as a design consultancy. Bertone went bankrupt in 2014 and folded, its name sold to an architectural firm in Milan. Zagato has evaded death only by becoming an independent design house working on everything from commuter trains to agricultural harvesters while still producing the occasional dream car and rebodied Aston Martin.

Today, what is left of the coachbuilding trade is a tiny cottage industry largely dedicated to building retro cars from scratch or reshaping existing mass-production vehicles into one-off creations that express their owner’s personality and aesthetic. Commissioning one lands somewhere between ordering a tailored suit and building a custom house in terms of cost, personalization, and buyer involvement. Projects typically take from a year to 18 months (though Moal has done projects stretching to five years), they usually cost double but often triple the original purchase price of the car, and they require the designer and customer to practically get married. “The client needs to be willing to invest not just the funds but the time,” says van Roij, whose portfolio includes the design for a Rolls-Royce Wraith shooting brake called the Silver Spectre (seven will be made), and a modern two-door Range Rover dubbed the Adventum Coupe that evokes the configuration of the 1970s original.

“I visit the client at home to see their art, what their musical tastes are, and what’s in their garage,” says van Roij. “I know their wives, I know their children, I know the name of their dog.” In return for all this openness, he adds, the client gets back a car that expresses his or her individualism in a way no mass-produced car could ever do, no matter how the option boxes are checked at the dealership. When van Roij worked on converting the Tesla Model S into a wagon, for example, the factory green was abandoned, he says, for a green that was more vibrant and complimentary of the new shape—and which also came from the logo of the client’s company. “That’s what coachbuilding is about,” says van Roij. “The rest of the world sees a green car and [the owner] sees his company that he built.”

Similarly, the Breadvan Hommage completed last year expresses a reverence for Ferrari history while also taking liberties to produce a car with a more curated and harmonious shape than the original. That’s partly because van Roij isn’t interested in producing exact copies, and partly because the original, a used 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB modified by privateer racer Count Giovanni Volpi as an aerodynamic experiment, was not especially pretty, van Roij says. “They didn’t call it the Breadvan because they liked it.”

However, a Ferrari enthusiast in Germany was keen to create a car that evoked Volpi’s strange machine (born out of a spat that Volpi was having with Enzo Ferrari, who refused to sell Volpi a new GTO). Sketches were made, followed by an expensive full-size clay model—a step not many builders take but which van Roij insists upon for any commission as he believes it’s the best way to visualize and perfect the design before metal is cut. Certain hard points of the manual-transmission Ferrari 550 Maranello coupe on which the Hommage is based were preserved to retain the modern usability as well as to hold down costs. “If you change a door by 2 centimeters, it can cost $20,000. You have to change the glass, the rubber, all the sensors. The amount of engineering is huge.” The result shows a modern reshaping of the original’s numerous vents and ducts as well as a rethinking of its Kammback rear—though, in the end, after trying different rakes to the tail, van Roij and his customer agreed to adhere to the original’s perfectly vertical rear end. It’s the only part of the nuovo Breadvan that matches the 1961 car line for line.

The techniques used to make the Breadvan as well as most coachbuilt cars today are Old World—and painstaking. Steve Moal’s craftsmen work mainly in aluminum for its vintage appeal and light weight, but it’s a demanding metal that requires knowledge and experience to get right. “Where you put the seams is important, so it doesn’t fatigue and crack,” he says, adding that old-school oxyacetylene welding is employed because the finished weld is more malleable and less prone to cracking. “When you’re finished, it’s beautiful, but it isn’t always beautiful along the way.” Still, Moal’s clients tend to like some imperfections in their cars, the hammer marks and other evidence of handwork, at least underneath. “We have a sports car here that is finished in gloss black and it’s perfect, but we have not painted the inside panels, because the owner wants to see what I like to call the signature, or the fingerprints, of the craftsman.”

At Singer, which is based in Southern California and has delivered fewer than 160 cars over its 13 years of operation, the goal is to fully preserve the 1989–94 Porsche 911 (aka 964) that the company uses for donor cars but with a thoroughly contemporary updating in both performance and styling. Incoming cars go through a 4000-hour transformation in which they are stripped down to the bare metal, repaired from years of road use, altered as needed for new components (for example, the company replaces all of the factory hinges with milled aluminum ones of its own design) and to clean up unnecessary brackets and reshape less-than-lovely factory welds and edges. The car is then fitted with carbon-fiber body components before heading for paint and interior trim.

While more of a restoration shop than a coachbuilder, Singer nonetheless shows what is possible—as well as what is challenging—in using new materials such as carbon-fiber composite. Every exterior panel on a Singer project except for the doors is either remade in carbon fiber or skinned in carbon fiber, says Gregorio, the components sourced as a kit from a local aerospace supplier. The material has advantages in weight and durability but also requires new techniques. Unlike the aluminum and steel that skilled craftsmen shape with press brakes, English wheels, and hammers, carbon fiber is molded to its final form.

“You can’t shape it after the fact or just push it a bit to fit; you get what you get, which is why you need to maintain a very good relationship with your carbon supplier,” says Gregorio. A worker trying to achieve Singer’s tolerance goals of a half-millimeter can’t even grind carbon fiber if the piece is slightly oversized. “Once you grind it, you can’t put it back like you might tack a weld onto metal,” he says. “You approach it with a very light hand.”

During the month or so that the car spends in Singer’s body shop, the new body panels will go on and off the car six or seven times as the company’s technicians perfect the fit. Particularly nerve-racking is a carbon-fiber skin that is bonded to the factory’s original steel rear quarter panel, which can’t be replaced entirely with carbon because it’s a load-bearing part of the car’s monocoque shell. The huge composite piece that Singer applies stretches from the aft doorjamb to the rear bumper and is bonded with an adhesive that allows workers to adjust it for up to 30 minutes, though if it’s hot in the shop, that lessens the cure time. “You only get one shot at it,” says Gregorio. “If you have to remove it, it would require major surgery.”

Today, coachbuilders are hemmed in by constraints that would have been unimaginable to their early predecessors, ranging from new materials to regulatory prohibitions to trademark issues. In the past, Ferrari has attempted to use trademark protection to insulate its designs from modification or copying. And owners of the trademark for the modified 1967 Mustang known as “Eleanor” from the 2000 film, Gone in 60 Seconds, have sued to stop unlicensed copies.

Is it even legal to modify a current production car for your own purposes? Singer makes it very clear that they “restore” cars, not “build” them, the semantic dance done to keep the company free of legal entanglements. James Glickenhaus, the New York–area collector, racer, coachbuilding customer, and now full-time carmaker, notes that it is one thing to modify a one-off car for a private customer; quite another to make a business out of it. Basically, “you have to talk to your lawyer,” he cautions, adding that Ferrari allows customers to modify a new car and leave the Prancing Horse on it, but doesn’t allow any changes to the windshield or any of the side glass. The Maranello firm will bless factory-modified cars, as it did so often for the Sultan of Brunei, who was famous for his stable of bizarre, one-off Cavallinos, but the fee runs into the millions.

Glickenhaus started creating his own cars in 2006 when he built the Ferrari P4/5 as a tribute to his favorite 1960s-era prototype sports racers. “Having driven every type of exotic car of the past 50 years, I know a few things about them,” he says. The donor car was a brand-new Ferrari Enzo that was heavily modified, the design and fabrication work done by Pininfarina. The ultimate product was a stunning machine that looked both backward at the company’s racing history and also forward toward the future, but the price was equally dizzying. Just tooling up a set of bespoke tail-lights for the P4/5 that were DOT compliant cost $250,000, Glickenhaus says.

Since then, he has branched out with new designs for supercars, including the sexy mid-engine, three-seat, manual-transmission wedge called the SCG 004, as well as an off-road buggy called the Boot, a tribute to the Baja Boot that Steve McQueen raced in the Baja 1000 in 1969 (Glickenhaus owns the original). But Glickenhaus has moved beyond being a mere client or coachbuilder; he will make new cars from the ground up at his facilities in Danbury, Connecticut, and Pont-Saint-Martin, Italy, north of Turin.

Jumping from coachbuilding or resto-rodding to full-blown carmaker producing legally certified vehicles is not a move for the faint of heart. “To start a small car company, it’s $100 million to start,” says Glickenhaus, and “if you make a car nobody wants to buy, then you might as well take that money and sink it in the East River.” Still, he notes, a run of a few hundred cars (with the first deliveries of the 004 and Boot expected this year) should make the business profitable, assuming he’s gauged the market right.

Most people wanting a unique car do not want to be automakers. For them, hiring a coachbuilding firm to alter an existing car will be enough of an exposure to the stresses and challenges of carmaking. And for the effort, they will not only own a unique automobile, they will get to delve into that curious area where art and machinery merge. For the job of the coachbuilder, Nuccio Bertone once mused to a journalist, is “the realization of a dream which is present in us all but which only the artist has the ability to translate into concrete form.”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

I read your fine article on coach building and have long shared a love of antique automobiles. With all your knowledge of the industry I would like to inquire if you would know any company that will take a 4 door Bronco Sport and turn it into a 2 door ? I guess they would stretch the front doors 8 or so inches, move the pillar back and eliminate the rear doors ? I am a paraplegic and want a car I can drive like a normal driver.

If you can help I would greatly appreciate it, anyway Thanks for listening